Abstract

We estimate the impact of pension enrollment on mental well-being using China's New Rural Pension Scheme (NRPS), the largest existing pension program in the world. Since its launch in 2009, more than 400 million Chinese have enrolled in the NRPS. We first describe plausible pathways through which pension may affect mental health. We then use the national sample of China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) to examine the effect of pension enrollment on mental health, as measured by CES-D and self-reported depressive symptoms. To overcome the endogeneity of pension enrollment or of income change on mental health, we exploit geographic variation in pension program implementation. Results indicate modest to large reductions in depressive symptoms due to pension enrollment; this effect is more pronounced among individuals eligible to claim pension income, among populations with more financial constraints, and among those with worse baseline mental health. Our findings hold for a rich set of robustness checks and falsification tests.

Keywords: Pension enrollment, Pension income, Depression, Mental health, Older populations

JEL classification: H55, I18, I38, J14

1. Introduction

Many countries have recently adopted or reformed social pension programs to better support the needs of the elderly. Improved understanding of the income-health gradient may lead to the development of more effective pension programs as well as retirement policies.

Although the income-health gradient has long been an important topic of investigation, existing research is not conclusive. While early studies found a strong income-health gradient (Marmot, 1994), few incorporated a study design that would demonstrate a causal relationship (Marmot, 2002; Deaton, 2002). Findings also conflict. For instance, Snyder and Evans (2006) find that higher pension income leads to higher mortality, while others find that higher pension income leads to better health status (Case, 2001) and lower mortality (Jensen and Richter, 2004).

The literature on income-mental health gradient is more scant. This paper provides novel evidence on the causal impact of pension provision on mental well-being. Mental health is an important component of overall health status. Mental disorders are among the most common causes of low quality of life, disability and death (Byers et al., 2012) and account for a large share of lost disability-adjusted life years and therefore the overall global burden of disease (Collins et al., 2011). In addition, mental health plays an important role in maintaining physical health (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009). The rapid aging of the world population further raises the importance of improving mental health at older ages, because older adults have both high rates of mental illness (WHO, 2017) and among the highest suicide rates of all age groups (Case and Deaton, 2015; US CDC, 2016).

Credibly establishing a causal pathway between income and mental health has proven difficult. First, there is concern over reverse causality. If the gradient arises primarily because of causal pathways from mental health to income (i.e., good health leads to higher productivity and income), then strategies directly targeting health behavior may be most effective. If, on the other hand, the gradient arises primarily because higher income causes improvements in mental health, policies that make economic resources available may be most efficient in promoting mental health. Second, unobserved factors, such as genes or social trust, may affect both income and mental health, leading to biased estimates.

Although LMIC Populations have more than twice the rate of depressive symptoms, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders compared to their U.S. counterparts (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1999; Byers et al., 2010), the literature on the causal impact of income on mental health, especially in the elderly, has been limited to the developed country context (Golberstein, 2015). However, more than 80 percent of the world's 2 billion older individuals will be living in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) by 2050 (Suzman et al., 2015) and investment in mental illness prevention and treatment remains low in LMICs (Collins et al., 2011). This paper provides some of the first causal evidence of pension provision on mental health in the developing context.

In attempts to identify the causal impact of income on mental health, studies have used quasi-experimental study designs and examined the effects of a financial crisis (Friedman and Thomas, 2008), moving to higher living standards (Stillman et al., 2009), job displacement (Sullivan and Wachter, 2009), winning the Nobel Prize (Rablen and Oswald, 2008), lottery winning (Apouey and Clark, 2015), and receiving an inheritance (Kim and Ruhm, 2012). However, the mental health consequences of some of these events can be confounded by changes in other covariates unrelated to income per se. People who purchase lottery tickets may demonstrate quite different risk preferences than the general population, which may threaten the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, this causal interpretation also relies on the strong assumption that lottery success is not directly correlated with mental health. People who receive inheritance have presumably lost a loved one, which may also affect mental health, a potential violation of the exclusion restriction. Also important for policymakers, most studied shocks are in the form of a lump-sum transfer, which may affect mental health differently than an annuity, due to a violation of fungibility (Thaler, 1990).

To overcome these issues, a few studies explore exogenous changes in income, such as the German reunification for East Germans (Frijters et al., 2005), the New Jersey-Pennsylvania Negative Income Tax Experiment (Elesh and Lefcowitz, 1977), the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) in the U.S. (Evans and Garthwaite, 2014), the Child Benefit System in Canada (Milligan and Stabile, 2011), and the Social Security Notch (Golberstein, 2015). However, while some of the existing studies find positive causal linkages between income and mental health, many fail to find compelling evidence (Frijters et al., 2005; Adda et al., 2009; Stowasser et al., 2011), and a few even report small negative effects (e.g. Snyder and Evans, 2006).

In this paper, we consider the largest pension program in the world – China's New Rural Pension Scheme (hereafter NRPS). Our identification strategy relies on the fact that the program had a staggered rollout (2009–2012), with residents of some counties enjoying earlier eligibility and pension receipt. Government documents indicate counties were randomly chosen for earlier implementation (State Council of China, 2009), an assumption we test explicitly in this paper using a rich set of county-level variables.

We use the 2012 China Family Panel Studies (hereafter CFPS), which contains the 20-item full version of Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977). The CES-D is a comprehensive measure of mental health and enables us to measure changes in a continuous measure of mental health as well as dichotomous changes in depressive symptoms.

We construct two samples for our analysis: one consisting of older persons (ages 60 plus) who are eligible to claim pension benefits, and the other comprised of younger adults (ages 45–59) who are eligible to contribute to subsidized pension account, but do not yet receive pension payments. Our results suggest that pension enrollment generates modest to large improvements in mental health for the former group, but the latter group experiences no such benefit. These effects hold under a set of robustness checks, falsification tests, and IV estimations with individual fixed effects (IV-FE). We find the impact is unevenly distributed. Specifically, pension disproportionally improves mental health of those in relatively worse mental health status, and in the lower segment of socioeconomic status (measured by educational attainment and income).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides the institutional details of the NRPS. Section 3 discusses our conceptual framework for this analysis; Section 4 describes the data and the estimation strategy. Section 5 presents results. Finally, section 6 concludes the study and discusses policy implications.

2. China's new rural pension reform

Against the backdrop of rapid economic growth, increasing life expectancy and a declining fertility rate (following the introduction of the One-Child Policy in the 1970s) has led to an acceleration of demographic aging in China. However, prior to 2009, there was little formal social safety net for the rural elderly population. To provide a more robust system of old-age support, in 2009 China launched a pension program for rural residents. By 2012, the NRPS covered more than four hundred million rural residents, among whom almost ninety million were greater than 60 years of age. The NRPS benefit contains two components: a noncontributory (or basic) pension and an individual account (based on individual contributions with government matched subsidy). Both are paid to participants when they reach age 60. However, enrollees age 60 or above at NRPS rollout had no option for an individual account, limiting them to only receive the basic pension.

The basic pension financed solely by the government is available to all enrollees at age 60 (Chen et al., 2017a). While the NRPS was rolled out at the county level, the level of basic pension is set at the provincial level. Many provinces set 55 CNY (or around 9 USD) per month as the basic pension benefit, although a few wealthier provinces (e.g., Beijing, Tianjin) set the benefit at up to 360 CNY (or around 60 USD) per month. The government fully finances all basic pension benefits.

Regarding the individual (or contributory) account, according to the guidance released by the State Council of China, there are five categories of premiums for individual accounts: 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 CNY per year per person. While some provinces offer additional higher levels of individual premiums, a majority of participants choose to contribute 100 CNY per year per person, the lowest level of pension premium (Lei et al., 2013). The financing of the pension benefits comes in part from a government subsidy of 30 CNY per person per year for the first 100 CNY of individual premiums contributed to the individual account; there is a lower than proportional subsidy for additional individual premiums contributed.

At the time of the roll-out, the provisions for the individual account differed by age. Adults below age 45 at NRPS rollout must contribute to the individual account for at least 15 years to be eligible to receive benefits drawn from the individual account at age 60 (of course, they would be eligible for the basic pension conditional on making these contributions). Those age 45–59 at NRPS implementation may contribute for any (positive) length of time to be eligible for the individual account benefit.

Total pension benefits, including basic pension and a possible individual account, are approximately 15 percent of China's average earned income. Thus, the NRPS offers a modest payment compared to many other developing countries, such as South Africa (Lund, 2007).

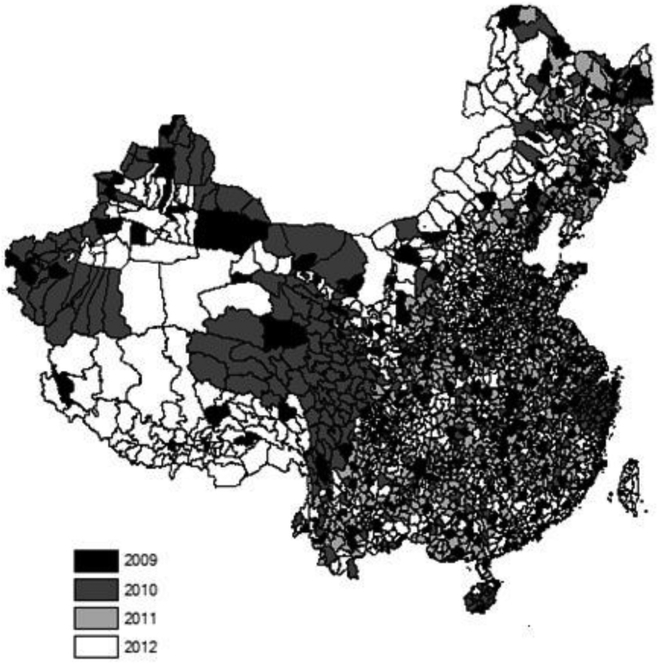

As previously noted, NRPS was rolled out gradually. According to the official document No. [2009]32 (State Council of China, 2009), the central government attempted to randomly select counties for pilot implementation without any written criteria. In our empirical testing, we look for evidence that county government self-selected into pilot implementation or its roll-out timing based on a rich set of observable characteristics and find none. As described in the official documents released by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, the first implementation group adopted in September 2009, and covered roughly 10 percent of counties; the second implementation started in August 2010, and increased the proportion of counties participating to 25 percent; the third group implemented since July 2011 with 60 percent of all counties covered. By the end of 2012, all counties had adopted the program. Fig. 1a indicates roll-out timing at the county level.

Fig. 1a.

Rollout of new rural pension scheme in China.

Notes: The NRPS was rolled out nationwide at the county level during 2009–2012.

The NRPS may demonstrate heterogeneous impacts due to large socioeconomic inequality. For example, pension payment accounts for more than half of the income per capita for a household in the lowest 10th income percentile in China (Cai et al., 2012). That older individuals typically earn much less than younger individuals also may lead the NRPS to generate a larger impact, especially in regions that are lagging behind in economic growth (Chen et al., 2017b).

3. Conceptual framework

The determinants of mental health are complicated, involving socioeconomic and physical environments at different stages of life (WHO, 2014). In our context, mental health has been found to be associated with socioeconomic status (e.g. marital status, education, income) and physical health (e.g. chronic disease) for the aging population in China (Lei et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014; Qin et al., 2018). Special attention should be paid to income as it not only affects mental health directly through investments in mental health but indirectly via other socioeconomic factors and physical health conditions. The Grossman model of health capital (1972a, 1972b) provides a conceptual basis for analyzing the relationship between income and mental health. The model makes a clear conceptual distinction between inputs in mental health production and mental health outcomes. Even if mental health inputs are normal goods, so that increases in income cause a rising quantity of input demanded, the net effect of increased income could be negative if income elasticity with respect to unhealthy goods (e.g. unhealthy behaviors and lifestyle) is sufficiently high.

It is worthwhile to think about channels through which pension may affect mental health investment and health outcomes and, in particular, which of these channels are likely to apply to the Chinese context studied here. Grossman's framework suggests that pension payments to the older cohort (those age 60 or greater) may affect mental health through at least three plausible channels: (i) changes to lifestyle factors, such as independent living, service consumption, leisure time, and connectedness with friends and communities; (ii) health investments, such as nutritional intake and medical treatment; and (iii) economic security leading to reduced financial stress.

First, elders who prefer to live independently and are able to do so due to increased income likely have better mental health through channel (i). This is in part because these individuals have a greater sense of self-actualization. The atomization of extended families may reduce family conflicts (The Economist, 2014). Recent studies on the NRPS show that pension results in older Chinese living more independently (Cheng et al., 2018), spending less time caring for grandchildren Chen et al., 2017b), and with children of older Chinese more likely to move out or even migrate away from the home county (Chen, 2017). Also relevant, prior work finds the NRPS is associated with the targeted age group hiring others to relieve arduous household chores resulting in increased leisure time (Chen, 2016). These changes in lifestyle are protective factors for mental well-being (Devoto et al., 2012). In this study, we do not find any evidence that pension benefits significantly increase the chance or size of financial support to children from pensioners, meaning that the concern over pension benefits spilling over to other generations can be mitigated.

Second, health care resources are often expensive in LMICs where individuals often rely on out-of-pocket funds to finance medical care. Through channel (ii), pension income may improve mental health via reducing the relative cost of inputs for health. The combination of widespread stigma regarding mental illness (Fung et al., 2007; Young and Ng, 2016), poor mental health literacy (Wong et al., 2012) and limited capacity to treat mental illness in China (The Economist, 2017) results in a low fraction (8%) of Chinese with mental illness being treated (Xiang et al., 2012). Therefore, we expect the health investment channel is mainly indirect, i.e. through better nutrients intake and treatment for physical health conditions that, in turn, improve mental health. Recent studies on the NRPS show that pension promotes use of appropriate health care services, adherence to recommended treatment plans (Chen, 2017; Chen et al., 2017b), and nutritional intake (Cheng et al., 2018), with no apparent increase in unhealthy behavior, including smoking and alcohol drinking (Cheng et al., 2018).

Third, pension income may improve mental health through channel (iii), i.e., reduced psychosocial stress and adverse moods associated with financial hardship as well as increased self-esteem and sense of control (Fernald and Gunnar, 2009; Baird et al., 2013). While recent studies of the NRPS demonstrate higher probability of having sufficient financial support for daily expenses (Cheng et al., 2018), more empirical studies are required to directly test mental stress in response to pension benefits.

For enrollees not yet eligible for pension benefits (those younger than age 60), knowing that their own contributions to the individual account are matched by sizable government subsidies may reduce fear of future financial problems due to a strong commitment to saving for older ages and therefore serve to improve mental health through channel (iii). Grossman's framework predicts that even channels (i) and (ii) may yield some benefits for the younger cohort if they predict future pension income can lead to less disability and longer life expectancy, resulting in changes in current investment decisions. On the other hand, these potential beneficial effects can be muted by their premium payment (i.e. loss of income).

4. Methods

4.1. Data

We use the 2010 and 2012 waves of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), a nationally representative longitudinal survey, collected by Peking University. The baseline survey in 2010 included over 140 counties, 13,000 families and 30,000 adults in 25 out of 31 provinces in China. The 2012 follow-up wave successfully resurveyed more than 85 percent of the 2010 baseline sample. Since the NRPS was not yet introduced in most of the counties covered by the CFPS in 2010 and the mental health measures are not directly comparable across the two waves, only the 2012 survey is utilized in the main analysis. However, in robustness checks we do our best to construct a measure that is consistent across the 2010 and 2012 waves and include individual fixed effects to remove time invariant individual heterogeneity.

We consider all adults 45 years of age and above with rural registration (N = 8636) and divide into two distinct groups (ages 45–59 versus ages 60 and above) in our analysis. As noted above, at ages 45–59 individuals may pay a pension premium (i.e., a loss of current income), while at ages 60 or above individuals receive a monthly payment. We therefore expect the effects of pension enrollment to differ for these two age groups. While people below age 45 are required to contribute for at least 15 years to be eligible for NRPS, those age 45–59 at rollout may choose to contribute for any duration of time. We therefore would expect different effects by age.

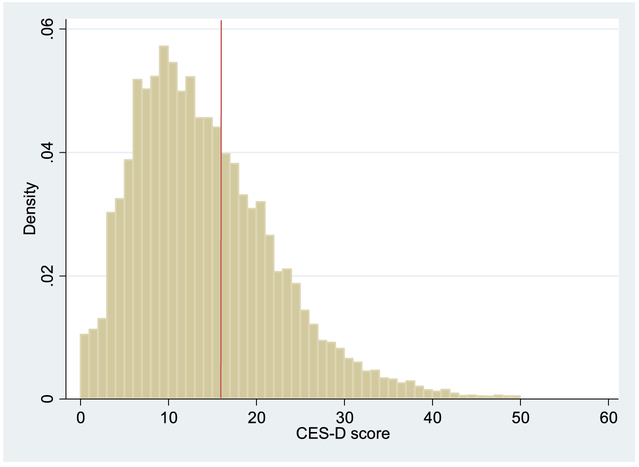

The CFPS survey collected rich information at the individual level, the household level, and the community level, including demographic characteristics, socioeconomic status, NRPS enrollment, mental health status (as measured by the CES-D), and subjective well-being (SWB). The CES-D, originally developed by Radloff (1977), is one of the most common screening tests for the depression quotient of individuals. Among all Chinese national survey datasets, CFPS uniquely contains a standard 20-item CES-D measure for mental health conditions during the past week. These 20 questions describe a list of feelings, including 16 questions on negative feelings and 4 questions on positive feelings. The respondents were asked to indicate how often they had those feelings or behaviors from the four options - “almost never (less than one day)“, “sometimes (1–2 days)“, “often (3–4 days)“, and “most of the time (5–7 days)“. The four options correspond to 0, 1, 2, 3 in negative questions and 3, 2, 1, 0 in positive questions. The possible total score ranges from 0 to 60. In addition to total CES-D score, we consider a binary indicator – depressive symptoms – which is often used to diagnose depression. An individual is diagnosed with depression symptoms if the CES-D total score is greater than 15 (Radloff, 1977; Bailly et al., 1992). Fig. 2 indicates the range and distribution of CES-D scores in the 2012 CFPS and suggests that a substantial proportion of respondents (36%) suffer from depressive symptoms.

Fig. 2.

Density of CES-D score.

Source: CFPS 2012

Notes: The red line represents the threshold for depressive symptoms (CES-D score 16 or greater).

4.2. Estimation strategy

The relationship between pension enrollment and mental well-being can be identified in the following equation:

| (1) |

where Yi denotes mental health, τ identifies the effect of Pensioni, denoted by a dichotomous variable whether the individual reported pension enrollment at the time of the survey and a continuous variable indicating self-reported pension income in the past month. We control for the polynomial (order k = 3) of age, other individual characteristics Xi, baseline county characteristics Ci, and provincial fixed effects Pi. Xi includes gender, ethnicity, cadre and party membership status, years of education, marital status, whether having chronic diseases, and if insured by a main type of health insurance in rural China initiated since 2003 and gradually covered all rural areas by the end of 2008 – New Cooperative Medical Scheme (hereafter NCMS). Ci includes the county's rollout year of the NCMS, NCMS enrollment rate, income per capita, and average years of schooling. Similar to Ayyagari and Frisvold (2016), we cluster estimates at the county level where the NRPS rolled out to account for correlations among individuals within each county. We run all analyses separately for our two age groups.

The key empirical challenge in identifying the causal effect of the pension (or more generally income) on mental health is that income changes can be endogenous. First, mental health may have a non-negligible impact on income. Second, unobserved factors omitted from the model, such as character, life experiences and social network, may affect both mental health and income and therefore can bias our estimations.

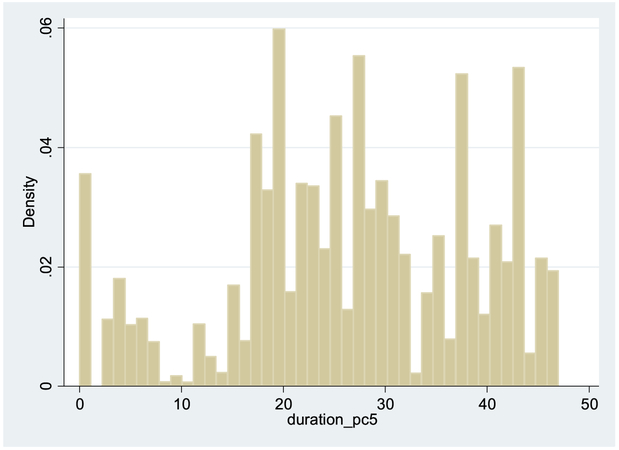

To avoid reverse causation and omitted variable bias and obtain unbiased and consistent estimates, similar to Cheng et al. (2018), we measure NRPS roll-out duration as the number of months between pension roll-out in a county and the month of survey administration. We use this variable to instrument for actual pension enrollment status and pension income. As previously described, the NRPS was first implemented in 2009 in a relatively small group of counties and gradually expanded to the rest of counties in 2010–2012. Fig. 1b plots the distribution of variable duration that varies substantially from almost 0 to 48 months.

Fig. 1b.

NRPS roll-out duration (number of months since the NRPS rollout in the county).

Source: CFPS 2012 survey

Note: NRPS duration is defined as number of months between the date of pension roll-out in the individual's county and the individual's survey month

The computational method we use to identify our IV estimates is two-stage least-squares (2SLS). The corresponding first stage equation of the 2SLS estimations is:

| (2) |

where Durationi, an instrument for Pensioni, is described above. Durationi must be strongly correlated with the endogenous explanatory variable Pensioni, conditional on other covariates. The justification is that older persons who were covered by the NRPS implementation (at the county level) for longer periods should be more likely to enroll in the scheme and receive pension income, because they may have better knowledge about the NRPS via peer learning or herding behavior. Similarly, though the younger cohort were not receiving pension income shortly after enrollment, many of them were expected to receive the payment in the near future, especially for those who were closer to the age 60 eligibility cutoff.

To be a valid instrument, Durationi, can only be correlated with mental health through its impact on pension enrollment or pension receipt. Though this exclusion restriction condition is not directly testable, we carry out a test to mitigate concerns about possible correlations between NRPS roll-out timing (set by the Ministry of Human Resources & Social Security) and unobservable county-level factors that may have a direct influence on mental health. We regress county-level NRPS roll-out duration on a rich set of county-level characteristics as well as a rich set of characteristics of key politicians (i.e. county party secretaries). The set of county characteristics include demographic factors (proportions of elderly and middle-aged persons respectively, population size, geographic size), economic factors (GDP per capita, industrial composition, county-level government annual spending and fiscal revenue), and public health facilities (number of hospital beds per capita). The rich database on party secretaries include a county's connections with the central government (if any major leaders of the central government were born or worked in the county) and demographic characteristics of party secretaries (age, gender, ethnicity, years of education, major). The finding of no significant association (Table A1 and Table A2) bolsters our confidence that NRPS timing is not independently correlated with mental health (except through pension enrollment).

5. Empirical results

5.1. Main results

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics of pension status, mental health, and covariates in the analysis. Comparing pension enrollees and non-enrollees, the former on average reported better mental health status in both older and younger cohorts. Meanwhile, the gap in mental health between pension enrollees and non-enrollees is larger for the older cohort than for the younger cohort. Next, we conduct more rigorous regression analyses to disentangle the effect of pension from other confounders. Our main results presented in Table 2 through Table 6 are limited to people age 60 and above, while the results for the younger cohort are in the Appendix.

Table 1.

Summary statistics.

Source: CFPS 2012

| dependent variable | All age groups | Age 45 to 60 | Age 60 or greater | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | NRPS participants | NRPS non-participants | All | NRPS recipients | NRPS non-recipients | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| CES-D | |||||||

| total score of CES-D | 14.53 (8.622) |

14.14 (8.500) |

13.77 (8.249) |

14.53 (8.735) |

15.35 (8.820) |

14.53 (8.443) |

16.85 (9.286) |

| depressive symptoms | 0.396 (0.489) |

0.382 (0.486) |

0.367 (0.482) |

0.397 (0.489) |

0.427 (0.495) |

0.389 (0.488) |

0.495 (0.500) |

| Pension | |||||||

| pension enrollment | 0.551 (0.497) |

0.506 (0.500) |

1 | 0 | 0.645 (0.479) |

1 | 0 |

| monthly pension income (100 CNY) | 0.189 (0.678) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0.589 (1.10) |

0.913 (1.25) |

0 |

| NRPS duration in the county | 26.87 (11.77) |

27.26 (11.78) |

28.89 (9.881) |

25.58 (13.25) |

26.04 (11.69) |

29.12 (8.749) |

20.46 (14.06) |

| Covariates at individual/family level | |||||||

| Age | 57.11 (9.054) |

51.99 (4.536) |

52.33 (4.517) |

51.63 (4.530) |

67.98 (6.196) |

68.20 (6.028) |

67.59 (6.476) |

| male | 0.489 (0.500) |

0.476 (0.499) |

0.464 (0.499) |

0.488 (0.500) |

0.518 (0.500) |

0.519 (0.500) |

0.515 (0.500) |

| Han | 0.913 (0.281) |

0.914 (0.280) |

0.916 (0.277) |

0.912 (0.284) |

0.911 (0.284) |

0.910 (0.287) |

0.915 (0.280) |

| CCP membership | 0.0585 (0.235) |

0.0482 (0.214) |

0.0484 (0.215) |

0.0480 (0.214) |

0.0803 (0.272) |

0.0830 (0.276) |

0.0755 (0.264) |

| married | 0.890 (0.312) |

0.943 (0.231) |

0.951 (0.216) |

0.936 (0.245) |

0.777 (0.416) |

0.780 (0.414) |

0.772 (0.419) |

| year of education | 4.566 (4.195) |

5.428 (4.260) |

5.433 (4.263) |

5.422 (4.256) |

2.735 (3.395) |

2.778 (3.403) |

2.655 (3.379) |

| NCMS | 0.909 (0.287) |

0.911 (0.285) |

0.971 (0.168) |

0.849 (0.358) |

0.906 (0.292) |

0.945 (0.228) |

0.836 (0.371) |

| chronic disease | 0.150 (0.357) |

0.135 (0.342) |

0.137 (0.344) |

0.133 (0.339) |

0.183 (0.387) |

0.184 (0.388) |

0.181 (0.385) |

| total assets (10,000 CNY) | 23.13 (56.02) |

24.39 (54.77) |

22.27 (31.73) |

26.56 (70.95) |

20.44 (58.50) |

17.92 (30.70) |

25.03 (88.89) |

| migration ratio | 0.112 (0.184) |

0.129 (0.192) |

0.128 (0.189) |

0.131 (0.194) |

0.0767 (0.160) |

0.0738 (0.158) |

0.0819 (0.163) |

| Covariates at county level | |||||||

| NCMS start year | 2005.7 (1.229) |

2005.7 (1.230) |

2005.7 (1.202) |

2005.7 (1.256) |

2005.7 (1.228) |

2005.7 (1.189) |

2005.8 (1.294) |

| NCMS enrollment ratio | 0.896 (0.106) |

0.892 (0.111) |

0.908 (0.0819) |

0.875 (0.132) |

0.904 (0.0968) |

0.906 (0.0817) |

0.898 (0.119) |

| Income per capita (100 CNY) | 102.053 (34.188) |

103.33 (35.262) |

100.332 (29.771) |

106.403 (39.889) |

99.341 (31.623) |

98.289 (29.096) |

101.254 (35.699) |

| Years of education | 5.577 (1.442) |

5.684 (1.448) |

5.685 (1.308) |

5.683 (1.580) |

5.349 (1.402) |

5.470 (1.212) |

5.131 (1.672) |

| N | 8636 | 5747 | 2869 | 2878 | 2889 | 1834 | 1055 |

Notes: [1] N is sample size; [2] Standard deviations are reported in the parentheses; [3] The variable “chronic disease” refer to the question “Were you diagnosed chronic disease in the past” in CFPS 2012. CFPS also record the name of the chronic disease if a respondent answered affirmatively. The three most common responses were hypertension, chronic gastritis, and lumbar intervertebral.

Table 2.

Main Results: Effect of NRPS enrollment (above 60-year-old).

| VARIABLES | First Stage | Second Stage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pension enrollment |

Total CES-D score | depressive symptoms | |||

| OLS | IV | OLS | IV | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Pension enrollment | −1.982*** (0.588) |

−6.202*** (2.377) |

−0.079*** (0.030) |

−0.175* (0.097) |

|

| NRPS duration in the county | 0.012*** (0.002) |

||||

| First stage F-statistic for IV | 25.97 | ||||

| Observations | 2764 | 2608 | 2585 | 2608 | 2585 |

Notes: [1] Covariates include individual/family level variables: cubic function of age, male, Han, CCP membership, married, years of education, NCMS, chronic disease, total asset, migration ratio, and county level variables NCMS starting year, NCMS enrollment ratio, income per capita and year of education. Full results are shown in Appendix Table A3. [2] ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. Standard errors clustered at the county level are reported in the parentheses.

Table 6.

The effect of pension on mental health (by each item in the CES-D scale, 2SLS estimates).

| Pension enrollment (0/1, 60 + age cohort) | Monthly pension income (100 CNY) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef | SE | Coef | SE | |

| CES-D questions | ||||

| 1. I was bothered by things that usually don't bother me. | −0.189 | 0.160 | −0.101 | 0.115 |

| 2. I did not feel like eating; my appetite was poor. | −0.172 | 0.163 | −0.191* | 0.113 |

| 3. I felt that I could not shake off the blues even with help from my family or friends. | −0.222 | 0.177 | −0.205 | 0.127 |

| 4. I felt that I was just as good as other people. | −0.166 | 0.316 | 0.019 | 0.195 |

| 5. I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing. | −0.414*** | 0.159 | −0.263** | 0.121 |

| 6. I felt depressed. | −0.260* | 0.157 | −0.236** | 0.116 |

| 7. I felt that everything I did was an effort. | −0.316* | 0.182 | −0.244* | 0.137 |

| 8. I felt hopeful about the future. | 0.110 | 0.309 | −0.023 | 0.153 |

| 9. I thought my life had been a failure. | −0.434** | 0.215 | −0.313* | 0.179 |

| 10. I felt fearful. | −0.266 | 0.181 | −0.229 | 0.166 |

| 11. My sleep was restless. | −0.450** | 0.177 | −0.342** | 0.159 |

| 12. I was happy. | 0.232 | 0.310 | −0.103 | 0.154 |

| 13. I talked less than usual. | −0.605*** | 0.211 | −0.432*** | 0.153 |

| 14. I felt lonely. | −0.371*** | 0.143 | −0.232* | 0.125 |

| 15. People were unfriendly. | −0.283* | 0.165 | −0.264** | 0.126 |

| 16. I enjoyed life. | 0.062 | 0.266 | −0.060 | 0.124 |

| 17. I had crying spells. | −0.164 | 0.147 | −0.182* | 0.102 |

| 18. I felt sad. | −0.134 | 0.133 | −0.143 | 0.103 |

| 19. I felt that people disliked me. | −0.186 | 0.149 | −0.204* | 0.106 |

| 20. I could not get “going.” | −0.134 | 0.205 | −0.240* | 0.143 |

| First stage F-statistic for IV | 25.97 | 19.33 | ||

Notes: [1] The response scale is reversed for four positive questions (4, 8, 12, 16), so that they have the same sign as those negative questions. 0 represents the best situation, 3 represents the worst situation. [2] The covariates are same as in Table 2. [3] ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. Standard errors clustered at the county level are reported in the parentheses.

In the first stage estimation we examine the correlation between county-level pension roll-out duration and individual pension enrollment, including the likelihood of pension enrollment (Table 2 & Table A5) and pension benefit size (Table 3). Results for the older cohort (age 60 and above) indicate that one additional month of pension roll-out increases the probability of enrollment by 1.2 percentage point (Table 2 column 1) and pension income by 1.7 CNY (Table 3 column 1). As expected, results indicate enrollment was slower among individual between age 45 and age 60 who were required to deposit money into their individual account upon enrolling. Results presented in Table A5 (column 1) show that one more month of pension roll-out increases enrollment rate by 0.7 percentage point in the younger cohort. As stated in the notes to the regression tables, the first stage F-statistics for the instrumental variable are above the usual threshold value for strong IV (i.e. 10), and most of them are above 80. Therefore, the NRPS duration at the county level is strongly positively correlated with individual pension enrollment status and (for those already above age 60) pension income. Consistent with Cheng et al. (2018), these results indicate that duration of pension rollout at the county level is a strong instrument for both pension enrollment and pension benefits.

Table 3.

Main Results: The Effect of NRPS income (above 60-year-old).

| VARIABLES | First Stage | Second Stage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly Pension income (100 Yuan) | Total Score of CES-D | depressive symptoms | |||

| OLS | IV | OLS | IV | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Monthly Pension income (100 Yuan) | −0.255 (0.195) |

−4.221** (1.884) |

−0.014 (0.010) |

−0.119* (0.072) |

|

| NRPS duration in the county | 0.017*** (0.004) |

||||

| First stage F-statistic for IV | 19.33 | ||||

| Observations | 2764 | 2608 | 2585 | 2608 | 2585 |

Notes: [1] Covariates include individual/family level variables: cubic function of age, male, Han, CCP membership, married, year of education, NCMS, chronic disease, total asset, migration ratio, and county level variables NCMS starting year, NCMS enrollment ratio, income per capita and year of education. Full results are shown in Appendix Table A4. [2] ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. Standard errors clustered at the county level are reported in the parentheses.

In the second stage, the effects of pension enrollment (Table 2) and pension income (Table 3) on mental health for the older cohort indicate that pension significantly improves mental health (as measured by the CES-D score) and depressive symptoms. The CES-D score of pensioners is, on average, 1.982 points lower than that of non-pensioners in the OLS regression, while it is 6.202 points lower in the IV estimations. The rates of depressive symptoms is17.5 percentage points lower among pensioners, respectively. The salient difference between the IV estimates and the OLS estimates indicates the importance of using the IV strategy to resolve the endogeneity of pension enrollment. The magnitude of these results indicate that a 100 CNY rise in monthly pension income decreases depressive symptoms by 11.9 percentage points.

Considering that the lowest pension payment in the NRPS is 55 CNY per month and that pension beneficiaries on average receive 91 CNY (column (6) of Table 1), the total effect of monthly pension benefits on depression is sizable. On average, receiving pension reduces the prevalence of depressive symptoms by 25.4 percent (0.119*0.91/0.427). To put this in context, one clinical trial found that treatment, either by medication or therapy, may reduce the prevalence of depression by 70.0–93.5 percent in low- and middle-income countries (Patel et al., 2007).

Our main findings in Table 2 also show that pension receipt decreases CES-D and depression symptoms by 0.70 and 0.35 standard deviations, respectively. This impact is similar in size to that of a divorce or being widowed in Britain (Gardner and Oswald, 2006), a medium size lottery win in Britain (Gardner and Oswald, 2007); the impact is half of that created by the immigration from Tonga to New Zealand (Stillman et al., 2009).

The effects of pension on younger enrollees are shown in Table A5. Although enrolling in pension may help the participants ensure against risks in old ages, the effects of NRPS are insignificant in the IV estimations and smaller in size than the effects on the older cohorts. On average, enrolling in the NRPS decreases CES-D score by 2.705 in the IV estimation. The rate of depressive symptoms decreases by 9.4 percentage points.

5.2. Robustness

In this section, a series of robust checks are described to provide reassurance that the main estimation results hold, especially for the older cohort.

First, we consider the subsample of urban residents who have no rural registration and therefore are ineligible to enroll in the NRPS. If the impact of pension enrollment is causal, and not driven by confounding factors, we should find no effect for these urban residents. As there is no actual pension enrollment for urban residents, we use a reduced form model and test the direct impact of NRPS rollout duration. We find the impact is nearly zero and insignificant for both the older and younger cohorts (Table A6, suggesting confounding factors are not driving our results.

Additional falsification tests examine the effect of pension enrollment on: 1) a 6-item CES-D score at the 2010 survey (for counties without pension roll-out) and height at the 2012 survey. The intuition is that pension enrollment should affect current mental health, rather than pre-determined mental health or long-term health status (which was determined before the NRPS expansions). If an individual's past mental health is associated with future pension enrollment, this indicate individuals' characteristics other than pension were driving the change in mental health status. The IV results are shown in Table A7. None of the coefficients on pension enrollment are statistically significant.

Although CES-D in CFPS 2010 only has 6-items and is not perfectly comparable with the more comprehensive measures of depression collected in CFPS 2012, we implement an IV fixed effect estimation following Cheng et al. (2018) to remove individual heterogeneity and predict the change in CES-D score percentile and depressive symptoms within individuals over time. Table 4 shows that for the older cohort pension enrollment is associated with 11.8 and 16.8 percentage points decline in CES-D score and the rate of depressive symptoms, respectively. This magnitude is similar to the main results presented in Table 2 and Table A5.

Table 4.

Robustness: Impact of NRPS on mental health (IV-FE using 2010–2012 Panel).

| CES-D score percentile | Depressive symptoms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | [45,60) | 60 + | [45,60) | 60 + |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Age specification: cubic age | ||||

| pension enrollment | 0.037 (0.072) |

−0.118*** (0.035) |

0.040 (0.127) |

−0.168*** (0.062) |

| First stage F-statistic for IV | 84.238 | 471.75 | 84.238 | 471.75 |

| N | 9092 | 4278 | 9092 | 4278 |

| Age specification: quadratic age | ||||

| pension enrollment | 0.035 (0.072) |

−0.118*** (0.035) |

0.042 (0.127) |

−0.168*** (0.062) |

| First stage F-statistic for IV | 84.744 | 388.325 | 84.744 | 388.325 |

| N | 9092 | 4278 | 9092 | 4278 |

Notes: [1] CES-D score percentile measures the relative ranking of CES-D score within each wave. [2] Depressive symptoms is defined as CES-D score ≥ 10 in 2010 wave following Andresen et al. (1994) and Zhang et al. (2012). However, the results should be treated with caution since the CES-D in Andresen et al. (1994) and Zhang et al. (2012) has same total score but different number of items compared to CFPS 2010. [3] The covariates are the same as in Table 2 except age. [4] ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

5.3. Heterogeneous effects

In this section, we discuss the heterogeneous effects of pension on mental health of older persons by mental health status, income, education, marriage status and the mental health measure. First, Table 5 shows results from the IV-quantile regression (IVQR) models. Except at the 10th quantile of the CES-D score, the point estimates are larger for higher quantiles (or worse mental health status).

Table 5.

Heterogeneous effect on CES-D Score (IV quantile regression).

| 10th quantile | 25th quantile | 50th quantile | 75th quantile | 90th quantile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRPS | |||||

| above 60-year-old | −3.786** (1.500) |

−2.773* (1.489) |

−5.165*** (1.739) |

−8.647*** (2.173) |

−11.534*** (3.218) |

| Pension Income (100 CNY) | |||||

| above 60-year-old | −2.538** (1.006) |

−1.859* (0.998) |

−3.463*** (1.166) |

−5.796*** (1.457) |

−7.732*** (2.157) |

Notes: [1] The 10th quantile for CES-D score points to better mental health than the other four quantiles. [2] F-statistics for “NRPS duration at the county level” in the first stage are respectively 240.25 and 87.51 for NRPS enrollment and NRPS income. [3] The covariates are same as in Table 2. [4] ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. Standard errors are reported in the parentheses.

Second, pension payment may account for a larger share of income for the poor, leading to heterogeneous impacts by income. We divide the sample of older cohort by income. Though the effects are less precisely estimated due to the smaller sample size, Panel A of Table A8 shows that pension enrollment and pension income mainly improve mental health of the lower income groups. This result indicates that pension benefits may release binding financial constraints for the poor segment.

Third, nearly one third of the rural respondents in the CFPS national sample are illiterate or semi-illiterate, defined as not completing primary education. To determine whether the effects we find differ by educational background, we divide the older cohort sample into three groups, including individuals who are illiterate or semi-illiterate, who completed only primary education, and those who completed secondary education. Panel B of Table A8 shows that pension income is the most effective in reducing depressive symptoms for the least educated group, which is consistent with recent evidence in the U.S. (Ayyagari, 2015).

Fourth, it is likely that families with couples both receiving pension may benefit more than others with one member receiving pension simply due to the doubling benefits. We divide the older cohort (age 60+) sample into two subsamples: single or married with spouse under age 60, and married with spouse over age 60. Note the number of married older persons with a spouse under age 60 are too small to perform 2SLS estimations separately so we group them with single older persons. This categorization enables us to distinguish the married couple both above age 60 from those with only one receiving pension benefit. However, Panel C of Table A8 does not indicate that families with more pension beneficiaries experienced larger effects, suggesting that pensioners do not use the income in such a way as to benefit their spouses.

Finally, looking into the results for each specific item of CES-D may help better understand potential mechanisms. Table 6 illustrates that a large proportion of all 20 items are significantly improved by pension enrollment and pension income, and several effects are sizable, such as “I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing.”, “I thought my life had been a failure”, “My sleep was restless”, “I talked less than usual”, “My sleep was restless”, and “I felt lonely”. Since many existing studies use various subsets of the full version of CES-D scale we use in this study, our results provide a cautious note that the specific basket of CES-D questions one includes may affect the impact identified. Though only two of the 6-item CES-D questions in CFPS 2010 have comparable questions in the 20-item CES-D in CFPS 2012, we form panels to test these two questions available in both waves. Consistently with Table 6, results in Table A11 suggest that pension enrollment improves the response to “I felt depressed” more than response to “I felt hopeless”.

6. Conclusions and discussion

The NRPS offers a modest but potentially important source of income to older populations in China. Employing a well-designed IV strategy, this paper provides new evidence of a positive causal relationship between income and mental health in old age, especially for those with educational, financial or health constraints. No such evidence was found for younger enrollees who have yet to receive any pension income.

A financial gain may generate more detectable improvement in subjective measures of health than in physical health in a short period of time (Baicker et al., 2013; Cesarini et al., 2013). Since CFPS were conducted shortly after NRPS roll-out, its potential impact on physical health may take longer to observe. Moreover, future studies may strengthen via exploring other population samples with similar scales and questions of CES-D measurement over waves.

Our findings have rich policy implications. First, they justify broad policy interventions that promote public health through increasing the availability of economic resources. Second, we demonstrate that mental health is an important component of research on the efficacy of welfare interventions. As such, mental health should be measured, reviewed, and addressed in policy recommendations, particularly in developing contexts where mental disorders have received less attention and where resources for improving mental health are most limited. Third, policymakers in China, as well as those in many other developing countries, are seeking to improve health of disadvantaged groups. The heterogeneous effects identified in this paper provide a reference in developing contexts. Fourth, this research draws attention to the poor mental health of the older population.

Our findings suggest that even a relatively modest pension may help improve the mental health of the Chinese population. Given that the cost of mental health treatment in LMICs amounts to 500–1000 USD per averted disability-adjusted life-year, commensurate with treatment and prevalence of diseases such as diabetes and HIV/AIDS (Patel et al., 2007), policies that offer certain segments of the population more income as a means of improving mental health might prove more cost-effective.

The NRPS achieved universal coverage at the county level in 2012, thus providing a nationwide, subsidized old-age support system to the older population in rural China. Since then, China has been rapidly implementing a social pension program for all eligible urban residents and has set an ambitious plan to integrate the rural and urban social pensions into one system, establishing a national pension system with the goal of providing wide coverage, basic security, multi-level options and sustainability. Once completed in 2020, this unified pension system is expected to serve more than 800 million residents in China. Our future work includes evaluating this more comprehensive and growing pension system.

Acknowledgements

Xi Chen is an assistant professor of health policy and economics at Yale University. Tianyu Wang is an assistant professor at Renmin University of China. Susan H Busch is a professor of health policy at Yale University. Financial supports from the James Tobin Research Fund at Yale Economics Department, Yale MacMillan Center faculty research award, the Claude D. Pepper Older American Independence Center Scholar Award (P30AG021342), and two NIH/NIA grants (K01AG053408; R03AG048920), MOE Project of Humanities and Social Sciences (17YJC790155) are acknowledged. Participants in PAA Annual Meetings 2016, Labor Economics Seminar at Yale, HPM Seminar at Yale, the NBER Summer Institute, ASHEcon, National University of Singapore, Clark University, the 2nd International Wellbeing Conference at Hamilton College, and the Thomas R. Ten Have Symposium on Statistics in Mental Health are acknowledged. Wen Jiang and Maya Mahin provided excellent research assistance. We appreciate the Institute of Social Science Survey at Peking University for providing us the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). The views expressed herein and any remaining errors are the authors' and do not represent any official agency. None of the authors have potential conflicts of interests that could bias this work.

Online Appendix

Table A1.

Summary Statistics for County-Level Characteristics

| Dependent variable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Description | Obs | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

| Time | Number of years since roll-out | 2032 | 1.757874 | 0.95823 | 0 | 3 |

| Independent variables (census data in 2010) | ||||||

| Variable | Description | Obs | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

| elderly | Proportion of residents aged > 60 | 2016 | 0.121858 | 0.02741 | 0.044787 | 0.245302 |

| primeage | Proportion of residents aged 45-59 | 2016 | 0.182595 | 0.0336 | 0.084766 | 0.281767 |

| Independent variables (China Data Center, averaged from 2006 to 2008) | ||||||

| Variable | Description | Obs | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

| population | Population with local Hukou (10,000) | 2032 | 46.96807 | 34.68808 | 0.673333 | 221.4667 |

| gdppc | GDP per capita (10,000) | 2098 | 1.3671 | 1.338048 | 0.158216 | 17.55029 |

| vaddedprim | Proportion of primary industry added value in GDP | 2032 | 11.72115 | 9.843006 | 0.126667 | 58.84 |

| netrevenue | Net revenue per capita of the local government (10,000) | 2032 | −0.13074 | 0.121803 | −1.48527 | 0.209573 |

| bed | Number of beds per 10,000 people in hospitals and orphanages | 2052 | 36.98728 | 19.73719 | 3.465704 | 210.4423 |

| Independent variables (Party secretary characteristics) | ||||||

| Variable | Description | Obs | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

| ifhometown | If it is the birth city | 2198 | 0.040902 | 0.198145 | 0 | 1 |

| age | Age | 2123 | 54.07195 | 3.494404 | 43 | 62 |

| age50 | Age below 50 | 2123 | 0.119379 | 0.324366 | 0 | 1 |

| age54 | Age 50-53 | 2123 | 0.253475 | 0.435179 | 0 | 1 |

| age58 | Age 54-57 | 2123 | 0.46852 | 0.499212 | 0 | 1 |

| ageover58 | Age above 58 | 2123 | 0.158626 | 0.365477 | 0 | 1 |

| Gender | Gender | 2129 | 0.980472 | 0.138428 | 0 | 1 |

| ifminority | Minority or not | 2111 | 0.072667 | 0.259697 | 0 | 1 |

| College | highest degree = B.A | 2161 | 0.265246 | 0.441627 | 0 | 1 |

| Master | highest degree = M.A | 2161 | 0.595151 | 0.491043 | 0 | 1 |

| Phd | highest degree = PhD | 2161 | 0.139603 | 0.346702 | 0 | 1 |

| partyschool | Graduated from the Party School or not | 2184 | 0.364161 | 0.481368 | 0 | 1 |

| major_agri | Major in agriculture | 2138 | 0.069506 | 0.254409 | 0 | 1 |

| major_humss | Major in humanities / social science | 2143 | 0.818317 | 0.385726 | 0 | 1 |

| major_tech | Major in science or technology | 2139 | 0.291262 | 0.454513 | 0 | 1 |

| major_medicine | Major in medicine | 2138 | 0.002242 | 0.047315 | 0 | 1 |

| Independent variables (other sources) | ||||||

| Variable | Description | Obs | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

| Ifpoor | National poverty-stricken county | 2032 | 0.283957 | 0.451027 | 0 | 1 |

| Auto | Autonomous county,state or region | 2032 | 0.30561 | 0.460779 | 0 | 1 |

Data sources: 1) county-level statistics (other than demographic characteristics) were drawn from the China Data Center at University of Michigan http://chinadatacenter.org/; 2) county demographic characteristics were drawn and averaged from China’s census data in 2000 and 2010; 3) prefecture-level party secretary information database 2000-2013 were compiled by China Insurance and Social Security Research Center at Fudan University (2015); 4) the national poverty-stricken county list in 2009.

Table A2.

County-Level Determinants of Years of NRPS Roll-out

| Variables | Number of years since initial roll-out in China | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| county demographic characteristics | |||

| Proportion of residents aged > 60 | −1.0912 (1.4380) |

−1.7857 (1.6366) |

0.7350 (2.5520) |

| Proportion of residents aged 45-59 | 2.6473 (1.6512) |

2.2985 (1.7937) |

3.3090 (2.7339) |

| Population with local Hukou (10,000) | 0.0008 (0.0009) |

0.0009 (0.0013) |

0.0012 (0.0013) |

| Autonomous county, state or region | −0.0682 (0.0853) |

−0.0708 (0.0855) |

−0.0867 (0.1997) |

| county economic and social characteristics | |||

| National poverty-stricken county | −0.0567 (0.0565) |

0.0429 (0.0923) |

|

| GDP per capita (10,000) | 0.0129 (0.0261) |

0.0467 (0.0406) |

|

| Proportion of primary industry added value in GDP | −0.0049 (0.0045) |

−0.0077 (0.0055) |

|

| Net revenue per capita of the local government (10,000) | 0.3892 (0.4447) |

−0.3473 (0.5908) |

|

| Number of beds per 10,000 people in hospitals and orphanages | −0.0023 (0.0015) |

−0.0014 (0.0030) |

|

| Key politician (party secretary) profile | |||

| Born in this municipality | −0.2310 (0.1629) |

||

| Age 50-53 | 0.2303 (0.1591) |

||

| Age 54-57 | 0.1247 (0.1556) |

||

| Age above 58 | 0.2120 (0.1759) |

||

| Male | 0.3716 (0.2371) |

||

| Minority | −0.0995 (0.1598) |

||

| highest degree = M.A | 0.0864 (0.1059) |

||

| highest degree = PhD | 0.0400 (0.1237) |

||

| Graduated from the Party School | −0.0156 (0.0972) |

||

| Major in agriculture | 0.1191 (0.1389) |

||

| major_medicine | −0.0058 (0.1598) |

||

| Major in humanities / social science | 0.1490 (0.1343) |

||

| Major in science or technology | 0.1289 (0.1038) |

||

| Province FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 2011 | 2009 | 1928 |

| Adjusted R-sq | 0.1171 | 0.0976 | 0.1901 |

Data sources: same as Table A1

Notes: [1] Column 1 presents results with county demographic characteristics. Column 2 adds other economic and social characteristics. Party secretary background variables are further included in Column 3. [2] Constants are omitted to save space. [3] ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. Standard errors are reported in the parentheses. [4] All the standard errors are clustered at the county level.

Table A3.

Main Results: The Effect of NRPS enrollment (above 60-year-old)

| First Stage | Second Stage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Pension enrollment | Total Score of CES-D | depressive symptoms | ||

| OLS | IV | OLS | IV | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Pension enrollment | −1.982*** (0.588) |

−6.202*** (2.377) |

−0.079*** (0.030) |

−0.175* (0.097) |

|

| NRPS duration in the county | 0.012*** (0.002) |

||||

| Personal characteristics | |||||

| Age | 1 574*** (0.316) |

9.109 (5.628) |

15.727** (6.467) |

0.471 (0.349) |

0.623* (0.358) |

| Age^2 | −0.021*** (0.004) |

−0.123 (0.077) |

−0.212** (0.088) |

−0.006 (0.005) |

−0.008* (0.005) |

| Age^3 | 0.000*** (0.000) |

0.001 (0.000) |

0.001** (0.000) |

0.000 (0.000) |

0.000* (0.000) |

| Male | 0.000 (0.014) |

−1.414*** (0.310) |

−1.396*** (0.298) |

−0.051** (0.021) |

−0.050** (0.021) |

| Han | 0.003 (0.060) |

0.177 (1.233) |

0.173 (1.176) |

−0.111 (0.075) |

−0.111 (0.072) |

| CCP membership | 0.012 (0.023) |

−1.606*** (0.524) |

−1.436*** (0.531) |

−0.036 (0.034) |

−0.033 (0.034) |

| Married | 0.017 (0.020) |

−2.193*** (0.397) |

−2.042*** (0.389) |

−0.116*** (0.019) |

−0.114*** (0.019) |

| Years of education | −0.002 (0.003) |

−0.285*** (0.055) 33 |

−0.304*** (0.055) |

−0.014*** (0.003) |

−0.015*** (0.003) |

| NCMS | 0.276*** (0.040) |

0.046 (0.630) |

1.236 (0.859) |

0.019 (0.031) |

0.046 (0.041) |

| Chronic disease | 0.004 (0.027) |

2.415*** (0.502) |

2.407*** (0.493) |

0.103*** (0.028) |

0.108*** (0.027) |

| Family characteristics | |||||

| Total assets | −0.000 (0.000) |

−0.008*** (0.003) |

−0.009*** (0.003) |

−0.000** (0.000) |

−0.000** (0.000) |

| Migration ratio | −0.013 (0.068) |

1.421 (1.130) |

1.419 (1.205) |

0.206*** (0.063) |

0.199*** (0.065) |

| Regional characteristics (county level) | |||||

| NCMS start year | −0.023 (0.025) |

0.364 (0.249) |

0.210 (0.245) |

0.020 (0.014) |

0.017 (0.013) |

| NCMS enroll rate | 0.200 (0.368) |

−9.097** (4.018) |

−8.750** (3.688) |

−0.531** (0.232) |

−0.523** (0.220) |

| Income per capita | −0.001 (0.001) |

−0.005 (0.011) |

−0.010 (0.015) |

−0.000 (0.001) |

−0.000 (0.001) |

| Average school years | −0.008 (0.021) |

−0.712** (0.304) |

−0.569* (0.297) |

−0.041*** (0.014) |

−0.038*** (0.014) |

| Province FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 7.575 (51.224) |

−922.947* (537.435) |

−775.422 (525.124) |

−51.455* (28.907) |

−48.114* (28.296) |

| First stage F-statistic for IV | 25.97 | ||||

| Observations | 2,764 | 2,608 | 2,585 | 2,608 | 2,585 |

Notes: ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. Standard errors clustered at the county level are reported in the parentheses.

Table A4.

The Effect of NRPS income (above 60-year-old)

| First Stage | Second Stage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Monthly Pension income (100 Yuan) | Total Score of CES-D | depressive symptoms | ||

| OLS | IV | OLS | IV | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Monthly Pension income (100 Yuan) | −0.255 (0.195) |

−4.221** (1.884) |

−0.014 (0.010) |

−0.119* (0.072) |

|

| NRPS duration in the county | 0.017*** (0.004) |

||||

| Personal characteristics | |||||

| Age | 69.713 (57.476) |

5.887 (5.662) |

7.828 (6.105) |

0.346 (0.347) |

0.400 (0.346) |

| Age^2 | −0.906 (0.776) |

−0.080 (0.078) |

−0.104 (0.084) |

−0.005 (0.005) |

−0.005 (0.005) |

| Age^3 | 0.004 (0.003) |

0.000 (0.000) |

0.000 (0.000) |

0.000 (0.000) |

0.000 (0.000) |

| Male | 0.512 (4.362) |

−1.422*** (0.318) |

−1.401*** (0.337) |

−0.051** (0.021) |

−0.050** (0.022) |

| Han | 15.240 (9.576) |

0.194 (1.287) |

0.805 (1.350) |

−0.109 (0.077) |

−0.093 (0.078) |

| CCP membership | −15.007** (6.438) |

−1.703*** (0.529) |

−2.161*** (0.626) |

−0.041 (0.034) |

−0.053 (0.036) |

| Married | 8.512* (4.732) |

−2.199*** (0.401) |

−1.818*** (0.424) |

−0.116*** (0.020) |

−0.108*** (0.020) |

| Years of education | 0.445 (0.666) |

−0.275*** (0.055) |

−0.272*** (0.062) |

−0.014*** (0.003) |

−0.014*** (0.003) |

| NCMS | 26.910** (12.585) |

−0.439 (0.633) |

0.603 (0.916) |

0.001 (0.032) |

0.028 (0.040) |

| Chronic disease | −5.433 (5.598) |

2.394*** (0.517) |

2143*** (0.547) |

0.102*** (0.028) |

0.100*** (0.029) |

| Family characteristics | |||||

| Total assets | −0.052 (0.060) |

−0.008** (0.003) |

−0.011** (0.004) |

−0.000* (0.000) |

−0.000** (0.000) |

| Migration ratio | −23.760** (11.554) |

1.395 (1.123) |

0.567 (1.270) |

0.204*** (0.063) |

0.175*** (0.064) |

| Regional characteristics (county level) | |||||

| NCMS start year | −4.973 (3.799) |

0.417 (0.267) |

0.146 (0.285) |

0.022 (0.014) |

0.015 (0.014) |

| NCMS enroll rate | −17.522 (93.022) |

−9.459** (4.338) |

−11.452** (5.133) |

−0.547** (0.242) |

−0.599*** (0.230) |

| Income per capita | 0.006** (0.002) |

−0.002 (0.011) |

0.024 (0.021) |

0.000 (0.001) |

0.001 (0.001) |

| Average school years | −8.771** (3.893) |

−0.760** (0.323) |

−0.879** (0.364) |

−0.043*** (0.014) |

−0.047*** (0.015) |

| Province FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 8,110.866 (7,869.202) |

−952.076* (574.143) |

−460.131 (623.283) |

−52.148* (29.724) |

−39.210 (30.476) |

| First stage F-statistic for IV | 19.33 | ||||

| Observations | 2,764 | 2,608 | 2,585 | 2,608 | 2,585 |

Notes: ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. Standard errors clustered at the county level are reported in the parentheses.

Table A5.

Other Results: The Effect of NRPS enrollment (between 45 and 60-year-old)

| First Stage | Second Stage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Pension enrollment | Total Score of CES-D | depressive symptoms | ||

| OLS | IV | OLS | IV | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Pension enrollment | −0.668* (0.343) |

−2.705 (3.070) |

−0.020 (0.018) |

−0.094 (0.168) |

|

| NRPS duration in the county | 0.007*** (0.002) |

||||

| Personal characteristics | |||||

| Age | −0.940 (0.790) |

−12.421 (12.790) |

−12.602 (12.849) |

0.100 (0.734) |

0.095 (0.727) |

| Age^2 | 0.019 (0.015) |

0.247 (0.245) |

0.252 (0.247) |

−0.002 (0.014) |

−0.002 (0.014) |

| Age^3 | −0.000 (0.000) |

−0.002 (0.002) |

−0.002 (0.002) |

0.000 (0.000) |

0.000 (0.000) |

| Male | −0.024** (0.011) |

−2.129*** (0.246) |

−2.203*** (0.250) |

−0.110*** (0.014) |

−0.114*** (0.014) |

| Han | 0.044 (0.061) |

−0.391 (0.754) |

−0.284 (0.779) |

−0.032 (0.042) |

−0.029 (0.041) |

| CCP membership | 0.001 (0.031) |

−0.986** (0.440) |

−1.091** (0.436) |

−0.064** (0.027) |

−0.070*** (0.026) |

| Married | 0.055* (0.029) |

−4.151*** (0.510) |

−3.969*** (0.561) |

−0.193*** (0.025) |

−0.185*** (0.028) |

| Years of education | 0.002 (0.002) |

−0.245*** (0.035) |

−0.241*** (0.035) |

−0.011*** (0.002) |

−0.011*** (0.002) |

| NCMS | 0.335*** (0.031) |

−0.659 (0.464) |

0.004 (1.145) |

−0.044* (0.026) |

−0.018 (0.061) |

| Chronic disease | −0.004 (0.020) |

3.707*** (0.349) |

3.657*** (0.346) |

0.157*** (0.018) |

0.156*** (0.018) |

| Family characteristics | |||||

| Total assets | −0.000 (0.000) |

−0.013*** (0.004) |

−0.013*** (0.004) |

−0.001*** (0.000) |

−0.001*** (0.000) |

| Migration ratio | −0.004 (0.052) |

2.247*** (0.743) |

2 137*** (0.739) |

0.060 (0.039) |

0.056 (0.039) |

| Regional characteristics (county level) | |||||

| NCMS start year | −0.031 (0.023) |

0.518** (0.210) |

0.435* (0.228) |

0.033*** (0.011) |

0.030** (0.012) |

| NCMS enroll rate | 0.312 (0.365) |

−1.073 (3.238) |

−0.753 (3.743) |

−0.042 (0.155) |

−0.035 (0.173) |

| Income per capita | 0.000 (0.001) |

0.003 (0.010) |

0.003 (0.011) |

0.000 (0.000) |

0.000 (0.000) |

| Average school years | −0.042** (0.021) |

0.151 (0.235) |

0.098 (0.274) |

0.006 (0.012) |

0.004 (0.014) |

| Province FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 77.244 (46.793) |

−812.217* (479.241) |

−644.889 (522.179) |

−68.069*** (25.487) |

−61.861** (28.282) |

| Observations | 5,543 | 5,447 | 5,421 | 5,447 | 5,421 |

Notes: [1] ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. Standard errors are reported in the parentheses. [2] For the cohort younger than age 60, pension enrollment means contributing pension premium. [3] All the standard errors are clustered at the county level. [4] This Table includes all respondents between 45 and 60-year-old who are eligible to enroll in the NRPS (i.e., above age 16, not in school, with rural registration).

Table A6.

Placebo Tests: Impact of NRPS duration on mental health in urban area

| VARIABLES | Total Score of CES-D |

Depressive symptoms |

N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2) | (3) | |||

| 45 to 60-year-old | NRPS duration in the county | 0.008 (0.027) |

−0.000 (0.001) |

1411 |

| above 60-year-old | NRPS duration in the county | 0.004 (0.030) |

0.001 (0.001) |

1234 |

Notes: [1] There is an Urban Residents Pension Scheme (URPS) in urban area starting at 2011 and gradually roll-out to the whole country. But the choices of pilot counties of URPS are independent from that of NRPS. [2] The covariates are same as in Table 2 except excluding NCMS. [3] ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. Standard errors are reported in the parentheses. [4] All the standard errors are clustered at the county level.

Table A7.

Placebo Tests: Impact of pension enrollment on pre-determined health outcome and long-term health status

| CES-D score in 2010 | Height (meter) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | [45-60) | 60+ | [45-60) | 60+ |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| pension enrollment | −1.484 (1.549) |

−0.761 (1.308) |

0.069 (0.140) |

−0.013 (0.162) |

| N | 5,487 | 2,701 | 5,543 | 2,764 |

Notes: [1] All results are using the same IV as above. [2] The covariates are same as in Table 2. [3] ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. Standard errors clustered at the county level are reported in the parentheses.

Table A8.

Heterogeneous Effects of Pension on Mental Health (2SLS Estimates)

| Pension enrollment (0/1, 60+ age cohorts) | Pension income (CNY, 60+ age cohort) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Panel A: by three income groups | ||||||

| dependent variable | low | middle | High | low | Middle | high |

| total score of CES-D | −6.891** (3.206) |

−6.248* (3.307) |

−3.921 (3.587) |

−0.079* (0.041) |

−0.050* (0.029) |

−0.016 (0.016) |

| depressive symptoms | −0.158 (0.138) |

−0.189 (0.166) |

−0.082 (0.153) |

−0.002 (0.002) |

−0.002 (0.001) |

−0.000 (0.001) |

| N | 826 | 847 | 852 | 826 | 847 | 852 |

| Panel B: ty education | ||||||

| illiterate | primary edu | secondary edu | illiterate | primary edu | secondary edu | |

| total score of CES-D | −8.867*** (2.742) |

−2.599 (2.972) |

−3.523 (5.487) |

−0.080*** (0.030) |

−0.012 (0.015) |

−0.015 (0.022) |

| depressive symptoms | −0.285*** (0.110) |

−0.022 (0.162) |

−0.230 (0.320) |

−0.003** (0.001) |

−0.000 (0.001) |

−0.001 (0.001) |

| N | 1,430 | 800 | 355 | 1,430 | 800 | 355 |

| Panel C: ty marriage status | ||||||

| single | single or spouse age<60 |

Married and spouse age 60+ |

single | single or spouse age<60 |

Married and spouse age 60+ |

|

| total score of CES-D | −3.963 (2.891) |

−6.592*** (2.535) |

−6.163*** (1.842) |

−3.458 (2.632) |

−5.303** (2.167) |

−3.868*** (1.311) |

| depressive symptoms | −0.036 (0.150) |

−0.243* (0.135) |

−0.152 (0.100) |

−0.031 (0.132) |

−0.196* (0.112) |

−0.096 (0.064) |

| N | 576 | 837 | 1,748 | 576 | 837 | 1,748 |

Notes: [1] 2SLS estimation results are reported. [2] Panel B uses income information collected during the 2012 wave, adjusted to 2010 constant prices. [3] The covariates in Panel A are same as in Table 2. [4] ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. Standard errors clustered at the county level are reported in the parentheses.

Table A9.

The Effect of NRPS with alternative age specification (above 60-year-old)

| NRPS enrollment | NRPS income | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Score of CES-D |

depressive symptoms |

Total Score of CES-D |

depressive symptoms |

|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Pension enrollment | −6.196*** (2.366) |

−0.179* (0.096) |

||

| Monthly Pension income (100 Yuan) | −4.222** (1.873) |

−0.122* (0.072) |

||

| Age [65,70) | 0.549 (0.413) |

0.001 (0.023) |

0.511 (0.460) |

−0.001 (0.023) |

| Age [70,75) | 0.421 (0.529) |

0.033 (0.028) |

0.441 (0.591) |

0.034 (0.029) |

| Age [75,80) | −0.141 (0.614) |

−0.033 (0.032) |

0.007 (0.674) |

−0.029 (0.034) |

| Age [80,85) | 1.020 (1.103) |

−0.014 (0.057) |

1.544 (1.316) |

0.001 (0.063) |

| Age [85,90) | 0.440 (1.593) |

−0.043 (0.090) |

0.483 (1.637) |

−0.042 (0.092) |

| Age [90,95) | 5.617 (3.565) |

0.292 (0.180) |

4.613 (4.386) |

0.263 (0.208) |

| Male | −1.405*** (0.297) |

−0.052** (0.020) |

−1.406*** (0.331) |

−0.052** (0.021) |

| Han | 0.128 (1.171) |

−0.114 (0.072) |

0.769 (1.343) |

−0.095 (0.078) |

| CCP membership | −1.422*** (0.527) |

−0.033 (0.033) |

−2.159*** (0.628) |

−0.054 (0.036) |

| Married | −2.052*** (0.385) |

−0.112*** (0.020) |

−1.800*** (0.424) |

−0.105*** (0.020) |

| Years of education | −0.295*** (0.055) |

−0.014*** (0.003) |

−0.267*** (0.062) |

−0.013*** (0.003) |

| NCMS | 1.277 (0.863) |

0.049 (0.041) |

0.633 (0.915) |

0.031 (0.040) |

| Chronic disease | 2.407*** (0.492) |

0.108*** (0.027) |

2.148*** (0.545) |

0.101*** (0.029) |

| Total assets | −0.009*** (0.003) |

−0.000** (0.000) |

−0.011** (0.004) |

−0.000** (0.000) |

| Migration ratio | 1.341 (1.214) |

0.196*** (0.066) |

0.515 (1.277) |

0.172*** (0.065) |

| NCMS start year | 0.229 (0.245) |

0.017 (0.013) |

0.166 (0.285) |

0.016 (0.014) |

| NCMS enroll rate | −8.655** (3.719) |

−0.519** (0.221) |

−11.479** (5.131) |

−0.600*** (0.230) |

| Income per capita | −0.010 (0.015) |

−0.000 (0.001) |

0.024 (0.021) |

0.001 (0.001) |

| Average school years | −0.577** (0.294) |

−0.038*** (0.014) |

−0.882** (0.361) |

−0.047*** (0.015) |

| Province FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | −427.203 (490.001) |

−33.588 (26.817) |

−305.714 (567.631) |

−30.079 (28.311) |

| First stage F-statistic for IV | 25.91 | 19.58 | ||

| Observations | 2,585 | 2,585 | 2,585 | 2,585 |

Notes: [1] 2SLS estimation results are reported. [2] The baseline age group is [60, 65). [3] ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. Standard errors clustered at the county level are reported in the parentheses.

Table A10.

The Effect of NRPS on Transfer to Children (above 60-year-old)

| NRPS enrollment | NRPS income | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | net transfer | financial support |

net transfer | financial support |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Pension enrollment | 158.781 (557.712) |

−0.050 (0.052) |

||

| Monthly Pension income (100 Yuan) | 104.271 (364.438) |

−0.033 (0.032) |

||

| First stage F-statistic for IV | 26.22 | 20.03 | ||

| Observations | 2,703 | 2,704 | 2,703 | 2,704 |

Notes: [1] 2SLS estimation results are reported. [2] The sample is limited to individuals who have children. [3] Net transfer (in CNY) is defined as the size of net transfer from parents to all non-resident children in the past year. Financial support (0/1) is defined as whether providing financial support to children in the past 6 months. [4] The covariates are same as in Table 2. [5] ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. Standard errors clustered at the county level are reported in the parentheses.

Table A11.

The Effect of NRPS enrollment on two comparable items of CES-D between CFPS 2010 and CFPS 2012 (Above 60-year-old)

| OLS | FE | N | First Stage F- Statistic for IV |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| I felt depressed. | −0.121*** (0.034) (0.037) |

−0.174*** (0.051) (0.056) |

4,512 | 329.006 |

| I felt hopeless. | −0.059 (0.036) |

−0.020 (0.057) |

4,478 | 326.291 |

Notes: [1] The CES-D question “I felt hopeless” in CFPS 2010 is phrased as “I felt hopeful about the future” in CFPS 2012. We therefore reversed the response scale in 2012 to match with the corresponding question in CFPS 2010. [2] The covariates are same as in Table 2. [3] ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. Standard errors are reported in the parentheses.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.12.004.

References

- Adda J, Banks J, von Gaudecker H, 2009. The impact of income shocks on health: evidence from cohort data. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc 7 (6), 1361–1399. [Google Scholar]

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL, 1994. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of. Prev. Med 10, 77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apouey B, Clark AE, 2015. Winning big but feeling no better? The effect of lottery prizes on physical and mental health. Health Econ. 24 (5), 516–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyagari P, 2015. Evaluating the Impact of Social Security Benefits on Health Outcomes Among the Elderly, vols. 2015–25 CRR WP, Boston College. [Google Scholar]

- Ayyagari P, Frisvold D, 2016. The impact of social security income on cognitive function at older ages. Am. J. Health Econom 2 (4), 463–488. [Google Scholar]

- Baicker K, Taubman SL, Allen HL, Bernstein M, Gruber JH, Newhouse JP, Schneider EC, Wright BJ, Zaslavsky AM, Finkelstein AN, 2013. The Oregon experiment—effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med 368 (18), 1713–1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailly D, Beuscart R, Collinet C, Alexandre JY, Parquet PJ, 1992. Sex differences in the manifestations of depression in young people. A study of French high school students part I: prevalence and clinical data. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr 1 (3), 135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird S, de Hoop J, Özler B, 2013. Income shocks and adolescent mental health. J. Hum. Resour 48 (2), 370–403. [Google Scholar]

- Byers AL, Yaffe K, Covinsky KE, Friedman MB, Bruce ML, 2010. High occurrence of mood and anxiety disorders among older adults: the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr 67, 489–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]