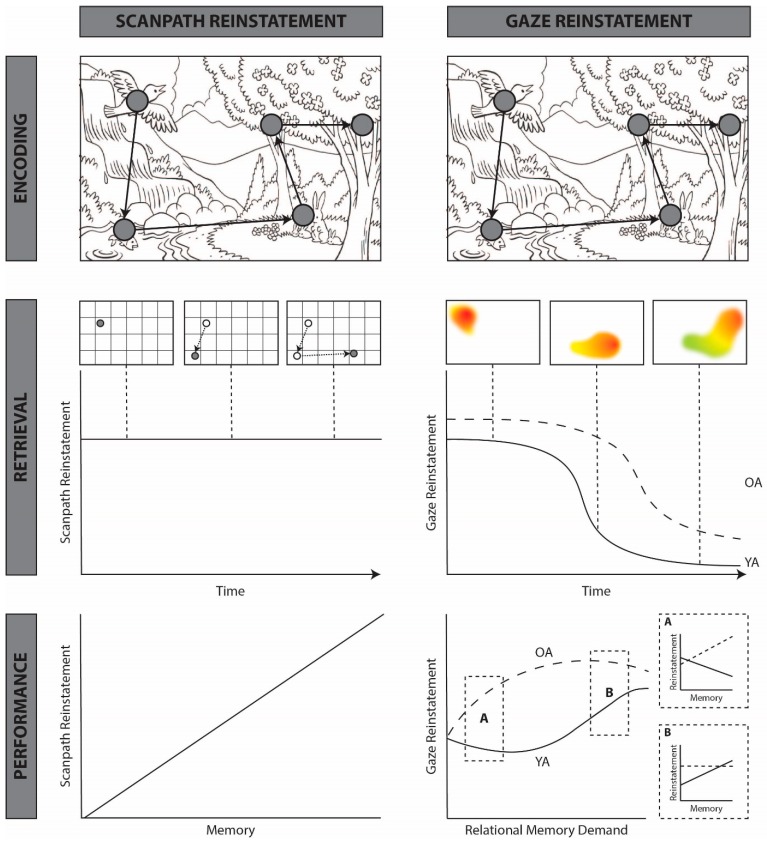

Figure 2.

Schematic comparing the predictions of the standard scanpath model (left) and the proposed gaze reinstatement model (right). Scanpath model (left): Row 1: a simplified scanpath enacted during the encoding of a line drawing of a scene. The same encoding scanpath is used to illustrate the predictions of both the scanpath model and the gaze reinstatement model (row 2, right). Row 2: the predictions of the standard scanpath model regarding retrieval-related viewing. In the present example, retrieval consists of visualization while “looking at nothing”. However, these predictions could similarly apply to repeated viewing of the stimulus. Early tests of scanpath theory used string similarity analyses to measure the similarity between encoding and retrieval fixation sequences [29,30,32]. These methods label fixations based on their location within predefined interest areas (often based on a grid, as shown here) and compute the number of transitions required to convert one scanpath into the other. Scanpath theory does not make any predictions regarding scanpath reinstatement over time or with memory decline [27,28]. Row 3: the predictions of the standard scanpath model regarding the relationship between reinstatement and mnemonic performance. The scanpath model predicts that scanpath reinstatement will be positively correlated with mnemonic performance [27,28]. Gaze reinstatement model (right): Row 1: a simplified scanpath enacted during the encoding of a line drawing of a scene. This is the same scanpath that is used to make predictions regarding the scanpath model (top left). Row 2: the gaze reinstatement model proposes that retrieval-related viewing patterns broadly reinstate the temporal order and spatial locations of encoding-related fixations. In the present example, gaze reinstatement decreases across time. This would be expected in the case of image recognition, wherein reinstatement declines when sufficient visual information has been gathered, e.g., [27,28,35,47], or in the case of image visualization, when the most salient parts of the image have been reinstated, e.g., [43,48]. The duration of gaze reinstatement would be expected to change based on the nature of the retrieval task (e.g., visual search, [37]). The gaze reinstatement model additionally predicts that reinstatement will be greater and extended in time for older adults (OA), relative to younger adults (YA) [36,37]. Row 3: The gaze reinstatement model (right) predicts that the relationship between reinstatement and mnemonic performance is modulated by memory demands (i.e., memory for spatial, temporal, or object-object relations) and memory integrity (indexed here by age). When relational memory demands are low (A), older adults, and some low performing younger adults, use gaze reinstatement to support mnemonic performance [36]. As demands on relational memory increase (B), the relationship between reinstatement and mnemonic performance in older adults plateaus, whereas younger adults use gaze reinstatement to support performance [36,43]. Based on findings from the compensation literature [49], we predict that as relational memory demands overwhelm older adults, gaze reinstatement will not be sufficient to support performance and will thus decline, whereas in younger adults, the relationship between gaze reinstatement and mnemonic performance would plateau before eventually declining as well.