Abstract

Polo-like kinase (PLK1) has been identified as a potential target for cancer treatment. Although a number of small molecules have been investigated as PLK1 inhibitors, many of which showed limited selectivity. PLK1 harbors a regulatory domain, the Polo box domain (PBD), which has a key regulatory function for kinase activity and substrate recognition. We report on 3-bromomethyl-benzofuran-2-carboxylic acid ethyl ester (designated: MCC1019) as selective PLK1 inhibitor targeting PLK1 PBD. Cytotoxicity and fluorescence polarization-based screening were applied to a library of 1162 drug-like compounds to identify potential inhibitors of PLK1 PBD. The activity of compound MC1019 against the PLK1 PBD was confirmed using fluorescence polarization and microscale thermophoresis. This compound exerted specificity towards PLK1 over PLK2 and PLK3. MCC1019 showed cytotoxic activity in a panel of different cancer cell lines. Mechanistic investigations in A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells revealed that MCC1019 induced cell growth inhibition through inactivation of AKT signaling pathway, it also induced prolonged mitotic arrest—a phenomenon known as mitotic catastrophe, which is followed by immediate cell death via apoptosis and necroptosis. MCC1019 significantly inhibited tumor growth in vivo in a murine lung cancer model without affecting body weight or vital organ size, and reduced the growth of metastatic lesions in the lung. We propose MCC1019 as promising anti-cancer drug candidate.

Abbreviations: 3-MA, 3-methyladenine; ABC, avidin-biotin complex; APC/C, anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome; BUBR1, budding uninhibited by benzimidazole-related 1; CDC2, cell division cycle protein 2 homolog; CDC25, cell division cycle 25; CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DAPKs, death-associated protein kinase; FBS, fetal bovine serum; FOXO, forkhead box O; HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α; IC50, 50% inhibition concentration; IHC, immunohistochemistry; Kd, the dissociation constant; LC3, light chain 3; MFP, M phase promoting factor; MST, microscale thermophoresis; MTD, maximal tolerance dose; Nec-1, necrostatin 1; PARP-1, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1; PBD, Polo box domain; PDB, Protein Data Bank; PI, propidium iodide; PLK1, Polo-like kinase; SAC, spindle assembly checkpoint

KEY WORDS: Polo-like kinase, PLK1, Polo box domain, Mono-targeted therapy, Cell cycle, Necroptosis, Spindle damage

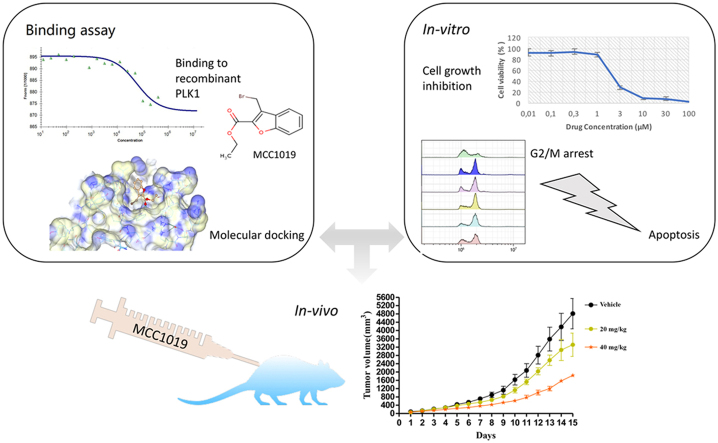

Graphical abstract

MCC1019 is a novel anticancer candidate that selectively targets PLK1. It mediates G2/M cell cycle arrest and cell death through induction of apoptosis and necroptosis. Inhibition of PLK1 downstream effectors like spindle assembly check points and cell growth pathway was well characterized. In vivo models revealed inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis.

1. Introduction

PLK1 is a member of the Polo-like kinase family1. It is one of the key main regulators of cell cycle division2. PLK1 acts in the M phase of the cell cycle through activation of the cyclin dependent kinase 1 (CDK1)–cyclin B complex3. It phosphorylates and activates cell division cycle 25 (CDC25) to foster the exit from mitosis through activation of anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) and the proteolytic machinery4. PLK1 is attached to the mitotic spindles through different stages of cell division5, which stabilizes the kinetochore–microtubule attachment and triggers the transition from meta- to anaphase6. PLK1 overexpression correlated with tumor progression and poor prognosis in different cancer types7., 8.. This makes PLK1 a promising target for anticancer therapy9. PLK1 inhibition induced cell death in different cancer types including pancreatic cancer10, breast cancer11 bladder cancer12 and oropharyngeal carcinomas13. Treatment with PLK1 inhibitors increased the overall survival rate of cancer patients in clinical studies compared to chemotherapy alone14.

Volasertib, a selective PLK1 kinase inhibitor, was granted the ‘orphan drug’ designation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Commission (EC) for acute myeloid leukemia15., 16.. This has raised interest to identify further novel PLK1 inhibitors. However, PLK1 kinase domain inhibitors such as volasertib and BI253615 showed inhibitory off-target effects towards other Ser/Thr kinases, mainly the death-associated protein kinases (DAPKs), which counteract cell death induced by PLK1 inhibition17.

PLK1 also contains a regulatory domain, the Polo box domain (PBD), which is characteristic for this family of kinases18. The PBD of PLK1 triggers specific subcellular localization by interacting with phosphorylation sites of targeted substrates19. Site-directed mutagenesis of the substrate binding site in PBD disrupted localization of PLK1 to mitotic spindles, centrosomes and the mitotic apparatus20. This leads to mitotic arrest and apoptotic cell death21. Substrate recognition by the PBD not only determines PLK1 localization, but also relieves the auto-inhibitory effect on the N terminal catalytic domain of PBD, resulting in kinase activation for target phosphorylation22. The PBD is found only among the members of the PLK family, which makes it an interesting target for PLK1 inhibition23.

In this study, we screened a library of 1162 compounds with the aim of identifying novel PLK1 inhibitors. The ability of one candidate compound identified during screening (3-bromomethyl-benzofuran-2-carboxylic acid ethyl ester; designated: MCC1019) to inhibit PLK1 was confirmed in biochemical assays. MCC1019 was able to inhibit cell growth and induce cell-cycle arrest in vitro. Treatment of a syngeneic murine lung cancer model with MCC1019 significantly inhibited tumor growth in vivo, suggesting that MCC1019 might be of interest for the treatment of human tumors.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Cell lines and culture

A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells and U87MG glioblastoma cells were obtained from the Tumor Bank of the German Cancer Research Center (DFKZ, Heidelberg, Germany), MCF-7 breast adenocarcinoma cells were obtained from Dr. Jörg Hoheisel (DKFZ), human lymphoblastic CCRF-CEM leukemia cells and their multidrug-resistant subline, CEM/ADR5000 were obtained from Prof. Axel Sauerbrey (University of Jena, Jena, Germany). Human HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells were obtained from American Type Cell Culture Collection (ATCC, USA). Human chronic myeloid leukemia K562 were obtained from the Tumor Bank (DKFZ). Human wild-type HCT116 (P53+/+) colon cancer cells were provided by Dr. B. Vogelstein and H. Hermeking (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Baltimore, MD, USA).

U87MG, MCF-7, HepG2 and HCT116 (P53+/+) cell lines were maintained in DMEM medium (Life Technologies, Schwerte, Germany), while A549, CCRF-CEM, CEM/ADR5000 and K562 cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies) in an incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Both media were supplemented with heat-inactivated 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany). Doxorubicin (Sigma–Aldrich, Schnelldorf, Germany) at a dose of 5 µg/mL was used for maintaining the multidrug-resistance phenotype of CEM/ADR5000 cells.

2.2. Chemical and reagents

A library of 1162 synthetic and semi-synthetic drug-like compounds was provided by MicroCombiChem GmbH (Wiesbaden, Germany).

2.3. Cytotoxicity screening

The cytotoxicity of 1162 compounds towards human drug-sensitive CCRF-CEM cells was screened using a resazurin reduction assay24. We applied a recently published protocol of the resazurin assay25. Briefly, cells were seeded in 96 well plates (104 cells/well) and then exposed to test compound at a single concentration (30 µmol/L) in a total volume of 200 µL for 72 h. Then, 20 µL of 0.01% resazurin were added to each well and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. Resazurin fluorescence was measured using an Infinite M2000 Pro plate reader (Tecan, Crailsheim, Germany) and used to calculate relative cell viability. Compounds were defined as cytotoxic, if exposure resulted in mean cell viabilities of less than 50% of the value for untreated cells.

The inhibition of growth of different cancer cell lines by MCC1019 was assessed using concentrations in a range from 0.001 to 100 μmol/L. Three independent experiments were performed with each six parallel measurements. The 50% inhibition concentration (IC50) values were calculated using calibration curves, by exponential linear regression using Eq. (1):

| (1) |

The analyses were performed using Prism 7 GraphPad Software (La Jolla, CA, USA).

2.4. Protein expression and purification

Cloning, expression and purification of the PLK1, PLK2 and PLK3 Polo-box domains have been previously described26. Briefly, the DNA sequence coding the PBD of human PLK1 (aa 326–603) was amplified by PCR from plasmid DNA and then cloned into a modified pET28a vector. The DNA sequences coding the PBDs of human PLK2 (aa 355–685) and PLK3 (aa 335–646) were amplified using PCR from placenta cDNA and cloned into a modified pQE70 vector carrying a C-terminal 63 His tag and an N-terminal MBP tag. Proteins were expressed in Rosetta BL21DE3 (Novagen) and purified using His·Bind® Resin (Merck) and dialyzed into buffer containing 50 mmol/L Tris (pH 8.0) 200 mmol/L NaCl (PLK1: 400 mmol/L NaCl), 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol, and 0.1% Nonidet P-40.

2.5. Fluorescence polarization assay

A total of 350 selected compounds were screened for binding to the PBDs of PLK1, PLK2, and PLK3 using a fluorescence polarization assay as described27., 28.. Briefly, 50 μmol/L of each compound was incubated with proteins (PLK1: 20 nmol/L; PLK2: 80 nmol/L; PLK3: 250 nmol/L) for 1 h at room temperature followed by the addition of 10 nmol/L of fluorescence-labeled peptide. Fluorescence polarization was measured after a further 1 and 2 h using a Tecan Infinite F500 384-well plate reader (Tecan, Crailsheim, Germany). The fluorophore-labeled peptides used were: PLK1 PBD: 5-carboxyfluorescein-GPMQSpTPLNG-OH; PLK2 PBD: 5-carboxyfluorescein-GPMQTSpTPKNG-OH; PLK3 PBD: 5-carboxyfluorescein-GPLATSpTPKNG-OH. The assays were performed in a buffer containing 10 mmol/L Tris (pH 8.0), 50 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 2% DMSO and 1 mmol/L DTT. Inhibition curves with MCC1019 were performed by incubating protein with concentrations ranging from 0.1 μmol/L to 100 μmol/L for 1 h at room temperature, followed by addition of peptide and incubation for a further 1 h at room temperature before measurement of fluorescence polarization. The experiments were performed in triplicate. Data were analysed with OriginPro software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA).

2.6. Microscale thermophoresis

Microscale thermophoresis (MST) was used as described29 for investigating ligand protein interactions between MCC1019 and full length recombinant PLK1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany) or the PLK1 PBD fragment. The procedure was previously reported30. Briefly, recombinant PLK1 and purified PLK1 PBD were labeled with Monolith™ NT.115 Protein Labeling Kit BLUE-NHS (NanoTemper Technologies, Munich, Germany). Then, PLK1 (200 nmol/L) or PLK1 PBD (500 nmol/L) were titrated against different concentrations of MCC1019. The reactions were performed in analysis buffer (50 mmol/L Tris buffer pH 7.0, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 10 mmol/L MgCl2 and 0.05% Tween 20). The samples were filled in standard capillaries and fluorescent signal measurement was performed using a Monolith NT.115 instrument (NanoTemper Technologies). The results were calculated with 20% LED power and 40% MST. The dissociation constant (Kd) of MCC1019 binding to PLK1 or PLK1 PBD were calculated, and fitting curves were generated using MO.affinity analysis software (Nano Temper Technologies).

2.7. Molecular docking

In silico molecular docking was performed using FlexX from LeadIT 2 .3.2 software (BioSolveIT, Sankt Augustin, Germany). The 3D protein structure of the PLK1 PBD was uploaded from RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB: 4 × 9R), and MCC1019 in mol2 format was retrieved from the Zinc Database 12 (ZINC03184477). The binding site was determined using a reference ligand of the crystal structure. The test ligand was then superimposed to the binding site and the active amino acids of the protein. The binding energies were calculated using the FelxX algorithm and were selected according to the top 10 poses of the ligand.

2.8. Visualization and HYDE scoring

SeeSAR v.7.2 from BioSolveIT was used for the estimation of free binding energies. SeeSAR visualizes the atom-based affinity contribution based on estimation of the HYDE score. The HYDE score evaluates atomic hydrogen bonding, desolvation and hydrophobic interaction31. As this calculation is based on atomic interaction, SeeSAR visualizes ligand protein interactions in a framework using coronas, in which green spheres represent favourable affinity and red ones represent unfavourable affinities. MCC1019 mol2 files were uploaded and docked to the PLK1 PBD crystal structure (PDB: 4 × 9R).

2.9. Cell cycle analysis

A549 cells treated with different concentrations of MCC1019 (10, 20, 30 or 40 µmol/L) for 24 h were fixed with cold 95% ethanol and incubated at 4 °C for 1 h. Then, cells were washed with PBS and stained with propidium iodide (PI, 50 μg/mL, Sigma–Aldrich) for 15 min at 4 °C. Cell cycle analysis was performed using a BD Accuri™ C6 flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany).

2.10. Western blot

A549 cells were treated with MCC1019 for the times indicated, then cells were washed with PBS. Protein extraction was then performed using M-PER® Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent including 1% HaltTM Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Scientific). Total protein concentrations were determined using a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). Membranes were incubated with blocking buffer [3% BSA in Tris-buffered saline Tween 20 (TBST)] for 1 h at room temperature. Then, membranes were incubated with primary antibodies [anti-BUBR1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-phospho-AKT (Ser473) antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling, Frankfurt, Germany), anti-phospho-FOXO1(Ser256) antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling), anti-HIF-1α antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling), anti-PTEN antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling), anti-PARP polyclonal rabbit antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling,), anti-LC3B polyclonal rabbit antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling), anti-beclin-1 polyclonal rabbit antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling), anti-PLK1 polyclonal rabbit antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling), anti-phospho-PLK1 (Thr210) polyclonal rabbit antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling), anti-cyclin B1 polyclonal rabbit antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling), anti-phospho-histone H 3 (Ser10) polyclonal rabbit antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling), or anti-β-actin polyclonal rabbit antibody (1:2000, Cell Signaling)] overnight at 4 °C. Then, HRP-linked anti-rabbit IgG (1:3000, Cell Signaling) was incubated with the membranes for 1 h. LuminataTM Classico Western HRP substrate (Merck Millipore Darmstadt, Germany) was used for detection, and the proteins were visualized using an Alpha Innotech FluorChem Q system (Biozym, Oldendorf, Germany). Data analysis was performed using Image Studio Lite software.

2.11. Immunofluorescence microscopy

A549 cells treated with 40 µmol/L of MCC1019 for 24 h were washed with PBS and fixed using 3.7% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 30 min. After blocking with 5% FBS and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 h at room temperature, rabbit α-tubulin antibody (ab52866, Abcam) was added for 2 h at room temperature. Secondary antibody goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488) was added for 1 h at room temperature. Wash steps after each antibody incubation were performed in triplicate with PBS. Cells were additionally stained using 2 µg/mL 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma–Aldrich), and mounted in Fluoromount-G® (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL, USA). An EVOS SL digital inverted microscope (Life Technologies) was used for fluorescent imaging.

2.12. Autophagy detection

Autophagy was assessed using the Autophagy Detection Kit (ab139484, Abcam). A549 cells were treated with 40 µmol/L of MCC1019 for 48 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation and washed using assay buffer (supplied in the Autophagy Detection Kit). Cells were re-suspended in 250 μL indicator-free cell culture medium containing 5% FBS, followed by incubation with a further 250 μL medium containing green stain solution (supplied in the Autophagy Detection Kit) at 37 °C for 30 min. Afterwards, cells were washed with assay buffer, and pellets were re-suspended in 500 μL assay buffer. Flow cytometric analysis was performed using the green (FL1) channel of a BD Accuri™ C6 flow cytometer.

2.13. Syngeneic murine tumor model

Eight-week-old C57BL/6 mice (male and female body weight 25 ± 5 g) were purchased from The Chinese University of Hong Kong, China. All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the “Institutional Animal Care and User Committee Guidelines” of the Macau University of Science and Technology, China. The animals were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in alternating 12-h light/dark cycles, and a temperature-controlled room with food and water ad libitum. Murine LLC-1 lung cancer cells (1 × 106 cells) and murine RM-1 prostate cancer cells (1×106 cells) were subcutaneously injected into the right dorsal region of the mice as previously described32. After tumors grew to a size of about 100 mm3, the mice were randomly divided into three groups (6–8 mice per group): (1) vehicle control, (2) treated with 20 mg/kg MCC1019, or (3) treated with 40 mg/kg MCC1019. MCC1019 was dissolved in 100 μL buffer (PEG400:ethanol:ddH2O = 6:1:3), and then intraperitoneally injected into mice daily for 16 days (LLC-1 model) or 14 days (RM-1 model). Body weight and tumor volume (mm3) were measured daily using balance and a Vernier caliper with the formula L × W2 × 0.52, where L was tumor length and W tumor width.

2.14. In vivo metastasis assay

Tumor and lung tissues were harvested at the end of animal experiments for molecular and histochemical analyses. Tumor samples were stored at –80 °C, then homogenized in cold PBS buffer and centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 rpm at 4 °C. Then, 10 μL of the pellet was added to 200 μL RIPA buffer for 1 h. Protein fractions were processed for immunoblot analysis as described above. The lung tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, cut into 5 μm sections, and processed for routine hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining. Five HE-stained lung sections, taken at 50 μm intervals, were examined by microscope for metastatic lesions. Samples were imaged using a Leica DFC310 FX camera and lung areas were calculated with the Leica Application Suit V4.4 software. Metastatic lung areas were calculated as Eq. (2):

| (2) |

To determine the maximal tolerance dose (MTD), sub-chronic toxic doses of MCC1019 were tested in C57BL/6 mice for 7 days. The mice were orally administered with 100 or 200 mg/kg MCC1019 for 7 consecutive days (n = 6). The survival and body weight of mice were monitored and recorded.

2.15. Immunohistochemistry

Sections of paraffin embedded tissues were used for immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis. Ultra-Sensitive ABC Peroxidase Rabbit IgG Staining Kit (ThermoFischer) was applied for the detection of protein expression. For antigen retrieval, citrate buffer (Sigma) was used for 20 min at 99 °C. Then, 3% H2O2 was applied for 10 min at room temperature to block endogenous peroxide. Normal goat serum was applied for 30 min. As primary antibody, anti-BUBR1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:100, Abcam) was incubated overnight at 4 °C. The secondary antibody, biotinylated affinity-purified goat anti-rabbit IgG, was added for 1 h. The avidin–biotin complex (ABC) was then added for 20 min. DAP Quanto substrate (ThermoFischer) was applied for 5 min followed by counter-staining with hemalaun solution (Merck). Tissues were dehydrated and scanned by Panoramic Desk (3D Histotech Pannoramic digital slide scanner, Budapest, Ungary). Quantification of stained slides was performed by panoramic viewer software (NuclearQuant, 3D HISTECH).

3. Results

3.1. MCC1019 is a PLK1-PBD inhibitor

Cytotoxicity screening of a library of 1162 compounds led to the identification of 350 cytotoxic candidates. These were subjected to a further high-throughput assay based on fluorescence polarization, where the compounds were tested for binding to the PBD of PLK1, followed by selection for selectivity to PLK1-PBD over binding of PLK2-PBD and PLK3-PBD. Compound MCC1019 preferentially inhibited PLK1 PBD and was chosen for further investigations.

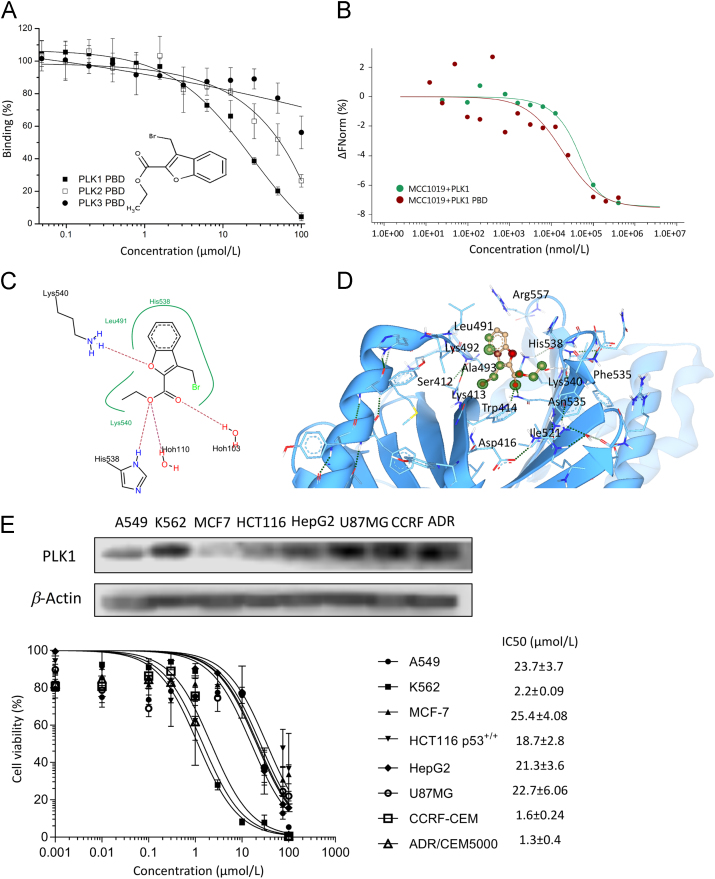

Dose–response curves of MCC1019 on binding of the peptide 5-carboxyfluorescein-GPMQSpTPLNG to PLK1 PBD gave an IC50 value of 16.4 ± 2.4 µmol/L (Fig. 1A). MCC1019 showed a 2.75-fold higher specificity for PLK1 PBD over PLK2-PBD (IC50 = 44.1 ± 14.4 µmol/L) and more than 6-fold higher specificity over PLK3 PBD (IC50 > 100 µmol/L).

Figure 1.

Inhibition of PLK1 PBD by MCC1019. (A) Inhibition of the binding of fluorescein-labeled phosphopeptides to PLK1, PLK2 or PLK3 PBDs by MCC1019 using a fluorescence polarization assay. The data are represented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. (B) Thermophoresis binding curve of MCC1019 to the PLK1 and PLK1 PBD obtained by microscale thermopheresis. (C) Surface visualization of molecular docking of MCC1019 to the PLK1 PBD (PDB: 4X9R). (D) SeeSAR visualization of MCC1019 binding to human PLK1 (PDB: 4X9R): HYDE corona coloring is based on atomic affinity: green for favourable and red for unfavourable predicted affinities between atoms and amino acids. (E) Dose response curves of MCC1019 for different cancer cell lines obtained by cytotoxicity resazurin reduction assay, with westernblot analysis of PLK1 expression on each cell. The data are represented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Binding of MCC1019 to whole enzyme PLK1 and PLK1 PBD were verified with microscale thermophoresis, a technique that tests the binding of compounds to proteins by assessment of the movement of particles under a temperature gradient33. Different concentrations (1:1 dilutions) of MCC1019 ranging from 0.02 to 400 µmol/L were titrated against 400 nmol/L of PLK1 or 500 nmol/L of PLK1 PBD, labeled with NT-495-NHS dye. Upon treatment with MCC1019, PLK1 and PLK1 PBD fluorescence decreased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). MCC1019 bound to PLK1 with a Kd value of 12.77 µmol/L (standard error of regression 0.406), while it bound to PLK1 PBD with a Kd value of 18.9 µmol/L (standard error of regression 1.13). An in silico molecular docking model suggested a high affinity of MCC1019 for the crystal structure of PLK1 PBD (PDB: 4×9R) with a FLexX score of –16.9 kJ/mol. The ligand receptor interaction (Fig. 1C) showed hydrogen bond interactions to the amino acids His538 and Lys540 in addition to the water molecules Hoh103 and Hoh110.

To perform a virtual structure activity relationship (SAR) analysis, we used SeeSAR 6 from LeadIT (Fig. 1D) to identify potential interactions between active sites in the MCC1019 scaffold and the PLK1 PBD binding pocket. For this purpose, we estimated the Hyde scoring function, which calculates the binding energy based on free dehydration energy and hydrogen bonding energy31. We found three atoms of MCC1019 that had the highest contribution to the overall score: (1) Br16 interacted with Trp414 and Lys413 (Hyde value: –3.1 kJ/mol), (2) C9 interacted with Leu49 and Ala493 (Hyde value: –3.8 kJ/mol), and (3) O5 interacted with Trp414 and Asn535 (Hyde value: –3.4 kJ/mol).

3.2. Cytotoxicity of MCC1019

MCC1019 exerted profound cytotoxicity across a panel of cancer cell lines. The 50% inhibition concentrations (IC50) of all tested cell lines as determined by the resazurin assay are shown in Fig. 1E. Hematologic malignancies (CCRF-CEM, K562 and CEM/ADR5000) were more sensitive to MCC1019 (IC50 < 2µmol/L) than cell lines from solid tumors (A549, MCF-7, HepG2, HCT116 and U87) (IC50 < 25 µmol/L). Interestingly, P-glycoprotein-expressing, multidrug-resistant CEM/ADR5000 cells were not cross-resistant to MCC1019, indicating that MCC1019 is not involved in the multidrug resistance phenotype.

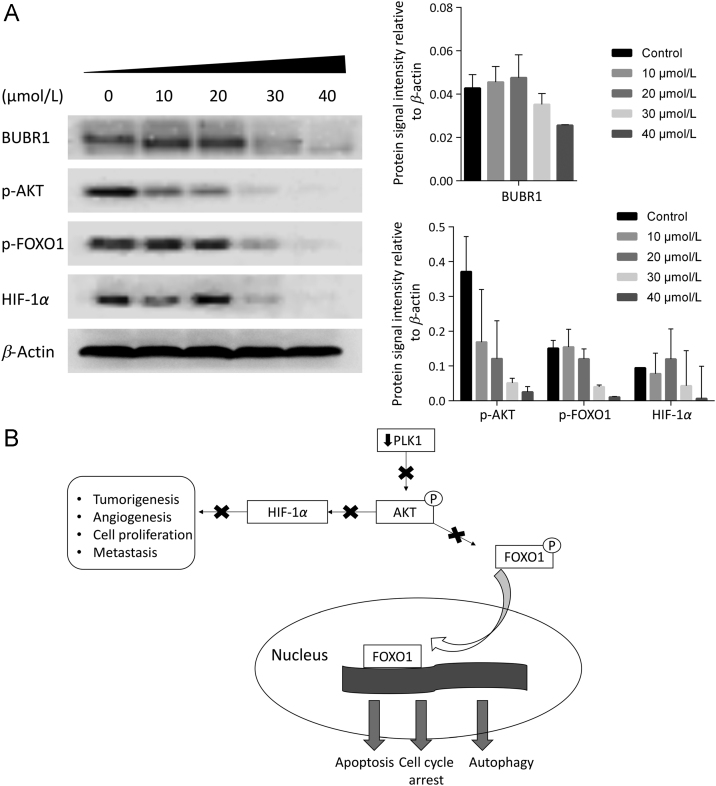

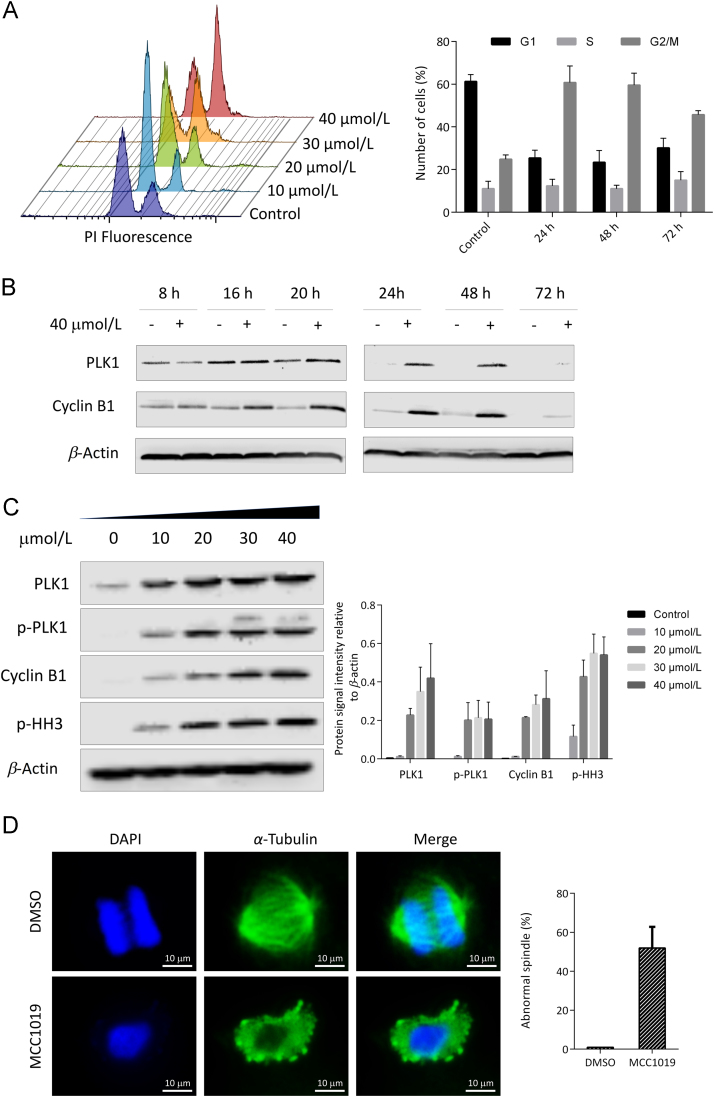

3.3. MCC1019 induce downregulation of PLK1 substrates

The down-regulation of PLK1 downstream proteins was examined by western blot. A considerable decrease in budding uninhibited by benzimidazole-related 1 (BUBR1) expression was noticed with increasing concentration of MCC1019 in A549-treated cells (Fig. 2A). Another important downstream protein is AKT. A reduction of AKT phosphorylation was noticed with increasing MCC1019 concentrations of A549 cells. Attenuation of AKT as important factor in cell growth was further confirmed by inhibition of downstream targeted proteins including p-FOXO1 and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α (HIF-1α) as shown in Fig. 2A. AKT signaling pathway is responsible for forkhead box O (FOXO) phosphorylation and localization to the cytosol, which therefore prevents nuclear transcription factor activation34. Active FOXO promotes apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and autophagy35., 36.. As shown in Fig. 2A, inhibition of AKT and therefore FOXO phosphorylation through MCC1019 led to FOXO activation.

Figure 2.

MCC1019 inhibit downstream effector proteins of PLK1. (A) Western blot analysis of BUBR1, p-AKT, p-FOXO1 and HIF-1α after treatment with different concentrations of MCC1019 for 24 h. Data represent relative expression intensity to β-actin, Error bars are ± SD of three independent experiments. (B) Diagram showing molecular effects of PLK1 inhibition on AKT signaling pathway that appeared in the study.

Another important targeted downstream candidate is HIF-1α37, which is considerably down regulated with MCC1019 treatment. A diagram explaining effect of PLK1 inhibition on FOXO1 and HIF-1α is shown (Fig. 2B).

3.4. MCC1019 induced M phase cell cycle arrest

Flow cytometry analysis revealed a concentration-dependent elevation of G2/M population of A549 cells by MCC1019 (Fig. 3A). To investigate the role of MCC1019 in the cell cycle, PLK1 and cyclin B expression was assessed at different time points. Compared to untreated control cells, MCC1019 induced higher expression levels of PLK1 and cyclin B1 after treatment for 24 and 48 h (Fig. 3B), indicating accumulation of cells in the mitotic phase with failure of cytokinesis completion. This was followed by lower expression levels after 72 h suggesting the initiation of cell death. For confirmation of this result, we monitored the expression levels of mitotic markers, i.e., phospho-PLK1, PLK1, cyclin B and phosphorylated Histone H3 (pHH3) S10 after treatment for 24 h. As shown in Fig. 3C, a concentration-dependent increase in the expression of these mitotic markers was found in treated A549 cells compared to untreated control cells.

Figure 3.

Induction of mitotic arrest by MCC1019. (A) Flow cytometric cell cycle analysis of exponentially growing A549 cells treated with MCC1019 for 24 h in a concentration range from 10 to 40 μmol/L. The data are represented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. (B) Western blot analysis of A549 cell lysates treated with MCC1019 for 8, 16, 20, 24, 48 or 72 h. Increased expression levels of PLK1 and cyclin B1 were seen after 24 h treatment. (C) Western blot analysis of the mitotic markers PLK1, cyclin B1 and p-HH3 after treatment with different concentrations of MCC1019 for 24 h. Data represent relative expression intensity to β-actin, Error bars are ± SD of three independent experiments. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis of A549 treated with MCC1019 and DMSO (control) and stained for α-tubulin (green) and DNA (blue). The data are represented as mean ± SD of cells undergoing mitosis.

3.5. Immunofluorescence microscopy

In order to assess whether the prolonged mitotic arrest induced by MCC1019 was consistent with inhibition of PLK1 function, we determined the effect of MCC1019 on mitotic spindles. A549 cells were incubated with MCC1019 for 24 h and stained with an antibody against α-tubulin and the DNA dye DAPI. MCC1019-treated cells showed multipolar spindle formation and fragmentation, consistent with the phenotype seen with PLK1 interference 38 (Fig. 3D). This result may explain the accumulation of mitotic cells as a result of the failure to organize mitotic microtubules, ultimately leading to cell death.

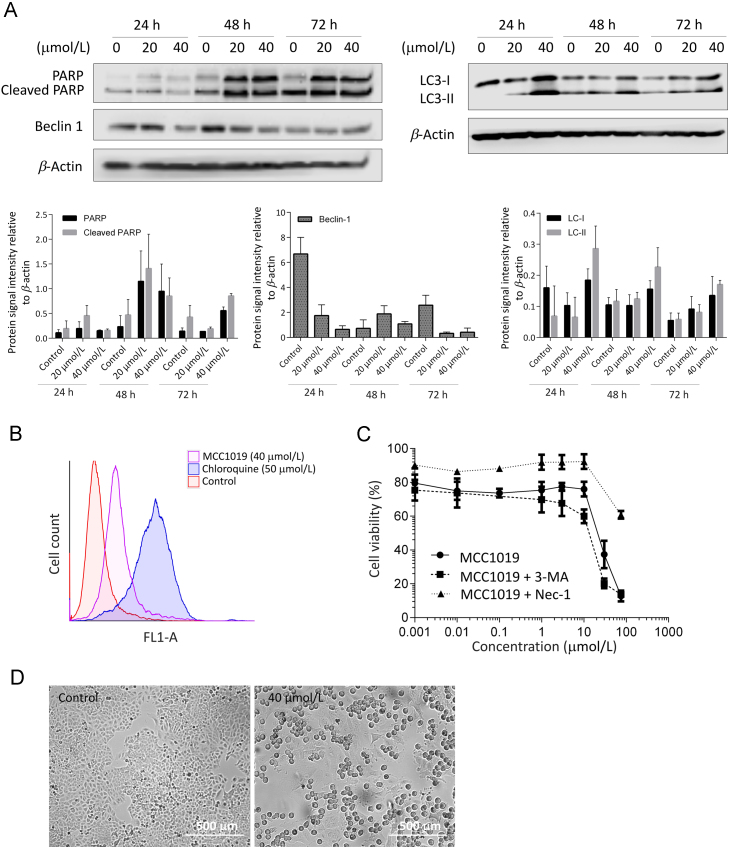

3.6. MCC1019 induced apoptosis and autophagy

We aimed to investigate different modes of cell death induced by MCC1019. First, we tested the induction of apoptosis by MCC1019. Western blot analysis showed increased poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) cleavage after 48 or 72 h treatment with MCC1019 (Fig. 4A), which indicated apoptosis as mode of cell death.

Figure 4.

Induction of apoptosis and necroptosis by MCC1019. (A) Western blot analysis of the apoptosis marker PARP and the autophagy markers LC3B and Beclin-1 in A549 cells treated with MCC1019 (20 or 40 μmol/L) for 24, 48 or 72 h. Data represent relative expression intensity to β-actin, Error bars are ± SD of three independent experiments. (B) Flowcytometric analysis of green dye signal for the detection of autophagy in A549 cells treated with MCC1019 (40 μmol/L) or chloroquine (50 μmol/L) as positive control. (C) Dose response curves of A549 treated with MCC1019 alone or in combination with 3 methyladenine (3-MA) or necrostatin-1 (Nec-1) obtained by cytotoxicity resazurin reduction assay. The data are represented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. (D) Images of A549 cells after 24 h treatment with MCC1019 (40 μmol/L) taken with Juli Br live cell analyzer.

Also, we investigated autophagy. Interestingly, MCC1019 increased the expression level of the autophagy marker light chain 3 (LC3-II) after treatment for 24, 48 and 72 h, indicating autophagosome formation (Fig. 4A). We confirmed autophagy induction by flow cytometry analysis of green detection reagent (supplied in the Autophagy Detection Kit). The right shift in the excitation and fluorescence emission spectra (463/534 nm) in Fig. 4B indicated autophagy induction.

Furthermore, to verify whether the increased autophagy was related to cell death, we investigated the effects of the autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine (3-MA) and necroptosis inhibitor necrostatin 1 (Nec-1) on the growth inhibitory effect of MCC1019 on A549 cells (Fig. 4C). No significant effect was observed upon treatment with 3-MA, indicating that in this case autophagy might be rather a tumor-protective mechanism. Necrostatin-1 treatment reversed cell growth inhibition induced by MCC1019, suggesting that MCC1019 induced cell death by necroptosis. The effect of MCC1019 on the morphology of A549 cell line is shown in Fig. 4D, where swelling of cells is evident.

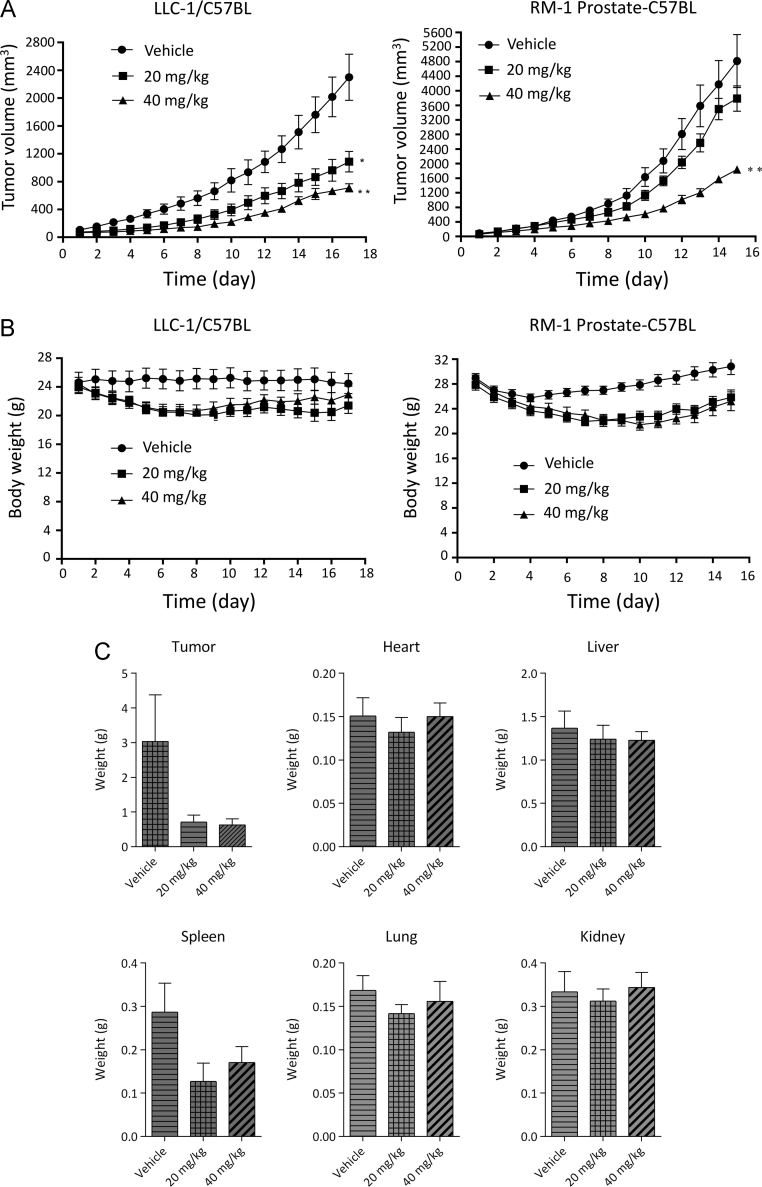

3.7. In vivo activity of MCC1019 in a syngeneic murine tumor model

The in vivo activity of MCC1019 was investigated using the murine LLC-1 lung cancer cell line and the murine RM-1 prostate cancer cell line. MCC1019 (20–40 mg/kg) was intraperitoneally injected daily into tumor-bearing mice. Tumor volume and body weight of mice were monitored daily. MCC1019 significantly inhibited tumor growth after two weeks of treatment compared to vehicle-treated control animals, which showed progressive tumor growth (Fig. 5A). LLC-1 lung tumors showed 51.1% and 68.1% inhibition by 20 and 40 mg/kg MCC1019, respectively. In addition, 40 mg/kg MCC1019 induced 61.5% tumor growth inhibition of RM-1 prostate tumors (Fig. 4B). These doses did not cause any significant change in body weight (Fig. 5B) or the weight of individual organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney, as shown in Fig. 5C) with the exception of the spleen. This result may be explained by the reported high PLK1 expression in the spleen39.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of tumour growth in vivo by MCC1019. (A) LLC-1 lung tumor bearing mice and RM-1 prostate tumor bearing mice models were used to determine the in vivo anti-tumor efficacy of MCC1019. (B) Total animal body weight changes were monitored after treatment with MCC1019 in both models. (C) Tumors and organs weight changes after MCC1019 treatment in LLC-1. The data are represented as mean ± SD (n = 6–8/group).

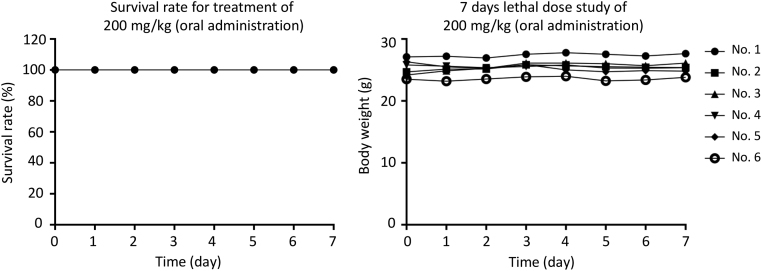

3.8. Safety assessment

To determine the safety of a higher dose of MCC1019 in vivo, C57/BL mice were orally administered with 200 mg/kg MCC1019 daily for 7 consecutive days (n = 6) and the survival and body weight of mice were monitored. After 7 days, all mice were still alive and did not show any significant reduction in body weight (Fig. 6). This result indicates that the therapeutic window of MCC1019 used in our experiments was safe enough for future drug development.

Figure 6.

Determination of the sub-chronic toxic dose of MCC1019. C57/BL/6 mice were orally administrated with 200 mg/kg MCC1019 for 7 consecutive days (n = 6). The survival and body weight of mice were monitored and recorded.

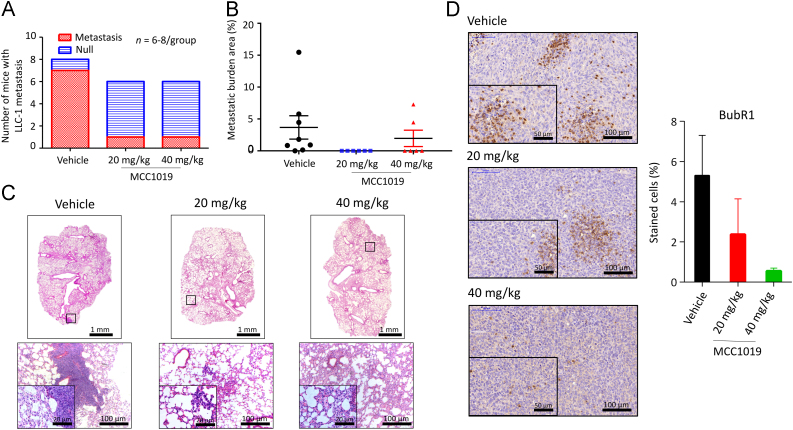

3.9. MCC1019 reduced the area of lung metastases

We examined the in vivo effects of MCC1019 on tumor metastasis. Metastatic areas in normal lung tissue of mice harboring LLC-1 tumors were inspected after 18 days of treatment with MCC1019. The metastatic area was calculated as Eq. (3):

| (3) |

As shown in Fig. 7A, the number of mice with lung metastasis decreased after treatment with two dosages of MCC1019 (one single metastatic lesion within six mice) compared to treatment with vehicle only (7 metastatic lesions within 8 mice). In addition, the size of the resulting lung metastatic lesions was quantified and showed the same tendency that was observed in metastasis frequency (Fig. 7B and C). The average of metastatic burden area per group was 4.1%, 0.1% and 2.1% for the vehicle control, MCC1019 (20 mg/kg) and MCC1019 (40 mg/kg), respectively. These results demonstrated the anti-tumor efficacy of MCC1019 in vivo by inhibiting tumor growth and metastatic progression.

Figure 7.

MCC1019 inhibits tumor metastasis in vivo. MCC1019 (20 and 40 mg/kg/day) suppressed the lung metastasis frequency. Lung tissue sections from MCC1019 or vehicle control-treated mice (LLC-1 bearing mice model) were stained by hematoxylin. Metastasized LLC-1 cancer cells with larger nuclei were visualized in lung tissues and captured from 6–8 animals of each group. Normal images, 10× magnifications; enlarged images, 40 × magnification. (A) The bar chart represents the number of mice that survived in each group. Number of mice with lung metastatic lesions (red area) and mice without metastatic lesion (blue area) are shown. (B) MCC1019 (20 and 40 mg/kg/day) reduced the metastatic burden area. The percentage of metastatic burden area is displayed. Each dot represents one mouse. Data represent mean ± SEM. **P≤0.01, Mann–Whitney t-test for comparison between vehicle and MCC1019 (20 mg/kg/day). (C) Representative H&E stained lung sections images with metastatic lesions. Infiltrating metastatic cells are detailed at higher magnification. (D) Immunohistochemical determination of BUBR1 expression in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded LLC-1 cancer cells. The data are represented as mean ± SD of six randomly selected sections.

Besides, immunohistochemical staining of LLC-1 tumors showed a downregulation of BUBR1 expression upon treatment with MCC1019 (Fig. 7D). This result matches with in vitro data and confirm direct attenuation of BUBR1 activity due to PLK1 inhibition.

4. Discussion

There is an emerging interest in developing new PLK1 inhibitors as anticancer agents. Our initial screening of 1162 compounds identified MCC1019 as potential novel PLK1 inhibitor with activity against the PBD of PLK1 and toxicity against CCRF-CEM leukemia cancer cells. Fluorescence polarization assays and microscale thermophoresis indicated that MCC1019 revealed high affinity for the PBD of PLK1, whilst binding to the PBDs of PLK2 and PLK3, which have tumor suppressor functions40., 41., was lower. Besides, MCC1019 showed high binding affinity to whole recombinant PLK1 enzyme. The binding site of PLK1 PBD consists of two halves: a hydrophobic half identified by amino acids Val411, Trp414, Leu490, and Leu491, and a positively charged half consisting of His538, Lys540, and Arg55742. Molecular docking of MCC1019 binding to PLK1 PBD and virtual structure activity relationship analysis suggested that MCC1019 interacts with Trp414 and His538.

In this study, we demonstrated important aspects regarding the activity of MCC1019 for cancer treatment. First, we reported a promising in vitro activity of MCC1019 in a panel of cancer cell lines. The susceptibility of drug-resistant CEM/ADR5000 cells to MCC1019 indicated that MCC1019 is not a substrate for the multidrug resistance protein P-glycoprotein, which causes drug efflux from cancer cells43. This suggests that refractory and otherwise non-responsive tumors may be treated with MCC1019.

Then, we addressed question whether the growth inhibitory effect of MCC1019 can also be detected on PLK1 downstream protein, e.g., AKT which is a known PLK1 substrate44. AKT is an important protein kinase that triggers survival, proliferation and growth of cancer cells45. Our results showed that MCC1019 terminated AKT activation and affected its downstream substrates. For example, FOXO a conserved AKT substrate showed decreased of phosphorylated form. This leads to an increase of the nuclear non-phosphorylated form of FOXO, which results in transcription of targeted genes. FOXO promotes the expression of pro-apoptotic genes of the BCL2 family46. FOXO also induces cell cycle arrest by enhanced transcription of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27kip1 47. Another important target for AKT signaling is HIF-1α. HIF-1α has an important role in transcriptional activation of genes responsible for tumorigenesis, angiogenesis and cancer development48., 49.. This effect is also attenuated as a result of PLK1 inhibition.

BUBR1 is a major player in spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC), a mechanism responsible for proving the proper attachment between chromosomes and spindles and though preventing chromosome mis-segregation50. PLK1 regulates BUBR1 and facilitate chromosome alignment51. MCC1019 treatment both in vitro and in vivo showed a considerable decrease in BUBR1 expression leading to mitotic defects.

The results of flow cytometry cell cycle analysis and monitoring of the expression level of mitotic markers with Western blot demonstrated that MCC1019 induced prolonged mitotic arrest. This can be explained by inhibition of the normal PLK1 functions in mitosis and cytokinesis.

The activation of M phase promoting factor (CDC2–cyclin B1 complex) represents a main driver of cell cycle progression through the M phase52. PLK1 mediates nuclear translocation of cyclin B1 during prophase and promotes the accumulation of active phosphatase CDC25C, which activates M phase promoting factor (MFP)53., 54.. An oscillation of PLK1 and MFP activity is mediated through negative feedback loops55, which explains the accumulation of mitotic markers upon prolonged treatment with MCC1019. Immunofluorescence microscopy indicated that mitotic arrest due to MCC1019-mediated PLK1 inhibition is a result of improper spindle formation and chromosomal alignment, which leads to mitotic catastrophe and cell death.

We also focused on the mode of cell death resulting from PLK1 inhibition by MCC1019. Late apoptosis took place after 48 h treatment as detected by increased cleavage of PARP. Cleaved PARP contains a DNA binding domain that binds to single- or double-stranded DNA breaks and is responsible for initiating damage repair 56., 57..

We also investigated autophagy and observed an increase of autophagy markers in MCC1019-treated A549 cells. However, treatment with 3-methyladenine, a selective PI3K inhibitor that inhibits autophagosome formation, did not prevent MCC1019-induced cell death. It is well known that autophagy has a dual role in cancer cells58. MCC1019-induced autophagy may play a protective role for cancer cells. Furthermore, we found that necroptosis represents another cell death mechanism of MCC1019, since co-treatment with necrostain-1 cells abolished the cytotoxicity of MCC1019.

We demonstrated that MCC1019 significantly inhibited tumor growth in vivo using murine syngeneic LLC1 lung and RM-1 prostate cancer models. MCC1019 did not exert significant toxicity as assessed by whole body or organ weight in treated mice even after 18 days of treatment with 40 mg/kg, although some spleen enlargement was observed. The safety of MCC1019 at higher doses was addressed by administering 100 and 200 mg/kg doses in C57BL/6 mice, where 100% survival was observed after 8 days of continuous treatment.

5. Conclusions

MCC1019 was identified as a selective inhibitor of PLK1 PBD. It showed activity against tumor cells both in vitro and in vivo. We present MCC1019 as a promising anti-cancer drug candidate worthy of further development.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG INST 268/281-1 FUGG and BE 4572/3-1, Germany). Sara Abdelfatah is grateful to the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) for a PhD stipend.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

Supporting data associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2019.02.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.Golsteyn R.M., Schultz S.J., Bartek J., Ziemiecki A., Ried T., Nigg E.A. Cell cycle analysis and chromosomal localization of human Plk1, a putative homologue of the mitotic kinases Drosophila polo and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cdc5. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:1509–1517. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.6.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nigg E.A. Polo-like kinases: positive regulators of cell division from start to finish. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:776–783. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80121-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackman M., Lindon C., Niggt E.A., Pines J. Active cyclin B1–Cdk1 first appears on centrosomes in prophase. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:143–148. doi: 10.1038/ncb918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Descombes P., Nigg E.A. The polo-like kinase Plx1 is required for M phase exit and destruction of mitotic regulators in Xenopus egg extracts. EMBO J. 1998;17:1328–1335. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosco A., Golsteyn R.M. Emerging anti-mitotic activities and other bioactivities of sesquiterpene compounds upon human cells. Molecules. 2017;22 doi: 10.3390/molecules22030459. :459-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanhaji M., Ritter A., Belsham H.R., Friel C.T., Roth S., Louwen F. Polo-like kinase 1 regulates the stability of the mitotic centromere-associated kinesin in mitosis. Oncotarget. 2014;5:3130–3144. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weichert W., Ullrich A., Schmidt M., Gekeler V., Noske A., Niesporek S. Expression patterns of polo-like kinase 1 in human gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:271–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li H., Wang H., Sun Z., Guo Q., Shi H., Jia Y. The clinical and prognostic value of polo-like kinase 1 in lung squamous cell carcinoma patients: immunohistochemical analysis. Biosci Rep. 2017;37 doi: 10.1042/BSR20170852. :BSR20170852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schöffski P. Polo-like kinase (PLK) inhibitors in preclinical and early clinical development in oncology. Oncologist. 2009;14:559–570. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mao Y., Xi L., Li Q., Cai Z., Lai Y., Zhang X. Regulation of cell apoptosis and proliferation in pancreatic cancer through PI3K/Akt pathway via Polo-like kinase 1. Oncol Rep. 2016;36:49–56. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu K., Law J.H., Fotovati A., Dunn S.E. Small interfering RNA library screen identified polo-like kinase-1 (PLK1) as a potential therapeutic target for breast cancer that uniquely eliminates tumor-initiating cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R22. doi: 10.1186/bcr3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seth S., Matsui Y., Fosnaugh K., Liu Y., Vaish N., Adami R. RNAi-based therapeutics targeting survivin and PLK1 for treatment of bladder cancer. Mol Ther. 2011;19:928–935. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthess Y., Raab M., Knecht R., Becker S., Strebhardt K. Sequential Cdk1 and Plk1 phosphorylation of caspase-8 triggers apoptotic cell death during mitosis. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:596–608. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pujade-Lauraine E., Selle F., Weber B., Ray-Coquard I.L., Vergote I., Sufliarsky J. Volasertib versus chemotherapy in platinum-resistant or-refractory ovarian cancer: a randomized phase II groupe des investigateurs nationaux pour l׳etude des cancers de l’ovaire study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:706–713. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudolph D., Steegmaier M., Hoffmann M., Grauert M., Baum A., Quant J. BI 6727, a polo-like kinase inhibitor with improved pharmacokinetic profile and broad antitumor activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3094–3102. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Döhner H., Lübbert M., Fiedler W., Fouillard L., Haaland A., Brandwein J.M. Randomized, phase 2 trial comparing low-dose cytarabine with or without volasertib in AML patients not suitable for intensive induction therapy. Blood. 2014;124:1426–1434. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-560557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raab M., Pachl F., Kramer A., Kurunci-Csacsko E., Dotsch C., Knecht R. Quantitative chemical proteomics reveals a Plk1 inhibitor-compromised cell death pathway in human cells. Cell Res. 2014;24:1141–1145. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowery D.M., Lim D., Yaffe M.B. Structure and function of Polo-like kinases. Oncogene. 2005;24:248–259. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang Y.-J., Lin C.-Y., Ma S., Erikson R.L. Functional studies on the role of the C-terminal domain of mammalian polo-like kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1984–1989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042689299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.García-Alvarez B., de Cárcer G., Ibañez S., Bragado-Nilsson E., Montoya G. Molecular and structural basis of polo-like kinase 1 substrate recognition: implications in centrosomal localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3107–3112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609131104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu F., Park J.-E., Qian W.-J., Lim D., Gräber M., Berg T. Serendipitous alkylation of a Plk1 ligand uncovers a new binding channel. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:595–601. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elia A.E.H., Rellos P., Haire L.F., Chao J.W., Ivins F.J., Hoepker K. The molecular basis for phosphodependent substrate targeting and regulation of Plks by the Polo-box domain. Cell. 2003;115:83–95. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00725-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berg A., Berg T. Inhibitors of the Polo-box domain of Polo-like kinase 1. ChemBioChem. 2016;17:650–656. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201500580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borra R.C., Lotufo M.A., Gagioti S.M., Barros F.D.M., Andrade P.M. A simple method to measure cell viability in proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. Braz Oral Res. 2009;23:255–262. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242009000300006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamdoun S., Fleischer E., Klinger A., Efferth T. Lawsone derivatives target the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in multidrug-resistant acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017;146:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reindl W., Yuan J., Krämer A., Strebhardt K., Berg T. Inhibition of Polo-like kinase 1 by blocking Polo-box domain-dependent protein–protein interactions. Chem Biol. 2008;15:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reindl W., Strebhardt K., Berg T. A high-throughput assay based on fluorescence polarization for inhibitors of the polo-box domain of polo-like kinase 1. Anal Biochem. 2008;383:205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reindl W., Gräber M., Strebhardt K., Berg T. Development of high-throughput assays based on fluorescence polarization for inhibitors of the polo-box domains of polo-like kinases 2 and 3. Anal Biochem. 2009;395:189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jerabek-Willemsen M., Wienken C.J., Braun D., Baaske P., Duhr S. Molecular interaction studies using microscale thermophoresis. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2011;9:342–353. doi: 10.1089/adt.2011.0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seo E.-J., Efferth T. Interaction of antihistaminic drugs with human translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) as novel approach for differentiation therapy. Oncotarget. 2016;7:16818–16839. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reulecke I., Lange G., Albrecht J., Klein R., Rarey M. Towards an integrated description of hydrogen bonding and dehydration: decreasing false positives in virtual screening with the HYDE scoring function. ChemMedChem. 2008;3:885–897. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200700319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Law B.Y.K., Qu Y.Q., Mok S.W.F., Liu H., Zeng W., Han Y. New perspectives of cobalt tris(bipyridine) system: anti-cancer effect and its collateral sensitivity towards multidrug-resistant (MDR) cancers. Oncotarget. 2017;8:55003–55021. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seidel S.A.I., Wienken C.J., Geissler S., Jerabek-Willemsen M., Duhr S., Reiter A. Label-free microscale thermophoresis discriminates sites and affinity of protein–ligand binding. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:10656–10659. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tzivion G., Dobson M., Ramakrishnan G. FoxO transcription factors; regulation by AKT and 14-3-3 proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1938–1945. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klotz L.O., Sánchez-Ramos C., Prieto-Arroyo I., Urbánek P., Steinbrenner H., Monsalve M. Redox regulation of FoxO transcription factors. Redox Biol. 2015;6:51–72. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webb A.E., Brunet A. FOXO transcription factors: key regulators of cellular quality control. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harada H., Itasaka S., Kizaka-Kondoh S., Shibuya K., Morinibu A., Shinomiya K. The Akt/mTOR pathway assures the synthesis of HIF-1α protein in a glucose- and reoxygenation-dependent manner in irradiated tumors. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:5332–5342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806653200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peters U., Cherian J., Kim J.H., Kwok B.H., Kapoor T.M. Probing cell-division phenotype space and Polo-like kinase function using small molecules. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:618–626. doi: 10.1038/nchembio826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clay F.J., McEwen S.J., Bertoncello I., Wilks A.F., Dunn A.R. Identification and cloning of a protein kinase-encoding mouse gene, Plk, related to the polo gene of Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:4882–4886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Syed N., Smith P., Sullivan A., Spender L.C., Dyer M., Karran L. Transcriptional silencing of Polo-like kinase 2 (SNK/PLK2) is a frequent event in B-cell malignancies. Blood. 2006;107:250–256. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang Y., Bai J., Shen R., Brown S.A.N., Komissarova E., Huang Y. Polo-like kinase 3 functions as a tumor suppressor and is a negative regulator of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha under hypoxic conditions. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4077–4085. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yin Z., Song Y., Rehse P.H. Thymoquinone blocks pSer/pThr recognition by plk1 polo-box domain as a phosohate mimic. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:303–308. doi: 10.1021/cb3004379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeino M., Saeed M.E.M., Kadioglu O., Efferth T. The ability of molecular docking to unravel the controversy and challenges related to P-glycoprotein—a well-known, yet poorly understood drug transporter. Invest New Drugs. 2014;32:618–625. doi: 10.1007/s10637-014-0098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cai X.P., Chen L.D., Song H. Bin, Zhang C.X., Yuan Z.W., Xiang Z.X. PLK1 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of gastric carcinoma cells. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8:4172–4183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vivanco I., Sawyers C.L. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang X., Tang N., Hadden T.J., Rishi A.K. Akt, FoxO and regulation of apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1978–1986. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li C.J., Chang J.K., Chou C.H., Wang G.J., Ho M.L. The PI3K/Akt/FOXO3a/p27Kip1 signaling contributes to anti-inflammatory drug-suppressed proliferation of human osteoblasts. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:926–937. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Semenza G.L. HIF-1 and mechanisms of hypoxia sensing. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:167–171. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Masoud G.N., Li W. HIF-1α pathway: role, regulation and intervention for cancer therapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5:378–389. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kops G.J.P.L., Weaver B.A.A., Cleveland D.W. On the road to cancer: aneuploidy and the mitotic checkpoint. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:773–785. doi: 10.1038/nrc1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsumura S., Toyoshima F., Nishida E. Polo-like kinase 1 facilitates chromosome alignment during prometaphase through BubR1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15217–15227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611053200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hunt T., Nasmyth K., Novak B. The cell cycle. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2011;366:3494–3497. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toyoshima-Morimoto F., Taniguchi E., Shinya N., Iwamatsu A., Nishida E. Polo-like kinase 1 phosphorylates cyclin B1 and targets it to the nucleus during prophase. Nature. 2001;410:215–220. doi: 10.1038/35065617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Toyoshima-Morimoto F., Taniguchi E., Nishida E. Plk1 promotes nuclear translocation of human Cdc25C during prophase. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:341–348. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feine O., Hukasova E., Bruinsma W., Freire R., Fainsod A., Gannon J. Phosphorylation-mediated stabilization of bora in mitosis coordinates Plx1/Plk1 and Cdk1 oscillations. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:1727–1736. doi: 10.4161/cc.28630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soldani C., Scovassi A.I. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 cleavage during apoptosis: an update cell death mechanisms: necrosis and apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2002;7:321–328. doi: 10.1023/a:1016119328968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smulson M.E., Simbulan-Rosenthal C.M., Boulares A.H., Yakovlev A., Stoica B., Iyer S. Roles of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation and PARP in apoptosis, DNA repair, genomic stability and functions of p53 and E2F-1. Adv Enzym Regul. 2000;40:183–215. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(99)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Levy J.M.M., Towers C.G., Thorburn A. Targeting autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:528–542. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material