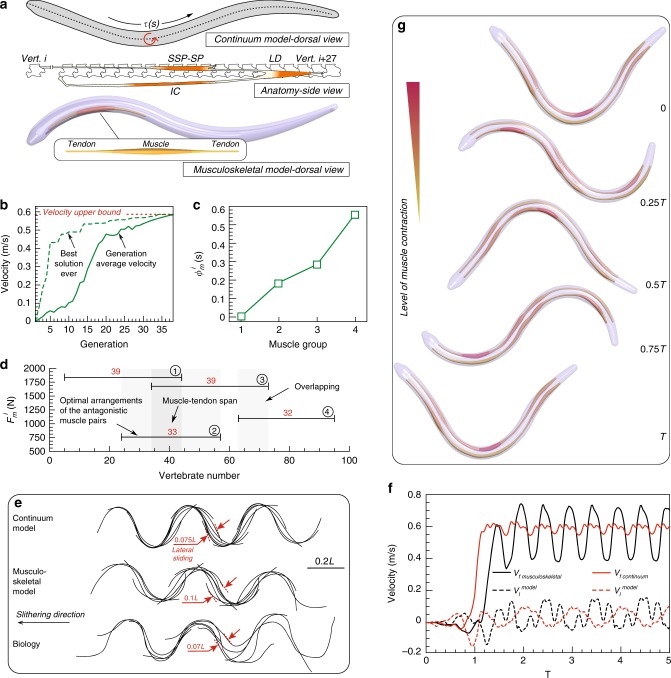

Fig. 3.

Emergent snake muscular architecture. a (Top) Continuum modeling of a snake with continuous torque profile along a uniform slender body64. (Middle) Sketch of the snake lateral muscle anatomy highlighting the epaxial muscle segment comprised of multiple muscles and tendons (adapted and modified with permission from Jayne81). (Bottom) Our simplified muscular snake model consists of a compliant continuum body and antagonistic muscle segments intervened between tendons. b The optimization course of the forward velocity as the snake’s musculoskeletal structure and activation patterns are evolved by the optimizer. Average velocity (within one generation) converges to the velocity upper bound provided by the model of Gazzola et al.64. c Identified optimal phase difference between muscle groups. d Identified optimal muscle arrangement: muscle groups’ span (detailed exploded view provided in Supplementary Fig. 3) and corresponding peak actuation forces . e Comparison between the fastest gait observed in the continuous reference64, our musculoskeletal model and experimental recordings of fast snakes characterized by similar Froude number80 (Scale bar, 0.2 L). f Forward and lateral velocity of continuous torque and musculoskeletal models. g Undulatory motion of snake slithering over one cycle, illustrating the level of contraction of each muscle at different phases over one actuation period. Settings: snake skeleton is modeled with length , maximum radius of , density and Young’s modulus (silicone rubber of intermediate stiffness)