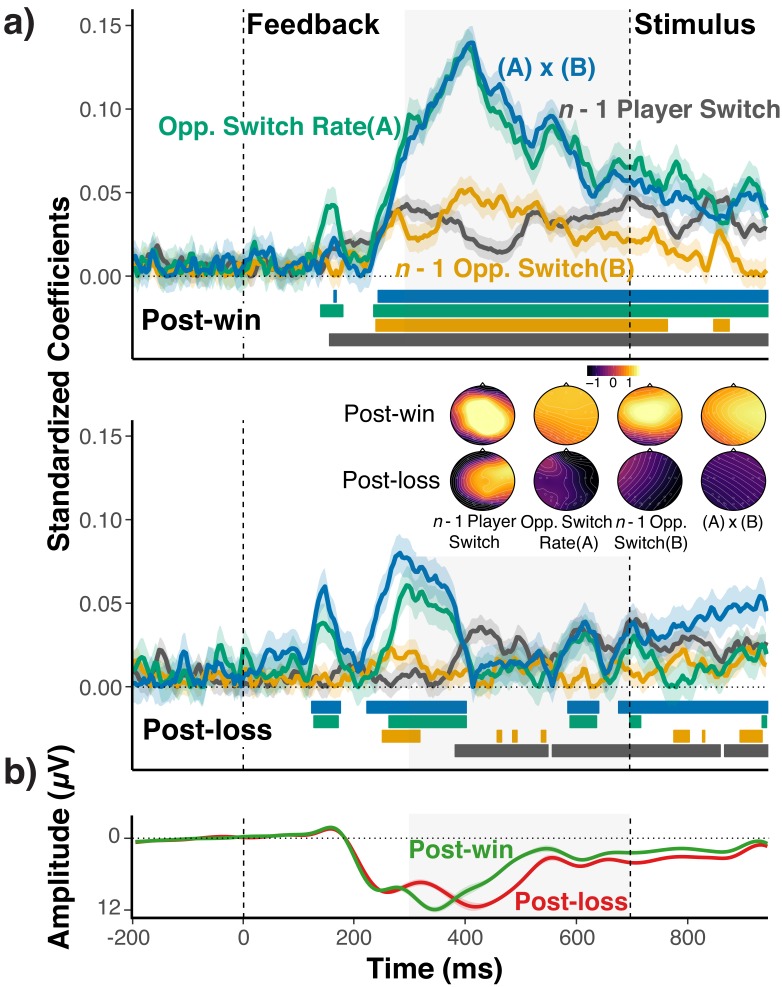

Figure 5. EEG-Analysis of choice-relevant information after wins and losses.

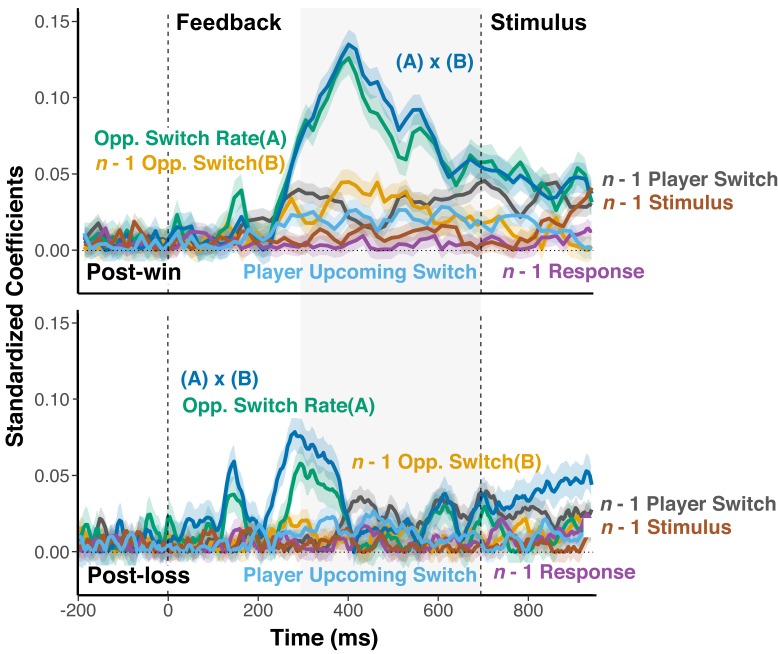

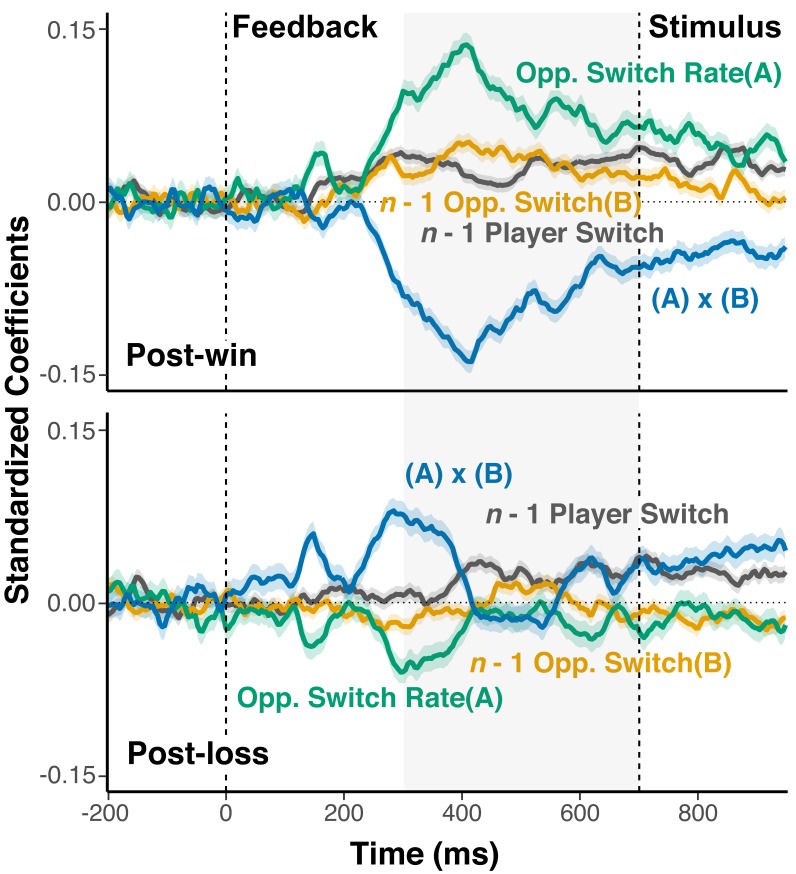

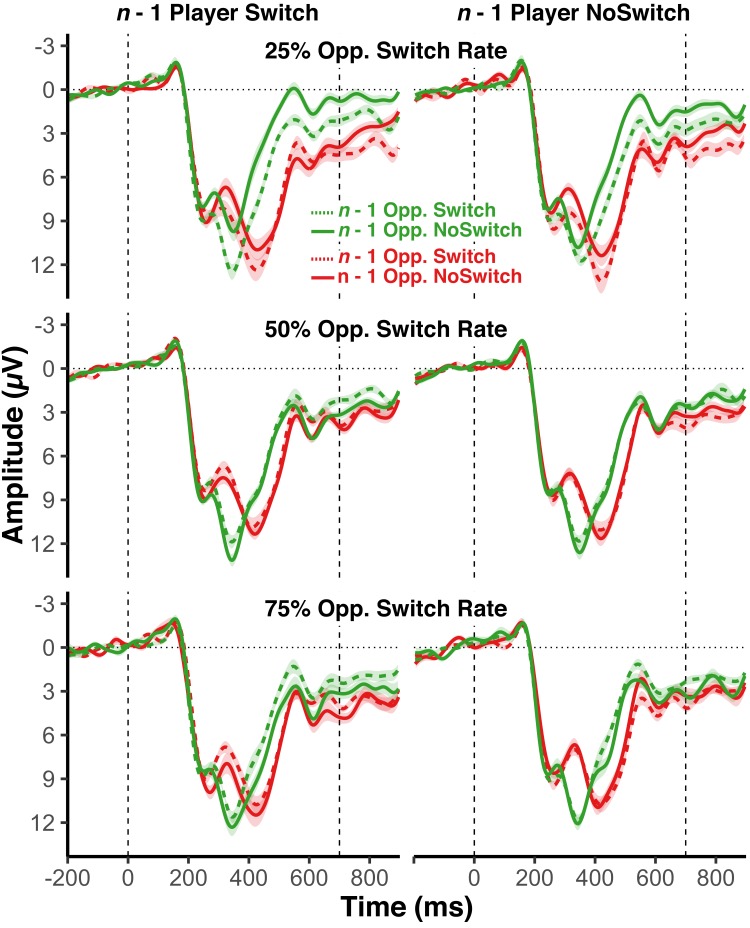

(a) Standardized coefficients from multi-level regression models relating EEG activity at Fz and Cz electrodes to the opponents’ overall switch rate (A), the n-1 opponent switch/no-switch choice (B), the n-1 players’ switch/no-switch choice, and the interaction between (A) and (B) for each time point and separately for post-win (upper panel) and post-loss (lower panel) trials. Shaded areas around each line indicate within-subject standard errors around coefficients. As coefficients for opponent-related predictors showed a marked, win/loss flip in sign, we again reversed the label of the post-loss predictors (see section Strategy for Testing Main Prediction and Figures 2 and 3; for signed coefficients, see Figure 5—figure supplement 2). For illustrative purposes, colored bars at the bottom of each panel indicate the time points for which the coefficients were significantly different from zero (p<0.05, uncorrected). See text for statistical tests of the predicted differences between coefficients for post-win and post-loss trials. The insert shows the topographic maps of coefficients that result from fitting the same model for each electrode separately. Prior to rendering, coefficients were z-scored across all coefficients and conditions to achieve a common scale. (b) Average ERPs for post-win and post-loss trials, showing the standard, feedback-related wave form, including the feedback-related negativity (i.e., the early, negative deflection on post-loss trials). Detailed ERP results are presented in Figure 5—figure supplement 3.