Abstract

The 2019 edition of the Canadian Chronic Disease Indicators (CCDI) provides recent estimates of the burden of chronic conditions and measures of general health and associated determinants in Canada. Using data from the CCDI and 2017 Canadian Community Health Survey, we explored the relationship between sociodemographic factors and selfreported mental health. Our findings suggest that sex (males vs females: adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 1.22); age (65–79 vs 35–49 year age group: aOR = 1.48); education (postsecondary graduate vs less than high school: aOR = 1.68); household income adequacy (highest quintile [Q5] vs lowest [Q1]: aOR = 2.25); and immigrant status (recent immigrants vs nonimmigrants: aOR= 2.29) were significantly associated with higher self-reported mental health.

Keywords: chronic conditions, mental health, public health, Canada, determinants of health, sociodemographic factors

Highlights

The Canadian Chronic Disease Indicators Quick Statistics table shows estimates of the burden of chronic conditions, measures of general health and associated determinants of health.

In 2017, more than two-thirds (70.3%) of the population in Canada reported having “excellent” or “very good” mental health.

Age, sex, province of residence, income quintile, education level and immigration status were sociodemographic factors significantly associated with self-reported mental health.

Introduction

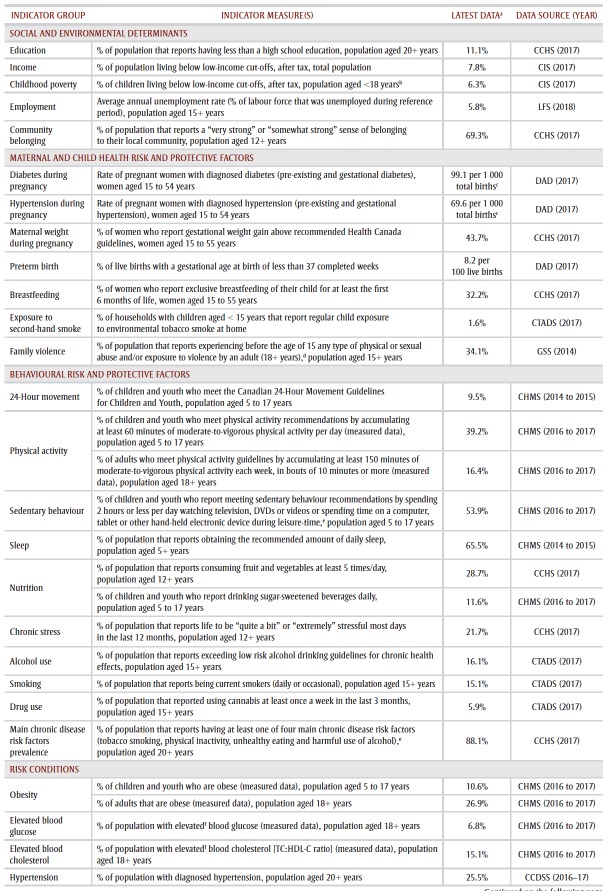

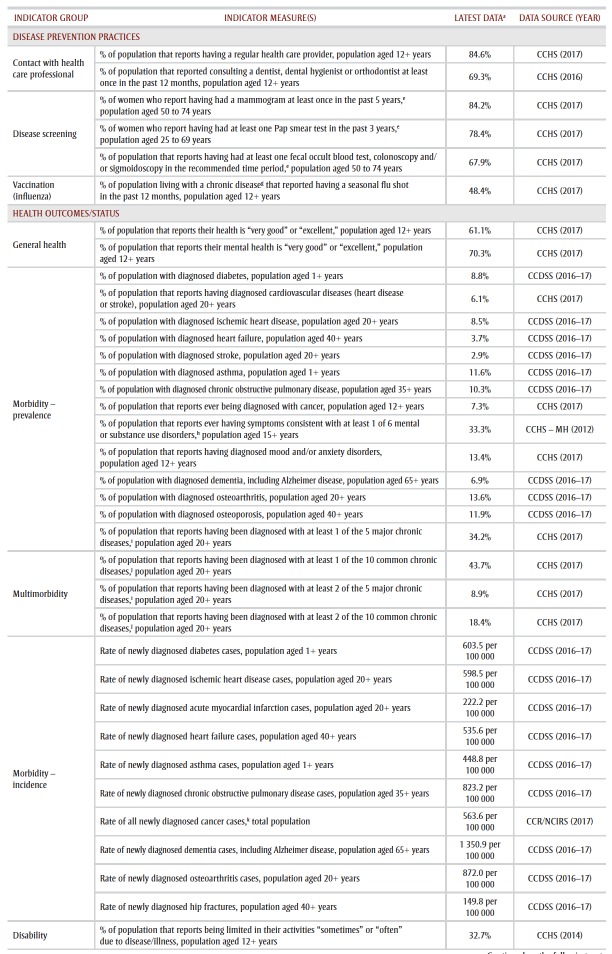

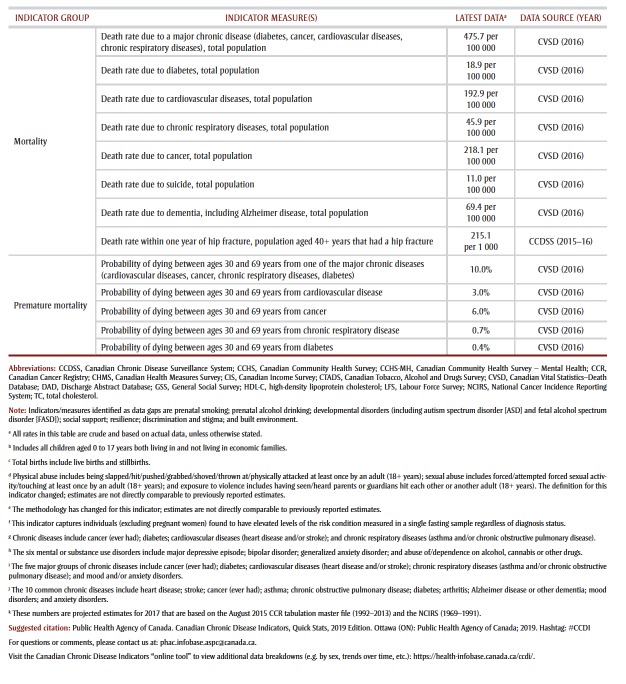

The Canadian Chronic Disease Indicators (CCDI) is a resource produced by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) that captures the burden of chronic conditions, and measures of general health and associated determinants. The CCDI is updated annually and is made publicly available through the CCDI summary document, Quick Stats (Table 1), and in the interactive CCDI Data Tool (https://infobase .phac-aspc.gc.ca/ccdi-imcc/).

Table 1. CANADIAN CHRONIC DISEASE INDICATORS QUICK STATS, 2019 EDITION.

The CCDI comprises six domains: (1) social and environmental determinants; (2) maternal and child health risk and protective factors; (3) behavioural risk and protective factors; (4) risk conditions; (5) disease prevention practices; and (6) health outcomes/status. Self-reported mental health status is a measure within the general health indicator group of the health outcomes/ status domain of the CCDI. This At-a-glance article presents the updated 2019 CCDI estimates and explores its mental health content to provide an indepth look at the distribution of selfreported mental health in Canada.

Mental health is a key outcome reported in the CCDI as it is intrinsically linked to, and has a bidirectional relationship with, physical health, behavioural and emotional processes and social factors.1-6 PHAC defines positive mental health as “a state of well-being that allows us to feel, think, and act in ways that enhance our ability to enjoy life and deal with the challenges we face.”7 Mental health promotion and mental illness prevention are key PHAC priorities.8 Indicators of mental health, such as self-reported mental health, disaggregated by sociodemographic factors, included in the CCDI Data Tool, provide important data to support policies and programs. These data will also help to inform PHAC’s collaborative work in mental health promotion as well as highlight areas for prevention of inequities among diverse populations.

PHAC and Statistics Canada identify selfreported mental health as a measure of the population’s general mental health status.9 Consistent with the PHAC Positive Mental Health Surveillance Indicator Framework (PMHSIF), the CCDI includes an estimate of the population in Canada who reported their mental health as “excellent” or “very good.” The estimate was assessed using data from the 2017 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) – Annual component. Respondents were asked, “In general, would you say your mental health is…?” Response options were as follows: “excellent,” “very good,” “good,” “fair” or “poor.” For this study, higher mental health includes respondents who reported their mental health as “excellent” or “very good.”

This At-a-glance article includes estimates for self-reported mental health disaggregated by sociodemographic factors, including age group, sex, province, rural/urban residence, income quintile, education level, Indigenous status, immigration status and length of time since immigration. Estimates were weighted with the survey sampling weight, and variance was estimated using the bootstrap method to account for the complex survey design. An adjusted logistic regression model was used to examine the relationship between sociodemographic factors and self-reported mental health. Reference groups were chosen based on adjusted odds ratios (aORs), not on prevalence rates. The category with the lowest adjusted odds of higher mental health was chosen as the reference group for easy and consistent interpretation. All statistical analyses were executed using SAS Enterprise Guide version 5.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Main findings

Table 1 displays the 2019 CCDI Quick Stats for all indicators. Data from the 2017 CCHS – Annual Component indicate that 70.3% of the population in Canada (n = 36 024) self-reported their mental health as “excellent” or “very good.” The prevalence of higher mental health reported in previous CCDI Quick Stats ranges from 70.8% in 2016, to 72.5% in 2015 and 71.2% in 2014.10-12

Data breakdowns

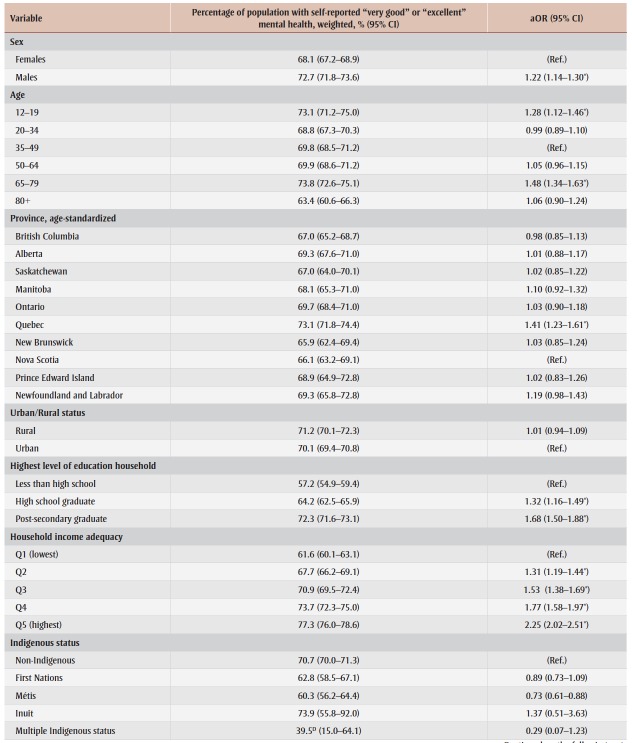

Table 2 displays the descriptive characteristics of the population in Canada with higher (“excellent” or “very good”) selfreported mental health, which can also be found in the CCDI Data Tool. We found that males aged 12 years or more had a prevalence of higher mental health of 72.7%, while females had a prevalence of 68.1%. The prevalence of higher mental health across all age groups ranged from 63.4% (80+ years) to 73.8% (65–79 years).

Table 2. Descriptive characteristics and adjusted odds ratio of population with higher self-reported mental health, age ≥12 years, Canada excluding territories.

The rates of higher mental health also varied across provinces, between 65.9% (New Brunswick) and 73.1% (Quebec). Prevalence of higher mental health was similar for individuals living in rural areas (71.2%) and those living in urban areas (70.1%).

Rates of higher mental health tended to increase with increasing education level (from 57.2% for less than high school to 72.3% for postsecondary graduate) and increasing household income adequacy (from 61.6% at Q1 to 77.3% at Q5). The prevalence of higher mental health was 73.9% among Inuit, 62.8% among First Nations peoples and 60.3% among Métis people, whereas prevalence of higher mental health was 70.7% among non- Indigenous Canadians.

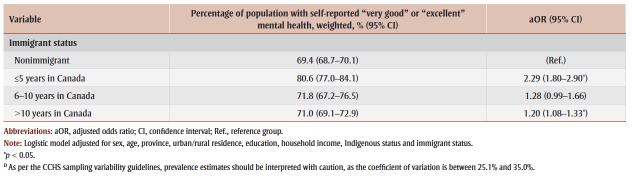

Nonimmigrants had a prevalence of higher mental health of 69.4%. Prevalence of higher mental health appeared to decrease with length of time in Canada, from 80.6% among recent immigrants (≤ 5 years in Canada) to 71.0% among those who had been in Canada for longer than 10 years.

The odds of higher self-reported mental health were 22% greater for males than for females (aOR = 1.22, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.14–1.30). Those aged 12–19 years (aOR = 1.28, 95% CI = 1.12– 1.46) and 65–79 years (aOR = 1.48, 95% CI = 1.34–1.63) had greater odds of reporting higher mental health than 35–49 year olds. There were no significant differences in odds between the 20–34, 50–64, 80+ and the 35–49 year age groups.

Quebec was the only province with a statistically significant odds ratio, with odds of higher mental health 41% greater than for Nova Scotia (aOR = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.23–1.61).

Individuals who graduated from high school or from postsecondary institutions had odds of higher mental health that were 32% (aOR = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.16– 1.49) and 68% (aOR = 1.68, 95% CI = 1.50–1.88) greater than those who did not graduate from high school. The odds of higher mental health increased in a significant, stepwise fashion with increasing income (aORQ2 = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.19–1.44; aORQ3 = 1.53, 95% CI = 1.38–1.69; aORQ4 = 1.77, 95% CI = 1.58–1.97; and aORQ5 = 2.25, 95% CI = 2.02–2.51).

No significant differences in odds of higher mental health were found by Indigenous status.

Immigrants had greater odds of higher mental health than nonimmigrants; however, the magnitude of this effect decreased with length of time in Canada (≤ 5 years: aOR = 2.29, 95% CI = 1.80–2.90; 6–10 years: aOR = 1.28, 95% CI = 0.99–1.66; > 10 years: aOR = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.08– 1.33).

Conclusion

Self-reported mental health is one of the general health indicators included in the CCDI, a resource that presents information on the surveillance of chronic conditions in Canada. Based on the logistic regression results, females 12+ years old, individuals in the 35–49 age group, individuals with less than a high school education and/or those in the lowest income quintile group would benefit from targeted mental health promotion interventions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Canadian Chronic Disease Indicators (CCDI) Steering Committee for their invaluable feedback and revision of this At-a-glance article. We also want to thank Brenda Branchard for coordinating the release of the 2019 edition of the CCDI as well as all of the analysts who updated Table 1 with the most recent prevalence estimates.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions and statement

AMB, EP, TL and MV drafted this At-aglance article. MV analyzed the prevalence estimates for self-reported mental health and conducted the logistic regression model analysis. All authors interpreted the data, and reviewed and/or revised this At-a-glance article.

The content and views expressed in this At-a-glance article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Hakulinen C, Pulkki-Raback L, et al, et al. Structural and functional aspects of social support as predictors of mental and physical health trajec¬tories: Whitehall II cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016:710–5. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-206165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg M, Poppel M, et al, et al. Visiting green space is associated with mental health and vitality: a cross-sectional study in four European cities. Health Place. 2016:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolappa K, Henderson DC, Kishore SP, et al. No physical health without men¬tal health: lessons unlearned. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91((1)):3–3A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.115063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegethoff M, Stalujanis E, Belardi A, Meinlschmidt G, et al. Chronology of onset of mental disorders and physical diseases in mental-physical comorbidity – A National Representative Survey of Adolescents. PLOS One. 2016;11((10)):e0165196–3A. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DL, Charney DS, et al. Mood disor¬ders and medical illness: a major public health problem. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54((3)):177–80. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00639-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten SB, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, Modgill G, Eliasziw M, et al. Major depression as a risk factor for chronic disease incidence: longitudinal ana¬lyses in a general population cohort. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30((5)):407–13. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Ottawa(ON): Positive Mental Health Surveillance Indicator Framework [Internet] Available from: https://infobase.phac-aspc.gc.ca/positive-mental-health/ [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Ottawa(ON): 2019–20 Departmental Plan [Internet] Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/corporate/transparency/corporate-management-reporting/reports-plans-priorities/2019-2020-report-plans-priorities/phac-aspc-2019-2020-departmental-plan-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Mawani FN, Gilmour H, et al. Validation of self-rated mental health. Health Rep. 2010;21((3)):61–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. (10) Vol. 38. Ottawa(ON): 2018. Canadian Chronic Disease Indicators, Quick Stats, 2018 Edition; pp. 385–90. [Google Scholar]

- The 2017 Canadian Chronic Disease Indicators. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2017;37((8)):248–51. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.37.8.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Chronic Disease Indicator Framework Quick Stats, 2016 edition. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2016;36((8)):248–51. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.36.8.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]