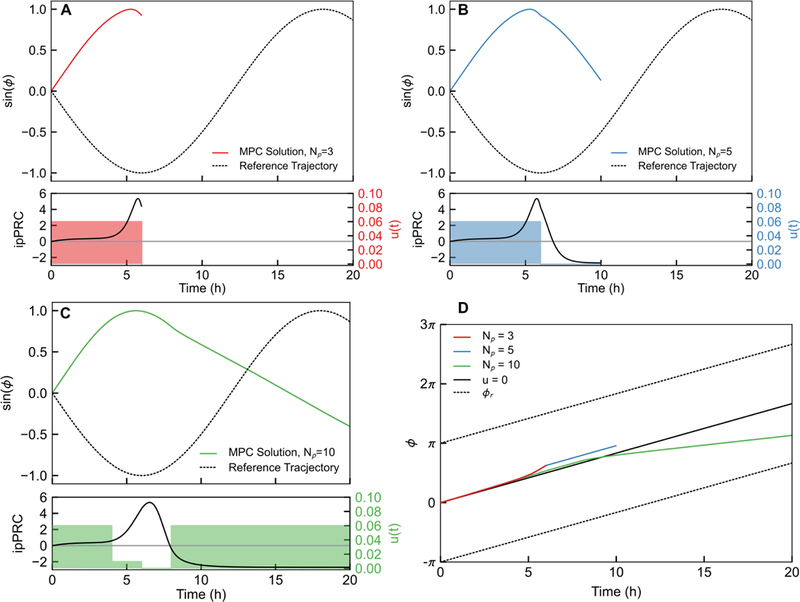

Figure 8:

Changes in the prediction horizon affect the finite-horizon optimal control trajectory based on the observable ipPRC. This is demonstrated by computing the first finite-horizon optimal control trajectory and varying that horizon. (A-C) Finite-horizon optimal control trajectories for Np = 3, 5, and 10, respectively. In all cases, τ = 2h, ∆ϕf = and ϕ0 = 0. Note that not only do the finite horizon optimal controls computed by the MPC differ, they seek to achieve the same shift by either advances (A,B) or delays (C). The in finite-horizon optimal control is achieved via delays (∆ϕf > ∆ϕ⋆), and so A or B would lead to excessively-long resetting by either selecting advances to achieve the shift, or first selecting advances then later choosing delays as in C. (D) This result is visualized by plotting the phase progression for each MPC case and for the 0-input case. Phase advances evidently yield slower progress toward the reference phase, and thus short prediction horizons choose ineffectively. This complication in MPC problem formulation may be circumvented by providing the controller with the optimal resetting direction a priori.