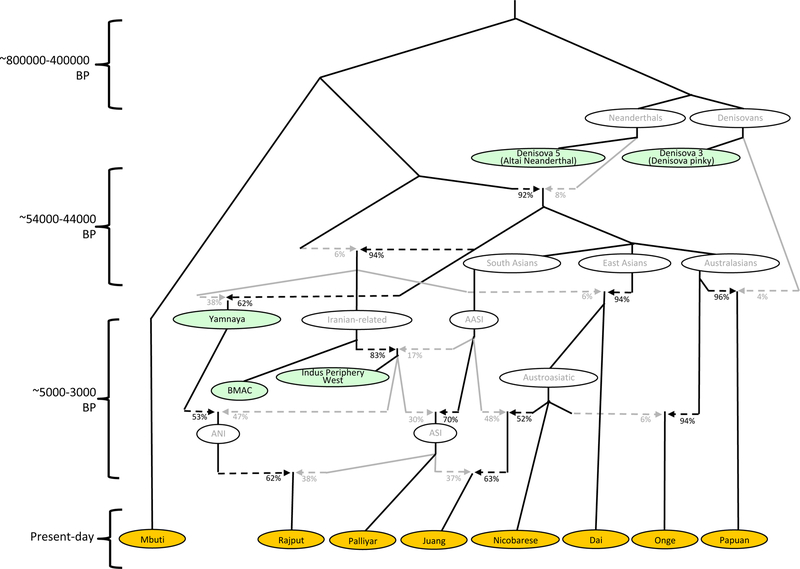

Fig. 5. Admixture Graph Model.

The largest deviation between empirical and theoretical f-statistics is |Z|=2.9, indicating a good fit considering the large number of f-statistics analyzed. Admixture events are shown as dotted lines labeled by proportions, with the minor ancestry in gray. The present-day groups are shown in orange ovals, the ancient ones in blue, and unsampled groups in white. (The ovals and admixture events are positioned according to guesses about their relative dates to help in visualization, although the dates are in no way meant to be exact.) In this graph we do not attempt to model the contribution of WSHG and Anatolian farmer-related ancestry, and thus cannot model Central_Steppe_EMBA, the proximal source of Steppe ancestry in South Asia (instead we model the Steppe ancestry in South Asia through the more distally related Yamnaya). However, the admixture graph does highlight several key findings of the study, including the deep separation of the AASI from other Eurasian lineages, and the fact that some Austroasiatic-speaking groups in South Asia (e.g. Juang) harbor ancestry from a South Asian group with a higher ratio of AASI-related to Iranian farmer-related ancestry than any groups on the Modern Indian Cline, thus revealing that groups with substantial Iranian farmer-related ancestry were not ubiquitous in peninsular South Asia in the 3rd millennium BCE when Austroasiatic languages likely spread across the subcontinent.