Abstract

Background

Chronic venous ulcer healing is a complex clinical problem that requires intervention from skilled, costly, multidisciplinary wound‐care teams. Compression therapy has been shown to help heal venous ulcers and to reduce recurrence. It is not known which interventions help people adhere to compression treatments. This review is an update of a previous Cochrane review.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of interventions designed to help people adhere to venous leg ulcer compression therapy, to improve healing and prevent recurrence after healing.

Search methods

In June 2015, for this first update, we searched: The Cochrane Wounds Specialised Register; The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library); Ovid MEDLINE; Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations); Ovid EMBASE and EBSCO CINAHL. We also searched trial registries, and reference lists of relevant publications for published and ongoing trials. There were no language or publication date restrictions.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of interventions that aim to help people with venous leg ulcers adhere to compression treatments compared with usual care, or no intervention, or another active intervention. Our main outcomes were ulcer healing, ulcer recurrence, quality of life, pain, adherence to compression therapy and number of people with adverse events.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected studies for inclusion, extracted data, assessed the risk of bias of each included trial, and assessed overall quality of evidence for the main outcomes in 'Summary of findings' tables.

Main results

One randomised controlled trial was added to this update making a total of three. One ongoing study was also identified.

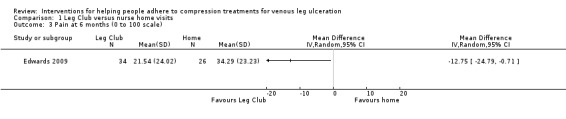

One trial (67 participants) compared a community‐based Leg Club® that provided mechanisms for peer‐support, assistance with goal setting and social interaction with home‐based care. There was no clear difference in healing rates at three months (12/28 people healed in Leg Club group versus 7/28 in home‐based care group; risk ratio (RR) 1.71, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.79 to 3.71); or six months (15/33 healed in Leg Club group versus 10/34 in home‐based care group; RR 1.55, 95% CI 0.81 to 2.93); or in quality of life outcomes at six months (MD 0.85 points, 95% CI ‐0.13 to 1.83; 0 to 10 point scale). The Leg Club may lead to a small reduction in pain at six months, that may not be clinically significant (MD ‐12.75 points, 95% CI ‐24.79, ‐0.71; 0 to 100 point scale, 15 point reduction is usually considered the minimal clinically important difference) (low quality evidence downgraded for risk of selection bias and imprecision).

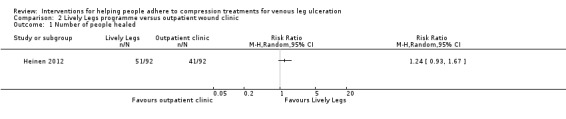

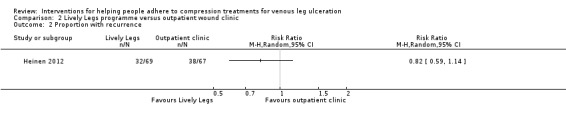

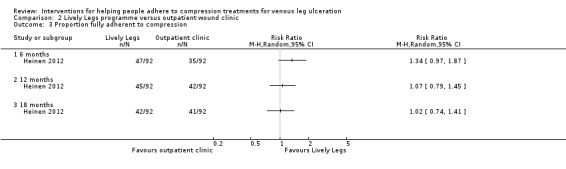

Another trial (184 participants) compared a community‐based, nurse‐led self‐management programme of six months' duration promoting physical activity (walking and leg exercises) and adherence to compression therapy via counselling and behaviour modification (Lively Legs®) with usual care in a wound clinic. At 18 months follow‐up, there were no clear differences in healing rates (51/92 healed in Lively Legs group versus 41/92 in usual care group; RR 1.24 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.67)); rates of recurrence of venous leg ulcers (32/69 with recurrence in Lively Legs group versus 38/67 in usual care group; RR 0.82 (95% CI 0.59 to 1.14)); or adherence to compression therapy (42/92 people fully adherent in Lively Legs group versus 41/92 in usual care group; RR 1.02 (95% CI 0.74 to 1.41)). The evidence from this trial was also downgraded to low quality due to risk of selection bias and imprecision.

A single study compared patient education delivered via video with education delivered by text (pamphlet). However, no outcomes relevant to this review were reported.

We found no studies that investigated other interventions to promote adherence to compression therapy.

Authors' conclusions

It is unclear whether interventions designed to help people adhere to compression therapy improve venous ulcer healing and reduce recurrence. There is a lack of trials of interventions that promote adherence to compression therapy for venous ulcers.

Plain language summary

Interventions for helping people adhere to compression treatments to aid healing of venous leg ulcers

Background

Venous leg ulcers take weeks or months to heal, cause distress, and are very costly for health services. Although compression using bandages or stockings helps healing and prevents recurrence, many people do not adhere to compression therapy. Therefore, interventions that promote the wearing of compression should improve healing and prevent recurrence of venous ulcers.

Study characteristics

This updated review (current to 22 June 2015) included three randomised controlled trials. One study conducted in Australia compared standard wound care (venous ulcer treatment, advice and support, follow‐up management and preventive care) in a community clinic called 'Leg Club' (34 participants) with the same wound care in the home by a nurse (33 participants). Another study (184 participants) compared a community‐based exercise and behaviour modification programme called 'Lively Legs' for promoting adherence with compression therapy and physical exercise plus usual care (wound care, compression bandages at an outpatient clinic) with 'usual care' alone in 11 outpatient dermatology clinics in the Netherlands. A third small study (20 participants) compared a patient educational intervention to improve knowledge of venous disease and ulcer management. The intervention was delivered via video or via written pamphlet for people attending a wound healing research clinic in Miami, USA. Participants in all studies were aged 60 or more, with a venous leg ulcer.

Key results

The Leg Club®, a community‐based clinic, did not improve healing of venous leg ulcers or quality of life any more than nurse home‐visit care, but may result in less pain after six months. Seventeen more people out of 100 were healed after participating in Leg Club (46/100 people in Leg Club healed compared with 29/100 people having usual home care); this difference was not statistically significant and could have occurred by chance. Leg Club participants rated their quality of life 0.85 points better than those receiving home care, assessed on a 10 point scale. Leg Club participants rated their pain at six months 12.75 points lower than the home care group, assessed on a 100 point scale. This trial did not report whether Leg Club clinics improve adherence to compression, time to healing, or prevent recurrence more than home care.

It is not clear whether Lively Legs®, a community‐based self‐management programme, improves ulcer healing or recurrence after 18 months compared with usual care. It is not clear whether Lively Legs® influences adherence to compression therapy. The trial did not report whether the Lively Legs self‐management programme clinics improve time to healing of ulcers, reduce pain, or improve quality of life any more than usual care in a wound clinic.

It is unclear if patient education delivered by video or via a pamphlet improves healing or recurrence, as the study did not measure any outcomes relevant to this review.

No other interventions were identified.

Quality of the evidence

It is unclear whether community‐based clinics to promote adherence to compression therapy either promote adherence or improve ulcer healing or recurrence. The available evidence is low quality due to the risk of bias in the included studies and their small sample sizes which lead to great imprecision and uncertainty. One single small trial that evaluated an education intervention failed to measure the outcomes we considered important for this review such as ulcer healing and recurrence, and adherence. Further high quality studies are likely to change the outcome of this review.

We know that compression therapy is effective, but do not know which interventions improve adherence to compression therapy.

Up‐to‐date June 2015.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Venous leg ulceration represents the most prevalent form of difficult to heal wounds, and these problematic wounds require a significant amount of health care resources for their treatment. Typically, venous leg ulceration is a chronic, relapsing condition (de Araujo 2003). The most common cause of venous leg ulceration is venous insufficiency, which accounts for nearly 80% of all ulcers. People with chronic venous insufficiency are prone to development of venous leg ulcers on the ankles and legs. A venous leg ulcer can be defined as 'an open sore in the skin of the lower leg due to high pressure of the blood in the leg veins' (British Association of Dermatologists 2010). By definition, chronic venous ulcers are defects in the skin, usually below the knee, that have been present for more than four to six weeks (Walker 2002). Ulcers of long duration and greater size are known to be markers of a poor prognosis (Margolis 2004). They are typically painful and heal slowly, resulting in an impaired quality of life, social isolation and reduced work productivity (Persoon 2004; Vowden 2009).

Venous leg ulcers are the most common cause of lower limb ulceration in the western world, with prevalence estimated to be 1% in the adult population and reported to be as high as 3% in adults aged 65 and over (Donnelly 2009) with a higher incidence in women than men (ratio 1.25:1) (Henke 2010; Margolis 2002). Some prevalence estimates have been as high as 4.3% (Baker 1991; Margolis 2002; Moffatt 2007; Stacey 2001; Vowden 2009). These variations can probably be explained by the different survey and sampling methods used (e.g. whether only those people whose ulcers are known to health services are identified, and whether case validation is employed).There are several underlying pathologies associated with leg ulceration, including venous, arterial and rheumatoid disease, and ulcers may occur in the presence of one, or a combination, of underlying conditions (Baker 1992; Henke 2010).

This review focuses on venous leg ulcers that occur when damage to the deep, or superficial veins, or both (e.g. from a thrombosis) result in a high ambulatory venous pressure; the communicating veins between the superficial veins may also be incompetent. The high venous pressure is thought to cause leakage in the associated capillaries, with the resultant deposition of red blood cells and other protein molecules that cause fibrosis and staining of the subcutaneous tissue and skin, which leads to relative ischaemia (lack of oxygen), poor nutrition of the surrounding tissues, and breakdown of the skin.

Despite improvements in treatments for venous ulcers and the widespread introduction of compression bandaging as the mainstay of current conservative management, a significant proportion of venous leg ulcers remain unhealed or recur after a period of time. At least 28% of people affected by this will experience more than ten episodes of ulceration in their lifetimes, with recurrence rates estimated at between 45% and 87% and up to 20% of leg ulcers being active at any point in time (Abbade 2005; Nelson 2006; Vowden 2006). Reasons for variable healing and recurrence rates are multifactorial. Early diagnosis and treatment are important, although patient adherence to compression treatment is also an important factor, not just for healing but also for preventing recurrence.

Current treatments for venous ulcers

Venous leg ulcers that have been present for a prolonged period of time pose a substantial management challenge for clinicians (Simon 2004). Treatments that are used to heal and prevent recurrence of venous ulcers include compression, local wound care, surgery, physical therapy, systemic (whole body) drug treatments and attendance at community clinics for leg ulcer care. Management guidelines have identified compression therapy as the cornerstone in the treatment of venous leg ulcers (Cullum 2001; Nelson 2012; O'Meara 2012), and, in view of the high rate of recurrence, compression hosiery is also current standard practice for the prevention of recurrence (Nelson 2012).

We know from previous Cochrane reviews that compression increases ulcer healing rates when compared with no compression (O'Meara 2012); that adherence to high levels of compression after healing reduces the rate of recurrence (Nelson 2012); that multi‐component systems are more effective than single‐component systems, and that multi‐component systems containing an elastic bandage are more effective than those containing mainly inelastic bandages (O'Meara 2012). Compression acts by reducing the abnormally high pressure seen in the superficial veins, and reduces lower limb swelling and oedema.

The efficacy of compression therapy depends mainly upon exerted pressure and stiffness of the bandage (Partsch 2006). Lowest recurrence rates are reported in people who are treated with the highest degree of compression, and it is recommended that people wear the highest level of compression that is comfortable (Nelson 2012); but it is also reported that many patients cannot tolerate, or do not adhere to, compression bandaging therapy (Bale 2003).

Adherence can be defined as the extent to which patients follow the instructions they are given for treatments (Haynes 2008). The term, adherence, is intended to be non‐judgemental, a statement of fact rather than of blame attributable to the patient, prescriber, or compression treatment. Adherence rates are influenced by people's beliefs about how worthwhile the treatment is (Jull 2004). There is a need for better understanding of the methods that might improve adherence to inform clinical practice, and to improve healing rates and reduce recurrence of venous ulcers.

Description of the intervention

Educational interventions, support group interventions, nursing and medical interventions, multidisciplinary interventions and healthcare system interventions, either alone, or in combination may improve adherence. Community models of care, which include 'leg clubs', offer a setting where people with similar problems can socialise in a supportive, information‐sharing environment (Brooks 2004; Edwards 2005a). Leg clubs provide a room or space for social activities and refreshments, and separate areas where wound care is provided at 'dressing stations' where participants are still able to communicate with each other. Healthcare system interventions such as educational programs that may include a combination of cognitive, behavioural or affective components, or both, may also improve adherence to compression therapy (Van Hecke 2008; Van Hecke 2009). Specific interventions may comprise verbal instruction, written instruction, or both, as well as counselling about the patient's underlying disease, the importance of compression therapy and adherence to therapy.

Another model, 'Lively Legs' provides counselling sessions in an outpatient setting. The programme provides evaluation of patient lifestyle and heath beliefs; identification of barriers and facilitators for behaviour change; and education materials. The aim of the programme is to encourage behaviour change to promote adherence to exercise and compression treatment (Heinen 2012).

How the intervention might work

There is little evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) about adherence rates to compression therapy, or patients' views. There is some suggestion that nursing interventions result in the patient 'more consciously following advice', including performing exercise and wearing compression bandages; it is assumed that adherence to the gold‐standard of compression treatment results in improved healing (Van Hecke 2011). Another study indicates that patients do not adhere to compression treatments due to pain, discomfort and lack of valid lifestyle advice (Van Hecke 2009). Interventions designed to increase adherence to wearing compression bandages should improve healing and recurrence rates for people with chronic venous ulcers.

Why it is important to do this review

Chronic venous ulcer healing remains a complex clinical situation and often requires the intervention of skilled, but costly, multidisciplinary wound care teams. Recurrence is often an ongoing issue for people who experience venous ulcers. If the gold‐standard of treatment (compression) is adhered to, we believe that healing rates will improve. It would be useful to know which interventions help people adhere to compression treatments to heal ulcers and to prevent recurrence.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of interventions designed to help people adhere to venous leg ulcer compression therapy, and thus improve healing of venous leg ulcers and prevent recurrence of leg ulcers after healing.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), or cluster‐randomised controlled trials (cluster‐RCTs) of interventions designed to improve adherence with compression therapies.

Types of participants

Adults (as defined in trials) undergoing treatment for venous leg ulceration or prevention of recurrence of venous leg ulcers.

Types of interventions

We included studies that assessed interventions designed to help people adhere to compression treatments for venous leg ulceration and prevention of recurrence. The study had to state that the aim of the intervention was to increase adherence to compression treatments for the study to be eligible (regardless of whether adherence was reported as an outcome). We searched for any type of intervention including educational interventions, support group interventions, nursing and medical interventions, multidisciplinary interventions and healthcare system interventions either alone or in combination aimed at people with venous leg ulcers.

All possible comparison interventions were eligible for inclusion. These included sham or control intervention, usual care or no intervention, one intervention compared with another, or single interventions compared with complex interventions. We excluded trials designed to assess knowledge of caregivers, topical dressings used as adjunct to compression and trials of compression bandages only, as these are topics of other reviews.

Types of outcome measures

We included outcomes at all time points.

Primary outcomes

Since adherence to compression treatment should result in more rapid healing of venous ulcers and a reduced rate of recurrence, the primary outcomes considered for this review were:

venous ulcer healing (e.g. proportion of ulcers healed within trial period, as defined by the trial authors);

time to complete healing;

recurrence of venous ulcer (as reported in the trials);

adherence to compression therapy, e.g. proportion reporting adherence to compression.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes considered for this review included:

quality of Life (QoL);

adverse events;

pain;

economic outcomes.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

In June 2015 we updated the searches of the following electronic databases to find reports of relevant randomised clinical trials:

The Cochrane Wounds Specialised Register (searched 22 June 2015)

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 5);

Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to 22 June 2015);

Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, (searched 22 June 2015);

Ovid EMBASE (1974 to 22 June 2015);

EBSCO CINAHL (1982 to 23 June 2015).

The search strategies used for these databases can be found in Appendix 1. The Ovid MEDLINE search was combined with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision maximizing version (2008 revision) (Lefebvre 2011). The Ovid EMBASE and Ovid CINAHL searches were combined with the trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN 2015). There were no restrictions with respect to language, date of publication or study setting.

We also searched the following trial registries:

The Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au/);

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/);

The World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal (www.who.int/trialsearch);

ISRCTN registry (www.controlled‐trials.com/).

Searching other resources

The bibliographies of all studies eligible for inclusion identified by the above strategies were searched for further studies not identified through searches of electronic databases.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (CW, RJ) independently assessed the titles and available abstracts of all studies identified by the initial search, excluded any clearly irrelevant studies, and assessed full copies of reports of potentially eligible studies using the inclusion criteria. The authors resolved disagreements regarding inclusion by consensus.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (CW, RJ) independently extracted data from the included trials on source of funding, study population, interventions, analyses and outcomes, using standardised data extraction forms. We contacted trial authors, as required, to obtain more information.

In order to assess efficacy, we extracted raw data for outcomes of interest (means and standard deviations for continuous outcomes, number of events for dichotomous outcomes, and hazard ratio and 95% confidence intervals for time‐to‐event data) where available in the published reports. We also recorded wherever reported data were converted or imputed in the notes section of the Characteristics of included studies table.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias of each included trial against key criteria recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins 2011), namely:

random sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors;

incomplete outcome data;

selective outcome reporting; and

other sources of bias (such as whether groups were similar at baseline for important prognostic indicators, such as wound size and severity, and duration of ulcer; and whether co‐interventions were avoided, or similar, within the treatment and control groups).

We judged each of these criteria as low risk of bias, high risk of bias, or unclear (due to either a lack of information or uncertainty over the potential for bias), and also gave an overall impression of the risk of bias for the entire study, based on the judgement that an unclear or high risk of bias for one or more key criteria weakens our confidence in the estimate of effect (Higgins 2011). This meant that if any of the above criteria were rated as having a high or unclear risk of bias individually, we assigned the trial a high risk of bias overall. We assigned a trial a low risk of bias overall only if all of the above criteria were judged to be at low risk of bias individually.

Review authors resolved disagreements by consensus, and consulted a third review author to resolve disagreements, if necessary.

Measures of treatment effect

The results of the included studies were plotted as point estimates, that is, relative risks (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous outcomes, and mean difference (MD) and 95% CI for continuous outcomes. We planned to extract hazard ratio (HR) data for time to healing, but this was not reported by any study.

Unit of analysis issues

For trials presenting outcomes at multiple time points, we extracted data at all time points (three months, six months, 12 months, 18 months), as subgroups.

Dealing with missing data

If data were missing from the trial reports, we contacted trial authors to try to obtain the relevant information.

We used number randomised as the denominator for dichotomous outcomes that assessed a benefit (healing, adherence), on the assumption that any participants missing at the end of treatment did not have a positive outcome (e.g. for healing, we would have assumed that missing participants did not have a healed ulcer). We used number available at follow‐up as the denominator for dichotomous outcomes that assessed a harm, and data as available to analyse continuous outcomes.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We had planned to assess statistical heterogeneity by Q test (chi‐square) and I2 and to interpret a chi‐square test resulting in a p‐value <0.10 as indicating significant statistical heterogeneity. In order to assess and quantify the possible magnitude of inconsistency (i.e. heterogeneity) across studies, we had planned to use the I2 statistic with a rough guide for interpretation as follows: 0% to 40% might not be important; 30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100% considerable heterogeneity and likely unsuitable for meta‐analysis (Deeks 2011). The trials we included reported different interventions, comparators and outcomes, so statistical heterogeneity was not assessed.

Assessment of reporting biases

We had planned to assess publication bias by constructing funnel plots if at least 10 studies are available for the meta analysis of a primary outcome, but this was not possible, as we had too few included studies.

Data synthesis

Outcomes were presented in forest plots. For clinically homogeneous studies, with similar participants, comparators, and using the same outcome measure, we had planned to pool outcomes in a meta‐analysis. We planned to use a fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis, but in the presence of heterogeneity that may have been important (I2 of 40% or more) we would have used a random effects model as a sensitivity analysis to see if the conclusions differed, and presented the results from the random effects model. For time‐to‐event data, estimates of hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI if presented in the trial reports, would have been converted into the log rank observed minus expected events and variance of the log rank, and these estimates would be pooled using a fixed effect model (as only a fixed‐effect model is available in RevMan for this analysis) (Deeks 2011). However, meta‐analysis was precluded because the trials reported different interventions, comparators and outcomes.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If there were sufficient data (e.g. stratified data presented in the trials), we planned to perform separate subgroup analyses to determine whether healing is influenced by the following factors:

severity of ulcers at baseline determined by size (>5cm 2 or ≤5cm 2)) or ulcer duration (>6months or ≤ 6 months) at baseline;

different geographical locations/settings (rural versus urban);

community versus home care; and

specialist multidisciplinary clinic versus nurse led clinic.

We anticipated that trials may have presented outcomes by baseline severity and duration of ulcers. The other analyses may have come from data from separate trials. We had planned to informally compare the magnitudes of effect to assess possible differences in response to treatment between the two groups. The magnitude of the effects can be compared between the subgroups by assessing the overlap of the confidence intervals. Non‐overlap of the confidence intervals indicates statistical significance (Deeks 2011).

As there were insufficient data, we did not perform our planned subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

We had planned sensitivity analyses to investigate the robustness of the treatment effect to allocation concealment by removing the trials that did not report adequate allocation concealment (i.e. inadequate or unclear) from the meta‐analysis to see if this changed the overall treatment effect. Then we had planned using the same method to assess the effect of excluding trials with unblinded or unclear outcome assessment.

We had also planned sensitivity analysis to investigate the effect of imputation of missing data, but as we did not impute any data, the analysis was not done.

We had insufficient data for these analyses.

Presentation of results

The main results of the review were presented in 'Summary of findings' tables which provide key information concerning the quality of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data on the main outcomes, as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration (Schunemann 2011a), using GRADEpro software. We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of evidence Schunemann 2011b.

After the protocol was published, we decided to include the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables: number of people with ulcers healed, recurrence of ulcers, time to complete healing, quality of life, pain, adherence to compression, and number of people with adverse events. Quality of life was reported using two different instruments; we decided to present only the data measured using the more widely accepted measure (SF12).

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies

Results of the search

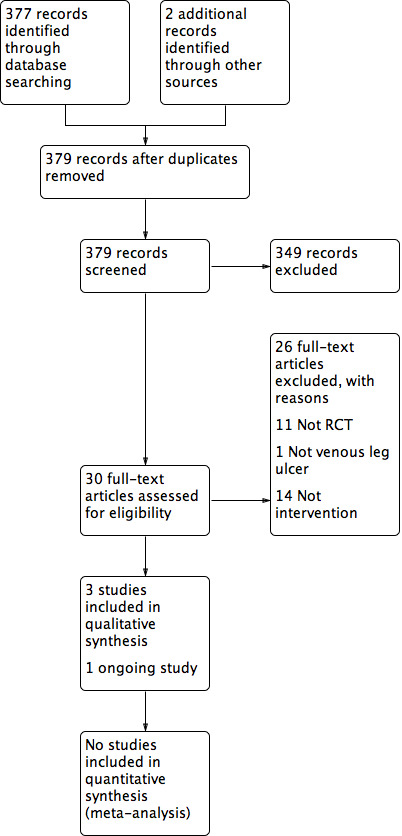

The original search of the Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL yielded 322 titles and abstracts, and the updated search, conducted from 2013 to 22 June 2015 yielded an additional 55 citations. A handsearch found two additional records through other sources (Figure 1). Thus, we screened 379 citations in total, and after initial review, we excluded 349 because they were either not RCTs, involved another patient population (e.g. diabetic foot ulcers) or did not evaluate interventions to help adherence to compression therapy. After screening of titles and abstracts, we identified 30 trial reports for full text assessment. Three studies met the inclusion criteria: two included in the first review (Edwards 2009, Heinen 2012) and one new trial (Baquerizo Nole 2015) . We also identified one ongoing study (O'Brien 2014).

1.

Study flow diagram of the number of records identified, included and excluded, and the reasons for exclusions

Included studies

Details of each of the included studies are summarised in the Table of Characteristics of included studies.

Baquerizo Nole 2015 reported a single‐centre parallel RCT (20 participants) investigating the effectiveness of two educational tools (consisting of either video or written pamphlet) to improve knowledge of venous disease and ulcer management of patients attending a wound healing research clinic in Miami, USA. The educational information in both formats was identical.

Edwards 2009 reported a single‐centre parallel RCT (67 participants) that evaluated the effectiveness of standard wound care (consisting of health assessment and referral as indicated, venous ulcer treatment based 'protocols', advice and support, follow‐up management and preventive care) in a community clinic called 'Leg Club' (34 participants) compared with the same wound care in the home by a nurse (33 participants) conducted in Queensland, Australia. Three published interim analyses of this trial were identified (Edwards 2005a; Edwards 2005b; Edwards 2005c).

Heinen 2012 reported a multi‐centre RCT (184 participants) investigating the effectiveness of a community‐based exercise and behaviour modification programme called 'Lively Legs' for promoting adherence with ambulant compression therapy and physical exercise (92 participants), plus usual care (wound care, compression bandages at an outpatient clinic) compared with 'usual care' alone (92 participants), conducted in 11 outpatient dermatology clinics in the Netherlands.

Participants

All twenty participants included in Baquerizo Nole 2015 were over 60 years old. Non‐Hispanic men made up the majority of the study sample. Intervention and control groups did not differ significantly for education level, occupation, number of current ulcers, number of lifetime ulcer episodes, baseline pain and use of compression stockings. Most participants had one or two ulcers at enrolment (70% in the intervention group and 50% in the control group). Ulcer size was not reported. Twenty percent of participants in the intervention group and 30% in the control group had an ulcer for less than 6 months, while more participants had ulcers for more than 6 months (70% in the intervention group and 60% in the control group). Mean (SD) pain on a 0 to 10 point scale (where 0 is no pain) was 3.3(2.8) points in the intervention group and 3.5 (3.9) points in the control group. The presence of co‐morbidities was not reported. The use of compression therapy seemed suboptimal: 43% in the intervention group and 29% in the control group.

Most participants included in Edwards 2009 (90%) were aged over 60 years. Men made up 54% of the study sample, and 60% required some form of aid to mobilise. Intervention and control groups did not differ significantly for presence of co‐morbidities such as cardiovascular disease, osteoarthritis and history of varicose veins, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and previous venous surgery. The average ulcer size area was reported to be 7.5 cm2 (1.0 cm2 to 140.0 cm2) and the median duration of ulcer was reported as being 22 weeks (four to 180 weeks).

The mean age of participants included in Heinen 2012 was 66 years (27 to 91 years). Women made up 60% of the study sample. Intervention and control groups did not differ significantly for presence of varicosities, diabetes and claudication (pain after walking a short distance). The intervention group included a higher number of participants with hypertension (43% versus 30%) and smoking (22% versus 15%). The control group included a higher number of participants with previous DVT (40% versus 27%), heart failure (23% versus 17%) and arthritis (27% versus 20%).The average ulcer size in the intervention group was reported to be 9 cm2 (0.2 cm2 to 180 cm2) and the mean duration was reported to be seven months (0.3 to 54 months). The average ulcer size in the control group was reported to be 8.4 cm2 (0.4 cm2 to 130 cm2) and the mean duration was reported to be 7.3 months (0.8 to 54 months).

Interventions

The trial by Baquerizo Nole 2015 used an educational intervention designed to improve patient knowledge about VLU disease and its management delivered by video to the intervention group, compared to a control group who received the same information in text form (written pamphlet). Participants were instructed to complete a baseline test with 15 questions about venous leg ulcer pathophysiology, management and lifestyle with an emphasis on compression therapy and reasons to seek care between visits to assess their knowledge. Characteristics of the educational intervention were not reported.

The Edwards 2009 trial's Leg Club settings consisted of a room or space for social activities and refreshments, and separate areas where wound care was provided at 'dressing stations' where participants were still able to communicate with each other. Both the Leg Club and control groups received nursing care for up to six months consisting of: comprehensive assessment including Ankle Brachial Pressure Index (ABPI); referral for further circulatory assessment as indicated; venous ulcer treatment based on research protocols; advice and support about venous leg ulcers; and follow‐up management and preventive care. These five care items were delivered weekly by community nurses to the intervention group at a Leg Club where participants had opportunities for peer‐support, assistance with goal setting and social interaction, and delivered during individual home visits by community nurses to participants in the control group. Although not stated explicitly in this trial report, Leg Clubs have been established to improve adherence to compression therapy by providing holistic care for patients in a supportive environment (Lindsay 2001).

In the Heinen 2012 trial, the 'Lively Legs programme' intervention group received the following interventions in addition to the usual care delivered in the control group: Lively Legs counselling sessions (up to six) that included evaluation of patient lifestyle; health education related to patient heath beliefs; motivation for increasing exercise; other barriers and facilitators for behaviour change; and goal setting on one or more lifestyle topics. The outpatient clinic was the setting for Lively Legs counselling, the session time varied from 45 to 60 minutes for the first session to 20 to 30 minutes for subsequent sessions. Where possible an informal caretaker was present at each session.

Outcomes

Baquerizo Nole 2015 measured knowledge of venous leg ulcer pathophysiology, management and lifestyle, compression therapy and reasons to seek care between visits at baseline, immediately after the intervention and four weeks later, using a test. Outcomes relevant to this review were not reported. The questionnaire used to assess knowledge was administered prior to the educational intervention at baseline, post educational intervention [administered immediately after the intervention] (posttest) and four weeks later (4 week posttest). The development, validity and reliability of the questionnaire and how it was administered was not reported. The setting or time allocated for education sessions was not reported. The type of personnel who administered the test was not reported.

Edwards 2009 reported outcomes at baseline, 12 and 24 weeks. We included the following outcomes in this review: proportion of participants with ulcers healed, pain and quality of life. Edwards 2009 also reported economic outcomes on a subset of 56 participants (out of a total of 67) (Gordon 2006), but as the authors did not report the effect estimate used in the analysis clearly, we were unable to extract and verify the cost‐effectiveness estimates.

Heinen 2012 reported outcomes at baseline, six months, 12 months and 18 months. We included the following outcomes in this review: the number of people healed, the number of people with recurrence, the number of people adherent to compression therapy.

Excluded studies

We excluded 26 studies, as they were not RCTs (11 studies), they did not include interventions to help people with venous leg ulcers adhere to compression therapy (14 studies), or did not include people with venous leg ulcers (one study) (see Table of Characteristics of excluded studies).

Ongoing studies

We identified one ongoing study (O'Brien 2014), which compares a self‐management telephone based intervention plus usual care with usual care alone for promoting exercise and healing rates for adults with venous leg ulcers.

The self‐management exercise intervention consists of a 12 week home‐based unsupervised progressive resistance exercise program, aimed at strengthening the calf muscle of the leg, given in addition to usual care (compression bandaging and wound care). The programme is administered by telephone calls from the principal researcher at 4 timepoints (Week 1, 3, 6 and 9) over the 12‐week intervention. Participants will also be encouraged to walk at least three times per week for 30 minutes. Outcomes are healing rates, ankle range of motion, self‐reported and objective measures of physical activity, and self‐reported adherence to the self‐management programme. Trial recruitment is complete, but no results were available at the time of publication.

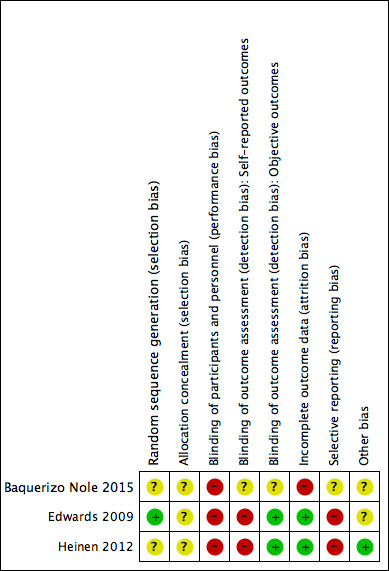

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, the risk of bias in Baquerizo Nole 2015 was high. The study was at risk of selection, performance, detection and attrition biases due to poor reporting. The authors did not report the randomisation method or if treatment allocation was concealed. Performance and detection biases were likely, due to the lack of blinding of participants, investigators and outcomes assessors.

Attrition bias was likely. The study included only 10 participants per group and as three participants were lost to follow‐up from one group, this may have led to biased results. It is unclear if there were reporting biases as the authors did not report important patient‐relevant outcomes including ulcer healing and recurrence. However the authors indicate in written correspondence that they only planned to measure knowledge.

It is unclear if there were other biases, such as baseline differences or co‐intervention differences between treatment groups, due to lack of reporting.

The risk of bias in Edwards 2009 was high. The authors used a random number program to generate the random sequence, but did not report whether allocation was concealed, therefore, it is unclear whether selection bias was avoided. Performance bias was likely, due to the difficulty of blinding participants and investigators. As participants were aware of their treatment group, self‐reported outcomes pain, and quality of life may be susceptible to detection bias. However, complete healing, as defined by the trial authors ('full epithelialisation lasting for two weeks'), and presumably assessed by the community nurse, seemed objective, and less susceptible to detection bias (Figure 2).

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

The proportion of participants lost to follow‐up was quite high in both treatment groups (23% from the intervention group, 21% from the control group). However, as the proportion and reasons for the losses were similar in both groups, the risk of attrition bias was low.

The study was probably subject to reporting bias, as the pilot study reported that ulcer recurrence, and new ulcers were measured (Edwards 2005a), but these data were not reported in the results paper. Furthermore, the instrument used to assess pain was changed during the course of the trial .

It was unclear whether Edwards 2009 was free from other biases because the trialists used sequential estimation rather than an a priori sample size calculation. Sequential estimation is used when the sample size is not fixed in advance. Instead, data are evaluated as they are collected, and further sampling is stopped in accordance with a pre‐defined stopping rule as soon as significant results are observed.

The risk of bias was also high in Heinen 2012. It was unclear whether selection bias was avoided, as the method of randomisation or allocation to treatment was not clearly described. Performance bias was likely, as participants and investigators were probably aware of the intervention group. Detection bias was unlikely for assessment of objective outcomes (healing and recurrence), but was possible in the assessment of the self‐reported outcome (adherence). Attrition bias was unlikely, as the losses to follow‐up were even across treatment groups (see Figure 2). Reporting bias was likely, as time to time to leg ulcer recurrence was measured, but reported as time until 25% of participants had recurrence. Similary, exercise was measured as a continuous scale but reported as a dichotomised scale. There were no other biases: groups were similar at baseline and co‐interventions did not differ between groups.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Leg Club compared with nurse home visits.

| Leg Club compared to nurse home visits | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with venous leg ulcers Settings: community Intervention: Leg Club Comparison: nurse home visits | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Leg Club | ||||||

| Number of people healed Follow‐up: 6 months | 294 per 1000 | 456 per 1000 (238 to 862) | RR 1.55 (0.81 to 2.93) | 67 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

| Recurrence of ulcers ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Recurrence was probably measured but not reported |

| Time to healing ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Time to healing was probably measured but was not reported |

| Adverse events ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not measured. |

| Quality of life Spitzer's quality of life index. Scale from 0‐10. Follow‐up: 6 months | The mean quality of life score in the control group was 8.11 | The mean quality of life score in the intervention groups was 0.85 higher (0.13 lower to 1.83 higher) | 52 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| Adherence to compression ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | ||

| Pain Medical Outcomes Study Pain Measures. Scale from: 0 to 100. Follow‐up: 6 months | The mean pain score in the control group was 34.29 | The mean pain in the intervention groups was 12.75 lower (24.79 to 0.71 lower) | 60 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | A 15 point difference is usually regarded as the minimum difference that is clinically important | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Trialists failed to conceal allocation and may have performed an unplanned interim data analysis 2 Low number of participants therefore wide confidence intervals

Summary of findings 2. Lively Legs programme compared with wounds outpatient clinic.

| Lively Legs programme versus outpatient wound clinic | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with venous leg ulcers

Settings: community

Intervention: Lively Legs programme Comparison: wounds outpatient clinic | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Lively Legs programme versus outpatient wound clinic | |||||

| Time to healing ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported |

| Number of people healed Follow‐up: 18 months | 45 per 100 | 55 per 100 (41 to 74) | RR 1.24 (0.93 to 1.67) | 184 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

| Adverse events ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Adverse events were not reported, unclear if measured |

| Recurrence of ulcers Follow‐up: 18 months | 57 per 100 | 47 per 100 (33 to 65) | RR 0.82 (0.59 to 1.14) | 136 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

| Quality of life ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported |

| Adherence to compression Follow‐up: 18 months | 45 per 100 | 45 per 100 (31 to 66) | RR 1.02 (0.74 to 1.41) | 184 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

| Pain ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not measured |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Trialists failed to report randomisation method and allocation concealment 2 Low number of participants; 95% confidence interval includes both no effect and appreciable benefit

Summary of findings 3. Video education versus written education.

| Video education compared with written education for venous leg ulcers | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with venous leg ulcers Settings: community Intervention: video education Comparison: written education (pamphlet) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Written education | Video education | |||||

| Number of people healed ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Healing not reported1 |

|

Proportion with recurrence ‐ not reported |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Recurrence not reported |

| Adherence to compression ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Adherence not reported |

|

Quality of life ‐ not reported |

See comment | See comment | ‐ | See comment | Quality of life not reported | |

|

Pain at 6 months ‐ not reported |

See comment | See comment | ‐ | See comment | Pain not reported | |

| Adverse events ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Adverse events not reported |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Patient knowledge of venous leg ulcer disease and management was the only reported outcome in this study.

The interventions that were studied in the two trials that reported relevant outcomes for this review were too heterogenous to allow pooling of outcomes data. While they were both community‐based nurse‐led clinics, Leg Club® emphasised socialisation, peer‐support and patient‐empowerment, while Lively Legs promoted exercise adherence and behaviour modification. We therefore report the trial results for each trial separately. The third trial did not report outcomes relevant for this review.

Wound care in a community‐based socialisation and peer‐support clinic (Leg Club®) compared with wound care at home by nurse visits (one trial)

Number of people healed

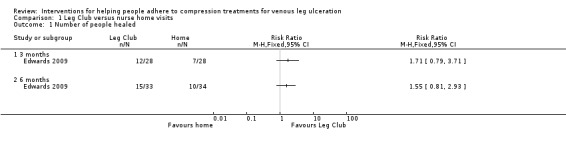

The proportion of participants healed at three months is higher in the Leg Club group (12/28, 43%) than in the home visit group (7/28, 25%), relative risk (RR) 1.71 (95% confidence intervals (CI) 0.79 to 3.71; Analysis 1.1), due to imprecision around the results, and risk of bias (low quality evidence). For the same reasons, it is uncertain if the proportion of participants healed at six months is different between treatment groups (Leg Club: 15/33 (45%), home visit group 10/34 (29%), RR 1.55, 95% CI 0.81 to 2.93; Analysis 1.1). The larger denominator at six months was from the completed study; the three month outcome data were from an interim analysis (Edwards 2005b).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Leg Club versus nurse home visits, Outcome 1 Number of people healed.

Time to complete healing

Outcome not reported.

Recurrence of venous ulcer

No report on recurrence rates or follow‐up once healing occurred.

Adherence to compression therapy

Outcome not reported.

Quality of life

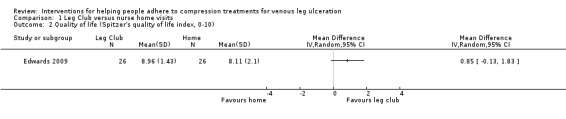

Mean quality of life measured by the 10‐point Spitzer's index was 8.96 points (standard deviation (SD) 1.43) in the Leg Club group, and 8.11(SD 2.1). It is uncertain if this differs between groups (MD 0.85 points on 10 point scale, 95% CI ‐0.13 to 1.83; Analysis 1.2), due to the potential for selection bias and the small number of participants. Edwards 2009 however reported this was statistically different using a 'triangular test of difference between means' with a P value of 0.014.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Leg Club versus nurse home visits, Outcome 2 Quality of life (Spitzer's quality of life index, 0‐10).

Adverse events

Outcome not reported.

Pain

The Edwards 2009 trial used two different outcome measurement tools to assess pain. At 12 weeks the trialists measured pain with the RAND instrument, a 36‐item heath survey, and at 24 weeks with the Medical Outcomes Study pain measure, a 100‐point continuous scale. We extracted the 24‐week data, and found there may be a small decrease in pain intensity in the participants attending the Leg Club compared with home visit care (MD ‐12.75 points on 100 point scale, 95% CI ‐24.79 to ‐0.71; Analysis 1.3. However, there is some uncertainty around this estimate due low quality evidence (downgraded for possible risk of bias and imprecision).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Leg Club versus nurse home visits, Outcome 3 Pain at 6 months (0 to 100 scale).

Economic outcomes

Edwards 2009 reported economic outcomes on a subset of 56 participants (out of a total of 67) (Gordon 2006). The incremental cost per healed ulcer to the service provider, carers, clients and community of the Leg Club was reported as AUD 515 at six months (the cost of usual care was estimated as AUD 1546). However, the paper did not report the effect estimate used in the analysis clearly (we are uncertain if there is a difference in the number of people healed (Analysis 1.1)), and thus, we were unable to verify the cost‐effectiveness estimates.

Community‐based exercise and behaviour modification clinic (Lively Legs®) plus usual care compared with usual care alone (one trial)

One trial with 184 participants compared community‐based exercise and behaviour modification (Lively Legs) plus usual care (wound care, compression bandages at an outpatient clinic) with usual care alone (Heinen 2012).

Number of people healed

It was uncertain at 18 months if there was a difference in the number of people healed between treatment groups, 51/92 healed in Lively Legs group versus 41/92 in usual care group (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.67; Analysis 2.1), due to possible imprecision around the results and risk of selection bias (low quality evidence).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Lively Legs programme versus outpatient wound clinic, Outcome 1 Number of people healed.

Time to complete healing

Outcome not reported.

Recurrence of venous ulcer

At 18 months it was uncertain if there was a difference in the number of people with recurrent ulcers between treatment groups, 32/69 with recurrence in Lively Legs group versus 38/67 in usual care group (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.14; Analysis 2.2), due to possible imprecision around the results and risk of selection bias (low quality evidence).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Lively Legs programme versus outpatient wound clinic, Outcome 2 Proportion with recurrence.

Adherence to compression therapy

Adherence with compression therapy was assessed via 6‐item questionnaire, and scored as a categorical scale: fully adherent (wore stocking always, all day); semi‐adherent (wore stocking sometimes); non‐adherence (occasionally wore stocking‐ but this was not clearly defined, or did not wear stocking). We extracted the proportion fully adherent (wore stocking always, all day). It is uncertain if there was a difference in the number people who fully adhered to compression therapy at 6 months (47/92 in Lively Legs versus 35/92 in outpatient clinic; RR 1.34, 95% CI (0.97, 1.87)); 12 months (45/92 Lively Legs versus 42/92 outpatient clinic; RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.45)); and 18 months (42/92 Lively Legs versus 41/92 outpatient clinic; RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.41)) (Analysis 2.3), due to the low quality evidence (downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision). The review authors’ estimated measures of effect for adherence were extrapolated from percentage values presented in the trial report (raw data not available), assuming that the denominators were patients as randomised.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Lively Legs programme versus outpatient wound clinic, Outcome 3 Proportion fully adherent to compression.

Quality of life

Outcome not reported.

Adverse events

Outcome not reported.

Pain

Outcome not reported.

Economic outcomes

Outcome not reported.

Educational intervention: video compared with written information

None of our pre‐specified outcomes (number healed, time to healing, recurrence, adherence, quality of life, adverse events, pain, economic outcomes) were reported in the single trial that compared an educational intervention delivered by video with the same intervention delivered in a pamphlet.

Baquerizo Nole 2015 (20 participants) reported initial and sustained improvement in knowledge of venous leg ulcer pathophysiology, management and lifestyle, compression therapy and reasons to seek care between visits. The authors reported no significant difference between groups post education intervention, but reported that male gender was associated with a significantly higher score (posttest p =0.033). However, we were unable to substantiate any difference in gender association or knowledge gain from intervention as group means and standard deviations were missing.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Low quality evidence from one trial indicates that a community‐based nursing clinic emphasising socialisation and peer‐support (Leg Club) did not improve healing rates, or quality of life, any more than home‐based visits for people with venous leg ulcers, but there was a small, though clinically insignificant, reduction in pain. The evidence from this trial was downgraded to low quality due to potential for selection bias and imprecision in the results, thus there is uncertainty around the effect estimates. The trial did not report recurrence, time to healing, adverse events, or adherence to compression therapy (Table 1).

Low quality evidence from another trial indicates that a community‐based nurse counselling and behaviour modification and exercise program (Lively Legs) did not improve healing rates, recurrence and adherence to compression any more than attendance at an outpatient wound clinic. The evidence was downgraded to low quality due to potential for selection bias and imprecision in the results so there is uncertainty around the effect estimates. This trial did not report time to healing, adverse events, quality of life, or pain (Table 2).

One trial of video‐delivered education versus written education in a pamphlet of venous leg ulcer management did not report any of the outcomes of interest to this review (Table 3) The trial reported only patient knowledge of venous leg ulcer disease and management.

We found no studies that assessed other interventions that aim to improve adherence to compression therapy, such as healthcare system or educational interventions.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

There was scant evidence available to enable us to assess the benefits of specific educational interventions. i.e. video compared with written information and no evidence to support or refute the benefits of educational interventions generally, as no outcomes included in this review were reported. There was limited evidence available to enable us to assess the benefits of community‐based nursing models of care (Leg Club and Lively Legs) and no evidence to support or refute other interventions that aim to improve adherence to compression therapy such as healthcare and educational programs.

We identified only one trial of educational interventions that evaluated and compared two educational tools (video and written pamphlet) to improve patient knowledge of venous disease and ulcer management of patients with previous or current active venous leg ulcers (Baquerizo Nole 2015). The small trial of educational interventions was based in Miami USA but results cannot be generalised due to small sample size, and lack of clear reporting as per CONSORT guidelines(CONSORT 2010). The implied aim of this study was to evaluate and compare educational interventions (video and written pamphlet) to improve patient knowledge. We were unable to substantiate a difference in improved knowledge with video or written pamphlet.

We identified two small trials of community‐based nurse‐led interventions that aimed to help people adhere to compression therapy. One trial of peer‐support (Leg Club), based in Australia, was based on a UK program that may be transferable to other healthcare systems internationally. However, Edwards 2009 paid research staff to administer interventions, and volunteer drivers to collect and transport participants to and from the venue, which raises some questions about generalisability to usual practice settings. The stated aim of this program was primarily to improve quality of life and psychological well being (Lindsay 2001). We could not demonstrate a difference in quality of life between groups in our analysis and an improvement in adherence (and therefore an improvement in healing rates and reduced recurrence) is not supported by the available evidence.

The Lively Legs programme was developed in the Netherlands and is a community‐based 'coaching' intervention to support adherence to compression. This programme was also nurse‐led, but nurses were trained in psychological techniques to tailor their coaching to assess adherence, motivation, goal‐setting and relapse prevention. The Lively Legs programme also has potential to be used internationally, not withstanding the caveats required for training and cost.

The completeness of the evidence was hampered by failure of trials to report important outcomes. Time to healing and adverse events were not reported in either trial; recurrence and adherence were not reported in the Leg Club trial (Edwards 2009); and quality of life and pain were not reported in the Lively Legs trial (Heinen 2012) or the trial of education interventions (Baquerizo Nole 2015).

Quality of the evidence

Only low quality evidence was available from two trials that assessed the use of community‐based interventions (67 participants and 184 participants). The evidence was downgraded because of the potential for selection bias and the low number of participants, which leads to uncertainties around the effect estimates, and their precision. (Table 1; Table 2). Further studies are likely to change these results, but we do not know in which direction.

There was no evidence available for any of the primary or secondary outcomes of this review from one small trial that evaluated educational interventions (20 participants) (Table 3).

We suspect that the small number of trials identified is likely to be indicative of a lack of research in the area, rather than to publication bias.

Potential biases in the review process

We are confident that the broad literature search used in this review has captured most of the relevant literature, and minimised the likelihood that we have missed any relevant trials. Two review authors independently selected trials, extracted data, and assessed risk of bias, in order to minimise bias.

Despite extensive searching, it is possible that we missed some trials that met our criteria. The literature on patient adherence to compression is not well indexed because the number of studies is quite small, while, in trials, adherence to compression is not often reported and it is unclear whether it is measured. We invite readers to notify us of any studies, published or unpublished, that meet our criteria.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This is the first review of randomised studies that address this question, as far as we are aware. Earlier non‐randomised studies indicated that an educational intervention (Brooks 2004) and a community‐based nursing clinic emphasising socialisation and peer‐support (Leg Club) (Lindsay 2001) may increase adherence to compression, but do not report whether this leads to increased healing rates and decreased recurrence.

Reviews clearly show that compression therapy is the mainstay treatment for healing venous ulcers (Cullum 2001; Nelson 2012; O'Meara 2012). The benefits from such treatments diminish according to the degree of non‐adherence to the treatment (Sackett 1996; Van Hecke 2008). Despite the development of new compression bandage device systems and substantial evidence from RCTs in the past two decades (O'Meara 2012), there is a lack of evidence investigating non‐adherence and effectiveness of strategies to help patients increase adherence.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The conclusions we can draw in our systematic review are limited by the quality and number of trials that met our inclusion criteria, and a lack of reporting of important outcomes. The trials we identified were susceptible to bias, and hampered by inadequate reporting and small sample sizes, which may have hidden real benefits. There is a lack of studies that report on interventions that improve adherence to compression therapy. This absence of reliable evidence means that, at present, it is not possible either to recommend or discourage educational interventions (video compared with written information) or nurse‐led clinic care interventions over standard care (home care or outpatient clinic) in terms of increasing adherence to compression bandaging.

Implications for research.

Further high quality research is required before definitive conclusions can be made about the benefits of educational interventions and community‐based clinics incorporating multi‐faceted interventions designed to promote adherence to compression therapy, and ultimately improved healing in people with venous leg ulcers.

To achieve benefits from current compression therapies we need further innovation in treatment methods and a better understanding of strategies to improve adherence to intervention. This needs to be tested within clinical trials. Future trials should clearly report baseline participant characteristics (i.e. wound size and duration) and include participants who do not adhere to compression at baseline to reflect the variability in adherence in this population. Trialists could consider including a lower level of compression bandaging as one intervention in order to assess whether this improves adherence and, potentially, healing (Weller 2012). Trials should report relevant outcomes, such as healing and recurrence, as well as possible reasons for non‐adherence from the participant's perspective. Future trials should conform to (CONSORT 2010) recommendations and be designed with sufficient power to detect a true treatment effect.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 July 2015 | New search has been performed | First update. New search. One new study that met inclusion criteria and one ongoing study were identified. |

| 15 July 2015 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | One new study included in the update. |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank peer referees Liz McInnes, Mieke Flour, Anne‐Marie Bagnall, Una Adderley, Gill Worthy, Janet Yarrow, Sala Seppanen. We would also like to thank copy editor Elizabeth Royle.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

The Cochrane Wounds Specialised Register

#1 ((ulcer* NEAR3 (leg* or venous or varicose or stasis or crural)) or "ulcus cruris") #2 (compliance or adherence or concordance or "patient education" or community or multidisciplinary or "social support" or self‐help or "self help" or "leg club") #3 #1 AND #2

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Patient Compliance] explode all trees #2 (compliance or adherence or concordance):ti,ab,kw #3 MeSH descriptor: [Patient Education as Topic] explode all trees #4 "patient education":ti,ab,kw #5 MeSH descriptor: [Community Health Nursing] explode all trees #6 community next health next nurs*:ti,ab,kw #7 community next nurs*:ti,ab,kw #8 MeSH descriptor: [Community Health Centers] explode all trees #9 (community next clinic*) or (community next health next cent*) or (primary next care next clinic*):ti,ab,kw #10 (multidisciplinary near/3 wound*):ti,ab,kw #11 MeSH descriptor: [Nurse Practitioners] explode all trees #12 (practice next nurse*) or (nurse next practitioner*):ti,ab,kw #13 MeSH descriptor: [Social Support] explode all trees #14 "social support":ti,ab,kw #15 MeSH descriptor: [Self‐Help Groups] explode all trees #16 (self next help next group*) or (support next group*) or (leg next club*):ti,ab,kw #17 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 #18 MeSH descriptor: [Leg Ulcer] explode all trees #19 (varicose next ulcer*) or (venous next ulcer*) or (leg next ulcer*) or (foot next ulcer*) or (stasis next ulcer*) or ((lower next extremit*) near/2 ulcer*) or (crural next ulcer*) or "ulcus cruris":ti,ab,kw #20 #18 or #19 #21 #17 and #20

Ovid MEDLINE

1 exp Patient Compliance/ 2 (compliance or adherence or concordance).tw. 3 exp Patient Education as Topic/ 4 patient education.tw. 5 exp Community Health Nursing/ 6 (community health nurs* or community nurs*).tw. 7 exp Community Health Centers/ 8 (community clinic* or community health cent* or primary care clinic*).tw. 9 (multidisciplinary adj3 wound*).tw. 10 exp Nurse Practitioners/ 11 (practice nurse* or nurse practitioner*).tw. 12 exp Social Support/ 13 social support.tw. 14 exp Self‐Help Groups/ 15 (self help group* or support group* or leg club*).tw. 16 or/1‐15 17 exp Leg Ulcer/ 18 (varicose ulcer* or venous ulcer* or leg ulcer* or foot ulcer* or (feet adj ulcer*) or stasis ulcer* or (lower extremit* adj ulcer*) or crural ulcer* or ulcus cruris).tw. 19 or/17‐18 20 16 and 19 21 randomized controlled trial.pt. 22 controlled clinical trial.pt. 23 randomized.ab. 24 placebo.ab. 25 clinical trials as topic.sh. 26 randomly.ab. 27 trial.ti. 28 or/21‐27 29 (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. 30 28 not 29 31 20 and 30

Ovid EMBASE

1 exp patient compliance/ 2 (compliance or adherence or concordance).tw. 3 exp patient education/ 4 patient education.tw. 5 exp community health nursing/ 6 (community health nurs* or community nurs*).tw. 7 (community clinic* or community health cent* or primary care clinic*).tw. 8 (multidisciplinary adj3 wound*).tw. 9 exp nurse practitioner/ 10 (practice nurse* or nurse practitioner*).tw. 11 exp social support/ 12 social support.tw. 13 exp self help/ 14 exp support group/ 15 (self help group* or support group* or leg club*).tw. 16 or/1‐15 17 exp leg ulcer/ 18 (varicose ulcer* or venous ulcer* or leg ulcer* or foot ulcer* or (feet adj ulcer*) or stasis ulcer* or (lower extremit* adj ulcer*) or crural ulcer* or ulcus cruris).tw. 19 or/17‐18 20 16 and 19 21 Clinical trial/ 22 Randomized controlled trials/ 23 Random Allocation/ 24 Single‐Blind Method/ 25 Double‐Blind Method/ 26 Cross‐Over Studies/ 27 Placebos/ 28 Randomi?ed controlled trial$.tw. 29 RCT.tw. 30 Random allocation.tw. 31 Randomly allocated.tw. 32 Allocated randomly.tw. 33 (allocated adj2 random).tw. 34 Single blind$.tw. 35 Double blind$.tw. 36 ((treble or triple) adj blind$).tw. 37 Placebo$.tw. 38 Prospective Studies/ 39 or/21‐38 40 Case study/ 41 Case report.tw. 42 Abstract report/ or letter/ 43 or/40‐42 44 39 not 43 45 animal/ 46 human/ 47 45 not 46 48 44 not 47 49 20 and 48

EBSCO CINAHL

S36 S22 AND S35 S35 S23 OR S24 OR S25 OR S26 OR S27 OR S28 OR S29 OR S30 OR S31 OR S32 OR S33 OR S34 S34 TI allocat* random* or AB allocat* random* S33 MH "Quantitative Studies" S32 TI placebo* or AB placebo* S31 MH "Placebos" S30 TI random* allocat* or AB random* allocat* S29 MH "Random Assignment" S28 TI randomi?ed control* trial* or AB randomi?ed control* trial* S27 AB ( singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl* ) and AB ( blind* or mask* ) S26 TI ( singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl* ) and TI ( blind* or mask* ) S25 TI clinic* N1 trial* or AB clinic* N1 trial* S24 PT Clinical trial S23 MH "Clinical Trials+" S22 S17 and S21 S21 S18 or S19 or S20 S20 TI lower extremity N3 ulcer* or AB lower extremity N3 ulcer* S19 TI (varicose ulcer* or venous ulcer* or leg ulcer* or foot ulcer* or (feet N1 ulcer*) or stasis ulcer* or crural ulcer*) or AB (varicose ulcer* or venous ulcer* or leg ulcer* or foot ulcer* or (feet N1 ulcer*) or stasis ulcer* or crural ulcer*) S18 (MH "Leg Ulcer+") S17 S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 S16 TI (self help group* or support group* or leg club* ) or AB ( self help group* or support group* or leg club* ) S15 TI social support or AB social support S14 (MH "Support Groups+") S13 (MH "Support, Psychosocial") S12 TI ( practice nurse* or nurse practitioner* ) or AB ( practice nurse* or nurse practitioner* ) S11 (MH "Nurse Practitioners+") S10 TI multidisciplinary N3 wound* or AB multidisciplinary N3 wound* S9 TI (community clinic* or community health cent* or primary care clinic*) or AB (community clinic* or community health cent* or primary care clinic*) S8 (MH "Community Health Centers") S7 TI community nurs* or AB community nurs* S6 TI community health nurs* or AB community health nurs* S5 (MH "Community Health Nursing+") S4 TI patient education or AB patient education S3 (MH "Patient Education+") S2 TI ( compliance or adherence or concordance ) or AB ( compliance or adherence or concordance ) S1 (MH "Patient Compliance+")

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Leg Club versus nurse home visits.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of people healed | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 3 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 6 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Quality of life (Spitzer's quality of life index, 0‐10) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Pain at 6 months (0 to 100 scale) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Comparison 2. Lively Legs programme versus outpatient wound clinic.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of people healed | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Proportion with recurrence | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Proportion fully adherent to compression | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 6 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 12 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.3 18 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Baquerizo Nole 2015.

| Methods | Parallel RCT to evaluate the effectiveness of an educational intervention to improve knowledge of venous disease and ulcer management. Setting: Wound healing research clinic in Miami, USA. |

|

| Participants | 20 patients who attended wound healing research clinic (10 video; 10 pamphlet) Inclusion criteria: not reported Exclusion criteria: not reported |

|

| Interventions | Both groups instructed to complete baseline test of 15 questions about venous leg ulcer pathophysiology, management and lifestyle, compression therapy and reasons to seek care between visits Education intervention with video; or Education received in written format (pamphlet). Co‐interventions: not reported. |

|

| Outcomes | Outcome measured at baseline, immediately after the intervention and at 4 weeks: Outcomes included in this review:

Outcome included in trial

Outcomes not reported in trial

|

|

| Source of funding | No funding declaration | |

| Notes | Letter to the editor; wrote to author requesting additional outcome data. Author response: No further outcomes were measured. Not registered in clinical trials registry. No outcomes were reported that could be included in this review. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported Quote...' twenty patients were enrolled, half were randomised to receive the video... half to receive the pamphlet'. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not reported,but participants were probably aware of their intervention allocation |