Abstract

There are many online resources that focus on chemical diversity of natural compounds, but only handful of resources exist that focus solely on flavonoid compounds and integrate structural and functional properties; however, extensive collated flavonoid literature is still unavailable to scientific community. Here we present an open access database ‘FlavoDb’ that is focused on providing physicochemical properties as well as topological descriptors that can be effectively implemented in deducing large scale quantitative structure property models of flavonoid compounds. In the current version of database, we present data on 1, 19,400 flavonoid compounds, thereby covering most of the known structural space of flavonoid class of compounds. Moreover, effective structure searching tool presented here is expected to provide an interactive and easy-to-use tool for obtaining flavonoid-based literature and allied information. Data from FlavoDb can be freely accessed via its intuitive graphical user interface made available at following web address: http://bioinfo.net.in/flavodb/home.html.

Keywords: Phytochemicals, Flavone, Flavanones, Isoflavones, Neoflavonoids, Topological descriptor, Drug discovery, QSPR, Database

Introduction

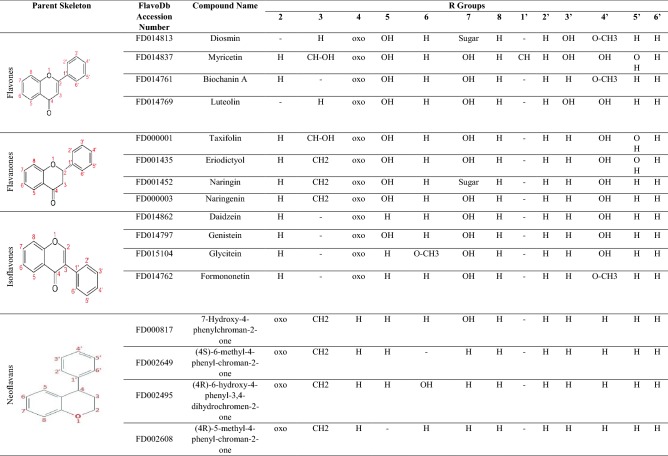

Flavonoids correspond to a very diverse set of polyphenolic set of compounds from plant origin. This class of compound is attributed with enormous structural as well as functional heterogeneity. Besides their classical anti-oxidant effect, these compounds are known to possess antibacterial, anti-parasitic, anti-cancer, cardio protective, immune system promoting, anti-inflammatory and skin protective activity from ultra violet radiation; all these properties are effectively reviewed by Tungmunnithum et al. (2018). Additionally, flavonoids are also established as effective agents in management of autoimmune conditions like multiple sclerosis (Coe et al. 2018), rheumatoid arthritis (Chu et al. 2018) and many other conditions like neurodegeneration, psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematosus and inflammatory bowel disease [these biological effects are reviewed by Rengasamy et al. (2018)]. Flavonoids possess a characteristic tri-ringed flavone as primary chemical backbone formed of fused heterocyclic chromen group (Ring C and A). This chromen group is further connected to phenyl group that corresponds to Ring B (Gacche et al. 2015a, b). Based on arrangement of oxo group, B-ring and bond order between carbon atom C2 and C3 in C ring, flavonoids are further subcategorized as Isoflavones, Flavanones, Neoflavonoids and Flavones. Moreover, based on frame-up of hydroxyl substituents, more subclasses like Flavanols and Flavonols are frequently specified (Table 1).

Table 1.

Table showing some of the representative members of four major classes of flavonoids used in this study along with their Accession numbers in FlavoDb, common name and substituents R groups

It is believed that the substituents on the parent flavonoid scaffold govern the biological activities of these compounds (Martinez-Gonzalez et al. 2019). Enormous structural diversity, in fact, limits derivation of exact structure property relation (SPR) model for this class of compounds and thus warrants an urgent need to localize structural and functional information of these compounds (Cui et al. 2018). One of the biggest bottlenecks that scientific community faces today in developing effective quantitative structure property relationship (QSPR) models for flavonoids is the unavailability of a collated structural and functional details of flavonoids. Moreover, new and more effective descriptors are required for generation of such quantitative models. Therefore, in continuation of our interest in flavonoid research (Gacche et al. 2011; Patil et al. 2016; Patil and Gacche 2017) we initiated developing of a database, FlavoDb, to integrate data on flavonoid compounds.

Prior attempt to develop such database suffers in terms of data comprehensiveness since information on very limited flavonoid compounds was presented (Kinoshita et al. 2006). Most importantly, there is no active web interface to this database thereby limiting the data accessibility to general scientific community (Kinoshita et al. 2006). In contrast, the current version of FlavoDb hosts data on 1, 19,400 natural as well as synthetic flavonoid compounds, thereby covering majority of known flavonoid structural space. One of the objectives of developing a separate resource devoted to flavonoids is to bridge the gap of availability of novel descriptors and the published data on flavonoids. FlavoDb is aimed to provide comprehensive information on various flavonoid properties that is expected to not only enable effective deduction of QSPR models but also act as a central repository of flavonoid literature.

Materials and methods

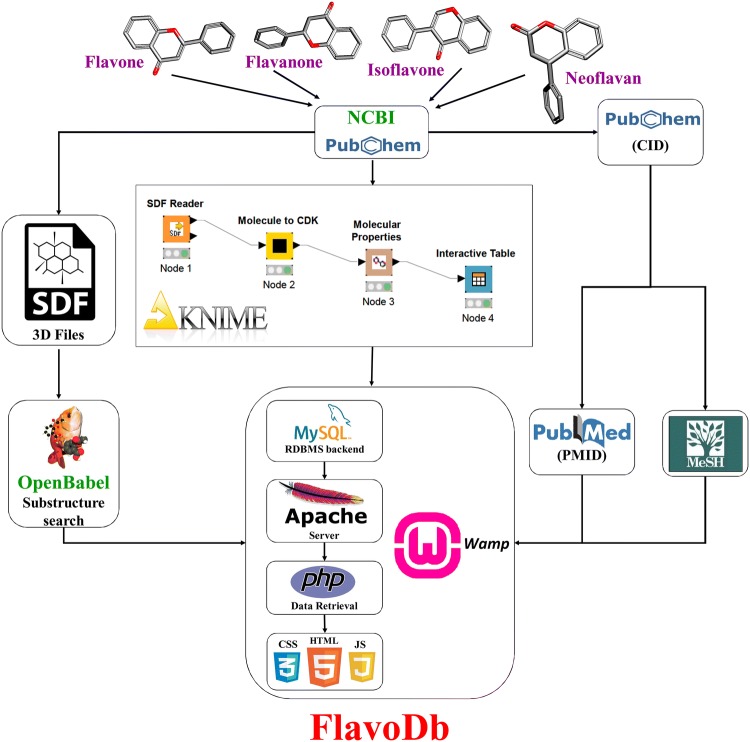

Data retrieval and processing

Four basic flavonoid scaffolds were used for data extraction from PubChem compound resource. A substructure query was performed at PubChem Compound database by drawing the skeletons of parent flavone, flavanone, isoflavone and neoflavan scaffolds. Since flavanols stand as a subclass of flavone, inclusion of flavone in substructure search ensured presence of all flavonols in the present database. The resulting compound’s structures were downloaded in four separate SDF files. In order to ensure removal of duplicate records, all four SDF files were merged together and unique command from OpenBabel (O’Boyle et al. 2011) was used. Simultaneously, the images of corresponding flavonoids were also downloaded from PubChem. PubChem provides the literature associated with its compound to be downloaded from its FTP site (ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubchem/Compound/Extras/CID-PMID.gz. Accessed 16 April 2018) as a single archive file. This archive file (CID-PMID file) represents the literature information by listing all PMIDs (PubMed IDs from PubMed) in the corresponding Compound IDs (CIDs from PubChem). The content of the original CID-PMID file corresponds to references of all compounds in PubChem compound resource. A script was then written to extract all PMIDs corresponding to flavonoids of interest and populate them in a separate table in the database. Similarly, common names and synonyms of flavonoids are also associated with CIDs that were downloaded from FTP site (ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubchem/Compound/Extras/CID-MeSH. Accessed 9 October 2018). Common names and synonyms were incorporated in the database as a separate table after processing the list in a similar way done for PMIDs above.

Descriptor and properties calculation

KNIME Version 3.3.1 was used for calculation of physicochemical properties and descriptors of the flavonoid compounds. A KNIME workflow was setup with four nodes, ‘SDF reader’, ‘Molecule to CDK’, ‘Molecular Properties’ and ‘Interactive table’. SDF reader is a generic node provided in a standard chemistry node repository in KNIME that is usually implemented to take SDF file as input and process them appropriately to be used in subsequent nodes. Further calculations were performed using nodes from Chemistry Development Kit (CDK) library. ‘Molecule to CDK’ node is generally used to parse and display the structures and works by converting the elements from the input table’s columns (SDF reader) to its own internal format called CDKCell. Data from CDKCell are further used for calculating physicochemical properties and descriptors. ‘Molecular property’ is a node from CDK toolkit that calculates general properties like LogP, molecular weight (g/mol), H-bond donor, H-bond acceptor, topological polar surface area (Å2), rotatable bond count, heavy atom count, aromatic atoms count, aromatic bond count, bond count, element count that are routinely used in determining QSPRs. Additionally, this node provides some special descriptors like ‘fragment complexity’ that is a standard measure of molecular complexity. Atomic polarizabilities and bond polarizabilities reflect the tendency of distortion of molecular or atomic charge distribution under the influence of externally applied oscillating electromagnetic fields (Zalden et al. 2018), largest chain and largest PI (π) chain descriptors corresponding to the maximum number of atoms in the largest chain and number of atoms in the largest π system, respectively. Sp3 character (fraction of Sp3 carbons) corresponds to the ratio of number of Sp3 hybridized atoms to total number of atoms in a molecule including hydrogens (Yan and Gasteiger 2003). Value of VABC volume descriptor is a group contribution value based on van der Waals volume (Yin et al. 2014). This descriptor is calculated by “sum of atomic and bond contributions (VABC) method” effectively described by Zhao et al. (2003).

Besides these physicochemical descriptors, the database also features some topological descriptors. Topological descriptors are based on graph theory. As per the graph theory, molecules are represented as collection of vertices (atoms) that are connected by edges (bonds between atoms). The two descriptors, i.e., eccentric connectivity index and petitjean number are based on the concept of eccentricity. As per definition by Rao (1994), “eccentricity E(i) of a vertex (i) in a graph G is the distance from i to the vertex farthest from i in G” as shown below (Rao 1994; Sharma et al. 1997).

Eccentric connectivity index is a topological descriptor that is calculated on the basis of valency and eccentricity of every vertex included in a molecular graph. As per its basic definition eccentric connectivity index (ξ) is the sum of product of degree of each (value of i starting from 1 to n) vertex (V) and eccentricity (I) in a hydrogen deficient molecular graph (Sharma et al. 1997) as shown below.

Petitjean number is another topological descriptor most often related to the eccentric connectivity index that accounts for the distance of a vertex in a graph to the most remote vertex in a graph (Petitjean 1992). Dearden defined the Zagreb index as “the sum of the squares of the number of non-hydrogen bonds formed by each heavy atom” (Gutman and Trinajstic 1972; Dearden 2017). Values from topological descriptor like vertex adjacency magnitude enables the user to distinguish molecules on the basis of branching degree, size and flexibility (Thangapandian et al. 2011). These descriptors serve to be very handy while comparing properties of very similar molecules since this descriptor considers the molecules in terms of subset structure (Shi et al. 1998).

Database implementation

FlavoDb was configured in typical WAMP (Windows +APACHE +MySQL +PHP) environment that runs on Windows based machine. The database was developed on conventional three layer design that consists of presentation layer, middle or intermediate layer and data layer (Jadhav et al. 2013). MySQL backend Relational Database Management System (RDBMS) was used to hold primary data. APACHE was used as main server engine that connects RDBMS to client layer (presentation layer). The presentation layer was developed using HTML, CSS and JavaScript. Middle layer was implemented using PHP.

Structure searching tool

Structure searching tool was implemented as per established protocol published elsewhere (Kolte et al. 2018). Briefly, the structure searching utility was developed on FlavoDb by implementing JAVA based JSME plugin (Bienfait and Ertl 2013). JSME molecular editor enables the user to interactively draw the desired chemical structure or upload the structure in MOL, SDF and SMILES format. All the unique compounds were compiled in a single SDF file. For structure similarity searches, FlavoDb relies on execution of Babel program from the OpenBabel Suite. Upon successful execution of a structure search query on the server, a fingerprint of the query compound in binary form is generated, which is consecutively matched with already precompiled fingerprint data in an SDF file. Before the data are tabulated and displayed on the HTML page, the output is temporarily saved in an intermediate file. A pictorial representation of the methodology is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Summary of development protocol used for FlavoDb

Results and discussion

The initial substructure query made on the PubChem compound database for collecting data was based on four parent flavonoid scaffolds that yielded 1, 29,778 compounds. From these compounds, 10,378 entries were found to be duplicated and hence removed. Thus the resource contains 1, 19,400 unique flavonoid compounds. Similarly, the original CID-PMID file contained 50,510,380 (fifty million, five hundred ten thousand, three hundred eighty) records. After processing the file to extract only references for flavonoids, total of 1, 33,031 (one hundred thirty-three thousand and thirty one) citations were found to be associated with various flavonoid entries in current version of FlavoDb. The utilization and important features of the database can be best understood using following three model examples.

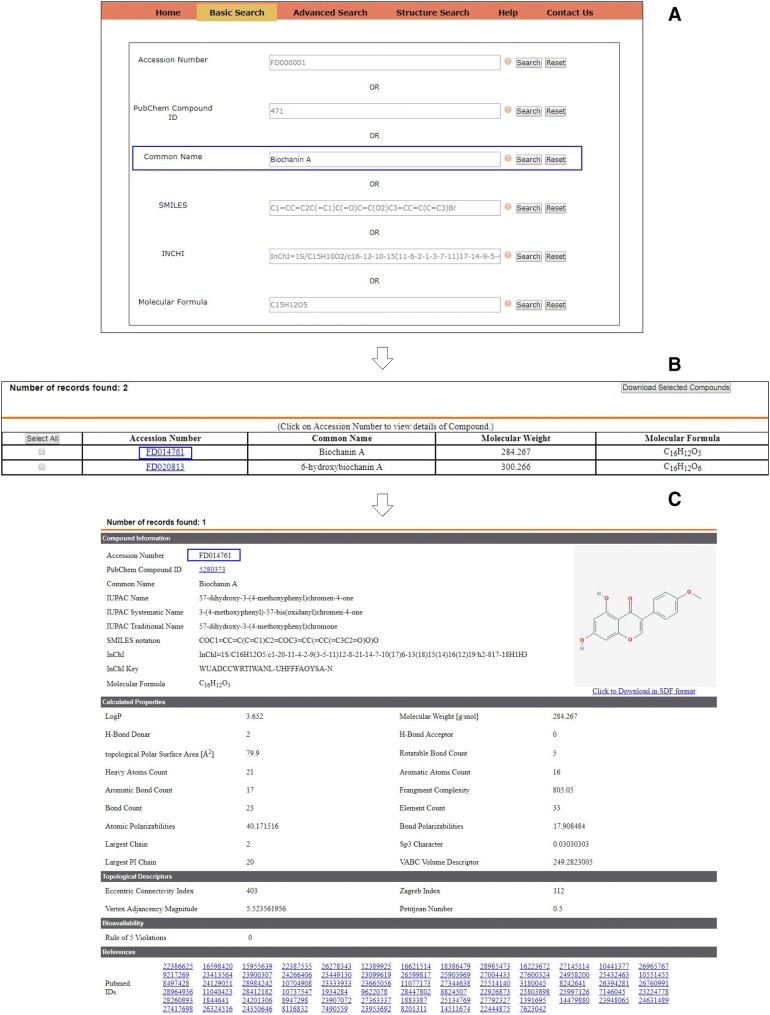

Model query for basic search

The basic search is developed on this database in order to enable user to obtain information on a specific flavonoid compound. Thus, basic search can be conducted using flavonoid’s common name, SMILES (simplified molecular-input line-entry system) notations, PubChem compound ID, molecular formula and InChI (international chemical identifier) code. Upon successful execution of the query, the resulting page tabulates the results in five major sections like ‘Compound information’, ‘Calculated properties’, ‘Topological descriptors’, ‘Bioavailability’ and ‘References’. The section ‘Compound information’ deals with description of compound’s basic information like its common name, IUPAC names, link to PubChem compound database, SMILES, molecular formula, InChI and InChI Key. InChI Key being unique and short in comparison to IUPAC names or InChI code, its inclusion in database offers an added advantage (Heller et al. 2013; Loharch et al. 2015). Section ‘Calculated properties’ lists all physicochemical properties calculated via KNIME workflow. This section offers data for basic descriptors like LogP, molecular weight, hydrogen bond donors, hydrogen bond acceptors, topological polar surface area, rotatable bonds, heavy atom count, aromatic atom count, aromatic bond count, bond count and element count. In addition, we also computed and display some interesting properties like fragment complexity descriptor, largest chain and largest π chain, Sp3 character, VABC volume descriptor along with atomic and bond polarizabilities that are rarely discussed in literature in terms of flavonoid compounds. The implication of these properties in general drug discovery are discussed as follows.

Fragment complexity descriptor is recognized as an important criteria in drug discovery since it is established that complexity in ligand molecule adversely affects the molecular recognition by the target protein (Hann et al. 2001). Hence less complex molecules are preferred as starting point in drug development procedures. The experimental application of π chain descriptor has been recently published in terms of pupaecidal and larvicidal activity against Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito (Andrade-Ochoa et al. 2018). In this study, the compounds with lower number of π chains have been found to be associated with lower pupaecidal and larvicidal activity of terpenoids and terpenes class of compounds. The Sp3 character is frequently associated with determining various properties of compounds including solubility of compounds (Kenny and Montanari 2013), CYP450 inhibition, reducing protein binding effect, hERG binding potential and modulation of Caco-2 permeability (Yang et al. 2012). Similarly, the effect of volume on activity of compounds has been recently explored in term of VABC calculation (Halberstadt et al. 2018). In this study, the psychedelic effects of various lysergamide lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) analogues via interaction with 5-HT2A receptor have been determined to correlate with volume properties of the inhibitor. Properties of compounds like atomic and bond polarizabilities are well established to link with the nerve toxicity in animal as well as human experimental models (Hansch and Kurup 2003).

In addition, we also provide an account of topological descriptors of flavonoids like eccentric connectivity index, Petitjean number, vertex adjacency magnitude and Zagreb index which are gaining an increased importance in defining QSPR models (Dearden 2017). For example, eccentricity-derived properties (including eccentric connectivity index and Petitjean number) have been found to affect the analgesic properties of more than 90 methylene methyl ester and piperidinyl methyl ester derivatives (Sharma et al. 1997). Values of Zagreb index have been demonstrated in determining effective anti-inflammatory properties of N-arylanthranilic acid analogues (Bajaj et al. 2005) and binding/clearance potential of antibiotics like cephalosporin in humans (Dureja et al. 2008). Values of vertex adjacency magnitude of quinolone-based compounds is reported to affect the NS2B/NS3 protease inhibitory action in Dengue Type-2 (DENV2) virus (Hariono et al. 2014). Inclusion of such diverse set of descriptors has added an extra scientific dimension to the data made available in this resource.

Section for bioavailability indicates the number of violations from Lipinski’s Rule of five (Lipinski et al. 2001). The final section provides the complete list of references associated with the flavonoid compound which are linked with PubMed. User can download the structure of individual compound in SDF format using ‘Click to download in SDF format’ link. Figure 2 demonstrates the result obtained from basic query taking Biochanin A as an example.

Fig. 2.

Steps involved while performing basic search on the database. Various options available to perform basic query (a). Intermediate page tabulating multiple hits (b) and detailed entry with all flavonoid properties, linked literature and 2D depiction of the compound (c)

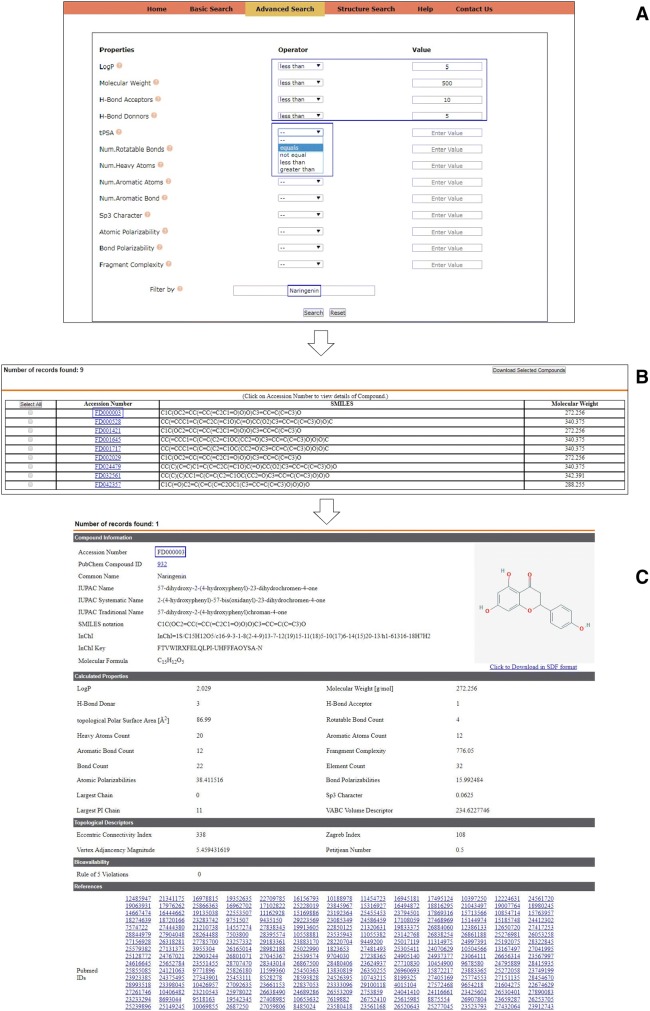

Model query for advanced search

Advanced search system empower user to formulate and execute complex queries. User can define any complex query combining various properties with an array of logical operators like =, ≠, < and >. User has independence to formulate the query individually or club them in combination with other properties or operators. Such a feature enables the user to perform queries on user-defined filtering rules or search the database using already defined rules including but not limited to Rule of 5 (Lipinski et al. 2001), Rule of 3 (Congreve et al. 2003), Opera drug-like (Oprea 2000), Opera lead-like (Oprea et al. 2001), Veber (Veber et al. 2002), Egan (Egan et al. 2000), Martin (Martin 2005), etc. Additionally, it is also possible to search for a specific class of compound using multiple properties; for example, all Naringenin-like compounds following Rule of 5 can be effectively retrieved as demonstrated in Fig. 3. Since multiple hits are expected in such queries, an intermediate page is designed to appear tabulating accession numbers, SMILES and molecular weights of the identified hits. A batch download function is also made available on the intermediate page in the form of ‘Download selected’ button that allows the user to effectively retrieve all or set of selected compounds in a single SDF file and save them on the local disk. The detailed entry for the selected flavonoid compound can be reached by clicking the accession numbers on the intermediate page.

Fig. 3.

Steps involved while performing advanced search on the database. Complete list of properties available for searching the database and implementation of various operators is highlighted in blue box (a). Intermediate page tabulating multiple hits (b) and detailed entry of flavonoid Naringenin (c)

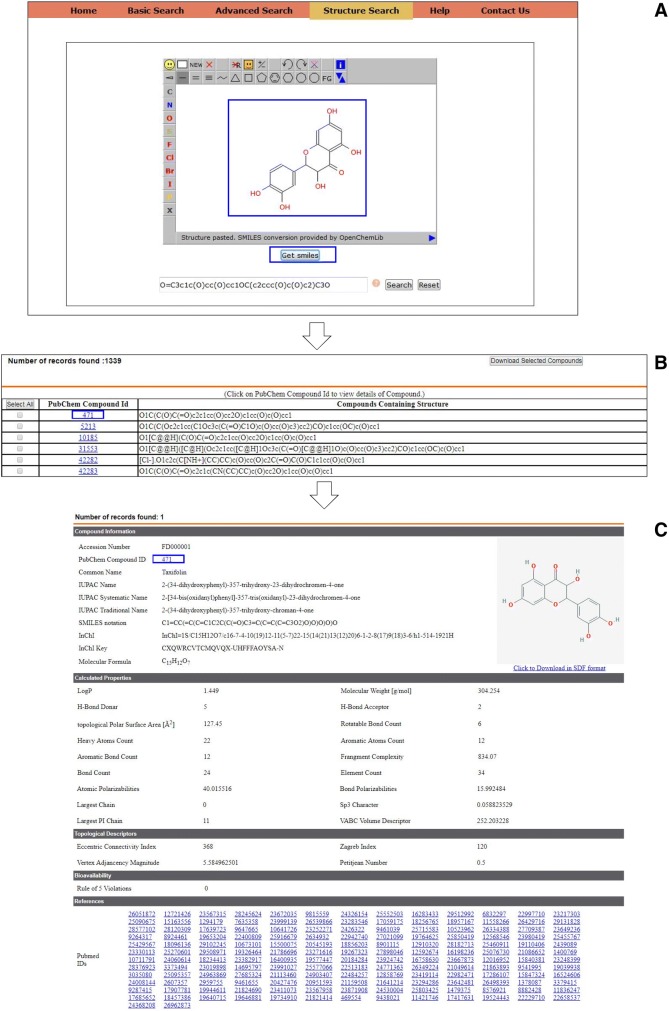

Model query for structure search

This function is intended to allow the user to search compounds similar to given input compound. For example, as demonstrated in Fig. 4, the user can search for compounds that are structurally similar to Taxifolin by interactively drawing the structure in JSME molecular editor (Bienfait and Ertl 2013). Upon successful execution of the query, an intermediate page shall appear tabulating the SMILES and PubChem identifiers of the structurally similar compounds. All the features discussed for intermediate page in advanced search utility above are applicable here.

Fig. 4.

Steps involved while performing structure search on the database. Interface for JSME editor with interactively drawn structure of Taxifolin (a). An intermediate page populated with flavonoids structurally similar to Taxifolin (b). Detailed Entry of Taxifolin (c)

Role of flavonoids in management of a few major diseases

Recent literature suggests interesting correlation of various classes of flavonoids with some major human diseases and medical conditions. The following section is aimed to summarize the role of flavonoids in therapeutic perspective.

Various flavonols like Rutin, Fisetin, Kaempferol, Isorhamnetin and Morin are established to possess anti-diabetic effects. For example, all the above mentioned flavonols induce the antidiabetic effect using antihyperglycemic or anti hypolipemic activities (AL-Ishaq RK etal. 2019). Various flavanones like Hesperidin are reported to act by modulating enzymatic functions of glucose metabolism enzymes to reduce glucose levels in blood (Jung et al. 2004, Agrawal et al. 2014). Naringenin is demonstrated to act as antidiabetic agent by delaying glucose absorption by inhibiting enzymes like α-glucosidases expressed in intestines (Li et al. 2006). It is also associated with activation of AMPK signalling pathway that results in maintaining insulin sensitivity and improves tolerance to glucose levels (Pu et al. 2012). Flavones like Baicalein are reported to act by modulating the MPK pathway; it phosphorylates IRS-1/Akt and simultaneously dephosphorylate NFK-B protein. These events in turn result in reduction of insulin resistance effect (Yin et al. 2018). Apigenin enhances the translocation of GLUT4 transport on surface and helps in lowering the glucose level in blood (Kim et al. 2007). It is also known to increase cholesterol in serum and enhance lipid peroxidation to show its anti-diabetic effects (Panda and Kar 2007). Isoflavones like Genistein and Daidzein are also characterized to play an important role in controlling diabetic conditions. Genistein is demonstrated to activate the PKA/cAMP pathway by inhibition of tyrosine kinase activity of receptors resulting in reduction of hyperglycemia (Palanisamy et al. 2008; Valsecchi et al. 2011). In a Golden Syrian hamsters involving animal study, another Isoflavone Daidzein is suspected to decrease blood glucose levels by interfering the signalling pathway with AMPK dependent phosphorylation event (Das et al. 2018).

Flavones like Lutein activates apoptosis event by down regulating genes like Bax, Bcl-2, Bad (Ma et al. 2015) and up regulates p38 and caspase cascade to act as anti-cancer agents (Cho et al. 2015). Another flavone, Apigenin, upregulates Snail/Slug and Akt pathway that restricts the migratory and invasive properties of cancerous cells (Chang et al. 2018). Flavonols like Kaempferol are experimentally validated to down regulate STAT3 or claudin-2 dependent signalling to inhibit inhibition of cell proliferation (Sonoki et al. 2017), while Fisetin activates Apoptosis by modulating ERK mediated signalling (Wang and Huang 2018). Flavanones including Hesperetin interfere with HFKb-p65 signalling resulting in reduction of cancer cell proliferation (Ramteke and Yadav 2019), while Naringenin is known to induce apoptosis by upregulating DR5 and Bid pathways (Jin et al. 2011). Isoflavones like Daidzein result in apoptosis in cancerous cells by down regulating STK and YAP1 signalling (Chen et al. 2017), while Genistein brings out the same effect by up regulating Cdc25B and survivin dependent signalling (Tian et al. 2014).

Flavones (Formononetin, Biochanin-A, Diosmin and Myricetin), Flavanones (Taxifolin, Naringin, Naringenin, Hesperidin and Hesperitin) and Flavonol like Silibinin are experimentally demonstrated to be effective Cyclooxygenase inhibitors and thereby generate an excellent COX-2 selective anti-inflammatory response (Meshram et al. 2019; Gacche et al. 2015a, b).

Limitations of the resource

The resource presented here offers molecular descriptor data that can be very effectively utilized to generate and analyse QSPR models. However, in its current version, activity-related data are not presented in the database that might limit its utility in generating QSAR models. Further developments are on the way to incorporate activity data to FlavoDb in upcoming versions.

Conclusion

In the current report we presented effective development of a user-friendly chemical resource ‘FlavoDb’ that hosts data on 1, 19,400 flavonoid compounds from natural as well as synthetic origin. FlavoDb hosts data on not only general properties of flavonoids but also features some interesting physicochemical as well as topological properties of nutraceuticals and therapeutic values. The effective querying system designed and described in this report is expected to provide free access to retrieve the relevant flavonoid information for the scientific community. The structural similarity tool implemented here can be used to pinpoint data on flavonoids that are of user’s interest. Finally, we report successful integration of flavonoid’s physicochemical, topological and literature data under a single roof that can aid in derivation of large-scale QSPR models to understand diverse structural and functional aspects of this class of compounds.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Paul Thiessen and Dr. Evan Bolton, staff from NCBI Structure group for their continuous guidance and suggestion to obtain data on literature and MeSH titles from NCBI resource included in this study. We are also thankful to Dr. Sangeeta Sawant, Director, Bioinformatics Centre, SPPU, Pune for providing continuous encouragement and infrastructure for database development. We acknowledge Mr. Bhushan Solanki for critical suggestion during development of this resource. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Compliance with ethical standards:

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Agrawal YO, Sharma PK, Shrivastava B, Ojha S, Upadhya HM, Arya DS, Goyal SN. Hesperidin produces cardioprotective activity via PPAR-γ pathway in ischemic heart disease model in diabetic rats. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11):e111212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AL-Ishaq RK, Abotaleb M, Kubatka P, Kajo K, Büsselberg D. Flavonoids and their anti-diabetic effects: cellular mechanisms and effects to improve blood sugar levels. Biomolecules. 2019;9(9):430. doi: 10.3390/biom9090430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade-Ochoa S, Correa-Basurto J, Rodríguez-Valdez LM, Sánchez-Torres LE, Nogueda-Torres B, Nevárez-Moorillón GV. In vitro and in silico studies of terpenes, terpenoids and related compounds with larvicidal and pupaecidal activity against Culex quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae) Chem Cent J. 2018;12(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s13065-018-0425-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj S, Sambi SS, Madan AK. Prediction of anti-inflammatory activity of Narylanthranilic acids: computational approach using refined Zagreb indices. Croat Chem Acta. 2005;78:165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Bienfait B, Ertl P. JSME: a free molecule editor in JavaScript. J Cheminform. 2013;5:24. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JH, Cheng CW, Yang YC, Chen WS, Hung WY, Chow JM, Chen PS, Hsiao M, Lee WJ, Chien MH. Downregulating CD26/DPPIV by apigenin modulates the interplay between Akt and Snail/Slug signaling to restrain metastasis of lung cancer with multiple EGFR statuses. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37(1):199. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0869-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Miao H, Zhu Z, Zhang H, Huang H. Daidzein induces apoptosis of non-small cell lung cancer cells by restoring STK 4/YAP 1 signaling. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2017;10:15205–15212. [Google Scholar]

- Cho HJ, Ahn KC, Choi JY, Hwang SG, Kim WJ, Um HD, Park JK. Luteolin acts as a radiosensitizer in non-small cell lung cancer cells by enhancing apoptotic cell death through activation of a p38/ROS/caspase cascade. Int J Oncol. 2015;46(3):1149–1158. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu J, Wang X, Bi H, Li L, Ren M, Wang J. Dihydromyricetin relieves rheumatoid arthritis symptoms and suppresses expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines via the activation of Nrf2 pathway in rheumatoid arthritis model. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;59:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe S, Collett J, Izadi H, Wade DT, Clegg M, Harrison JM, Buckingham E, Cavey A, DeLuca GC, Palace J, Dawes H. A protocol for a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled feasibility study to determine whether the daily consumption of flavonoid-rich pure cocoa has the potential to reduce fatigue in people with relapsing and remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2018;4:35. doi: 10.1186/s40814-018-0230-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congreve M, Carr R, Murray C, Jhoti H. A ‘rule of three’ for fragment-based lead discovery? Drug Discov Today. 2003;8(19):876–877. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02831-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Liu X, Chow LMC. Flavonoids as P-gp inhibitors: a systematic review of SARs. Curr Med Chem. 2018 doi: 10.2174/0929867325666181001115225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das D, Sarkar S, Bordoloi J, Wann SB, Kalita J, Manna P. Daidzein, its effects on impaired glucose and lipid metabolism and vascular inflammation associated with type 2 diabetes. BioFactors. 2018;44(5):407–417. doi: 10.1002/biof.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearden JC. Advances in QSAR. In: Roy K, editor. The use of topological indices in QSAR and QSPR modeling. New York: Springer International Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dureja H, Gupta S, Madan AK. Topological models for prediction of pharmacokinetic parameters of cephalosporins using random forest, decision tree and moving average analysis. Sci Pharm. 2008;76:377–394. [Google Scholar]

- Egan WJ, Merz KM, Jr, Baldwin JJ. Prediction of drug absorption using multivariate statistics. J Med Chem. 2000;43(21):3867–3877. doi: 10.1021/jm000292e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gacche RN, Shegokar HD, Gond DS, Yang Z, Jadhav AD. Evaluation of selected flavonoids as antiangiogenic, anticancer, and radical scavenging agents: an experimental and in silico analysis. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2011;61(3):651–663. doi: 10.1007/s12013-011-9251-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gacche RN, Meshram RJ, Shegokar HD, Gond DS, Kamble SS, Dhabadge VN, Utage BG, Patil KK, More RA. Flavonoids as a scaffold for development of novel anti-angiogenic agents: an experimental and computational enquiry. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2015;577–578:35–48. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman I, Trinajstic N. Graph theory and molecular orbitals. Total p-electron energy of alternant hydrocarbons. Chem Phys Lett. 1972;17:535–538. [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt AL, Klein LM, Chatha M, Valenzuela LB, Stratford A, Wallach J, Nichols DE, Brandt SD. Pharmacological characterization of the LSD analog N-ethyl-N-cyclopropyl lysergamide (ECPLA) Psychopharmacology. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s00213-018-5055-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann MM, Leach AR, Harper G. Molecular complexity and its impact on the probability of finding leads for drug discovery. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2001;41:856–864. doi: 10.1021/ci000403i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansch C, Kurup A. QSAR of chemical polarizability and nerve toxicity. 2. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2003;43:1647–1651. doi: 10.1021/ci030289e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariono M, Kamarulzaman EE, Wahab HA (2014) Computational design of dengue type-2 NS2B/NS3 protease inhibitor: 2D/3D QSAR of quinoline and its molecular docking. In: 3rd international conference on computation for science and technology (ICCST-3). 10.2991/iccst-15.2015.13

- Heller S, McNaught A, Stein S, Tchekhovskoi D, Pletnev I. InChI—the worldwide chemical structure identifier standard. J Cheminform. 2013;5(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav A, Ezhilarasan V, Prakash Sharma O, Pan A. Clostridium-DT (DB): a comprehensive database for potential drug targets of Clostridium difficile. Comput Biol Med. 2013;43(4):362–367. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin CY, Park C, Hwang HJ, Kim GY, Choi BT, Kim WJ, Choi YH. Naringenin up-regulates the expression of death receptor 5 and enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis in human lung cancer A549 cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55(2):300–309. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung UJ, Lee MK, Jeong KS, Choi MS. The hypoglycemic effects of hesperidin and naringin are partly mediated by hepatic glucose-regulating enzymes in C57BL/KsJ-db/db mice. J Nutr. 2004;134(10):2499–2503. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.10.2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny PW, Montanari CA. Inflation of correlation in the pursuit of drug-likeness. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2013;27(1):1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10822-012-9631-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EK, Kwon KB, Song MY, Han MJ, Lee JH, Lee YR, Lee JH, Ryu DG, Park BH, Park JW. Flavonoids protect against cytokine-induced pancreatic beta-cell damage through suppression of nuclear factor kappaB activation. Pancreas. 2007;35(4):e1–e9. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0b013e31811ed0d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Lepp Z, Kawai Y, Terao J, Chuman H. An integrated database of flavonoids. BioFactors. 2006;26(3):179–188. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520260303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolte BS, Londhe SR, Solanki BR, Gacche RN, Meshram RJ. FilTer BaSe: a web accessible chemical database for small compound libraries. J Mol Graph Model. 2018;80:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2017.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JM, Che CT, Lau CB, Leung PS, Cheng CH. Inhibition of intestinal and renal Na+-glucose cotransporter by naringenin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38(5–6):985–995. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46(1–3):3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loharch S, Bhutani I, Jain K, Gupta P, Sahoo DK, Parkesh R (2015) EpiDBase: a manually curated database for small molecule modulators of epigenetic landscape. Database (Oxford) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ma L, Peng H, Li K, Zhao R, Li L, Yu Y, Wang X, Han Z. Luteolin exerts an anticancer effect on NCI-H460 human non-small cell lung cancer cells through the induction of Sirt1-mediated apoptosis. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12(3):4196–4202. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin YC. A bioavailability score. J Med Chem. 2005;48(9):3164–3170. doi: 10.1021/jm0492002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Gonzalez AI, Díaz-Sánchez ÁG, de la Rosa LA, Bustos-Jaimes I, Alvarez-Parrilla E. Inhibition of a-amylase by flavonoids: structure activity relationship (SAR) Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2019;206:437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2018.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshram RJ, Bagul KT, Pawnikar SP, Barage SH, Kolte BS, Gacche RN. Known compounds and new lessons: structural and electronic basis of flavonoid-based bioactivities. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2019;5:1–17. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2019.1597770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Boyle NM, Banck M, James CA, Morley C, Vandermeersch T, Hutchison GR. Open Babel: an open chemical toolbox. J Cheminform. 2011;3(1):33. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oprea TI. Property distribution of drug-related chemical databases. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2000;14(3):251–264. doi: 10.1023/a:1008130001697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oprea TI, Davis AM, Teague SJ, Leeson PD. Is there a difference between leads and drugs? A historical perspective. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2001;41(5):1308–1315. doi: 10.1021/ci010366a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanisamy N, Viswanathan P, Anuradha CV. Effect of genistein, a soy isoflavone, on whole body insulin sensitivity and renal damage induced by a high-fructose diet. Ren Fail. 2008;30(6):645–654. doi: 10.1080/08860220802134532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda S, Kar A. Apigenin (4′,5,7-trihydroxyflavone) regulates hyperglycaemia, thyroid dysfunction and lipid peroxidation in alloxan-induced diabetic mice. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2007;59(11):1543–1548. doi: 10.1211/jpp.59.11.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil KK, Gacche RN. Inhibition of glycation and aldose reductase activity using dietary flavonoids: a lens organ culture studies. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;98:730–738. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.01.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil KK, Meshram RJ, Gacche RN. Effect of monohydroxylated flavonoids on glycation-induced lens opacity and protein aggregation. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2016;31(sup1):148–156. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2016.1180593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitjean M. Applications of the radius-diameter diagram to the classification of topological and geometrical shapes of chemical compounds. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 1992;32:331–337. [Google Scholar]

- Pu P, Gao DM, Mohamed S, Chen J, Zhang J, Zhou XY, Zhou NJ, Xie J, Jiang H. Naringin ameliorates metabolic syndrome by activating AMP-activated protein kinase in mice fed a high-fat diet. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;518(1):61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramteke P, Yadav UCS. Hesperetin, a Citrus bioflavonoid, prevents IL-1β-induced inflammation and a cell proliferation in lung epithelial A549 cells. Indian J Exp Biol. 2019;57:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rao N. In graph theory. In: Forsythe G, editor. Basic graph theory. New Delhi: Prentice Hall; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rengasamy KRR, Khan H, Gowrishankar S, Lagoa RJL, Mahomoodally FM, Khan Z, Suroowan S, Tewari D, Zengin G, Hassan STS, Pandian SK. The role of flavonoids in autoimmune diseases: therapeutic updates. Pharmacol Ther. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V, Goswami R, Madan AK. Eccentric connectivity index: a novel highly discriminating topological descriptor for structure-property and structure-activity studies. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 1997;37:273–282. [Google Scholar]

- Shi LM, Fan Y, Myers TG, O’Connor PM, Paull KD, Friend SH, Weinstein JN. Mining the NCI anticancer drug discovery database: genetic function approximation for the QSAR study of anticancer ellipticine analogues. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 1998;38:189–199. doi: 10.1021/ci970085w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoki H, Tanimae A, Endo S, Matsunaga T, Furuta T, Ichihara K, Ikari A. Kaempherol and luteolin decrease claudin-2 expression mediated by inhibition of stat3 in lung adenocarcinoma a549 cells. Nutrients. 2017;9(6):597. doi: 10.3390/nu9060597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thangapandian S, John S, Lee KW. Genetic function approximation and bayesian models for the discovery of future HDAC8 inhibitors. IBC. 2011;3(15):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Tian T, Li J, Li B, Wang Y, Li M, Ma D, Wang X. Genistein exhibits anti-cancer effects via down-regulating FoxM1 in H446 small-cell lung cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(5):4137–4145. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1542-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tungmunnithum D, Thongboonyou A, Pholboon A, Yangsabai A. Flavonoids and other phenolic compounds from medicinal plants for pharmaceutical and medical aspects: an overview. Medicines (Basel) 2018;5(3):93. doi: 10.3390/medicines5030093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valsecchi AE, Franchi S, Panerai AE, Rossi A, Sacerdote P, Colleoni M. The soy isoflavone genistein reverses oxidative and inflammatory state, neuropathic pain, neurotrophic and vasculature deficits in diabetes mouse model. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;650(2–3):694–702. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veber DF, Johnson SR, Cheng HY, Smith BR, Ward KW, Kopple KD. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J Med Chem. 2002;45(12):2615–2623. doi: 10.1021/jm020017n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Huang S. Fisetin inhibits the growth and migration in the A549 human lung cancer cell line via the ERK1/2 pathway. Exp Ther Med. 2018;15(3):2667–2673. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.5666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan A, Gasteiger J. Prediction of aqueous solubility of organic compounds based on a 3D structure representation. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2003;43:429–434. doi: 10.1021/ci025590u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Engkvist O, Llinàs A, Chen H. Beyond size, ionization state, and lipophilicity: influence of molecular topology on absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity for druglike compounds. J Med Chem. 2012;55(8):3667–3677. doi: 10.1021/jm201548z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Chang DT, Grulke CM, Tan YM, Goldsmith MR, Velez RT. Essential set of molecular descriptors for ADME prediction in drug and environmental chemical space. Research. 2014;1:996. [Google Scholar]

- Yin H, Huang L, Ouyang T, Chen L. Baicalein improves liver inflammation in diabetic db/db mice by regulating HMGB1/TLR4/NF-?B signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;55:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalden P, Song L, Wu X, Huang H, Ahr F, Mücke OD, Reichert J, Thorwart M, Mishra PK, Welsch R, Santra R, Kärtner FX, Bressler C. Molecular polarizability anisotropy of liquid water revealed by terahertz-induced transient orientation. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2142. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04481-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Abraham M, Zissimos A. Fast calculation of van der Waals volume as a sum of atomic and bond contributions and its application to drug compounds. J Org Chem. 2003;68:7368. doi: 10.1021/jo034808o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]