Abstract

The viability of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) depends on energy generated by its respiratory chain. Cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase and type-2 NADH dehydrogenase (NDH-2) are respiratory chain components predicted to be essential, and are currently targeted for drug development. Here we demonstrate that an Mtb cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase deletion mutant is viable and only partially attenuated in mice. Moreover, treatment of Mtb-infected marmosets with a cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase inhibitor controls disease progression and reduces lesion-associated inflammation, but most lesions become cavitary. Deletion of both NDH-2 encoding genes (Δndh-2 mutant) reveals that the essentiality of NDH-2 as shown in standard growth media is due to the presence of fatty acids. The Δndh-2 mutant is only mildly attenuated in mice and not differently susceptible to clofazimine, a drug in clinical use proposed to engage NDH-2. These results demonstrate the intrinsic plasticity of Mtb’s respiratory chain, and highlight the challenges associated with targeting the pathogen’s respiratory enzymes for tuberculosis drug development.

Subject terms: Target validation, Antibacterial drug resistance, Bacterial genetics, Pathogens

New tuberculosis therapies, targeting respiratory chain components of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, are under development. Here the authors show that, contrary to common belief, some of these components are not essential for pathogen viability and/or virulence in animal models of infection.

Introduction

In 2012, bedaquiline (BDQ) became the first new drug approved for treatment of tuberculosis (TB) in ~40 years1. The proposed mode of action of BDQ entails a perturbation of Mtb’s ATP synthase causing lethal proton cycling2. To function, ATP synthase activity requires proton motive force (pmf) created by the respiratory chain (RC), which in Mtb consists of nine respiratory dehydrogenases and four terminal oxidoreductases3. Maintenance of pmf is essential for Mtb’s viability in replicative and non-replicative states4, which highlights Mtb’s RC as a promising cell process for drug development. Two RC components were predicted to be essential for optimal growth of Mtb, namely the cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase, encoded by ctaB, ctaC, ctaD, and ctaE-qcrCAB, and a type-2 NADH dehydrogenase (NDH-2) encoded by two genes, ndh and ndhA5–7. Recently, ndh was shown to be dispensable for growth of Mtb8, but a mutant devoid of NDH-2 activity - due to deletion of both ndh and ndhA - was predicted to be not viable8.

Cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase and NDH-2 also seem susceptible to inhibition by drug-like molecules and are being pursued as targets for TB drug development. Several groups have identified imidazopyridine amides that likely target QcrB9–11. Most notably, Q203, an imidazopyridine amide, was originally reported to be efficacious in the mouse model of TB10, and it is currently being evaluated in clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02530710; NCT02858973; NCT03563599). Most recently, the arylvinylpiperazine amides were described as a new class of potent QcrB inhibitors12. NDH-2 has been proposed as the molecular target of several potent antimycobacterial compounds including the phenothiazines13 and is thought to activate clofazimine (CFZ)14, a drug that has been used to treat leprosy for decades and is occasionally included in the treatment of multi-drug resistant (MDR) TB. Other compounds with antimycobacterial activity that have been reported to inhibit NDH-2 include quinolinyl pyrimidines15, compounds with a tetrahydroindazole or a thioquinazoline core16, and 2-mercapto-quinazolinones17. Furthermore, it has been shown that quinolinequinones are bactericidal due to an activation of NDH-2 activity18. This is consistent with a report indicating that activation of the respiratory chain can accelerate the cidality of TB drugs19.

It is, nevertheless, not obvious why Mtb should require either cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase or NDH-2 to grow. The Mtb genome encodes an alternative, oxygen-dependent respiratory oxidoreductase, the cytochrome bd oxidase, which can compensate for the loss of the cytochrome bc1-aa3 in M. smegmatis20 and Mtb, suggesting that Q203 might not be able to prevent growth of Mtb in mice, unless cytochrome bd oxidase is also inhibited21. It was furthermore shown that electrons can be re-routed by Mtb to cytochrome bd oxidase when cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase is inhibited22. Cytochrome bd oxidase is strongly upregulated in hypoxia suggesting that essentiality of either system may be dependent upon oxygen tension23,24. To integrate the somewhat contradictory data on essentiality of cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase, it has been proposed that cytochrome bd oxidase is sufficient to maintain cell viability when cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase is not functional, but it is incapable of sustaining growth of Mtb21. The predicted essentiality of NDH-2 activity is surprising because Mtb can express a type-1 NADH dehydrogenase (NDH-1), which is similar to the eukaryotic respiratory complex 1 and thus could, at least in principle, compensate for the loss of NDH-2 activity3.

Here, we combine conditional gene silencing, chemical genetics, and treatment efficacy studies to determine the consequences of inhibiting Mtb’s cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase or NDH-2 in vitro and during infections of mice and marmosets.

Results

The cytochrome bc1-aa3 and bd oxidases of Mtb are redundant

We constructed three TetOFF mutants, in which anhydrotetracycline (atc) represses expression of ctaE-qcrCAB, ctaC, and ctaD, respectively. Atc reduced the growth rate of these mutants, but it did not prevent their growth (Supplementary Fig. 1A–C), supporting the hypothesis that inactivation of the bc1-aa3 complex might not prevent growth of Mtb. This conclusion was confirmed by isolating deletion mutants for ctaE-qcrCAB, ctaC, and ctaD. These mutants grew with rates similar to those observed after silencing cytochrome bc1-aa3 subunits by the TetOFF system (Supplementary Fig. 1D–F). Deletion of the targeted genes was confirmed by whole genome sequencing (WGS), which also allowed the screening for possible secondary mutations (Supplementary Fig. 2, and Supplementary Table 1). None of the mutants carried additional mutations predicted to impact growth and genetic complementation rescued the slow growth phenotype of all deletion mutants.

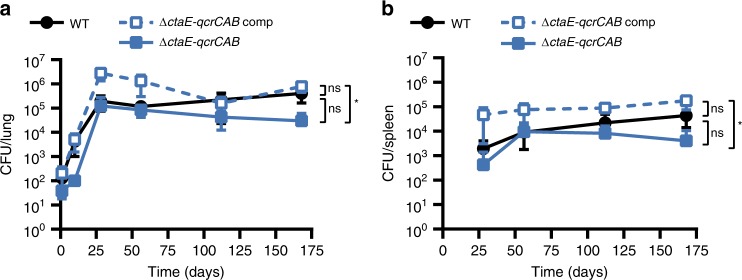

In mice ΔctaE-qcrCAB grew slowly during the acute phase of infection, but by day 28 post infection the strain had reached the same titer as wild-type Mtb (WT) and showed no pronounced persistence defect thereafter (Fig. 1). ΔctaC presented an even slower growth rate than ΔctaE-qcrCAB, reaching maximum titers in the lung at day 56 (~1 log lower than the WT), and in spleens at day 112 (~1 log lower than the WT) (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

The cytochrome bc1-aa3 complex is dispensable for growth and persistence of Mtb in mice. Growth and persistence of ΔctaE-qcrCAB in mouse lungs (a) and spleens (b). Data are averages of CFUs from at least three mice per time point. Error bars correspond to standard deviation. “Comp” stands for complemented. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc test (Tukey test; GraphPad Prism). *P < 0.05; ns - not significant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

To understand the mechanisms that allow Mtb to grow in the absence of cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase, we analyzed the mRNA levels of nuoA (NDH-1), ndh and ndhA (NDH-2), ctaC (cytochrome aa3 oxidase), qcrA (cytochrome bc1 reductase), cydA (cytochrome bd oxidase), and atpE (ATP synthase) from cultures grown to mid-exponential phase in standard media (Supplementary Fig. 4A–D). Ndh and cydA were both consistently upregulated in response to genetic inactivation of cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase. Induction of cydA, which also occurred in response to treatment of Mtb with Q20311, suggested that elevated expression of the cytochrome bd oxidase compensated for the lack of cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase. We therefore constructed Mtb ΔcydABDC ctaE-qcrCAB-TetOFF which allowed us to conditionally silence ctaE-qcrCAB in a cytochrome bd oxidase deletion mutant (Supplementary Fig. 5). ΔcydABDC ctaE-qcrCAB-TetOFF did not grow after silencing of ctaE-qcrCAB with atc in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 1G). Doxycycline (doxy), which is used to regulate Mtb gene expression during animal infection, had a drastic impact on this strain in mice (Supplementary Fig. 6A, B). When doxy was administered from day 1, the strain was unable to establish infection; when administered from day 35, CFU decreased by approximately five orders of magnitude over the next 35 days. As reported previously21, we observed no growth or persistence defects for ΔcydABDC, in which only the cytochrome bd oxidase was inactivated (Supplementary Fig. 1H, Supplementary Fig. 6C, D). In summary, these data demonstrate that Mtb requires the cytochrome bc1-aa3 supercomplex to achieve optimal growth rates and maximal titers in mice, but this RC complex is not essential for growth or persistence as long as Mtb can express cytochrome bd oxidase.

ND-10885 controlled infection, but increased cavitation

The findings described above raised concerns about the use of cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase inhibitors as stand-alone drugs to treat TB, adding to a previous report showing that Q203 alone was not able to stop Mtb’s growth in mice21. It is, however, worth noting that Q203 might synergize in vivo with approved TB drugs, such as rifampicin or pyrazinamide25, thus being a possible suitable candidate for combination therapies. We therefore sought to determine efficacy of a cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase inhibitor in an animal model that reproduces more aspects of human TB pathogenesis than the mouse model.

TB disease includes a broad spectrum of lesion types that evolve in response to host attempts to limit the infection. These lesion types present Mtb with a variety of different carbon sources to be metabolized under a range of oxygen tensions26. Hence, we selected a non-human primate model of TB disease in common marmosets27,28 to test Q203 efficacy. Initial experiments with Q203 failed to produce a formulation that gave acceptable exposure in these monkeys. A structural analog of Q203 (Supplementary Fig. 7) with improved pharmacokinetics and solubility properties (ND-10885)29, with an MIC of 0.1 μM against CDC1551, the Mtb strain used for infection of marmosets, was therefore employed and found to give good exposure in marmosets following oral administration with co-administration of a CYP450 inhibitor, 1-aminobenzotriazole (ABT)30,31 (Supplementary Figs. 8A and 9). Tissue distribution studies in lung lesion compartments revealed adequate concentrations in all lesions and favorable partitioning in laser-captured necrotic foci and cavity caseum (Supplementary Fig. 8B–D).

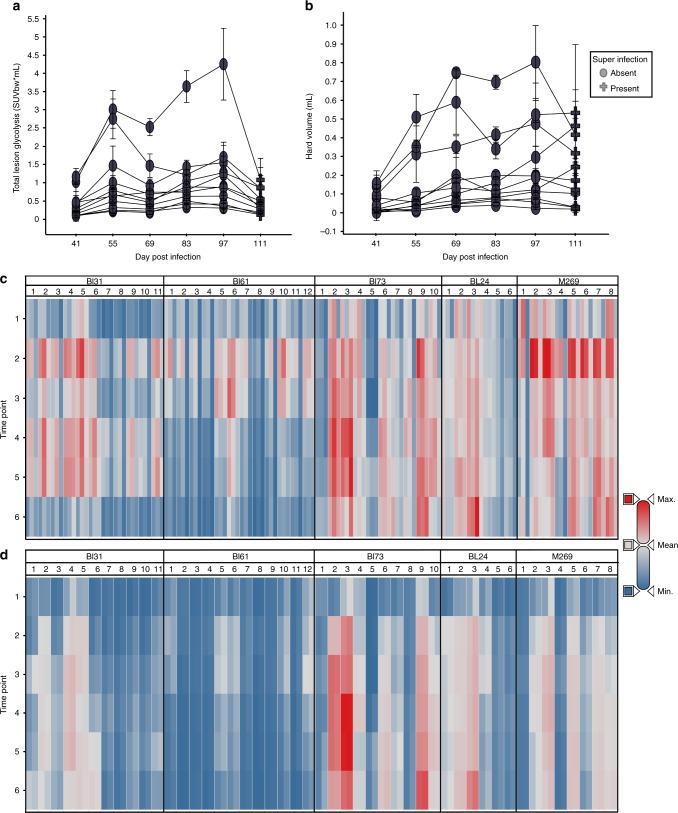

Marmosets were infected by low-dose aerosol and disease development was monitored by bi-weekly 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (FDG) PET-CT scanning as previously described28. After 50–55 days of infection, moderate to large lesions were clearly visible in these animals by PET-CT imaging and treatment with ND-10885 was initiated. Disease progression was arrested by treatment as illustrated in Fig. 2a, which shows the total uptake of FDG for each of the individual lesions in a single animal. Figure 2b shows the total volume of each lesion within the range of –100 to 200 Hounsfeld Units, which we have previously shown represents the majority of radiodense tissue associated with TB lesions28. Figure 2c, d show heat maps of those same two parameters for all five animals illustrating that most lesions within these animals showed reduced FDG uptake, indicating reduced inflammation, while maintaining a consistent volume of hard lesion density.

Fig. 2.

ND10885 treatment of M. tuberculosis infected marmosets. a Total lesion glycolysis within each individual lesion for a single animal. The timeline begins 41 days post-infection and treatment within this animal begins at Day 55. Most lesions appear to become less FDG avid within the first 2 weeks of treatment and then stabilize or progress for 2-month treatment period. In untreated animals all lesions would have continued to progress. Symbols represent the mean and error bars of the standard deviation of three independent readers. b Hard lesion volume (−100 HU to +200 HU) in most lesions the volume growth slows when treatment starts but it is maintained at the same level as the last pretreatment scan (Day 55). Symbols represent the mean and error bars the standard deviation of three independent readers. c Heat map of the lesion-level total PET data for all five animals that were treated with ND10885. Timepoint 2 is the equivalent of Day 55 in panels (a) and (b), the starting point of drug administration. Most lesions in these animals behave in the same way as those shown in panel (a), the total inflammation in each decreases from timepoint 2 to the end of therapy. For each lesion the three bars represent SUVmax, SUVmean and total lesion glycolysis. d The lesional volume change in each lesion for all animals across the same treatment period. Again similar to the pattern shown in panel (b) volume plateaus in most lesions at timepoint 3, 2 weeks after the initiation of treatment. For each lesion two bars are shown, the left bar indicates volume in the hard range (−100 to + 200 HU) while on the right the total lesion volume (from −500 to + 200 HU) is shown. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

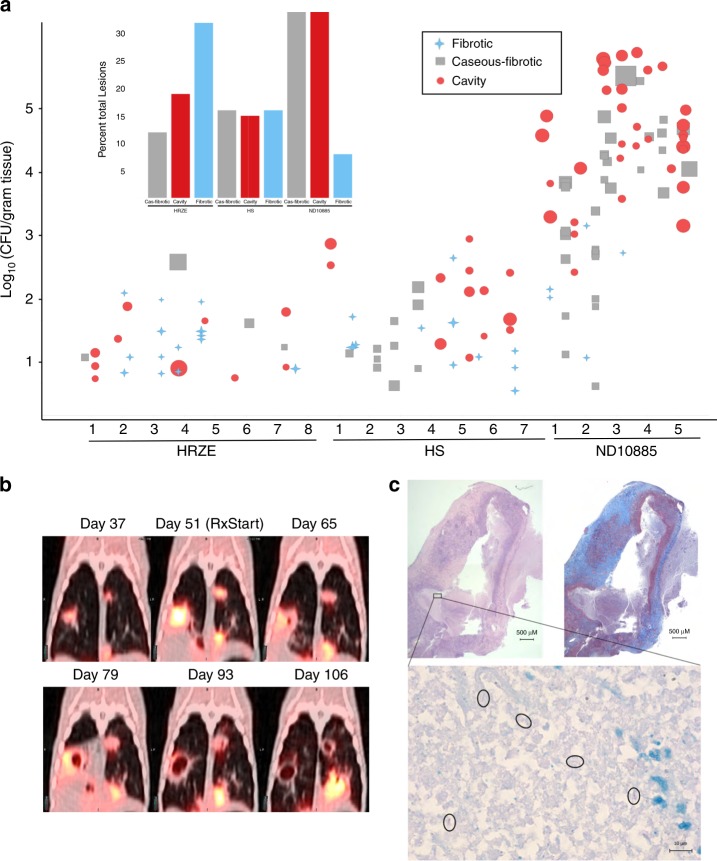

After 2 months of treatment, animals were humanely killed and individual lesions were dissected for enumeration of bacterial CFU and detailed histology. The CFU and gross pathology results are shown in Fig. 3 in comparison with two other treatment regimens previously reported: the standard care treatment for TB patients isoniazid-rifampicin-pyrazinamide-ethambutol (HRZE), and an earlier 2-year regimen associated with unacceptable relapse rates in TB patients that comprised streptomycin-isoniazid (HS)28. CFU and lesion numbers were substantially higher in the animals treated with ND-10885 compared with a two-month treatment with either HRZE, or HS. None of the bacteria recovered from the infected animals were resistant to ND-10885 (Supplementary Table 2). Most strikingly, as illustrated by the shape of the symbols in Fig. 3a, approximately half of lesions were characterized as cavitary on the basis of gross pathology in animals treated with ND-10885 (inset is the comparison of the gross pathology findings by treatment arm for all three treatments). Histological examination of these lesions revealed that nearly all lesions had a well-developed fibrous cuff surrounding a central area of necrosis. Lesions characterized as “caseous-fibrotic” at gross pathology appear to be identical to cavities that had not yet liquefied and drained into the airways. Figure 3b displays the PET/CT findings from one of these animals and shows the development and drainage of the liquefied interior into the airways during treatment with ND-10885. Finally, Fig. 3c shows the histopathology of the cavity from the left superior lung lobe cavity shown in Fig. 3b revealing a large, partially liquefied lesion with areas of caseous necrosis surrounded by a dense fibrotic cuff. This 8-mm lesion contained ~224,000 bacteria and these bacteria were easily observable within the necrotic region of the lesion by acid-fast staining (Fig. 3c, lower panel). Taken together, these data demonstrate that treatment with Mtb’s cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase inhibitor ND-10885 effectively controlled the infection in that no new lesions appeared and inflammation was reduced, but only a subset of organisms was affected while those present in existing granulomas flourished resulting in exacerbation of disease by increasing cavitation.

Fig. 3.

ND10885 treatment in infected marmosets allows cavity formation. a Lesion pathology at necropsy for marmosets treated with three different drug regimens. HRZE, isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol; HS, isoniaizid, and streptomycin (CFU data and PK have been previously published for both control arms; ref. 28). Each number refers to an individual animal and each symbol above it describes the pathology of each individual lesion within that animal, the size of the symbol is according to the size of the lesion, small symbols are 1 mm lesions and the largest symbols are ~10 mm lesions. The inset bar graph summarizes the same data according to the total percentage of lesions in each of the three pathology types. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. b an example of PET/CT images of one animal treated with ND10885 over time, the first image is 37 days after infection with a low-dose aerosol of M. tuberculosis, the second image is day 51 and immediately after that image the animal began receiving ND10885. There are two lesions, one on the right and one on the left that progressively cavitate and expel their contents. c Pathology images of one of these cavities showing on the top left the H&E stained slice and on the right the Masson’s Trichrome stain to illustrate the fibrous cavity wall. In both panels the scale bar is 500 μm. The small black box in the H&E slice is shown at ×100 with a 10-μm scale bar with acid-fast staining showing the presence of multiple individual bacilli (circled)

Essentiality of NDH-2 is conditional

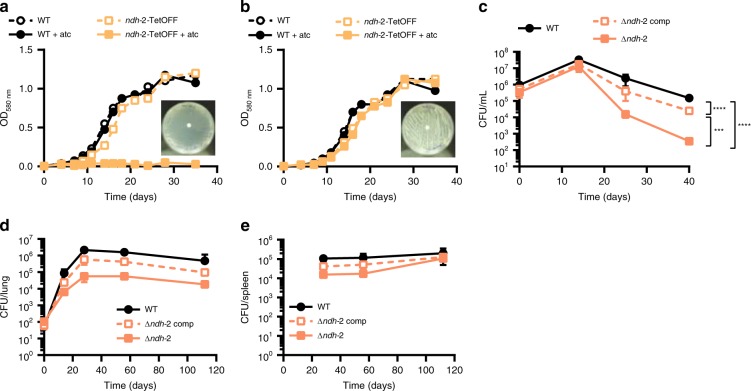

Besides cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase, NDH-2 is the second component of Mtb’s RC that is considered as a target for TB drug development. However, efforts to utilize its inhibition might be plagued by the same functional redundancy that affects inhibition of cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase. The Mtb genome can express two NDH-2 enzymes, encoded by ndh and ndhA, and one NDH-1, encoded by the nuo operon3. To evaluate the consequences of inhibiting both NDH-2 enzymes we constructed Mtb ndh-2-TetOFF, in which ndh has been deleted and ndhA can be silenced with atc. ndh-2-TetOFF did not grow in standard liquid and solid media containing atc (Fig. 4a). Surprisingly, atc had no effect on ndh-2-TetOFF in minimal media devoid of fatty acids (Fig. 4b). We confirmed that essentiality of NDH-2 is conditional using fatty-acid-free media by isolating Mtb Δndh-2, in which ndh and ndhA have both been deleted. Deletion of both NDH-2 encoding genes was confirmed by WGS (Supplementary Fig. 10). Transformation with an intact copy of ndh rescued Δndh-2 (see below), which suggests that the polymorphisms identified in Δndh-2 (Supplementary Table 1) are not responsible for the phenotypes of Δndh-2. Δndh-2 grew like WT in liquid media without fatty acids, but survival was compromised during gradual oxygen depletion (Fig. 4c). In mouse lungs, Δndh-2 grew to titers that were, on average, 26-fold lower than for WT (Fig. 4d). The mutant was less attenuated in spleens (Fig. 4e).

Fig. 4.

NDH-2 is essential for growth with fatty acids. Growth with (a) or without fatty acids (b). Data are representative of two independent experiments. c Growth and survival in the Wayne model of hypoxia. Data are averages of six to eight data points from two independent experiments. Growth and persistence in lungs (d) and spleens (e) of C57BL/6 mice. Data are averages from four mice per time point and representative of two independent infections. Error bars correspond to standard deviation. “Comp” stands for complemented. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc test (Tukey test; GraphPad Prism). Differences between strains in (d) and (e) are not significant. ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

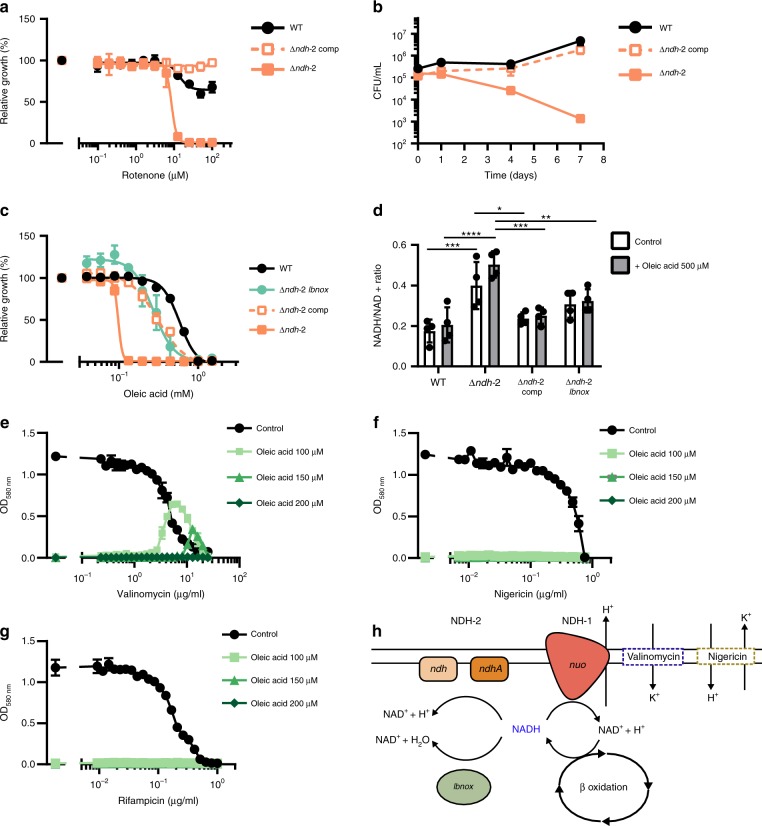

To assess for possible compensatory effects to the lack of a functional NDH-2 enzyme we analyzed the transcripts levels of nuoA, ndh, ndhA, qcrA, ctaC, cydA, and atpE in cultures grown to mid-exponential phase in fatty-acid-free modified Sauton’s media. Apart from the expected absence of ndh and ndhA transcripts in Δndh-2, we did not observe differences between the mutant and the WT (Supplementary Fig. 4E, F). To test if Δndh-2 is viable due to compensation by NDH-1 we determined susceptibility of Δndh-2 to the NDH-1 inhibitor rotenone. Rotenone was inactive against WT Mtb, which agrees with previous data;4 but rotenone prevented growth of and was bactericidal for Δndh-2 (Fig. 5a, b). We conclude that NDH-1 and NDH-2 are functionally redundant and inhibition of both kills Mtb regardless of the presence of fatty acids.

Fig. 5.

NDH-2 is required for redox homeostasis and counteracts inhibition of NDH-1. a Impact of rotenone on growth. b Survival in fatty-acid-free Sauton’s minimal medium supplemented with 50 μg/mL rotenone. c Impact of oleic acid on growth. (d) NADH/NAD + intracellular ratio after 6 h in modified Sauton’s minimal medium supplemented with DMSO (1%, control), or oleic acid (500 μM). Impact of valinomycin (e), nigericin (f), and rifampicin (g) on growth in modified Sauton’s minimal medium supplemented with DMSO (1%; control), or oleic acid at different concentrations (100 μM, 150 μM, and 200 μM). h Proposed mechanism of NDH-2 essentiality in the presence of fatty acids. Data are averages of three data points and representative of at least two independent experiments. Error bars correspond to standard deviation. “Comp” stands for complemented. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc test (Tukey test; GraphPad Prism). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

We next sought to understand why fatty acids were toxic for Δndh-2. Δndh-2 was hypersusceptible to oleic acid (C18:1), palmitic acid (C16:0), and octanoic acid (C8:0), yet butyric acid showed only mild toxicity and Δndh-2 grew normally with acetate and cholesterol (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Fig. 11). Fatty acid toxicity was thus dependent on chain length, with longer fatty acids being more toxic. This suggested that NDH-2 might be needed to balance the ratio of NADH to NAD+, similar to the function energy dissipating respiratory enzymes have during aerobic growth with highly reduced carbon sources in other bacteria32,33. To test this, we expressed LbNox (Supplementary Fig. 12), an NADH oxidase which converts NADH into NAD+ and water34, in Δndh-2. LbNox reduced sensitivity of Δndh-2 to oleic acid to the same extent as ectopic expression of Ndh (Fig. 5c). When we measured NADH and NAD+, we found the NADH/NAD+ ratio to be higher in Δndh-2 than in WT Mtb (Fig. 5d). Complementation with ndh and expression of LbNox reduced the NADH/NAD+ ratio of Δndh-2 to a level similar to that of WT. However, the NADH/NAD+ ratio of Δndh-2 was high with and without fatty acids and oleic acid did not cause NADH to accumulate further (Fig. 5d). The latter argued against fatty acid toxicity being a consequence of an imbalance in NADH/NAD+ in Δndh-2. We reasoned that accumulation of NADH after exposure to oleic acid was prevented by NDH-1.

In contrast to NDH-2, consumption of NADH by NDH-1 is linked to the export of protons. Sole reliance on NDH-1 might thus cause an excessive accumulation of periplasmatic protons in the presence of fatty acids and increase proton motif force (pmf) to levels that inhibit growth. To test this hypothesis, we used valinomycin or nigericin, which can reduce pmf by abrogating the membrane potential and ΔpH, respectively. A narrow range of valinomycin concentrations indeed supported growth of Δndh-2 with oleic acid. In contrast, no effect was observed with nigericin or rifampicin (Fig. 5e, f, g). This suggested that a deregulation of the membrane potential and consequently of pmf causes the oleic acid sensitivity of Δndh-2 (Fig. 5h).

Drug susceptibility profiles

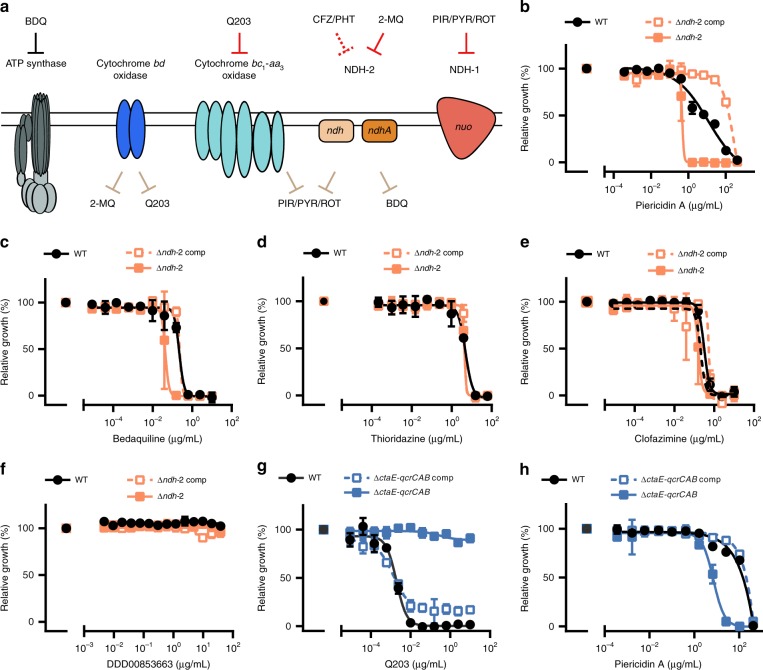

NDH-2 and cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase have been proposed as the targets for several small molecules with antitubercular activity (Fig. 6a). To determine how genetic inactivation of NDH-2 and terminal oxidases affects drug susceptibility of Mtb we profiled ΔctaE-qcrCAB, ΔcydABDC, and Δndh-2 with (i) the TB drugs rifampicin, isoniazid, ethionamide, and ethambutol; (ii) compounds targeting NDH-1 (rotenone, ROT; piericidin A, PIR; pyridaben, PYR), the ribosome (linezolid), DNA gyrase (ciprofloxacin), ATP synthase (bedaquiline, BDQ), and cytochrome bc1 reductase (Q203); (iii) compounds proposed to target NDH-2 (CFZ, three phenothiazines (chlorpromazine, CPZ; trifluoperazine, TFP; thioridazine, TRZ), and two 2-mercapto-quinazolinones (DDD00853663, DDD00946831, which correspond to compounds 7 and 10 in the work that first described them – Supplementary Fig. 1317); and (iv) the ionophore valinomycin. Susceptibility to rifampicin, isoniazid, ethionamide, ethambutol, linezolid, and valinomycin was similar for all strains (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4), demonstrating that none of the mutants had an unspecific drug susceptibility defect. Q203 was more potent against ΔcydABDC than WT (Supplementary Fig. 14A), which is in agreement with previous reports11,21,35. Q203 showed no activity against ΔctaE-qcrCAB (Fig. 6g). At least in standard media, Q203 has thus no phenotypically relevant target other than cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase. ΔctaE-qcrCAB, but not ΔcydABDC, proved to be hypersusceptible to NDH-1 inhibitors (Fig. 6h, Supplementary Fig. 14B–D, G, H).

Fig. 6.

Chemical–genetic interactions. a Summary of chemical–genetic interactions. Red lines represent direct interactions that are consistent (solid red lines) or inconsistent (dotted red lines) with the chemical–genetic interactions defined in this study. Brown lines represent chemical–genetic interactions that have been defined in this study and are most likely indirect. Impact of piericidin A (b, h) bedaquiline (c) thioridazine (d), clofazimine (e), DDD00853663 (f), and Q203 (g) on growth. Data are averages of three cultures and represent at least two independent experiments. Error bars correspond to standard deviation. BDQ, bedaquiline; CFZ, clofazimine; PHT, phenothiazines; PIR, piericidin A; PYR, pyridaben; ROT, rotenone; 2-MQ, 2-mercapto-quinazolinones. “Comp” stands for complemented. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

2-mercapto-quinazolinones have recently been described as inhibitors of NDH-217. We found 2-mercapto-quinazolinones to be potent against WT when oleic acid was present in the media, yet inactive against WT and Δndh-2 (Fig. 6F, Supplementary Figs. 14O and 15E, F) in fatty-acid-free media. Chemical and genetic inhibition of NDH-2 thus lead to similar phenotypes. Interestingly, both 2-mercapto-quinazolinones were also more active against ΔcydABDC than WT, which suggests that the inactivation of both cytochrome bd oxidase and NDH-2 synergize to inhibit Mtb’s growth (Supplementary Fig. 14E, F). The effect of these compounds on ΔctaE-qcrCAB growth was negligible (Supplementary Fig. 14I, J). Δndh-2 was furthermore hypersusceptible to all NDH-1 inhibitors and BDQ (Fig. 6b, c, Supplementary Fig. 14K, L). However, inactivation of NDH-2 had little, if any, effect on the phenothiazines and CFZ (Fig. 6d, e, Supplementary Fig. 14M, N). CFZ and phenothiazines also had similar activities in the presence and absence of oleic acid (Supplementary Fig. 15A–D). We concluded that CFZ does not require activation by NDH-2 to prevent growth of Mtb and that NDH-2 is not the primary, growth-limiting target of the phenothiazines.

Discussion

We draw three main conclusions from this work. First, inactivation of Mtb’s cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase alone is insufficient to kill Mtb and could possibly complicate treatment by increasing cavity formation. Complete genetic inactivation of cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase decreased but did not abolish growth of Mtb in vitro and in mice. Viability of Mtb without cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase was dependent on a functional cytochrome bd oxidase. In contrast, inactivation of both cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase and cytochrome bd oxidase rapidly killed Mtb in mice. Marmosets provide an animal model that closely recapitulates human disease27 with frontline chemotherapy following a similar trajectory to sterilization in patients28. Strikingly, 2 months of treatment with the cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase inhibitor ND-10885 reduced inflammation in Mtb-infected marmosets as measured by FDG uptake but caused no discernable reduction in radiodense volume of disease. ND-10885 arrested disease progression but not pathology progression. We have previously demonstrated that efficacious drugs and drug regimens lead to a progressive decline in radiodensity corresponding to granulomatous regions in the lung28,36. Such caseous lesions are severely hypoxic37 and replication of Mtb under these conditions seems unlikely to be dependent upon the cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase targeted by ND-10885. Failure to restrict the growth of these hypoxic bacilli likely leads to progression of disease resulting in cavity formation and high bacterial titers. Our data also suggest that growth of bacteria in cellular lesions and macrophages is restricted as lesion density stabilizes as would be expected if in these microenvironments Mtb was dependent upon the cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase. Correspondingly, ND-10885 had inferior sterilizing ability compared to even sub-therapeutic regimens such as streptomycin/isoniazid. Alarmingly, treatment with ND-10885 led to increased cavitation, a pathology known to be associated with poor treatment outcome38. Whether this increase in cavitation is specific to ND-10885 or will also be caused by other inhibitors of the cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase remains to be determined.

Second, preventing growth of Mtb during infection by targeting its NADH dehydrogenases requires inactivating three enzymes: the two NDH-2 enzymes encoded by ndh and ndhA and the NDH-1 complex encoded by the nuo operon. Previous genetic analysis concluded that Mtb requires at least one NDH-2 enzyme to grow8. Our data agree with this prediction as we found Mtb to require NDH-2 for growth in standard media. Mtb does, however, not require NDH-2 to grow in fatty-acid-free medium or in media containing short-chain fatty acids or cholesterol. In mice, Δndh-2 was attenuated during the acute phase of infection, but it showed no severe persistence defect. The attenuation that results from inactivation of both NDH-2 enzymes is thus not fundamentally different from what has been observed for a mutant missing NDH-1 and one of Mtb’s two NDH-2 enzymes. The activity of specific NDH-2 inhibitors, such as the 2-mercapto-quinazolinones, phenocopy genetic inactivation of NDH-2 in vitro and will thus likely be inefficacious during infection.

Complementation of Δndh-2 oleic acid hypersusceptibility with LbNox indicated that NADH generation contributes to long chain fatty acid toxicity. This can explain why Δndh-2 is less sensitive to short-chain fatty acids and cholesterol, as the full oxidation of these carbon sources require a low number of β-oxidation cycles, while, for example, oleic acid goes through 9 cycles for full oxidation. However, toxicity did not arise from an unbalanced NADH/NAD+ ratio alone. Rescue with valinomycin, but not with nigericin, indicated that a deregulation of the membrane potential was, at least in part, responsible for fatty acid toxicity. Since NDH-1 is the only NADH dehydrogenase operating in Δndh-2, the coupling of NADH oxidation with proton extrusion might have contributed to disturb the membrane potential and consequently pmf.

Third, phenothiazines and CFZ inhibit growth of Mtb independently of NDH-2. Although there is evidence for an effect of phenothiazines on Mtb’s RC4,13, the potency of these compounds does not change in response to inactivation of NDH-2. That phenothiazines act independently of NDH-2 is also supported by the pleiotropic effects that phenothiazines can have, which include an impact on membrane permeability and inhibition of the synthesis of various macromolecules39,40. The growth-inhibitory activity of CFZ is thought to depend on the oxidative stress it causes after reduction by NDH-214. Antioxidants can rescue Mtb’s viability when facing bactericidal CFZ concentrations, which supports this mode of action14. However, WT and Δndh-2 were equally susceptible to CFZ. Clearly, the activity of CFZ is not dependent on NDH-2. Conceivably, CFZ might be reduced by enzymes other than NDH-2, but it is unlikely that NDH-1 is capable of fulfilling this role, since membranes from bacteria that only express NDH-1 did not reduce CFZ14.

After the discovery of BDQ, several complexes of Mtb’s RC were embraced as new targets for TB drug development. This enthusiasm was supported by new small molecules that inhibit the cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase and drugs or drug candidates that engage NDH-2. However, the data presented here suggest that inactivation of either cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase or NDH-2 alone may not improve TB chemotherapy. Combinations of inhibitors targeting either cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase and cytochrome bd oxidase or NDH-2 and NHD-1 will be required to effectively inhibit the respiratory chain of Mtb. In this context, our work further unveiled genetic and chemical–genetic interactions which could be exploited to improve TB chemotherapy, namely the interactions between cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase and NDH-1, NDH-2 and ATP synthase, and NDH-2 and cytochrome bd oxidase. Targeting only cytochrome bc1-aa3 oxidase or NDH-2 might be most valuable for the treatment of infections caused by mycobacteria, such as M. leprae, that do not possess a functional cytochrome bd oxidase or NDH-1. This strategy has been successfully applied to M. ulcerans, which lacks the alternative terminal oxidase41.

Methods

Culture conditions

E scherichia coli was used as host for cloning and cultured in LB. Mtb was generally cultured in Middlebrook 7H9 supplemented with 0.2% glycerol, 0.05% tyloxapol, and ADNaCl (0.5% BSA, 0.2% dextrose and 0.85% NaCl) or in Middlebrook 7H10 supplemented with 0.5% glycerol and 10% oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase (OADC). Fatty acid sensitive strains were cultured in a modified Sauton’s minimal medium (0.05% potassium dihydrogen phosphate, 0.05% magnesium sulfate heptahydrate, 0.2% citric acid, 0.005% ferric ammonium citrate, and 0.0001% zinc sulfate) supplemented with 0.05% tyloxapol, 0.4% glucose, 0.2% glycerol, and ADNaCl with fatty-acid-free BSA (Roche). Fatty-acid-free solid medium contained 1.5% bactoagar (BD) and glycerol was used at a concentration of 0.5%. When necessary, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: apramycin 20 μg mL−1, kanamycin 25 μg mL−1, zeocin 25 μg mL−1, streptomycin 25 μg mL−1, and hygromycin 50 μg mL−1. When needed, atc was used at a concentration of 500 ng mL−1 (ref. 42).

Mutant construction

All mutants were constructed using protocols and procedures described in detail elsewhere43. Briefly, for mutants of ctaE-qcrCAB, we first generated a merodiploid by inserting a plasmid at the att-L5 site that expressed ctaE-qcrCAB under the control of its own promoter (pGMCS-PctaE-qcrCAB). The WT copy of ctaE-qcrCAB was then replaced by a hygromycin resistance cassette using a temperature sensitive plasmid leading to ΔctaE-qcrCAB::PctaE-qcrCAB. In this strain, the only functional copy of ctaE-qcrCAB is located in the attL5 site, where it can be replaced or deleted by site-specific recombination44. To construct ctaE-qcrCAB-TetOFF, pGMCS-PctaE-qcrCAB was replaced with pGMCZ-T38S38-750-ctaE-qcrCAB-SD2, which expresses under control of a reverse TetR; to delete ctaE-qcrCAB, pGMCS-PctaE-qcrCAB was replaced with pGMCZq17-0 × 0 × , which does not contain ctaE-qcrCAB. To complement ΔctaE-qcrCAB the mutant was transformed with pGMCtKq1-PctaE-qcrCAB, which expressed ctaE-qcrCAB under the control of its own promoter after integration into the tweety phage attachment site.

To generate ctaC-tetOFF and ctaD-tetOFF, we have used the dual control (DUC) strategy, which combines repression of transcription and controlled proteolysis to deplete the targeted protein45. First merodiploids were generated by introducing a copy of ctaC under the control of a strong promoter (pGMCS-P750-ctaC-rv2219) or ctaD-serB2 under the operon’s own promoter (pGMCS-PctaD-serB2) into the att-L5 site, the WT loci were replaced by a hygromycin resistance cassette using the phage-mediated recombineering46. These strains were transformed with a plasmid expressing sspB (pGMCtZq17-TSC10M1-sspB) that integrated at the tweety phage attachment site. Next, we swapped the construct at att-L5 with a plasmid where ctaC-DAS or ctaD-DAS are under the control of a Tet-OFF system (pGMCZ-T38S38-750-ctaC-DAS; pGMCZ-serB2(tr)-T38S38-750-ctaD-DAS). In the ctaD-TetOFF mutant, serB2 is expressed constitutively. To generate ΔctaC and ΔctaD, we used ΔctaC::pGMCS-P750-ctaC-rv2219 and ΔctaD::pGMCS-PctaD-serB2, and swapped the construct at the att-L5 site by an empty plasmid (pGMCZq17-0×0×) in the case of ΔctaC, and a plasmid expressing serB2 constitutively (pGMCZ-PserB2) in the case of ΔctaD. Complemented strains were obtained by introducing ctaC under the control of a strong promoter (pGMCtKq1-P750-ctaC), or ctaD under the control of a strong promoter (pGMCtKq1-Puv15-ctaD), at the tweety phage attachment site.

ΔcydABDC was constructed by replacing cydABDC with a hygromycin resistance cassette via homologous recombination. The complemented strain was obtained by expressing cydABDC under its own promoter (pGMCK-PcydABDC-SD1) at the att-L5 attachment site. To construct ΔcydABDC ctaE-qcrCAB-TetOFF, we took advantage of the loxP sites flanking the hygR cassette, which enabled its removal by expression of Cre recombinase, rendering a hygromycin sensitive strain. Using this strain as genetic background, we have followed the strategy previously described to generate a ctaE-qcrCAB-TetOFF strain.

To obtain ndh-2-TetOFF and Δndh-2 we first generated a merodiploid that expressed ndh under its native promoter (pMPa-Pndh) at attL5. We then successively replaced the WT copies of ndh and ndhA with hygromycin and kanamycin resistance cassettes through homologous recombination, respectively, giving rise to Δndh/ndhA::Pndh. The ndh copy in Δndh/ndhA::Pndh was then swapped against a plasmid containing ndhA under the control of the DUC system (pGMCS-0×750-ndhA-DAS)45. The resulting strain transformed with the sspB expressing vector (pGMCtZq17-TSC10M1-sspB) to generate ndh-2-TetOFF. Δndh-2 was obtained by swapping the Pndh plasmid against an empty vector (pGMCZq17-0×0×). The complemented strain was obtained by introducing ndh under the control of a strong promoter (pGMCtSq19-0×-Puv15-ndh) at the tweety phage attachment site. For complementation with LbNOX, a codon usage adapted gene (lbnoxMtb) was ordered from GenScript and cloned into an integrative plasmid (pGMCgS-0×-Ptb38-LbNOX-FLAG-SD1) that inserts at the Giles attachment site. Strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Supplementary Tables 5 and 6.

Whole genome sequencing

The genetic identity of ΔctaE-qcrCAB, ΔctaC, ΔctaD, and Δndh-2 was confirmed by whole genome sequencing (WGS). Between 150 and 200 ng of genomic DNA was sheared acoustically and HiSeq sequencing libraries were prepared using the KAPA Hyper Prep Kit (Roche). PCR amplification of the libraries was carried out for 10 cycles. 5–10 × 106 50-bp paired-end reads were obtained for each sample on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 using the TruSeq SBS Kit v3 (Illumina). Post-run demultiplexing and adapter removal were performed and fastq files were inspected using fastqc (Andrews S. (2010). FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Available at: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc). Trimmed fastq files were then aligned to the reference genome (M. tuberculosis H37RvCO; NZ_CM001515.1) using bwa mem47. Bam files were sorted and merged using samtools48. Read groups were added and bam files de-duplicated using Picard tools and GATK best-practices were followed for SNP and indel detection49. Gene knockouts and cassette insertions were verified for all strains by direct comparison of reads spanning insertion points to plasmid maps and the genome sequence. Reads coverage data was obtained from the software Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV)50–52. Sequencing data was deposited in NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under the BioProject ID PRJNA532433.

Quantitative PCR

Cultures were grown until mid-exponential phase (OD580nm of 0.5) and harvested with GTC buffer. RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and “Quick-RNA™ Miniprep Kit” (Zymo Research), following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was digested with the “Turbo DNA-free kit” (Invitrogen), and 500 μg of RNA were used to synthesize cDNA using M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (New England BioLabs). qPCR reaction was performed with LightCycler® 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche) in the LightCycler® 480 System (Roche). Primers and probes were designed in the software RealTimeDesign™ (Biosearch Technologies), and ordered from TIB MOLBIOL, LLC. The sequences of all primers and probes are available in Supplementary Table 7. Probes for genes of interest were labeled with 5′ 6-FAM/ 3′ BHQ1, while the probe for the reference gene sigA was labeled with 5′ LC670.

Wayne model of hypoxia

Mtb strains were grown in Dubos broth base (Difco) supplemented with 0.05% tyloxapol, 0.75% dextrose, 0.5% fatty-acid-free BSA (Roche), and 0.85% NaCl until mid-log phase (OD580 approx. 0.4). Single cell suspensions were prepared in the same medium to a final OD580 of 0.05. In total, 20 mL of the single-cell suspension were aliquoted into flat-bottomed tubes each equipped with a black cap (Wheaton) and a magnetic stirrer. Paraplast wax (Kendall) was used to seal the tubes. One tube of each strain was further supplemented with methylene blue (1.3 μg mL−1), which served as a hypoxia indicator. Cultures were incubated at 37 °C on a magnetic platform at 130 rpm. OD580 was measured for 40 days and bacteria were plated for CFU at the indicated time points in fatty-acid-free modified Sauton’s medium.

Growth with fatty acids

Strains were grown in modified Sauton’s minimal medium until mid-log phase (OD580 0.6–0.8). Bacteria were collected and resuspended in the same medium to generate single-cell suspensions. Modified Sauton’s minimal medium was supplemented with fatty acids or cholesterol at the following final concentrations: acetic acid 125 mM, butyric acid 25 mM, octanoic acid 2 mM, palmitic acid 500 μM, oleic acid 1 mM (1.5 mM in the assays with lbnox), and cholesterol 125 μg mL−1. Octanoic acid, palmitic acid, and oleic acid were solubilized in DMSO, while cholesterol was solubilized in a 1:1 tyloxapol:ethanol solution and then added to the medium. Serial dilutions of each fatty acid or cholesterol (2-fold) were made in 96-well plates. Single-cell suspension of Mtb strains were added to a final volume in each well of 200 μL and an OD580 of 0.01. Plates were kept at 37 °C and OD580 readings were carried out after 14 days of incubation. Sauton’s minimal medium supplementation with the corresponding solvents at the higher concentration constituted the control and was used to normalize the final OD580 values.

Immunoblot analysis of cytosolic proteins

Protein extracts were prepared from WT, Δndh-2, and Δndh-2::lbnox-Flag cultures. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.05% Tween 80 and resuspended in 500 µL PBS, 1xprotease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Bacterial lysis was performed by bead-beating three times at 4500 rpm for 30 s with 0.1 mm Zirconia/Silica beads. After centrifugation (11,000 × g/10 min, 4 °C), the supernatant was filtered through a 0.2-µm SpinX column (Corning). Protein concentrations were determined using a DC Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad). For immunoblots, 30 µg protein were loaded and separated through SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and incubated with anti-Flag (Sigma-Aldrich; 1∶400 dilution) and anti-PrcB (1∶15,000 dilution). Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences) was used to detect the proteins.

NADH/NAD+ratio determination

Strains were grown in modified Sauton’s minimal medium until an OD580 of 0.5, and resuspended in the same medium supplemented with DMSO or oleic acid (500 μM). Bacteria were harvested after 6 h of further incubation. The NADH/NAD + ratio was determined using the commercial kit Fluoro NAD (Cell Technnology), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein quantification via Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific) was used to normalize NADH and NAD + concentrations.

Drug susceptibility profiling

Depending on the strain, bacteria were cultured in 7H9, modified Sauton’s minimal medium, or modified Sauton’s minimal medium supplemented with oleic acid (200 μM) until mid-log phase (OD580 0.6–0.8) in 100 mL roller bottle cultures. Bacteria were washed once in fresh medium and single-cell suspensions were prepared to a final OD580 nm of 0.01 in the same medium. Compounds were solubilized in DMSO and dispensed into 384-well plates using a D300e Digital Dispenser (HP). DMSO at a final concentration of 1% was used as no-drug control. In all, 50 μL of single-cell suspension was pipetted to each well and cultures were incubated for 12 days at 37 °C. Final OD580 values were normalized to no-drug control.

Mouse infection

All mouse experiments were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health, with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Weill Cornell Medicine. Female C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Labs) were infected with ~100–200 CFU/mouse using an Inhalation Exposure System (Glas-Col). Single-cell suspensions of early mid-log phase bacteria were prepared in PBS with 0.05% Tween 80, and then resuspended in PBS. When indicated, doxycycline containing food (2,000 p.p.m., Research Diets) was given to mice starting at the indicated time-points to induce protein depletion. Lungs and spleen were homogenized in PBS and plated on 7H10 plates or, when necessary, in solid modified Sauton’s minimal medium to determine CFU/organ at the indicated time points.

Marmoset Infection

Common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) breeding and all procedures were performed in accordance with the recommendations of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The NIAID Animal Care and Use Committee approved the experiments described herein (Protocol LCIM-9, Permit issued to NIH as A-4149-01). Prior to infection, marmosets were transferred to a BSL-3 animal facility approved for the containment of Mtb and handled as previously described27,28. Marmosets were aged between 2 and 5 years, of both genders, and ranged in weight from ~300 to 500 g at infection with Mtb strain CDC1551 with a nose-only aerosol generated in a BANG nebulizer through a CH Technologies inhalation system (Westwood, NJ). The dose was 10–25 CFU per animal. Infection progress was monitored by PET/CT, scanned twice prior to starting the treatment and every 2 weeks during 8 weeks of treatment. Mtb exposure in this experiment resulted in an average of 10 lesions/marmoset (SD = 4) as assessed by PET/CT at 5–6 weeks and 5 marmosets among 15 individuals were randomly assigned receive ND-10885. At necropsy, samples of all PET/CT identified lung lesions, pulmonary lymph nodes, and other possibly involved organs were weighed, homogenized, and plated in triplicate onto M7H11 agar supplemented with albumin, oleic acid, dextrose, cycloheximide (0.03 μg/mL), carbenicillin (0.05 μg/mL), polymixin B (25 μg/mL), trimethoprim (20 μg/mL), and activated charcoal powder (0.4% w/v) to enumerate bacterial CFU/structure.

Plasma pharmacokinetics, dose finding, and drug treatment in marmosets

The marmoset dose of ND-10885 was optimized in order to achieve a ratio of Area Under the Curve to MIC (AUC/MIC) well above the AUC/MIC at which maximum efficacy was observed in a murine model of Mycobacterium avium infection29. This corresponded to an AUC of 50 µg h/mL. In marmosets, ND-10885 appears to undergo CYP-mediated metabolism (Supplementary Fig. 9) and solubility limited bioavailability. To increase exposure while alleviating the need for higher dosing, we co-administered 1-aminobenzotriazole (ABT, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) at 20 mg/kg31.

ND-10885 was formulated as an aqueous suspension stepwise in 10% w/v 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin, 10% w/v lecithin, 15% w/v saccharine, and 3% v/v Grape flavoring (Paddock Laboratories, Minneapolis, MN) and was administered at 1 mL/kg as an oral suspension for 2 months (50 mean dose days) to fed, hand-caught, awake, and restrained marmosets as previously described28. Doses used in pharmacokinetic and tolerability experiments included 20 mg/kg and 40 mg/kg with or without 20 mg/kg ABT administered both the previous day and 30 min prior to ND-10885. Discolored urine suggesting possible myoglobinuria was observed near the termination of the 20-dose tolerability study at 20 mg/kg, thus lower doses were used during the efficacy study. We employed a therapeutic drug monitoring approach during treatment to allow for dose escalation if the target AUC of 50 µg h/mL was not achieved. Treatment commenced with 20 mg/kg ABT 1 day prior and continued daily 30 min prior to the ND-10885 dose. Two marmosets began treatment with once daily 5 mg/kg ND-10885 and were escalated to 12.5 mg/kg daily (BI61 and M269). BI31 began daily 5 mg/kg ND-10885, was escalated to 12.5 mg/kg daily, and finally to 12.5 mg/kg twice daily in order to achieve an average AUC of 50 µg h/mL. Two marmosets were treated with the maximum dose of 12.5 mg/kg twice daily (BL24 and BI73). At the time of necropsy, tissues and lung lesions were sampled and processed for quantitation of ND-10885 as previously described27,28,53.

PET/CT data analysis

PET/CT files were co-registered and serial scans were aligned in MIM Maestro (v. 6.2, MIM Software Inc, Cleveland, Ohio), and each lesion was individually defined within a three-dimensional region of interest (ROI) on each serial scan. The numerical output of these ROIs including the radiodense volumes (−100 to 200 HU) from the CT images and [18F]-2-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (FDG) uptake (expressed as TGA) for the ROI voxels with a standardized uptake value (SUV) ≥ 2 were assessed for change in subsequent scans28. Three readers performed the extractions independently for each set of animal lesions and the data presented are an average of the resulting readings. The CFU data for each lesion or structure were aligned to the PET/CT and histology data to using the prepared necropsy maps and logs to evaluate the response of the individual lesion types during treatment.

Quantitation of ND-10885 in plasma and TB lesions

ND-10885 levels in plasma, tissues, and lung lesions were measured by LC-MS/MS in electrospray positive-ionization mode (ESI+) on a Sciex Qtrap 4000 triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer combined with an Agilent 1260 HPLC using Analyst software. Chromatography was performed with an Agilent Zorbax SB-C8 column (2.1 × 30 mm; 3.5-µm particle size) using a reverse phase gradient elution. In all, 0.1% formic acid in Milli-Q deionized water was used for the aqueous mobile phase and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (ACN) for the organic mobile phase. Multiple-reaction monitoring (MRM) of parent/daughter transitions in electrospray positive-ionization mode (ESI+) was used to quantify ND-10885. DMSO stock of ND-10885 was serial diluted in blank K2EDTA plasma (Bioreclammation) to create standard curves and quality control samples. ND-10885 was extracted by combining 20 µL of spiked plasma or study samples and 200 µL of acetonitrile/methanol 50/50 protein precipitation solvent containing 20 ng/mL Verapamil internal standard (IS). Extracts were vortexed for 5 min and centrifuged at 4000 RPM for 5 min. The supernatants were analyzed by LC-MS. Verapamil IS was sourced from Sigma-Aldrich. The following MRM transitions were used for ND-10885 (322.1/133) and Verapamil (455.4/165.2). Sample analysis was accepted if the concentrations of the quality control samples were within 20% of the nominal concentration.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Generation of graphics and data analyses were performed in Prism version 7.0 software (GraphPad), Spotfire version 7.8.0 software (TIBCO), and MIM Encore (Version 6.7.8, MIM Software Inc.).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Natalia Betancourt, Shuang Song, and Toshiko Odaira for help with mutant construction, Claire Healy for help with mutant characterization, Becky Sloan, Daniel Schimel, and Ashley Majewski for their technical expertize, Garrett C. Moraski and Marvin J. Miller for providing ND-10885, and Richard Herbert DVM for supervision of the NIAID marmoset experiments. We acknowledge James M. Bean from MSKCC and the use of the Integrated Genomics Operation Core at MSKCC, funded by the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG, P30 CA08748), Cycle for Survival and the Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Center for Molecular Oncology. This work was supported by the Tri-Institutional TB Research Unit (NIH grant U19AI111143), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s TB Drug Accelerator Program (grants OPP1024065 (D.S.), OPP1024021 (C.E.B. through the Foundation of the NIH), OPP1174780 (V.D.)), and the intramural research program of the NIAID, NIH (C.E.B.). T.B. was supported by a Potts Memorial Foundation fellowship.

Author contributions

T.B., K.O.B., D.T., C.A.E., S.W., L.E.V., D.M.W., M.L.S., E.K.D., M.Z., and B.P. performed experiments. T.M. helped to provide ND-10885. P.V.D., and T.M. analyzed metabolite data for ND-10885. J.A., H.J.Y., L.E.V., and C.E.B. analyzed the radiology and pathology data. T.B., L.E.V., H.I.B., V.D., S.E., C.E.B., and D.S. wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

The authors confirm that all relevant data are included in the paper and/or its supplement. Sequencing data can be accessed in NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under the BioProject ID PRJNA532433. Plasmids and strains generated in this study will be available through material transfer agreements upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interests: TM and PVD are employees of Eli Lilly and Company.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Gregory Cook, Deepak Kaushal and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Tiago Beites, Kathryn O’Brien.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-12956-2.

References

- 1.Mahajan R. Bedaquiline: First FDA-approved tuberculosis drug in 40 years. Int J. Appl Basic Med. Res. 2013;3:1–2. doi: 10.4103/2229-516X.112228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hards K, et al. Bactericidal mode of action of bedaquiline. J. Antimicrobial Chemother. 2015;70:2028–2037. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook, G. M., Hards, K., Vilcheze, C., Hartman, T. & Berney, M. Energetics of respiration and oxidative phosphorylation in mycobacteria. Microbiol. Spectr. 2, 10.1128/microbiolspec.MGM2-0015-2013 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Rao SP, Alonso S, Rand L, Dick T, Pethe K. The protonmotive force is required for maintaining ATP homeostasis and viability of hypoxic, nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:11945–11950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711697105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffin JE, et al. High-resolution phenotypic profiling defines genes essential for mycobacterial growth and cholesterol catabolism. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002251. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang YJ, et al. Tryptophan biosynthesis protects mycobacteria from CD4 T-cell-mediated killing. Cell. 2013;155:1296–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeJesus, M. A. et al. Comprehensive essentiality analysis of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome via saturating transposon mutagenesis. MBio8, 10.1128/mBio.02133-16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Vilcheze C, Weinrick B, Leung LW, Jacobs WR., Jr. Plasticity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis NADH dehydrogenases and their role in virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:1599–1604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1721545115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abrahams KA, et al. Identification of novel imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine inhibitors targeting M. tuberculosis QcrB. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pethe K, et al. Discovery of Q203, a potent clinical candidate for the treatment of tuberculosis. Nat. Med. 2013;19:1157–1160. doi: 10.1038/nm.3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arora K, et al. Respiratory flexibility in response to inhibition of cytochrome C oxidase in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:6962–6965. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03486-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foo, C. S. et al. Arylvinylpiperazine amides, a new class of potent inhibitors targeting QcrB of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. mBio9, 10.1128/mBio.01276-18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Weinstein EA, et al. Inhibitors of type II NADH:menaquinone oxidoreductase represent a class of antitubercular drugs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:4548–4553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500469102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yano T, et al. Reduction of clofazimine by mycobacterial type 2 NADH:quinone oxidoreductase: a pathway for the generation of bactericidal levels of reactive oxygen species. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:10276–10287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.200501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shirude PS, et al. Quinolinyl pyrimidines: potent inhibitors of NDH-2 as a novel class of anti-TB agents. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;3:736–740. doi: 10.1021/ml300134b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harbut MB, et al. Small molecules targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis type II NADH dehydrogenase exhibit antimycobacterial activity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2018;57:3478–3482. doi: 10.1002/anie.201800260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murugesan D, et al. 2-Mercapto-quinazolinones as inhibitors of type II NADH dehydrogenase and mycobacterium tuberculosis: structure-activity relationships, mechanism of action and absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion characterization. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018;4:954–969. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heikal A, et al. Activation of type II NADH dehydrogenase by quinolinequinones mediates antitubercular cell death. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016;71:2840–2847. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vilcheze C, et al. Enhanced respiration prevents drug tolerance and drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:4495–4500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704376114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsoso LG, et al. Function of the cytochrome bc1-aa3 branch of the respiratory network in mycobacteria and network adaptation occurring in response to its disruption. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:6300–6308. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.18.6300-6308.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalia NP, et al. Exploiting the synthetic lethality between terminal respiratory oxidases to kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis and clear host infection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:7426–7431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706139114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamprecht DA, et al. Turning the respiratory flexibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis against itself. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12393. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boshoff HI, Barry CE., 3rd Tuberculosis - metabolism and respiration in the absence of growth. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;3:70–80. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi L, et al. Changes in energy metabolism of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mouse lung and under in vitro conditions affecting aerobic respiration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15629–15634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507850102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu X, et al. Pyrazolo[1,5- a]pyridine Inhibitor of the respiratory cytochrome bcc complex for the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis. ACS Infect. Dis. 2019;5:239–249. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prosser G, et al. The bacillary and macrophage response to hypoxia in tuberculosis and the consequences for T cell antigen recognition. Microbes Infect. 2017;19:177–192. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Via LE, et al. Differential virulence and disease progression following Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex infection of the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) Infect. Immun. 2013;81:2909–2919. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00632-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Via LE, et al. A sterilizing tuberculosis treatment regimen is associated with faster clearance of bacteria in cavitary lesions in marmosets. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015;59:4181–4189. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00115-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moraski GC, et al. Imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine-3-carboxamides are active antimicrobial agents against mycobacterium avium infection in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016;60:5018–5022. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00618-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stringer RA, et al. 1-Aminobenzotriazole modulates oral drug pharmacokinetics through cytochrome P450 inhibition and delay of gastric emptying in rats. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2014;42:1117–1124. doi: 10.1124/dmd.113.056408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balani SK, et al. Effective dosing regimen of 1-aminobenzotriazole for inhibition of antipyrine clearance in rats, dogs, and monkeys. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2002;30:1059–1062. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.10.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sears HJ, et al. Identification of an assimilatory nitrate reductase in mutants of Paracoccus denitrificans GB17 deficient in nitrate respiration. Arch. Microbiol. 1997;167:61–66. doi: 10.1007/s002030050417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richardson DJ, Berks BC, Russell DA, Spiro S, Taylor CJ. Functional, biochemical and genetic diversity of prokaryotic nitrate reductases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2001;58:165–178. doi: 10.1007/PL00000845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Titov DV, et al. Complementation of mitochondrial electron transport chain by manipulation of the NAD+/NADH ratio. Science. 2016;352:231–235. doi: 10.1126/science.aad4017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moosa, A. et al. Susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cytochrome bd oxidase mutants to compounds targeting the terminal respiratory oxidase, cytochrome c. 61, 10.1128/aac.01338-17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Via LE, et al. Infection dynamics and response to chemotherapy in a rabbit model of tuberculosis using [(1)(8)F]2-fluoro-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography and computed tomography. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:4391–4402. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00531-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Via LE, et al. Tuberculous granulomas are hypoxic in guinea pigs, rabbits, and nonhuman primates. Infect. Immun. 2008;76:2333–2340. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01515-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benator D, et al. Rifapentine and isoniazid once a week versus rifampicin and isoniazid twice a week for treatment of drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV-negative patients: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2002;360:528–534. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09742-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Keijzer J, et al. Thioridazine alters the cell-envelope permeability of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Proteome Res. 2016;15:1776–1786. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b01037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ratnakar P, Murthy PS. Trifluoperazine inhibits the incorporation of labelled precursors into lipids, proteins and DNA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1993;110:291–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scherr N, et al. Targeting the Mycobacterium ulcerans cytochrome bc1:aa3 for the treatment of Buruli ulcer. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:5370. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07804-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schnappinger D, O’Brien KM, Ehrt S. Construction of conditional knockdown mutants in mycobacteria. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015;1285:151–175. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2450-9_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schnappinger D, et al. Transcriptional adaptation of mycobacterium tuberculosis within macrophages: insights into the phagosomal environment. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:693–704. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pashley CA, Parish T. Efficient switching of mycobacteriophage L5-based integrating plasmids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003;229:211–215. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00823-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim JH, et al. A genetic strategy to identify targets for the development of drugs that prevent bacterial persistence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:19095–19100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315860110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murphy KC, Papavinasasundaram K, Sassetti CM. Mycobacterial recombineering. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015;1285:177–199. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2450-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li H, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DePristo MA, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robinson JT, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:24. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thorvaldsdottir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief. Bioinform. 2013;14:178–192. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Wenger AM, Zehir A, Mesirov JP. Variant review with the integrative genomics viewer. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e31–e34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zimmerman, M. et al. Ethambutol partitioning in tuberculous pulmonary lesions explains its clinical efficacy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.61, 10.1128/AAC.00924-17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all relevant data are included in the paper and/or its supplement. Sequencing data can be accessed in NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under the BioProject ID PRJNA532433. Plasmids and strains generated in this study will be available through material transfer agreements upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.