Abstract

Introduction

In real-life practice, asthma remains poorly controlled, with a considerable burden on patients’ quality of life. Budesonide/formoterol (B/F) Easyhaler® has demonstrated similar dose consistency, therapeutic equivalence, and equivalent bronchodilator efficacy to B/F Turbuhaler®, but no real-life comparisons are yet available in patients switching from B/F Turbuhaler® to B/F Easyhaler®.

Methods

The primary objective of this real-life, non-interventional, observational study was to show non-inferiority of asthma control when adult patients in Swedish primary care with persistent asthma switched from B/F Turbuhaler® to B/F Easyhaler®. At visit 1, baseline demographic and endpoint data were recorded, and eligible patients switched to B/F Easyhaler®. The study comprised a control visit (visit 2) and a concluding examination (visit 3) after 12 weeks. Asthma control was assessed using the Asthma Control Test (ACT). The mini-Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) and lung function test were performed, and participants and investigators answered questionnaires about ease-of-use and teaching.

Results

A total of 117 patients were enrolled in the on-treatment population; 81 (64.8%) were female. At visit 3, B/F Easyhaler® demonstrated non-inferiority to B/F Turbuhaler®; the mean difference in change from baseline ACT was statistically significant (18.9 vs. 20.7, respectively; p < 0.0001) and met the non-inferiority criteria of B/F Easyhaler® being greater than − 1.5 points versus the reference product. Asthma was well controlled in 62 (53.0%) patients at baseline, increasing to 83 patients (70.9%) at visit 3. Patients experienced statistically significant improvements in mini-AQLQ score after B/F Easyhaler® treatment and lung function remained stable across the treatment period. B/F Easyhaler® was easy to learn and prepare for use.

Conclusion

This real-life, non-interventional, non-inferiority study in adults with persist asthma demonstrates equivalent or better disease control when patients switch from B/F Turbuhaler® to B/F Easyhaler®. A further study with direct comparison between treatments could add to the understanding of inhaler switch.

Funding

Orion Corporation, Orion Pharma.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12325-019-00940-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Asthma, Asthma control, Inhaler technique, Inhaler preference, Inhaler switch, Budesonide/formoterol Turbuhaler®, Budesonide/formoterol Easyhaler®

Introduction

Asthma is a common, chronic respiratory disease that is characterized by chronic inflammation of the airways and associated with airway hyperresponsiveness. It is reported by the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) as a highly prevalent health problem affecting 1–16% of the population in different countries globally [1]. During the late twentieth century, even after acknowledging increased disease awareness and diagnosis, the prevalence and morbidity of asthma increased in many parts of the world [2, 3]. In a 2009 study in West Sweden the prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma was estimated to be 8.3%, making it one of the most common diseases in Sweden [4].

Although clinical research suggests that asthma control is achievable, asthma remains poorly controlled in real-life clinical practice and continues to be a public health concern in many countries [5, 6]. Indeed, despite the availability of established treatment guidelines [1], many patients with asthma still experience persistent symptoms from poorly controlled disease [7, 8], often characterized by asthma exacerbations [9]. In Sweden, patients with frequent asthma exacerbations are characterized by greater age, are typically female, and experience a high prevalence of comorbidities; recent findings from Janson et al. suggest that improvements are needed in the Swedish healthcare system in order to improve management of asthma in these patient subgroups [10]. Overall, the clinical reality is that asthma is poorly controlled for a significant proportion of patients with consequent lifestyle limitations, psychological and social effects, and a considerable burden on patient’s quality of life [9, 11, 12].

Inhalation is recommended as the primary route of administration for medication used to manage asthma [11]. However, the effectiveness of inhaled medication can be influenced by factors such as age, gender, education, inhalation technique, type of inhaler used, and many other factors [13, 14]. It is well documented that adopting a suboptimal inhalation technique may have clinical implications for treatment efficacy and subsequent disease control [15].

Bufomix Easyhaler® (Orion Pharma, Espoo, Finland) is a multidose dry powder inhaler (DPI) approved in several European countries for the administration of budesonide and formoterol in combination for the treatment of adults and adolescents (12–17 years of age) with asthma [16, 17]; a mild-strength formulation (80/4.5 μg) is also approved for use in children at least 6 years of age in Sweden [18]. Combination therapy of budesonide (an inhaled corticosteroid) and formoterol fumarate (a long-acting β2-adrenergic agonist) (B/F) has demonstrated an additive effect in alleviating asthma symptoms [19]. B/F Easyhaler® has demonstrated similar dose consistency compared with Symbicort Turbuhaler® (AstraZeneca, Cambridge, UK) at clinically relevant air flow rates [20]. This study used flow air rates collected from patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) by Malmberg et al., who reported similar in vitro flow rate dependency compared with Turbuhaler® [21]. Therapeutic equivalence and equivalent bronchodilator efficacy have also been reported between the two inhalers in pharmacokinetic and in vitro/in vivo correlation modeling studies [22], and equivalent bronchodilator efficacy was also demonstrated in a randomized, single-dose, four-period crossover study [23]. The real-life clinical effectiveness of B/F Easyhaler® in the treatment of asthma in adult outpatients in routine daily clinical practice was also confirmed in non-randomized, open-label, single-arm studies conducted in Poland and Hungary [24, 25]. However, there are no studies available that stratified by prior treatment and therefore no real-life comparisons are available in a patient population that has switched from B/F Turbuhaler® to B/F Easyhaler®.

Existing data suggest that patients with asthma and physicians in Swedish general practice are reluctant to switch to another DPI [26]; Ekberg-Jansson et al. reported that switching inhaler, especially without a primary healthcare visit, was associated with decreased asthma control resulting in a higher exacerbation rate and more outpatient hospital visits, compared with no switch. The results of randomized controlled trials may not predict the value of switching patients to a different inhaler in real-life clinical practice, where inhaler technique and device characteristics can influence effectiveness [27]. In addition, patient- and physician-perceived satisfaction with the inhaler is an important factor driving treatment compliance and outcomes. Consequently, there is a need for real-life studies in patients with asthma that examine how different inhaler devices compare in terms of ease of use, time required for education, acceptance, and patient or physician preferences.

The present real-life study was conducted in seven primary healthcare centers in Sweden. It aimed to evaluate whether asthma control is maintained (i.e., non-inferior) after a switch from B/F Turbuhaler® to B/F Easyhaler®.

Methods

Study Participants

Patients with persistent asthma were included in this multicenter, non-interventional, single-arm, prospective observational study conducted in Sweden. Adult patients literate in Swedish, who had been previously diagnosed with asthma (according to therapeutic guidelines), and who had been using B/F Turbuhaler® regularly for at least 6 months were eligible for enrolment. Patients were excluded from the study if they were participating in any other trial, had hypersensitivity to any ingredient in the inhaler product, or if they were pregnant or breastfeeding. Patients with instable asthma (defined as more than three oral steroids regimes during last year or hospitalization due to asthma during the last 6 months) were also excluded. Furthermore, patients with known pollen allergy were excluded from participating during the pollen season in Sweden.

Patients were recruited upon confirmation that the study site was planning to follow local recommendation lists stating that B/F Easyhaler® was recommended. At this point, patients were asked if they were willing to participate in the study and switch from B/F Turbuhaler® to B/F Easyhaler®.

Procedures and Study Medications

This open real-life, prospective study was conducted across seven primary healthcare centers in the middle and south of Sweden, with assessments conducted during patients’ visits to their doctor or asthma nurse. It was a non-interventional, single-arm observational study conducted between 21 December 2015 and 9 December 2017.

The primary objective was to show non-inferiority of asthma control when switching from B/F Turbuhaler® 160/4.5 μg or 320/9.0 μg inhalation to B/F Easyhaler® 160/4.5 or 320/9.0 μg/inhalation. Secondary objectives were to show that the switch from B/F Turbuhaler® to B/F Easyhaler® could be achieved without worsening of asthma-related quality of life or a deterioration of lung function (as measured by spirometry). A further objective was to examine whether there were any differences in perceptions of ease of use of the two devices and assessment of training requirements for B/F Easyhaler® use.

The study was performed in accordance with European regulations for non-interventional, observational studies, and the International Council on Harmonisation, Good Clinical Practice standards, and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee of Stockholm before its start. Before inclusion, all patients provided written informed consent.

Study Design

All eligible patients were using B/F Turbuhaler® for at least 6 months at the beginning of the study (visit 1). Participants switched from B/F Turbuhaler® to B/F Easyhaler® (Orion Pharma, Finland) 160/4.5 μg or 320/9 μg/inhalation device metered DPI. During the study each patient used his/her asthma medication at the same dose as before the study, as described by the doctor.

The timing of visits and assessment schedule are shown in Table 1. At visit 1, the recruiting physicians recorded demographic data and smoking status. The study nurse/physician educated the participants how to handle the inhaler device according to the summary of product characteristics. At the same visit, spirometry, asthma control, and asthma-related quality of life (QoL) assessments were also performed. The study comprised two further visits; after approximately 2 weeks, the asthma nurse checked patients’ device handling and inhalation technique following the switch to B/F Easyhaler®. During a concluding examination conducted after 12 ± 2 weeks, the doctor or asthma nurse evaluated the change from baseline for all endpoints and assessments. All measurements were evaluated as change from baseline (visit 1) to visit 3. Documentation was recorded by the investigating physician or nurse using standardized, numbered case report forms.

Table 1.

Timing of visits and schedule of assessments

| Assessment | Visit 1 (baseline) Pre-switch/study start |

Visit 2 (control visit) Week 2 (+ 1 week) |

Visit 3 (end of study) Week 12 (+ 2 weeks)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informed consent | X | ||

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria | X | ||

| Demography | X | ||

| Concomitant medication | X | ||

| Smoking status | X | ||

| Patient questionnaire | Xb | Xc | Xc |

| Patient assessment of device handling and inhalation technique | Xb | Xc | Xc |

| Physician/nurse assessment of teaching and inhaler use | Xc | Xc | Xc |

| Asthma control test | Xb | Xc | |

| Mini-AQLQ | Xb | Xc | |

| Spirometry | Xb | Xc | |

| Adverse events | Xc | Xc |

AQLQ Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire, B/F budesonide and formoterol fumarate

aOr early withdrawal from study

bAssessment of B/F Turbuhaler®

cAssessment of B/F Easyhaler®

Primary Endpoint

The primary endpoint was non-inferiority of asthma control after switching from B/F Turbuhaler® to B/F Easyhaler®. Asthma control was assessed during visits 1 and 3 using the Asthma Control Test (ACT; QualityMetric, Lincoln, RI, USA) [28]. The ACT is a self-assessment questionnaire of five items investigating asthma control in terms of activity limitation, shortness of breath, night symptoms, use of rescue medication, and the subjective perception of the level of asthma control. A minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of 3 has been established [29]. Asthma control was categorized according to GINA 2018 guidelines as very poorly controlled (ACT ≤ 15), not well controlled (ACT 16–19), and well controlled (ACT > 20) [1].

Secondary Endpoints

Secondary endpoints were asthma-related quality of life, lung function, and perception/preference of the inhaler(s) among both patients and investigators.

Asthma-Related Quality of Life

Change in asthma-related quality of life was assessed using the mini-Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (mini-AQLQ) [30], which was completed by the patient. This instrument has 15 questions in the same domains as the original AQLQ (symptoms, activities, emotions, and environment) and takes 3–4 min to complete. The mini-AQLQ has very good reliability, cross-sectional validity, responsiveness, and longitudinal validity. Higher ratings denote less impairment (better quality of life) and an overall mini-AQLQ score below 4 indicates a very limited daily life due to asthma; the MCID is a mean change in score of greater than 0.5.

Lung Function Tests

Spirometry was performed according to routine clinical practice in Sweden, including pre-bronchodilator assessment [31], following the guidelines for standardization produced by the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society [32]. Forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) data were collected. Lung function was also expressed as FEV1% predicted normal and FVC% predicted normal.

Learning and Usage Questionnaire

To evaluate the ease of learning and usage of B/F Turbuhaler® and B/F Easyhaler® in everyday life, patients received a questionnaire [33] comprising closed questions scored on a six-point scale (1–6, very easy to unsatisfactory, respectively) to assess patients’ assessment of inhaler use and the complexity of the instructions for use. This self-assessment questionnaire (Supplementary Table 1) was completed during all visits and related to experiences with either B/F Turbuhaler® (visit 1) or B/F Easyhaler® (visits 2 and 3). The investigating physician or nurse also assessed the ease of teaching B/F Easyhaler® use (visit 1) and the success of the patient in learning to how use it (visits 2 and 3).

Safety

Adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs were assessed and documented in the case report form from enrolment (at the time informed consent was signed) until the patient left the study or the end-of-study visit. The investigator was required to document whether a reasonable causal relationship with the drug (yes/no) could be assigned for each adverse reaction reported.

Statistical Analyses

Sample Size

It was estimated that a sample size of 155 evaluable patients was required to provide an approximate statistical power of 90% at a significance level of 0.05 for the two-sided noninferiority test (accounting for an expected 15% dropout rate). The proposed sample size was based on assumptions that the ACT would worsen by at most 0.5 points after switching. The assumed standard deviation of the ACT was 3.5 and there was an assumed 0.5-point correlation between baseline and the last visit in ACT.

Analysis of Primary and Secondary Endpoints

All analyses were performed in the on-treatment population, which comprised of those who enrolled and completed visit 3. Data were reported descriptively using mean and standard deviation values, minimum and maximum quartiles as percentages, or means with 95% confidence intervals.

The null hypothesis was that switching from Turbuhaler® to Easyhaler® worsens ACT and the alternative hypothesis is that switching from Turbuhaler® to Easyhaler® does not worsen ACT clinically significantly, i.e., non-inferiority. For the primary endpoint, non-inferiority was met when the mean change from baseline in ACT over the 12-week treatment period was greater than − 1.5 points (< 50% of the MCID) [29]. A mixed linear model was used to compare change from baseline ACT; a p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Analysis of mini-AQLQ was similar to that used for the primary variable. Change from baseline for spirometry values was tested for statistical difference and the results will be reported with estimated means and 95% confidence intervals. These assessments were also analyzed using a mixed linear model.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS for Windows version 9.4.

Results

Patient Socio-Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

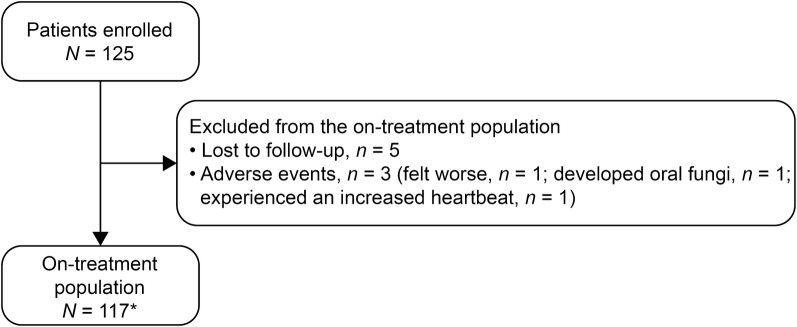

Overall, 125 patients were enrolled in the study, of whom five were lost to follow-up and three withdrew following an adverse event. Consequently, 117 completed visit 3 and formed the on-treatment group; this group included three patients whose visit 3 occurred less than 12 weeks after visit 1 (Fig. 1). The age and sex distribution of enrolled in the study is shown in Table 2. The mean age of the enrolled patients was 53.4±16.5 years. The majority of patients were female (n = 81; 64.8%) and were educated to high school level or above (n = 112; 89.6%). Only five of the enrolled patients (4.3%) were active smokers. The mean ACT score was 19.0 ± 3.9; at baseline, 58 (46.4%) of the 125 participants had poorly controlled asthma (ACT score < 20).

Fig. 1.

Patient disposition. *Includes three patients whose visit 3 occurred less than 12 weeks after visit 1

Table 2.

Socio-demographic and baseline characteristics for the enrolled population (n = 125)

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 53.4 (16.5) |

| Sex (female), n (%) | 81 (64.8) |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) | 171.8 (9.9) |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 81.3 (16.4) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Primary school | 13 (10.4) |

| High school | 54 (43.2) |

| University or college degree | 58 (46.4) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |

| Current smoker | 5 (4.3) |

| Former smokera | 40 (34.8) |

| Never smokeda | 70 (60.9) |

| HRQoL, mean (SD) mini-AQLQ | 5.4 (1.0) |

| Asthma control | |

| ACT score, mean (SD) | 19.0 (3.9) |

| Lung function, mean (SD)b | |

| FEV1 (L) | 2.7 (0.8) |

| FEV1% predicted | 85.2 (13.6) |

| FVC | 3.6 (1.1) |

ACT Asthma Control Test, AQLQ Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, FVC forced vital capacity, HRQoL health-related quality of life, SD standard deviation

aData from n = 110 presented

bData from n = 124 presented

Primary Endpoint: Non-Inferiority of B/F Easyhaler® Compared with B/F Turbuhaler®

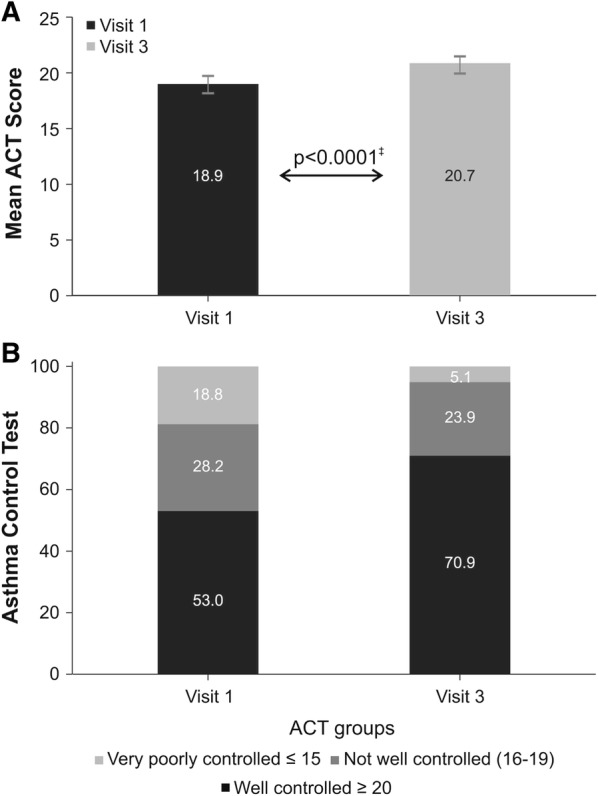

The mean treatment difference in change from baseline ACT (1.8 points) over the 12-week treatment period was more than 50% of the MCID (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table 2) with a statistically significantly higher value for B/F Easyhaler® compared with the reference product, B/F Turbuhaler® (18.9 vs. 20.7, respectively; p < 0.0001). Thus, B/F Easyhaler® met the non-inferiority criteria of having an ACT score which was greater than − 1.5 points versus the reference product. Overall, asthma was well controlled in 62 (53.0%) of the 117 patients in the on-treatment group at baseline, and the number with well-controlled asthma increased to 83 patients (70.9%) at visit 3, an increase between visit 1 (baseline) and visit 3 of 17.9% (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Mean ACT scores* (a) and ACT asthma control categories† reported (b) at baseline (visit 1) and visit 3 (on-treatment population; n = 117). *Data are presented as mean (95% CI); †Categories defined according to 2018 GINA guidelines (1); ‡P value refers to mixed linear model of change from baseline (visit 1) to visit 3 (week 12 of treatment). Treatment with B/F Turbuhaler® and B/F Easyhaler® evaluated at visit 1 and 3, respectively. ACT Asthma Control Test, ANOVA analysis of variance, GINA Global Initiative for Asthma, B/F budesonide and formoterol fumarate

Secondary Endpoints

Change in QoL Assessed by Mini-AQLQ

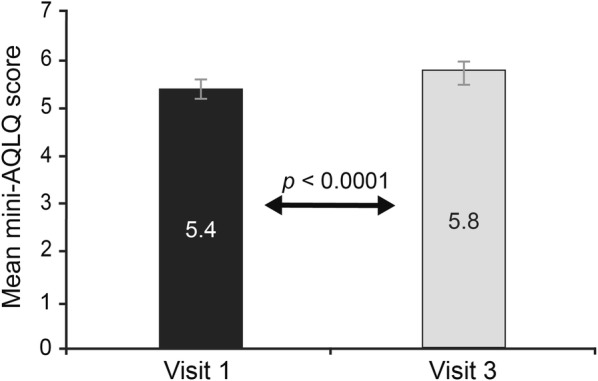

When compared to baseline, patients experienced a statistically significant improvement in mini-AQLQ score after 12 weeks of B/F Easyhaler® treatment. Of the 117 patients in the on-treatment group, 54 patients (46.2%) were experiencing little to no limitation due to their asthma (mini-AQLQ ≥ 6) at visit 3, compared with 39 (33.3%) at baseline. The mean change in mini-AQLQ score between baseline and visit 3 was 0.4 (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Assessment of fixed-dose budesonide/formoterol fumarate combination therapy on changes in asthma-related QoL in patients with asthma (on-treatment population; n = 117). Data are presented as mean (95% CI). P value refers to mixed linear model of change from baseline (visit 1) to visit 3 (week 12 of treatment). Treatment with B/F Turbuhaler® and B/F Easyhaler® evaluated at visit 1 and 3, respectively. ANOVA analysis of variance, AQLQ Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire, B/F budesonide and formoterol fumarate, QoL quality of life

Spirometry

Lung function parameters remained stable across the treatment period. FEV1, FVC, and all percentage predicted values were similar from visit 1 through visit 3; all differences were non-significant (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Evaluation of lung function in patients with asthma following 12 weeks’ treatment with B/F Easyhaler® (on-treatment population; n = 117). Data are presented as mean (95% CI). P values refer to mixed linear model of change from baseline (visit 1) to visit 3 (week 12 of treatment). Treatment with B/F Turbuhaler® and B/F Easyhaler® evaluated at visit 1 and 3, respectively. B/F budesonide and formoterol fumarate, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, FVC forced vital capacity

Physician/Nurse and Patient Perspectives of B/F Easyhaler® Use

On the basis of the data from the physician and patient questionnaires, B/F Easyhaler® appears to be easy to learn and to prepare ahead of use. At visit 3, having used the B/F Easyhaler® for 12 weeks, 80.2% of patients responded that they had found it easy to learn how to use the B/F Easyhaler® (Fig. 5a). Likewise, when questioned at visit 3, 80.2% of patients reported that it was easy to prepare B/F Easyhaler® for use; at visit 1 fewer patients (70.1%) had felt that the B/F Turbuhaler® was easy to prepare for use (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Evaluation of patient perspectives on ease of learning to use (a) and ease of preparation of the inhaler (b) (on-treatment population; n = 117). Patients assessed ease of learning different aspects of B/F Turbuhaler® (visit 1) and B/F Easyhaler® (visits 2 and 3) use in everyday life using a questionnaire, answering closed questions scored on a six-point scale, 1 (very easy)–6 (unsatisfactory) [33]. B/F budesonide and formoterol fumarate

The physician/nurse investigator perspectives on the B/F Easyhaler® appear to confirm the patients’ experiences. At visit 1, the majority of patients (n = 95; 81.9%) required less than 5 min to learn how to use B/F Easyhaler® and only 22 patients (19.0%) needed to repeat the training session (Table 3). By visit 3, the investigators considered 111 patients (96.5%) able to use B/F Easyhaler® without any difficulty. Furthermore, they considered integration of B/F Easyhaler® to be good to very good by 105 patients (91.3%). Almost three-quarters of patients were reported by the investigators to have good or very good compliance with B/F Easyhaler® use (Table 3).

Table 3.

Physician and nurses’ perspectives on how easy it is to teach and learn B/F Easyhaler® use? (on-treatment population; n = 117)

| Physician/nurse perspectives of B/F Easyhaler® | Number of responses (%) |

|---|---|

| Visit 1 | |

| Was it easy for patients to learn how to use B/F Easyhaler®?a | |

| Very easy | 83 (71.6) |

| Quite easy | 30 (25.9) |

| Medium easy | 3 (2.6) |

| How much time did patients need to learn how to use B/F Easyhaler®?a | |

| < 5 min | 95 (81.9) |

| 5–10 min | 21 (18.1) |

| Was it necessary to repeat the learning exercise?a | |

| No | 94 (81.9) |

| Yes | 22 (19.0) |

| If yes, how many times was the learning exercise repeated?b | |

| No need | 92 (82.9) |

| Once | 17 (15.3) |

| Two times or more | 2 (1.8) |

| Visit 3 | |

| How good is the integration of the inhaler use in the patient’s everyday life?c | |

| Very good | 53 (46.1) |

| Good | 52 (45.2) |

| Moderate | 9 (7.8) |

| Bad | 1 (0.9) |

| In my opinion the patient has difficulty in handling the inhaler?c | |

| No | 111 (96.5) |

| Yes | 4 (3.5) |

| How would you assess patient compliance?d | |

| Very good | 54 (47.4) |

| Good | 30 (26.3) |

| Moderate | 26 (22.8) |

| Bad | 4 (3.5) |

Percentages were calculated from the number of responses received; some of these numbers include observed cases prior to patients being included in the on-treatment population

B/F budesonide and formoterol fumarate

an = 124

bn = 119

cn = 115

dn = 114

Safety

Three adverse events were reported in the study by patients who had switched to B/F Easyhaler® and led to treatment discontinuation; these included “felt worse,” developed oral fungi, and increased heart rate.

Discussion

This real-life, non-interventional, single-arm study in patients who switched from B/F Turbuhaler® to B/F Easyhaler® demonstrated that B/F Easyhaler® is non-inferior to B/F Turbuhaler® in patients with asthma. Our results demonstrated that most patients treated with B/F Easyhaler® for 12 weeks obtained good or complete asthma control (ACT score 20–25 points). The mean ACT score for B/F Turbuhaler® at study initiation indicated that asthma that was not well controlled (ACT < 20). Following a switch to B/F Easyhaler®, a statistically significant improvement in mean ACT and a numerical difference in the total proportion of patients reporting well-controlled asthma were observed. Furthermore, patients experienced statistically significant improvements in mini-AQLQ score and lung function remained stable across the 12-week treatment period. It should be noted that the improvements in ACT and mini-AQLQ scores did not reach clinical significance.

Whilst these findings relating to the reference product are positive, they should be interpreted with some notes of caution. The study had some limitations. Conclusions on the effectiveness of B/F Easyhaler® are limited by the lack of exacerbation data and several caveats relate to the conduct of the study. Firstly, data on patient adherence with B/F Turbuhaler® were unavailable and the reasons for switching from B/F Turbuhaler® were unknown. Also, inclusion in clinical or real-life studies may increase patients’ adherence to treatment or lead to better compliance with instructions from their doctor. A study setting with direct concurrent comparison between inhaler treatments could overcome many of these limitations; however, this study was designed to mimic the real-life treatment practices with as limited interference as possible.

The strength of the study lies in its “real-life” design and the inclusion of a representative sample of patients in Sweden, using B/F Turbuhaler® and B/F Easyhaler® in everyday clinical practice. With regards to the sample size, although this was below target, the sample size did not impact the power since the assumption in the power calculations was that ACT would worsen; in fact, the ACT improved after switching and therefore the power of the study was higher than originally calculated.

Our study provides useful insight into learning inhaler technique and subsequent inhaler use. Inhaler technique is a practical issue that impacts making an informed decision. Additionally, a patient’s ability to obtain, process, and understand basic health information (health literacy) is an important consideration in making appropriate health decisions [1]. Consequently, the choice of inhaler should be made in consultation between the physician and the patient and be in accordance with patient’s needs, situation, and preference followed by sufficient training [1, 34]. The present study that included training on the correct use of Easyhaler® inhaler device with subsequent beneficial results is in line with these reports. Certainly, switching inhaler without a face-to-face consultation and appropriate training is inadvisable and has been shown to be associated with poor asthma control [26, 35]. Swedish patients with asthma who switched inhaler without a primary healthcare visit demonstrated decreased asthma control resulting in higher exacerbation rates and more outpatient hospital visits [26]. In view of this it is important that physicians, nurses, and patients are confident that the selected inhaler is easy to use.

In our study, more patients regarded B/F Easyhaler® as “easy” for all aspects of everyday use assessed, compared with B/F Turbuhaler®. Furthermore, study physicians reported that B/F Easyhaler® was easy to teach with their patients learning inhaler use quickly. This is in accordance with a report of the results of two real-life studies with Easyhaler® for daily inhalations of other medications in patients with asthma or COPD. In those studies most investigators found Easyhaler® easy to teach, and second or third instructions were necessary in only 26% of the patients. The patients reported that it was easy to learn how to use Easyhaler® and they were satisfied or very satisfied with the use of the inhaler [36]. Although not comparative, our data appears to confirm the results of previous patient preference studies comparing the inhalers for the delivery of other asthma medications [37]. These two studies have demonstrated better patient acceptability for Easyhaler® compared with Turbuhaler® and an overall preference for the Easyhaler®. Longer-term studies would be required to confirm whether these user characteristics might translate into improved patient adherence and long-term asthma control.

Conclusion

In this real-world, 12-week, multicenter, non-interventional, non-inferiority study in patients with stable asthma who switched from B/F Turbuhaler® to B/F Easyhaler®, the non-inferiority criteria were met for B/F Easyhaler® by showing a mean improvement of asthma control and asthma quality of life, measured by ACT and mini-AQLQ.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the investigators and patients at the following sites where the study was conducted: Astma/Allergis/Lung mottagningen, Lidingö Sjukhus; Vårdcentralen Hemse; Vårdcentralen Ronneby; Vårdcentralen Kallinge; Näsets Läkargrupp Höllviken; Vårdcentralen Nyhälsan, Bräcke Diakoni, Nässjö; Vårdcentralen Visby Norra.

Funding

The study design, collection, analyses and interpretation of the data, writing and article processing charges and the Open Access fee were sponsored by Orion Corporation, Orion Pharma. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by David Griffiths, PhD, of Bioscript Medical, funded by Orion Corporation, Orion Pharma.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published, responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosures

Paula Rytilä is a full-time employee of Orion Corporation, Orion Pharma. Mikael Sörberg is a full-time employee of Orion Corporation, Orion Pharma. Mikko Vahteristo is a full-time employee of Orion Corporation, Orion Pharma. Jörgen Syk reports personal fees received from Orion Corporation, Orion Pharma, during the conduct of the study. Ines Vinge has nothing to declare.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Footnotes

The original version of this article was revised as the mean difference in change from baseline ACT was incorrectly reported in the abstract.

Enhanced digital features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.7867940.

Change history

6/9/2019

Unfortunately, the mean difference in change from baseline ACT was incorrectly reported in the abstract as 19.0 vs. 20.8 instead of <Emphasis Type="Bold">18.9 vs. 20.7</Emphasis>

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA), National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. GINA report: Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Available at https://ginasthma.org/2018-gina-report-global-strategy-for-asthma-management-and-prevention/. Accessed 1 Jan 2019.

- 2.Woolcock AJ. Worldwide trends in asthma morbidity and mortality. Explanation of trends. Bull Int Union Tuberc Lung Dis. 1991;66(2–3):85–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burr ML. Is asthma increasing? J Epidemiol Community Health. 1987;41(3):185–189. doi: 10.1136/jech.41.3.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lotvall J, Ekerljung L, Ronmark EP, et al. West Sweden Asthma Study: prevalence trends over the last 18 years argues no recent increase in asthma. Respir Res. 2009;10:94. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slejko JF, Ghushchyan VH, Sucher B, et al. Asthma control in the United States, 2008–2010: indicators of poor asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(6):1579–1587. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Price D, Fletcher M, van der Molen T. Asthma control and management in 8,000 European patients: the REcognise Asthma and LInk to Symptoms and Experience (REALISE) survey. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24:14009. doi: 10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stallberg B, Lisspers K, Hasselgren M, Janson C, Johansson G, Svardsudd K. Asthma control in primary care in Sweden: a comparison between 2001 and 2005. Prim Care Respir J. 2009;18(4):279–286. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2009.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lisspers K, Stallberg B, Hasselgren M, Johansson G, Svardsudd K. Quality of life and measures of asthma control in primary health care. J Asthma. 2007;44(9):747–751. doi: 10.1080/02770900701645298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peters SP, Ferguson G, Deniz Y, Reisner C. Uncontrolled asthma: a review of the prevalence, disease burden and options for treatment. Respir Med. 2006;100(7):1139–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janson C, Lisspers K, Stallberg B, et al. Prevalence, characteristics and management of frequently exacerbating asthma patients: an observational study in Sweden (PACEHR) Eur Respir J. 2018;52(2):1701927. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01927-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Global Asthma Network. The Global Asthma Report 2014. Available at https://www.globalasthmareport.org/resources/Global_Asthma_Report_2014.pdf. Accessed 1 Jan 2019.

- 12.Pavord ID, Mathieson N, Scowcroft A, Pedersini R, Isherwood G, Price D. The impact of poor asthma control among asthma patients treated with inhaled corticosteroids plus long-acting beta2-agonists in the United Kingdom: a cross-sectional analysis. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27(1):17. doi: 10.1038/s41533-017-0014-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lavorini F, Magnan A, Dubus JC, et al. Effect of incorrect use of dry powder inhalers on management of patients with asthma and COPD. Respir Med. 2008;102(4):593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melani AS, Bonavia M, Cilenti V, et al. Inhaler mishandling remains common in real life and is associated with reduced disease control. Respir Med. 2011;105(6):930–938. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selroos O, Pietinalho A, Riska H. Delivery devices for inhaled asthma medication. Clinical implications of differences in effectiveness. BioDrugs. 1996;6:273–99. [Google Scholar]

- 16.European Medicines Compendium. Orion Pharma (UK) Limited. Summary of Product Characteristics for Fobumix Easyhaler 160/4.5 inhalation powder. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/8706/smpc/ Accessed 25 Jul 2018.

- 17.European Medicines Compendium. Orion Pharma (UK) Limited. Summary of product characteristics for Fobumix Easyhaler 320 micrograms/9 micrograms, inhalation powder. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/8438/smpc/ Accessed 25 Jul 2018.

- 18.Medical Products Agency. Summary Public Assessment Report for Bufomix Easyhaler in Sweden. Available at https://docetp.mpa.se/LMF/Bufomix%20Easyhaler%2080%20microgram_4.5%20microgram%20per%20inhalation%20inhalation%20powder%20ENG%20sPAR_09001be6810d4a5e.pdf/. Accessed 4 Sep 2018.

- 19.Zetterström O, Buhl R, Mellem H. Improved asthma control with budesonide/formoterol in a single inhaler compared with budesonide alone. Eur Respir J. 2001;18(2):262–268. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00065801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haikarainen J, Selroos O, Löytänä T, Metsärinne S, Happonen A, Rytilä P. Budesonide/formoterol Easyhaler®: performance under simulated real-life conditions. Pulm Ther. 2017;3(1):125–138. doi: 10.1007/s41030-016-0025-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malmberg LP, Everard ML, Haikarainen J, Lahelma S. Evaluation of in vitro and in vivo flow rate dependency of budesonide/formoterol Easyhaler®. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2014;27(5):329–340. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2013.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lahelma S, Sairanen U, Haikarainen J, et al. Equivalent lung dose and systemic exposure of budesonide/formoterol combination via Easyhaler and Turbuhaler. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2015;28(6):462–473. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2014.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lahelma S, Vahteristo M, Metev H, et al. Equivalent bronchodilation with budesonide/formoterol combination via Easyhaler and Turbuhaler in patients with asthma. Respir Med. 2016;120:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pirożyński M, Hantulik P, Almgren-Rachtan A, Chudek J. Evaluation of the efficiency of single-inhaler combination therapy with budesonide/formoterol fumarate in patients with bronchial asthma in daily clinical practice. Adv Ther. 2017;34(12):2648–2660. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0641-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamasi L, Szilasi M, Galffy G. Clinical effectiveness of budesonide/formoterol fumarate Easyhaler® for patients with poorly controlled obstructive airway disease: a real-world study of patient-reported outcomes. Adv Ther. 2018;35(8):1140–1152. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0753-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ekberg-Jansson A, Svenningsson I, Ragdell P, et al. Budesonide inhaler device switch patterns in an asthma population in Swedish clinical practice (ASSURE) Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69(10):1171–1178. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Virchow JC, Crompton GK, Dal Negro R, et al. Importance of inhaler devices in the management of airway disease. Respir Med. 2008;102(1):10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas M, Kay S, Pike J, et al. The Asthma Control Test (ACT) as a predictor of GINA guideline-defined asthma control: analysis of a multinational cross-sectional survey. Prim Care Respir J. 2009;18(1):41–49. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2009.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schatz M, Kosinski M, Yarlas AS, Hanlon J, Watson ME, Jhingran P. The minimally important difference of the Asthma Control Test. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(4):719–723e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Cox FM, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Development and validation of the Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire. Eur Respir J. 1999;14(1):32–38. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14a08.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hedenstrom H, Malmberg P, Fridriksson HV. Reference values for lung function tests in men: regression equations with smoking variables. Ups J Med Sci. 1986;91(3):299–310. doi: 10.3109/03009738609178670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller MR, Crapo R, Hankinson J, et al. General considerations for lung function testing. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(1):153–161. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hantulik P, Wittig K, Henschel Y, Ochse J, Vahteristo M, Rytila P. Usage and usability of one dry powder inhaler compared to other inhalers at therapy start: an open, non-interventional observational study in Poland and Germany. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2015;83(5):365–377. doi: 10.5603/PiAP.2015.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horne R, Price D, Cleland J, et al. Can asthma control be improved by understanding the patient's perspective? BMC Pulm Med. 2007;7(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas M, Price D, Chrystyn H, Lloyd A, Williams AE, von Ziegenweidt J. Inhaled corticosteroids for asthma: impact of practice level device switching on asthma control. BMC Pulm Med. 2009;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galffy G, Mezei G, Nemeth G, et al. Inhaler competence and patient satisfaction with Easyhaler®: results of two real-life multicentre studies in asthma and COPD. Drugs R D. 2013;13(3):215–222. doi: 10.1007/s40268-013-0027-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schweisfurth H, Malinen A, Koskela T, Toivanen P, Ranki-Pesonen M, German Study Group Comparison of two budesonide powder inhalers, Easyhaler and Turbuhaler, in steroid-naive asthmatic patients. Respir Med. 2002;96(8):599–606. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2002.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.