Abstract

Introduction and Goal:

Stroke is a serious health condition that disproportionally affects African-Americans relative to non-Hispanic whites. In the absence of clearly defined reasons for racial disparities in stroke recovery and subsequent stroke outcomes, a critical first step in mitigating poor stroke outcomes is to explore potential barriers and facilitators of poststroke recovery in African-American adults with stroke. The purpose of this study was to qualitatively explore poststroke recovery across the care continuum from the perspective of African-American adults with stroke, caregivers of African-American adults with stroke, and health care professionals with expertise in stroke care.

Materials and Methods:

This qualitative descriptive study included in-depth key informant interviews with health care providers (n = 10) and focus groups with persons with stroke (n = 20 persons) and their family members or caregivers (n = 19 persons). Data were analyzed using thematic analysis according to the Social Ecological Model, using both inductive and deductive approaches.

Findings:

Persons with stroke and their caregivers identified social support, resources, and knowledge as the most salient factors associated with stroke recovery. Perceived barriers to recovery included: (1) physical and cognitive deficits, mood; (2) medication issues; (3) lack of support and resources; (4) stigma, culture, and faith. Health care providers identified knowledge/information, care coordination, and resources in the community as key to facilitating stroke recovery outcomes.

Conclusions:

Key findings from this study can be incorporated into interventions designed to improve poststroke recovery outcomes and potentially reduce the current racial-ethnic disparity gap.

Keywords: Stroke, recovery, caregivers, outcomes, Focus groups, disparities

Introduction

Stroke is a serious health condition that disproportionally affects African-Americans relative to non-Hispanic whites (whites).1 For example, African-Americans have twice the risk of stroke as compared to their white counterparts.1–3 Additionally, African-Americans are more likely to: (1) have a stroke at a younger age2–4; (2) experience a more severe stroke5–7; (3) die from a stroke8; (4) and have more poststroke disability.9–11 There is additional concern about stroke in African-Americans because although the rate of stroke is declining in the United States, the reduced stroke rates are not observed in African-Americans.4

The specific underlying causes of racial-ethnic disparities in stroke incidence and stroke-related outcomes are not entirely clear. Considerable concerns exist regarding racial-ethnic disparities in stroke recovery patterns that contribute to negative long-term outcomes in this high-risk population. According to Skolarus & Burke (2015), greater poststroke disability among African-Americans relative to whites may be due to differences in recovery occurring in 2 distinct recovery periods that occur after initial hospitalization (early recovery and community living).12 Therefore, as adults with stroke return to their communities, many have plateaued in their recovery and have persisting poststroke deficits. Consequently, they are attempting to reintegrate into their prestroke communities but with new poststroke deficits. It is tenable then that African-Americans not only return to their communities with new poststroke deficits but they also have less improvement during this early recovery period. Therefore, they are attempting reintegration into their communities during the community living period at a much lower baseline level of function.12 An alternative hypothesis is that African-Americans simply have greater decline during the community living period.12 Therefore, African-Americans may be experiencing the hypothesized decline over a longer time frame because they typically experience their strokes at a younger age.2–4 Regardless, a better understanding of the racial-ethnic differences in stroke recovery trajectories and subsequently poststroke outcomes is required.

A second key factor believed to contribute to racial disparities in stroke as well as other chronic health conditions is the impact of structural racism. Structural racism occurs when institutions and their ideologies and processes of care converge to create inequities in health-related outcomes in racial-ethnic minority groups.13 Racism in itself exists throughout the life course and is connected with other systems of inequity.14 The impact of structural racism on health outcomes is not simply determined by the functioning of healthcare systems, but also reflects inequities in society housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, and other factors that contribute to inequities that traditionally exist among racial and ethnic minorities.15

More importantly, structural racism is not easy to quantify because it is grounded in not only the interconnections of institutions that provide healthcare but also in the context of historical inequities in healthcare systems, healthcare practices and the aforementioned societal factors.15 Yet what is clear, is that structural racism creates a level of risk for racial-ethnic minorities that is undermining the health of minority populations.16

In the absence of clearly defined reasons for racial disparities in stroke recovery and subsequent stroke outcomes, a critical first step in mitigating poor stroke outcomes is to explore potential barriers and facilitators of poststroke recovery in African-American adults with stroke. Studies of barriers and facilitators related to stroke outcomes have been previously explored and have emphasized: stroke recovery and prevention17; adherence to secondary stroke prevention18; rehabilitation goal setting19; and community care of persons with stroke.20 Yet we are only aware of 1 study that was designed to specifically address issues with African-American adults with stroke. Unfortunately, this study was limited to African-American men under the age of 65 only17 and has limited transferability.

Although African-American adults with stroke face poor stroke recovery outcomes when compared to whites, little published research exists that describes supports and obstacles among this population. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to describe poststroke recovery across the care continuum from the perspective of African-American adults with stroke, caregivers of African-American adults with stroke, and health care professionals with expertise in stroke care. The rationale for this study was to identify barriers and facilitators to perceived recovery and to use the information to develop culturally-tailored interventions for African-American adults with stroke living in the community. We hypothesized that using this multi-perspective approach (patient, caregiver, community, provider, health-care system) would help to identify the most salient factors critical to optimal stroke recovery in this high-risk population and may alleviate some of the disparities occurring among African Americans with stroke through future interventional efforts.

The study reported here is part of the Wide Spectrum Investigation of Stroke Outcome Disparities on Multiple Levels (WISSDOM) Center, a larger study of racial disparities in stroke recovery.21 WISSDOM was developed to bring together a multidisciplinary team of scientists to examine disparities in stroke recovery focused on 3 interrelated approaches: basic science, clinical science, and population science projects.

Materials and Methods

Design

A qualitative descriptive study design was used for this research, which included in-depth key informant interviews and focus groups. Qualitative descriptive design is an interpretive approach that is useful for summarizing events and phenomena as they are perceived and described.22 All data were obtained from interviews and focus groups which were determined to be the most appropriate approach to elicit information from the 3 respective groups of interest (adults with stroke, family members/caregivers, and expert panel including healthcare providers, community providers, and community advocates).

Setting and Sample

A purposive sample from the Charleston County, SC area and 3 neighboring counties (Dorchester, Berkeley, and Georgetown) was recruited as part of the WISSDOM-CINGS protocol to obtain a representation of: (1) African-American adults with stroke; (2) family members and caregivers; and (3) professionals that work with adults with stroke in either a health care or community context. Participants were excluded if they could not communicate in English language. We conducted a series of focus groups which were held in conference rooms at multiple community-based sites in the Charleston, SC area. These focus groups were conducted in various locations around the Charleston area to improve access from areas that are rural and to encourage participation among potential participants who may have had difficulty accessing the medical university area. The key informant interviews were held at the offices of healthcare professionals at 3 systems in the Charleston, SC area.

Procedures

This study was reviewed and approved by the Medical University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board.

If participants agreed to take part in this formative qualitative study, they were contacted by study personnel and scheduled for an interview or focus group. Participants were provided a copy of the consent form for their review prior to engaging in this qualitative research. Following a discussion related to informed consent, questions were answered, and all signed an informed consent to participate in the research project (focus groups or key informant interviews).

Data Collection

We collected interview and focus group data during Fall and Winter, 2015–2016. Focus groups were conducted with adults with stroke (n = 20 persons) and family members and/or caregivers (n = 19 persons). Focus groups were conducted among: (1) adults with stroke only; (2) caregivers and family members only; and (3) jointly with both adults with stroke and family members/caregivers to explore both individual and shared views. Key informant interviews were conducted with the expert panel health professionals (n = 10). A series of questions designed by the research team (all experienced in stroke care) were used to guide the discussion. Focus groups and interviews used the same guiding questions that focused on perceived barriers and facilitators to stroke recovery, expectations for recovery, and potential targets or strategies to maximize stroke recovery in African-Americans. Sample questions included: “What are the barriers or things that interfere or get in the way of and facilitators or things that help African-Americans with stroke recovery?” and “What are the recommended actions to maximize stroke recovery and quality in African-American stroke patients?” Participants were also asked questions about the impact of families and healthcare professionals beliefs and attitudes about stroke recovery. Similarly, all participants were asked about the influences of the healthcare systems where they received care or about availability to healthcare in the communities where African-Americans with stroke lived after hospitalization. Investigators asked probing follow-up questions as indicated to encourage clarification and elaboration.

We audio-recorded the discussions and maintained field notes, which detailed observations and context. The face-to-face, semistructured interviews lasted approximately 30–45 minutes and focus groups lasted approximately 1.5 hours each. Prior to the focus group, all participants completed a questionnaire to elicit information about their sociodemographic characteristics and the stroke survivors and caregivers were administered a self efficacy scale. The stroke caregivers were also administered a caregiver burden scale.

Data Analysis

Audio-recordings from interviews and focus groups were professionally transcribed verbatim. Initial hand coding was completed by 2 investigators (C.J., S.Q.) using a first level approach which focuses on identify distinct concepts and categories.23 Codes were reviewed and con-firmed by (G.S.M., C.E.). Transcripts were then uploaded to NVivo 11.4.2 (QSR International, Pty, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia), which was followed by second level, line-by-line coding of text by an experienced qualitative researcher (M.N.). Data were analyzed using thematic content analysis according to the Social Ecological Model, using both inductive and deductive approaches. A detailed audit trail of decisions during data analysis was maintained, which included reflective notes, emergent codes, and sequence of primary and secondary coding.24 Analyzed data were compared across investigators and reviewed during multiple sessions by qualitative methodologists (M.N. and C.J.) and the primary investigator (G.S. M.) for confirmability and trustworthiness of data.25,26

Results

Characteristics of study participants

Participants in the focus groups were primarily African-American (97.4%), female (74.4%), and greater than 60 years of age (60.5%). A majority of the participants had income less than $35,000 annually (n = 18). Additionally, participants’ years of education ranged from less than high school to graduate school. The stroke survivors specifically were primarily female, retired, over the age of 60, and had experienced their stroke more than 1 year prior to the focus groups and had at least a high school education. The sample collectively experienced a range of disabilities ad less than half were able to walk inside or outside their homes, exercise or do things like they were able to do before their stroke. See Table 1 for a profile of the stroke survivors.

Table 1.

Characteristics of stroke survivor focus group participants

| Characteristic | N = 20 |

|---|---|

| Time Poststroke | |

| <1 y | 10% |

| >1 y | 90% |

| Female | 75% |

| Age | |

| 40–49 | 5% |

| 50–59 | 30% |

| 60+ | 65% |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 10% |

| High school diploma or GED | 30% |

| Some college but no degree | 35% |

| College | 25% |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 5% |

| Retired | 55% |

| Disabled-not able to work | 30% |

| Not employed/not looking for work | 10% |

| Stroke self efficacy (select items) | Confident you are able to do the task |

| Able to get self out of bed | 60% |

| Walk about the inside home | 45% |

| Walk safely outside the home | 40% |

| Dress and undress | 50% |

| Prepare a meal | 50% |

| Do own exercise each day | 25% |

| Continue to do most things like before stroke | 25% |

Abbreviations: GED, General Education Diploma

The expert panel included 10 healthcare and community providers with expertise in stroke care for individual interviews. The 10-member expert panel consisted of a chaplain, psychologist, pharmacist, nurse, physical therapist, vocational rehabilitation specialist, physician assistant, and 3 physicians with specialization in internal medicine, family medicine, or neurology.

Barriers and Facilitators of Stroke Recovery – Reports from Persons with Stroke, Caregivers, and Health Care Providers

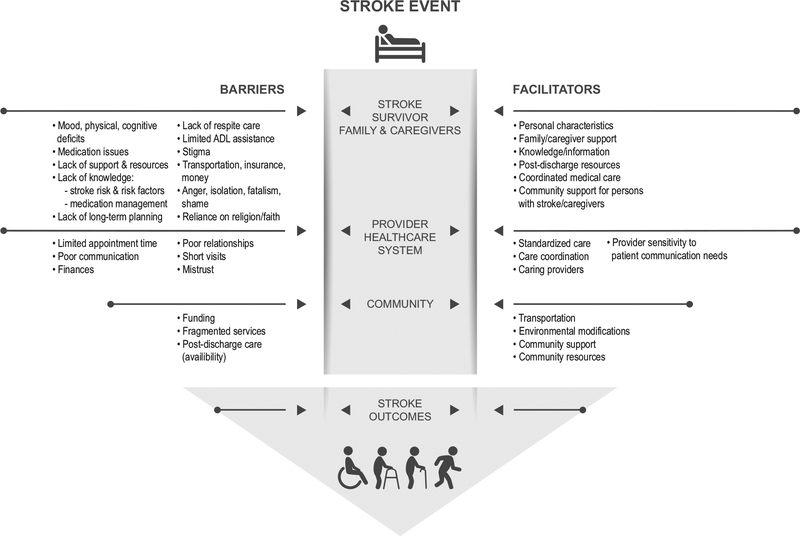

Focus groups for persons with stroke and family members/caregivers were organized for participants to provide information related to barriers and facilitators of stroke recovery associated with: (1) the person with stroke, (2) the family member/caregiver, (3) the community, and (4) the healthcare system and providers where persons with stroke received care. A range of themes were identified related to barriers and facilitators to stroke recovery by adults with stroke and caregivers/family members. Fig. 1 is highlights the barriers and facilitators at different levels (stroke survivor, family/caregiver, community, provider/healthcare system).

Figure 1.

Perspectives of barriers and facilitators.

Adults with stroke:

Barriers – Adults with stroke identified several perceived barriers to recovery including: (1) physical and cognitive deficits, mood (2) medication issues, (3) lack of support and resources, (4) stigma and culture/faith. First, persons with stroke reported that poststroke depression and an inability to perform everyday tasks due to residual physical and cognitive impairment was a major barrier. The complexity of depression was noted to be intermittent as well as a consequence of the stroke recovery experience. For example, adults with stroke reported that “depression comes in” during the recovery process. Similarly, some reported that depression resulted from other factors experienced across the care continuum including lack of resources such as insurance, misdiagnoses, or difficulty being diagnosed, and were also attributed to common poststroke medications. Depression related concerns were also related to “being a burden on the family.” In fact, many participants reported a concern about burdening their family members. Alongside depression were issues with emotion and attitudes. For example, participants reported being “angry,” “stubborn,” “being [in] denial,” and some reported an “expectation for full recovery to prestroke stage” and felt depressed when this was not always the case. For example, 1 women who had a stroke during the past year stated, “[I] haven’t driven yet. It’s driving me out of my mind because [my husband] doesn’t allow me to drive. He takes me everywhere.”

Depression was a barrier that compounded poststroke physical and cognitive impairment. Participants with stroke reported needing to “learn how to do everything over again” 1 particpant, shared “I learned I can’t button my shirt all the way and I’m a minister and I get dressed, I just take the tie. Won’t be buttoned, but none of them would know, but I can’t button my dress shirt over my pants shared” and yet another gentleman shared “For me I think that the hardest thing is to unbutton my shirt-sleeve. It take a long time for me to learn.” Communication issues were present as indicated by the participants with stroke who noted “[my] speech is not what it used to be” or “[I] can’t stand a lot of noise” and had “inability to do prestroke activities” reflective of the implications of physical and cognitive/communication disability after stroke.

Medication issues also emerged as a barrier to stroke recovery. Difficulty accessing medications due to “lack money or insurance for medications” or concerns about taking too many medications or “on 22 meds, too many meds” are concerns for adults with stroke. Clearly some seem to deviate from medication recommendations as indicated by “not taken since daughter went online and found side effects” or making the decision that “meds don’t work” without understanding the impact of the decision while other voiced concern about cost and “lack of insurance for meds.”

A third key issue was related to lack of social support and limited resources. Participants noted that social support was “less and less as days go by” and there are “little outside programs that too many people don’t hear about.” Similarly, participants indicated substantial concern with the lack of resources such as being “put in a position where I had no choice but to find means” or “lack of at-home services; no one to change a light bulb.” It was also noted that there were no or minimal resources for persons with stroke in rural communities.

Stigma and culture/faith issues emerged as a perceived barrier of stroke recovery among adults with stroke. One adult with stroke reported concern with being labeled a “stroke victim” and the “stigma or label being put on a person.” This issue seemed of particular concern for a male stroke survivor who noted “[a] man is supposed to show strength and here I’m the weak one.” Culture/faith was a noted barrier to accessing care as “African-Americans go to God first, wait for a response, hence delay in seeking care.” Delays in seeking treatment were in combination with a reduced focus on preventive care. Examples were shared by a stroke survivor who said “85 percent of African-American men don’t go to doctors” or another who noted “Blacks don’t necessarily go to doctors as quickly and as often as whites do.”

Adults with Stroke:

Facilitators – Identified facilitators included: (1) personal characteristics; (2) family/caregiver support; (3) knowledge/information; and (4) postdischarge resources. Reported personal characteristics deemed key to poststroke recovery included: self-motivation, patience, and faith. Self-motivation was believed to “put (me) in a position where I had no choice but to find means” or that the adult with stroke “researched and [was] motivated to find resources and programs.” Another participant highlighted the importance of patience. He “learned that I had to have patience with myself and I use myself as a best friend to myself.” Along with patience, faith was voiced as critical to the recovery process. Participants noted “I’m gonna walk with Jesus,” “God brought me through,” and “we know that God can take us through anything if we trust in him.” Faith in God and the bible were articulated as critical to the recovery process.

Family/caregiver support was another noted facilitator for the recovery process. Participants acknowledge being “fortunate to have supporting caregivers” whereas another noted “her husband brought me through.” Care-givers were noted critical to providing postdischarge care. Knowledge/information emerged as a facilitator to stroke recovery. Participants noted needing information about medication and diet that was not provided at discharge. Others expressed beliefs that they could have benefitted from additional information about comorbidities and stroke prevention. Along with postdischarge information, a range of postdischarged services were noted as critical to the recovery process including: (1) respite care; (2) rehab, physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy; (3) follow-up care and care coordination; (4) family/caregiver support; (5) knowledge/information; and (6) postdischarge resources.

Family/Caregivers:

Barriers – Key identified barriers included (1) lack of support and resources; (2) lack of knowledge about stroke; and (3) culture/faith. All key barriers to stroke recovery reported by family members/ caregivers overlapped with barriers reported by persons with stroke. Family members/caregivers noted that social support was “less and less help as days go by” or they experienced “lack of support after discharge.” There was also concern regarding “programs for stroke victims/family are not disseminated.” Similarly, stroke knowledge-related issues were identified by persons with stroke and family members/caregivers. One family member/care-giver noted “lot of people wouldn’t even know the symptoms of stroke” or have knowledge about “risk factors for stroke and stroke recurrence.” Other knowledge related problems centered around “misconception about stroke,” “medication management,” and limited knowledge among African-Americans that may be related to a “tendency not to ask questions.” The final barrier reported was associated with culture/faith. Similar to the adults with stroke, time to seeking treatment seemed related to cultural beliefs and faith as indicated by “culturally in black families, they’re not going to react as quickly to things all the time as Caucasians.” Cultural differences in alternative medicine also emerged as indicated by “take home remedies in the first place instead of going to the doc (doctor).”

Family/Caregiver:

Facilitators – Key identified facilitators included: (1) emotional support/patience; (2) resources/support; and (3) knowledge/information. Very similar to responses of persons with stroke, family member/caregivers also noted a need for patience and need to serve as a cheerleader to the person with stroke. A daughter of a stroke survivor, when discussing the need for patience, shared “you have to be a good listener…because with [the] slur talking, sometimes you don’t understand what they are saying. A couple of times you hear them and then again and again, over and over, you don’t hear.” One caregiver reported “I’ve taken on the role of cheerleader and tell him you’re getting better, don’t worry about it.” Personal characteristics of compassion, love, caring, and encouragement were described as critical to stroke recovery. Caregivers believed resources for care-givers were critical including “support groups for care-givers to share and learn” and that it didn’t matter if support groups were face to face or not in person. Support groups offered an opportunity to receive knowledge/ information for many of the participants. However, 1 family member was empowered to locate information and resources on his own and said, “do you[r] own research to figure out like how it works.”

Community/Environment:

Barriers – Reported community and environmental barriers primarily centered upon support. Issues emphasized poor postdischarge care and social support. One person with stroke reported, “once you come out the hospital, society doesn’t know,” whereas others noted a “lack of programs available.” One senior family noted a particularly distressing account of poor social support when she reported “can’t find nobody to even change a light bulb.” Environmental barriers also included access to public and private buildings in the community. One participant described challenges with accessibility as noted by “a lot of things, buildings, you can’t get into them if you have a stroke.”

Community/Environment:

Facilitators – Family members and caregivers also discussed facilitators to stroke recovery existing in the context of the community. Community-based social supports and resources emerged to promote perceived recovery. A particpant whose sister had a stroke emphasized “If they had a support group to help people and have like things to show people how long it will take to get certain strengths back and stuff like that, that will help the people to understand.” Several participants mentioned the church community and described the supportive nature of other members. Persons with stroke and their families were encouraged to “thank church members” and “be there for them.” It was also noted that supports included both “your peers” and “your environment.”

Provider/Healthcare System:

Barriers – Reported barriers associated with providers and healthcare systems were related to: (1) limited time for patients and families; (2) mistrust of healthcare systems; (3) poor communication; and (4) limited stroke-related information provided by providers. Persons with stroke noted “being rushed, half the doctors have no more than 15 minutes,” that “staff have no time to listen,” “do not pay attention,” and “doctors don’t have time to check medication compatibility.” The reports aligned with mistrust of healthcare systems due to “misdiagnoses and lack of attention for 12 hours thinking [they were] drunk” and “ambulance people didn’t know I had a stroke.” Others noted “hospitals are not backing you” and “doctors give you some stuff (medications) that really don’t help. You get the same symptom over and over again.” Similarly, persons with stroke voiced concern over poor communication and labeled it as “one of the biggest hindrances.” Limited information provided by healthcare systems was voiced as an additional concern. Persons with stroke noted “info[rmation] about how [stroke] can change your life was not necessarily given” and “they need to give more information to everybody as far as the caregiver and the patient.”

Provider/Healthcare System:

Facilitators – Persons with stroke identified a need for caring providers to facilitate positive poststroke recovery processes. They reported needing “quick attention by doctors and quick referral to therapists and appreciated providers who listen and spend time with the patient/family.”

Strategies to Improve Stroke Recovery – Reports From an Expert Panel

The expert panel identified key areas they believed negatively impacted stroke recovery (barriers) and those critical to improving stroke recovery (facilitators). Key themes emerged were related to: (1) the stroke survivor; (2) family/caregiver; (3) community/environment; and (4) what providers and healthcare systems might do better to improve stroke recovery. Refer to Fig. 1 for a visual depiction on perceived barriers and facilitators among the expert panel.

Persons with stroke:

Barriers – The expert panel reported that adults with stroke who lack knowledge about stroke risk, stroke risk factors, and medication management contributed negatively to stroke recovery outcomes. Regarding medication management specifically participants noted: (1) lack of resources to purchase medications; (2) medications not being filled or picked up; (3) medications not being taken; and (4) not willing to accept how they made the person with stroke feel. Other barriers were related to resources: limited transportation for follow-up visits, inability to purchase quality foods, and loss of work and insurance. Finally, providers noted that negative attitudes and beliefs were detrimental to the recovery process. Specific examples included: (1) being angry and not willing to adapt; (2) giving up and isolating themselves; (3) fatalism; waiting to die; (4) feeling ashamed about aspects of the disability; (5) dependence of religion; and (6) premorbid attitudes. Facilitators – In contrast, the expert panel reported that established prestroke medical relationships, coordinated medical care, and availability of postdischarge services were critical for poststroke recovery. Postdischarge services that were primarily emphasized focused on poststroke rehabilitation and coordinated postacute care services.

Family/Caregiver:

Barriers – The expert panel reported that stroke survivor’s family/caregivers lack of long-term planning, lack resources for respite care, and their inability to assist patients with activities of daily living (ADLs) were detrimental to the recovery process. Specifically, the panel participants noted family members/caregivers often need to remain employed, although they were simultaneously needed to assist the person with post-stroke disability, which was a negative contributor to the recovery process. Other concerns included potential abuse and limited attempts to verbalize needs of the adult with stroke. Facilitators – Similar to facilitators at the individual level for persons with stroke, the expert panel primarily emphasized the need for community support, respite care, and organized care services postdischarge.

Community/Environment:

Barriers – The expert panel noted limited funding for community services, fragmented community services particularly for travel, and underestimation of the contribution of churches to patients with stroke as key contributors to negative post-stroke recovery. Facilitators – Key facilitators of stroke recovery identified by the expert panel included: availability of transportation (e.g., shared ride services) and ability to obtain needed environmental modifications such as ramps or assistive technologies as critical to post-stroke recovery outcomes.

Provider/Healthcare System:

Barriers – At the provider/healthcare system level, the expert panel identified limited time to work with stroke patients, poor patient-provider relations, and limited finances as key negative contributors to stroke recovery. Physicians, in particular consistently voiced concern with an inability to spend enough time to build relationships with patients and a poor understanding of the impact of patients’ finances on their decision-making process. “I get this cross-section of what it must be like and that’s it…how do you interpret?” “When [time] resources are limited, it’s easier to be paternalistic.” Other negative contributors to poststroke recovery included providers minimizing patients’ concerns with diminished sexual relations and intimacy or losing their patience with persons with stroke who desire faster recovery. One provider captured many of these issues when they noted “most MDs and other health professionals are taught the technical aspects of what to do and do not think about real life.” Facilitators identified by the expert panel included: (1) standardization of care; (2) care coordination; and (3) the need for providers to provide a keen ear to reports of poststroke disability. The panel suggested providers needed to be better at listening to the unique needs of persons with stroke to better understand the complexity of how their poststroke condition manifests in their everyday life. Similarly, providers discussed needing to focus on risk factor control via adherence to medications. Finally, the panel recommended providers present persons with stroke with a worst-case scenario for recovery while helping them to understand that some aspects of recovery would be an adaptation to a new reality rather than returning to their prestroke level of functioning.

Disussion

The objective of this study was to utilize a multi-perspective approach to identify the most salient perceived barriers and facilitators of stroke recovery for African-Americans. Several key findings emerged from this study that can be incorporated into interventions designed to improve poststroke recovery outcomes and reduce the current racial-ethnic disparity gap. We will discuss the findings from 2 perspectives; first perceived barriers and facilitators to stroke by persons with stroke and family members/caregivers and the second perspective on barriers and facilitators of stroke recovery from an expert panel of stroke healthcare providers.

The first key finding was that persons with stroke and caregivers identified support, resources, and knowledge as the most salient factors associated with stroke recovery. In Fig. 1, lack of social support and lack of resources critical to the stroke survivor, care-giver/family member, and community emerged as critical barriers. Similarly, resources and supports emerged as critical facilitators of stroke recovery for the person with stroke, family/caregiver, and community/environment. It is notable that knowledge about the stroke condition, stroke risk, and risk factors and recovery was identified as a barrier when not provided by providers/healthcare systems but as a facilitator to stroke recovery when available for persons with stroke, caregivers, and the community. Additionally, personal characteristics of patients, family members/caregivers, and providers were deemed a critical facilitator of poststoke recovery.

It is no surprise that social support and the availability of resources are critical factors for stroke recovery. An early study by Glass et al found that social support was associated with faster and greater recovery of functional ability after stroke and socially isolated patients were at risk for worse recovery.27 Social support is critical to stroke recovery because in its absence, patients can feel a disconnect leading to feelings of frustration, apathy, and depression, which are negative predictors of stroke recovery.28 For some persons with stroke, lack of support during the recovery period can impact their motivation to engage in rehabilitation therapies or reengagement of premorbid function tasks that are necessary to return to independence. Additionally, some people need assistance with reconnecting with their family and community as they recalibrate to their new normal that frequently includes some level of physical and cognitive disability. More importantly, socializing with individuals who were part of their prestroke lives are critical to limiting depression and other negative feelings while facilitating poststroke independence.

Intertwined with the need for support is the need for resources (personal, family, and community-based). Financial and nonfinancial resources emerged as critical to the recovery process. Financial resources are frequently needed for medication, rehabilitation services, environmental modifications, and transportation. In the absence of such resources, many persons with stroke do not have access to the necessary services critical to optimal recovery. Compounding the need for financial resources is an inability to re-engage in employment due to poststroke disability. Nonfinancial resources include community-based services such a support groups and other community-based services that are frequently free to persons with stroke but viewed as critical to the recovery process.

The final major component to poststroke recovery identified from multiple perspectives was the need for knowledge/information related to stroke. Persons with stroke and family member/ caregivers voiced significant frustration about a lack of information related to stroke, stroke risk, stroke prevention, and the location of stroke-related resources after discharge to home and their community. Although some had family histories of stroke, many noted not knowing: (1) the cause of stroke; (2) what causes stroke risk; and (3) what strategies they should use to improve their current level of function while also reducing their risk of recurrent stroke. Unfortunately, these findings highlight previous reports of poor stroke-related knowledge among individuals at risk for stroke and those who have a history of stroke.29,30 Therefore, programs designed to enhance stroke recovery outcomes should at a minimum include information about stroke and the factors that are most critical to improving the stroke recovery process. Such information should extend beyond stroke-related information (cause, risk, etc) and also include information about national and community resources that might improve their access to the necessary resources for optimal stroke recovery.

A second major finding emerged from the expert panel was that limited knowledge about stroke, fragmented care, limited time for care, and limited patient finances were critical barriers to stroke recovery. The panel also emphasized the need for organized and coordinated care, standardized care, and sensitivity to patient needs as key facilitators of stroke recovery. The expert panel, persons with stroke, and family members were all in agreement regarding the need for improved knowledge/information on stroke. From the provider perspective, understanding stroke is critical to secondary stroke prevention or to reduce the risk of stroke-related risk factors. Healthcare providers are guided by the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association “Guidelines for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients with Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack”.31 Evidence based guidelines offer recommendation for the control of stroke risk factors and guide the care of persons with stroke. However, people who do not understand stroke or stroke risks may be more likely to be noncompliant with risk reduction strategies in the absence of a clear understanding of the management approach. For example, participants in this study reported issues related to delays in seeking treatment and medication adherence issues unique to African-Americans. Therefore, cultural approaches to care and lack of knowledge about stroke has the potential to create a critical barrier to optimal patient and provider agreement and engagement in the poststroke management.

The final collection of issues expressed by the expert panel related to fragmented care, limited time for care, and the need for organized, coordinated, and standardized care are primary symptoms of the current healthcare organization approach in the United States today. Recent changes in the organization of Medicare and the establishment of accountable care organizations (ACOs) may assist stroke providers in the management of stroke patients. ACOs are groups of hospitals and physicians that agree to be jointly responsible for healthcare organization, spending, and quality of care.32, 33 Physicians and healthcare systems engaged in the care of stroke patients will receive incentives to coordinate patient care and approach patient care collectively.32 Many ACOs have already demonstrated improvements on measures of quality each year since inception in 2012.34 These changes will not completely solve the problems reported here that likely contribute to poor access to the care persons with stroke need but is a critical step to addressing the issues highlighted by the panel.

Finally, issues related to lack of sensitivity of healthcare providers to the persons with stroke perspective were acknowledged by the expert panel comprised predominately of health providers. The issues examined in this study are specifically related to a racial-ethnic minority population. These findings along with fragmented care may suggest aspects of structural racism related to interpersonal racism and bias within healthcare systems and the potential to contribute to disparate stroke outcomes.15 Healthcare systems frequently offer cultural sensitivity training to address such issues. However, little attention has been given to the outcomes of these trainings or whether such training truly impacts the beliefs and attitudes of healthcare providers about racial-ethnic minority patients. This issue is of concern given the general lack of concordance of the racial-ethnic background of the patients and healthcare providers. Consequently, evidence suggest strategies to combat structural racism can be complicated. Strategies must engage healthcare systems at the highest levels and include training for the next generation of healthcare professionals to not only recognize the problem but to develop strategies to facilitate change.15

Additionally, interventions designed to address disparities in health must also extend beyond traditional healthcare systems and must be designed to address the social, physical, economic, and political environments that impact the larger social contexts that contribute to disparities.35 Such interventions require transdisciplary teams with the requisite skills to address the multilevel contributors to disparities in outcomes for conditions such as stroke.36 In addition, a continued focus must remain on provision of culturally sensitive care that emphasizes respect for patients and their culture, and in turn enables patients to feel comfortable with the healthcare provider creates a stronger patient-provider relationship and greater trust.37 Culturally sensitive care also empowers the patient to engage during the visit to share their views and concerns.

Conclusion

In this study of African-Americans with stroke, support, resources, and knowledge were identified as critical to the recovery process. In their absence, African-Americans with stroke are more likely to experience social isolation and depression, are less likely to secure the necessary resources such as rehabilitation, and are less likely to have the necessary knowledge to understand stroke to the degree that facilitates optimal poststroke recovery and risk factor control. This study also highlighted factors healthcare providers believe are critical to poststroke recovery, such as patient understanding of stroke and stroke risk factor control, organized and coordinated care, evidenced-based stroke care, and provided sensitivity to the needs of the persons with stroke. These factors collectively should be considered in interventions designed to improve stroke recovery and long-term outcomes of African-Americans with stroke.

Financial Disclosure:

This publication was supported by the Strategically Focused Research Network Award from the American Heart Association #15SFDRN258700 #15SFDRN2480016 and was supported, in part, by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Grant Number UL1 TR001450. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix A: Perceived barriers and facilitators of stroke recovery among persons with stroke and family members/caregivers

| Barriers | Facilitators | |

|---|---|---|

| Persons with stroke | • Mood, physical, and cognitive deficits • Medication issues • Lack of support and resources • Stigma • Culture/faith |

• Interpersonal characteristics • Family/caregiver support • Knowledge/information, • Postdischarge resources |

| Family/caregivers | • Lack of support and resources • Lack of knowledge about stroke • Culture/faith |

• Emotional support/patience, • Resources/support, • Knowledge/information |

Appendix B: Expert panel perspectives of barriers and facilitators of stroke recovery

| Barriers | Facilitators | |

|---|---|---|

| Persons with stroke | • Knowledge/Information (lack of): stroke risk, risk factors, medication management • Resources for follow-up care • Transportation, insurance, money • Attitudes: anger, isolation, fatalism, shame • Reliance on religion |

• Coordinated medical care • Postdischarge services |

| Family/caregivers | • Lack of long-term planning • Lack of respite care • Limited ADL assistance |

• Community support for persons with stroke/caregivers • Organized postdischarge care |

| Community/environment | • Funding • Fragmented services |

• Transportation • Environmental modifications |

| Provider/healthcare system | • Limited appointment time • Poor relationships • Finances |

• Standardized care • Care coordination • Provider sensitivity to patient communication needs |

Appendix C: Overlapping barriers and facilitators of stroke recovery Overlapping characteristics in italics.

| Barriers | Facilitators | |

|---|---|---|

| Persons with stroke |

Support (lack of) Resources (lack of) Mood Physical/cognitive deficits Medication issues Stigma Culture/faith |

Interpersonal characteristics Family/caregiver support Knowledge/information Resources. |

| Family/caregivers |

Support (lack of) Resources (lack of) Knowledge/information (lack of) Culture/faith |

Emotional support/patience Support Resources Knowledge/information |

| Community/environment |

Support Postdischarge care (availability) |

Support (community-based) Resources (community-based) |

| Provider/healthcare system |

Knowledge/information (lack of) Short visits Mistrust Communication (poor) |

Knowledge/information Caring providers |

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2017 Update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017;135 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National stroke Association, African Americans and stroke. Available at: https://www.stroke.org/africanamericansandstroke. 2013.

- 3.White H, Boden-Albala B, Wang C, et al. Ischemic stroke subtype incidence among whites, blacks, and Hispanics: the Northern Manhattan study. Circulation 2005;111: 1327–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleindorfer DO, Khoury J, Moomaw CJ, et al. Stroke incidence is decreasing in whites but not in blacks: a population-based estimate of temporal trends in stroke incidence from the greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky stroke study. Stroke 2010;41:1326–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horner RD, Matchar DB, Divine GW, et al. Racial variations in ischemic stroke-related physical and functional impairments. Stroke 1991;22:497–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones MR, Horner RD, Edwards LJ, et al. Racial variation in initial stroke severity. Stroke 2000;31:563–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuhlemeier KV, Stiens SA. Racial disparities in severity of cerebrovascular events. Stroke 1994;25:2126–2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howard VJ. Reasons underlying racial differences in stroke incidence and mortality. Stroke 2013;44:S126–S128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGruder HF, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, differences in disability among black and white persons with stroke United States, 2000–2001. MMWR 2005;54:3–6.15647723 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellis C, Boan A, Turan TN, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in post-stroke rehabilitation utilization and functional outcomes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015;96:84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chase JD, Huang L, Russell D, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in disability outcomes among postacute home care patients. J Aging Health 2017. E-Pub ahead of print 0898264317717851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skolarus LE, Burke JF. Towards an understanding of racial differences in post-stroke disability. Curr Epidemiol Rep 2015;2:191–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequities: old issues, new directions. Du Bois Rev 2011;8:115–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gee GC, Hing AH, Mohammed S, et al. Racism and the life course: taking time seriously. Am J Public Health 2019;109:S43–S47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agenor M, et al. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet 2017;389:1453–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lukachko A, Hatsenbuehler ML, Keyes KM. Structural racism and myocardial infarction in the United States. Soc Sci Med 2014;103:42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blixen C, Perzynski A, Cage J, et al. Stroke recovery and prevention barriers among young African American men: potential avenues to reduce health disparities. Top Stroke Rehabil 2014;2:432–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jamison J, Sutton S, Mant J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to adherence to secondary stroke prevention medications after stroke: analysis of survivors and caregivers views from an online stroke forum. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016814 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plant SE, Tyson SF, Kirk S, et al. What are the barriers and facilitators to goal-setting during rehabilitation for stroke and other acquired brain injures? A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Clin Rehabil 2016;30:921–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White CI, Korner-Bitensky N, Rodrigue N, et al. Barriers and facilitators to caring for individuals with stroke in the community: the family’s experience. Can J Neurosci Nurs 2007;29:5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams RJ, Ellis C, Magwood G, et al. Addressing racial disparities in stroke: the wide spectrum investigation of stroke outcome disparities on multiple levels (WISSDOM). Ethn Dis 2017;28:61–68. 10.18865/ed.28.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000;23:334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jenkins C, Myers PJ, Heidari K, et al. Diabetes-related disparities in South Carolina: challenges, programs, progress, and recommendations for future efforts. J S C Med Assoc 2010;106:50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saldana J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 2nd ed Washington, D.C.: Sage Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. 3rd ed Washington, D.C.: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hesse-Biber SN, Leavy P. The practice of qualitative research. 2nd ed Washington, D.C.: Sage Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glass TA, Matchar DB, Belyea M, et al. Impact of social support on outcome in first stroke. Stroke 1993;24:64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuzaki S, Hashimoto M, Yuki S, et al. The relationship between post-stroke depression and physical recovery. J Affect Disord 2015;1:56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellis C, Egede LE. Stroke recognition among individuals with stroke risk factors. Am J Med Sci 2009;337:5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellis C, Egede LE. Ethnic disparities in stroke recognition in individuals with prior stroke. Public Health Rep 2008;123:514–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack. A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014;45:2160–2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song Z. Accountable care organizations in the U.S. healthcare system. J Clin Outcomes Manag 2014;21: 64–371. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fisher ES, Shortell SM. Accountable care organizations. Accountable for what, to whom, and how. JAMA 2010;304:1715–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pham HH, Cohen M, Conway PH. The Pioneer accountable care organization model. Improving quality and lowering costs. JAMA 2014;312:635–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown AF, Ma GX, Miranda J, et al. Structural interventions to reduce and eliminate health disparities. Am J Public Health 2019;109:S72–S78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agurs-Collins T, Persky S, Paskett ED, et al. Designing and assessing multilevel interventions to improve minority health and reduce health disparities. Am J Public Health 2019;109:S86–S93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tucker CM, Marsiske M, Rice KG, et al. Patient-centered culturally sensitive health care: model testing and refinement. Health Psychol 2011;30:342–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]