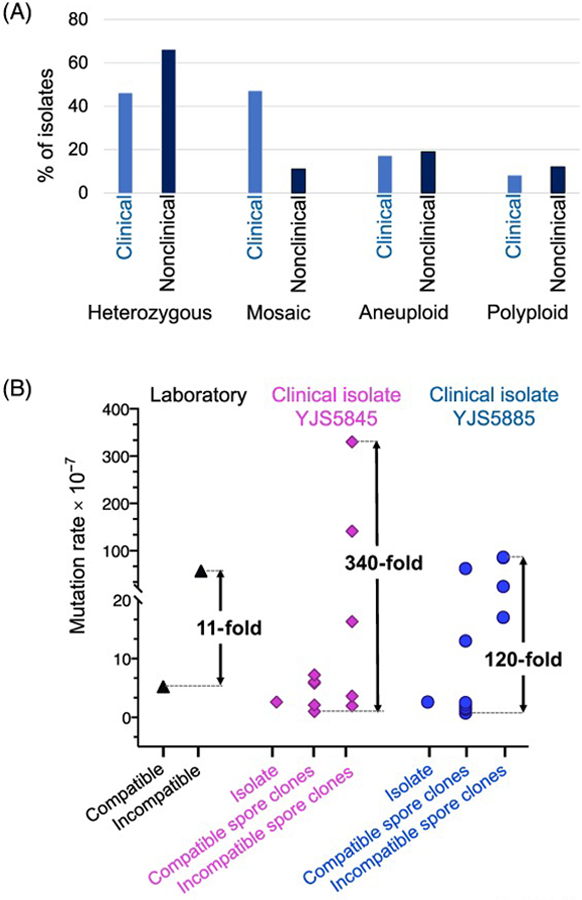

Figure 2. Genetic and phenotypic properties of clinical and nonclinical isolates of yeast.

A. Proportions of 107 clinical and 904 nonclinical isolates from the 1011 S. cerevisiae genome project [9] with a given genetic property. See Table 2 for details. For the heterozygous and polyploid categories, only natural isolates (107 clinical, 687 nonclinical) were analyzed. B. Mutation rate variation observed in a clinical isolate. Mutation rates were determined using a plasmid-based frameshift reversion assay of an MLH1-PMS1 compatible laboratory strain (S288c) and an isogenic derivative containing an incompatible MLH1-PMS1 combination. This assay detects frameshift mutations that restore the reading frame in a homopolymeric run of nucleotides inserted into KanMX. In wild-type strains, the reversion rate of such events (~10−7) [10] is considerably higher than seen for base substitutions (~5 × 10−10) [101]. Mutation rates of the heterozygous diploid clinical isolates YJS5845 and YJS5885 were also determined, as well as the rates for six compatible and five incompatible spore clones of YJS5845 and eight compatible and four incompatible spore clones of YJS5885. Larger variations in mutation rate were observed between incompatible and compatible spore clones of YJS5845 (340-fold) and YJS5885 (120-fold) compared to the S288c laboratory strain (11-fold). Adapted from [10].