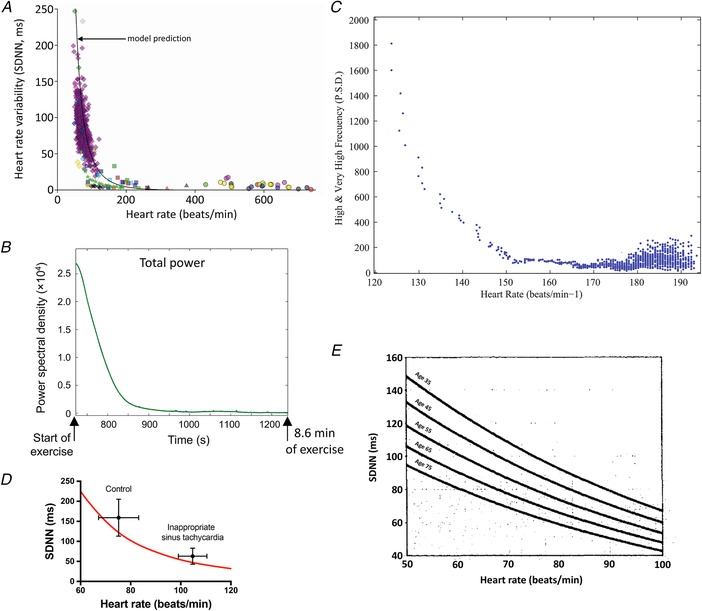

Figure 1. Heart rate dependence of HRV.

A, relationship between HRV (SDNN) and heart rate from a wide range of studies. It includes data from the healthy conscious human, athletically trained conscious human, conscious human exposed to autonomic blockade, conscious human with heart failure, conscious human with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, conscious human with myocardial infarction, conscious human heart transplant recipient, conscious mouse (wild type and transgenic), rat, Langendorff‐perfused rabbit and rat hearts, and rabbit sinus node cells (control and exposed to acetylcholine). The black line is the relationship between SDNN and heart rate predicted by the mathematical model of Monfredi et al. (2014). From Monfredi et al. (2014). B, change in HRV (total power) during high intensity exercise (cycloergometer) in an elite cyclist. Data are shown for a single individual, but similar changes were observed in 10 other elite cyclists. From Sarmiento et al. (2013). C, relationship between high frequency power (PSD) and heart rate during high intensity exercise in an elite cyclist. Data are shown for one representative subject. From Sarmiento et al. (2013). D, mean SDNN ± SD plotted as a function of mean heart rate ± SD for a group of 10 patients with inappropriate sinus tachycardia and 10 control age‐ and sex‐matched control subjects. From Castellanos et al. (1998). The red line is the relationship between SDNN and heart rate predicted by the mathematical model of Monfredi et al. (2014). E, fitted regression lines of 2 h SDNN as a function of age for 2722 male and female human subjects. Data are shown for five specific ages (35, 45, 55, 65 and 75 years) at mean heart rates between 50 and 100 beats/min. From Tsuji et al. (1996). PSD, power spectral density.