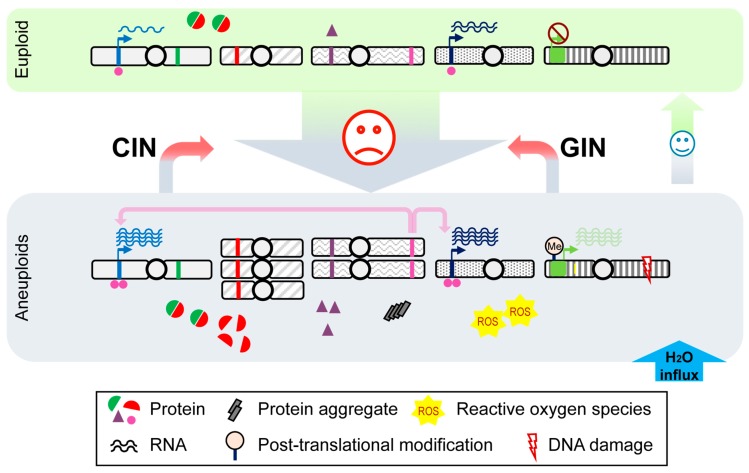

Figure 1.

A brief overview of cellular impacts from genome aneuploidization. Aneuploidization may occur when cells are under unfavorable conditions, leading to large-scale gene copy number variation. An overproduction of proteins from genes on aneuploid chromosomes causes proteome imbalance, while an excess flux of free protein subunits (e.g., red semicircles), which are not assembled into protein complexes with well-defined stoichiometry (red + green semicircles), could perturb the proteostasis network. The proteasome system could be overwhelmed due to the needs of degrading excess proteins (e.g., red semicircles and purple triangles). Increased loads of protein aggregates (grey rectangles) can be detected as a consequence of reduced Hsp90 folding capacity in aneuploidy. ROS levels are also increased, leading to oxidative stress. In addition, these extra protein subunits increase intracellular osmolarity triggering an influx of water (blue arrow), that leads to hypo-osmotic stress. As a result, an increased turgor pressure causes membrane stress. At the level of transcription, genes from euploid chromosomes (blue and dark blue bands), targeted by transcription factors encoded on aneuploid chromosomes (pink bands), could also be overexpressed; in parallel, aneuploidy may change epigenetic landscape, such as post-translational modifications (light orange flag on a gene labeled with green band), in a genome-wide manner to affect gene expression (green bands). As aneuploidy is a direct outcome of genomic instability (GIN) or chromosomal instability (CIN), it could drive further GIN and CIN from defective DNA damage repair and mitotic errors and may exacerbate the existing defective phenotypes. On the other hand, mitotic stress from GIN and CIN may continuously generate karyotype diversity in the cell population for adaptive phenotypes under stressful conditions. Once the stress is withdrawn or a gene mutation with relatively minor fitness trade-off occurs, cells may revert to the euploid state.