Abstract

Purpose: Hand-held dynamometry (HHD) can be used to evaluate strength when gold-standard isokinetic dynamometry (IKD) is not feasible. HHD is useful for measuring lower limb strength in a healthy population; however, its reliability and validity in individuals with knee osteoarthritis (OA) has received little attention. In this research, we examined the test–retest reliability and validity of HHD in older women with knee OA. We also examined the associations between reliability and symptom and disease severity. Method: A total of 28 older women with knee OA completed knee extension and flexion exertions measured using HHD and IKD. Intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC2,3), standard error of measurement, and minimal detectable change were calculated. Correlation coefficients and regressions evaluated the relationships between inter-trial differences and symptom and disease severity. Results: High test–retest reliability was demonstrated for both exertions with each device (ICC2,3 = 0.83–0.96). Variance between trials was not correlated with OA symptoms. Criterion validity was good (ICC2,3 = 0.76), but extension yielded lower agreement than flexion. Regression analysis demonstrated that true strength can be predicted from HHD measurements. Conclusions: HHD is a reliable tool for capturing knee extension and flexion in individuals with OA. Because of lower agreement, HHD might be best suited for evaluating within-subject strength changes rather than true strength scores. However, gold-standard extension strength magnitudes may reasonably be predicted from regression equations (r2 = 0.82).

Key Words: knee osteoarthritis, muscle strength dynamometer, reproducibility of results

Abstract

Objectif : la dynamométrie portative (DP) peut évaluer la force lorsque la dynamométrie isocinétique (DIC) de référence n’est pas réalisable. La DP est utile pour mesurer la force des membres inférieurs dans une population en santé, mais on n’en a pas vraiment établi la fiabilité et la validité chez les personnes atteintes d’arthrose du genou. La présente étude a porté sur la fiabilité test–retest et la validité de la DP chez les femmes âgées atteintes d’arthrose du genou. Elle a également porté sur les associations entre la fiabilité et la gravité des symptômes et de la maladie. Méthodologie : au total, 28 femmes âgées atteintes d’arthrose du genou ont effectué des efforts d’extension et de flexion du genou, qui ont été mesurés par DP et DIC. Les chercheurs ont calculé les coefficients de corrélation intraclasse (CCI2,3), l’écart-type de mesure et le changement décelable minimal. Avec les coefficients de corrélation et la régression, ils ont évalué la relation entre les différences interessai et la gravité des symptômes et de la maladie. Résultats : les chercheurs ont démontré la haute fiabilité test–retest des deux appareils à l’effort (CCI2,3 = 0,83 à 0,96). L’écart entre les essais n’était pas corrélé avec les symptômes d’arthrose. Les critères avaient une bonne validité (CCI2,3 = 0,76), mais l’extension procurait une moins bonne concordance que la flexion. L’analyse de régression a démontré qu’il est possible de prédire la véritable force à l’aide des mesures de DP. Conclusion : la DP est un outil fiable pour mesurer l’extension et la flexion du genou chez les personnes atteintes d’arthrose. En raison de sa concordance plus faible, la DP convient peut-être mieux pour évaluer les changements de force intra-individuels plutôt que les véritables scores de force. Cependant, les équations de régression peuvent raisonnablement prédire l’amplitude de force de l’extension de référence (r2 = 0,82).

Mots-clés : arthrose du genou, dynamomètre pour mesurer la force musculaire, reproductibilité des résultats

Muscle strength is critical for preventing injury and maintaining independence.1–3 In particular, lower limb muscle weakness in those with knee osteoarthritis (OA) may lead to pain and impaired mobility.4 Thus, strength is commonly measured in any research evaluating the conservative management of OA.5 In these studies, knee flexion and extension strength are typically measured using a fixed, laboratory-based isokinetic dynamometer (IKD). Although these devices are useful in research because of their high reliability and validity for measuring strength,6 they are expensive and encumbering, and thus they are often not feasible or accessible in a clinical or field-based setting.5,7 Hand-held dynamometry (HHD) may be a suitable alternative because these devices are relatively inexpensive and portable.8 HHD devices have also demonstrated high inter- and intra-rater reliability and validity for measuring lower limb strength in a healthy population.8 However, they do have limitations.

These hand-held devices are often placed on the segment adjacent to the joint of interest while an experimenter resists the isometric contraction.9 Researchers have reported that at force magnitudes exceeding 200–300 newtons (N), HHD underestimates true maximal force because the experimenter cannot adequately resist the exertion.10,11 Attaching the HHD to a belt or strap and affixing it to a stable surface has demonstrated better reliability and validity in measurement of lower limb strength than techniques requiring manual resistance.9–11

One study examined the inter-rater reliability of hip, knee, and ankle strength measured using belt fixation compared with the manual resistance provided by an experimenter.10 Reliability was consistently higher for the belt-fixed exertions than for manual resistance, and intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) ranged from 0.96 to 0.99 for the belt-fixed option and from 0.04 to 0.83 for the manual option. Inter-rater reliability was particularly poor for manually resisted knee extension exertions (ICC = 0.04). In another study, these researchers measured the validity of a belt-fixed HHD compared with an IKD in measuring lower limb strength and showed that although the HHD elicited lower force magnitudes than the IKD, the two were strongly correlated (knee strength: r = 0.75–0.88).9

The reliability and validity of HHD in strength-limited populations have also been studied. These populations have included healthy older adults,1,2 patients with advanced cancer,3 adults with knee OA awaiting arthroplasty,5 and those waiting for a total knee arthroplasty.7 For knee extension and flexion exertions, this research has generally demonstrated high reliability within (intra-rater) and between (inter-rater) raters as well as between repeated exertions (test–retest); however, there has been a reasonably large error in actual strength magnitudes.1–3,5,7 The magnitude of disagreement has been larger when larger strength values were produced, a result that has further emphasized the importance of using belt fixation when assessing lower limb strength.2,3

Disease-related factors, for example, symptoms such as pain and disease severity reflected in mobility impairments, may lead to difficulty eliciting reliable lower limb strength magnitudes. For example, experimentally induced knee pain and joint effusion reduced quadriceps muscle activation and strength.12 Moreover, a significant correlation has been demonstrated between self-efficacy for functional performance and both quadricep (r = 0.35; p = 0.01) and hamstring (r = 0.39; p = 0.004) strength.13 These OA-related symptoms may contribute to a potential variability in the ability to produce reliable lower limb strength measurements. Thus, it is particularly important to investigate whether the degree of agreement between repeated strength measurements is related to the severity of osteoarthritic symptoms or to physical dysfunction.

The primary objective of this research was to examine the test–retest reliability and validity of HHD compared with gold-standard IKD in measuring knee extension and flexion strength in older women with knee OA. The secondary objective was to determine whether the magnitude of the strength discrepancy between repeated exertions was related to symptoms (pain) and disease severity (self-reported physical function, self-efficacy, mobility, and grip strength). We expected to find a high agreement between devices and acceptable test–retest reliability for each device, with a direct relationship demonstrated between osteoarthritic symptoms and disease severity with differences in test–retest reliability. This relationship would suggest that the large variance in repeated lower limb strength measurements was due to participant-specific symptoms rather than the capabilities of the measuring device.

Methods

Participants

A total of 28 women with symptomatic knee OA participated in this study. Participants had a mean age of 66.1 (SD 8.1) years and a BMI of 28.9 (SD 4.9) kg/m2. Older women with knee OA were recruited for this study. To be eligible, participants needed to meet the American College of Rheumatology clinical classification criteria for knee OA.14 These criteria include having knee pain and at least three out of six of the following: over 50 years of age, less than 30 minutes of morning stiffness, crepitus, bony tenderness, bony enlargement, and no palpable warmth.14 Exclusion criteria were other forms of arthritis, osteoporosis-related fracture, other non-arthritic knee diseases, knee surgery, unstable heart condition or neurological condition, currently receiving cancer treatment, lower extremity injury in the previous 3 months, physician-advised restriction on physical activity, and pregnancy. If participants had OA symptoms in both knees, the most symptomatic knee was tested.

Ethics approval was obtained from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board. All participants provided written informed consent.

Primary outcome: strength

Peak knee extension and flexion strength were measured using two devices: (1) an IKD – a fixed Biodex System 3 dynamometer (Biodex Medical Systems, Shirley, NY) and (2) a HHD – an ergoFET hand-held dynamometer (Hoggan Scientific, LLC, Salt Lake City, UT). Three repetitions of extension and flexion exertions were performed with each device, from which the peaks were recorded. Each set of three exertions (extension, flexion) for each device (fixed, hand-held) was repeated twice (Trial 1, Trial 2), with exertion and device type randomized.

Fixed isokinetic dynamometer

Participants were seated with their knee joint centre aligned with the axis of rotation of the dynamometer. A padded Velcro cuff was secured firmly around their distal shank, and the moment arm (knee axis of rotation to cuff centre) was recorded. Participants’ arms were crossed over their chest. After familiarizing themselves with the protocol and a warm-up, participants completed three maximal isometric exertions with the knee angle fixed to 90°. A 90° knee angle was selected to be more reproducible in a clinical setting when a HHD is used. The three maximal exertions were completed for both flexion and extension (randomized), from which the maximal torque (newton metre, or N-m) was recorded. After all exertions were completed, participants were asked to report their knee pain on the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS). If their pain rating had elevated more than 2 points from baseline, they were asked to rest until the pain subsided.

Hand-held dynamometer

Participants were seated on a plinth, with their arms crossed over their chest. A padded cuff attached to an adjustable, seatbelt-like strap was placed around their distal shank. The position of the cuff was matched to that of the IKD. This cuff was then attached to the HHD, which was secured perpendicular to a metal door using a Powerfist triple-head 4.5-inch suction cup (Princess Auto, Winnipeg, MB). With their knee angle positioned to 90°, participants completed three maximal exertions for both flexion and extension (randomized). The peak tension measured by the HHD (in newtons) for each exertion was recorded. As with the IKD, after exertions were completed, participants were asked to rate their knee pain on the NPRS. In between the two trials, participants completed questionnaires, which provided approximately 10 minutes of rest before they repeated the exertions for each device.

Secondary outcomes

Pain and self-reported lower limb function

Pain was measured using the Pain subscale of the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) questionnaire. This 42-item questionnaire is divided into five subscales, which address pain, other disease symptoms, function in activities of daily living, function in sport and recreation, and quality of life.15 Scores are calculated on a scale ranging from 0 to 100, on which a higher score indicates fewer knee problems. The KOOS was deemed reliable (ICC > 0.75) and responsive, with high construct validity, compared with a tool (SF–36) widely used with older adults with knee OA.15

Self-reported physical function was measured using the Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS). This 20-item questionnaire is scored out of 80, with higher scores representing higher function.16 This scale has high test–retest reliability (R = 0.86) and construct validity compared with the SF–36.16

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is a behaviour-specific state that relates to personal belief about one’s ability to perform a particular activity.17 Self-efficacy was measured using the Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale (ASES). This 20-item questionnaire, which is divided into three subscales (Pain, Function, and Other Symptoms), has been reported to be valid and reliable in people with arthritis.17 The average score for each item of each subscale is calculated, and scores range from 10 to 100, with a higher score indicating higher self-efficacy.

Mobility performance

Mobility performance was assessed using the 6-minute walk test (6MWT) in a well-lit, tiled, continuous rectangular hallway with no other pedestrian traffic. This test is included in a battery recommended by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International to assess physical function in people with OA.18 Participants are instructed to walk as far as possible in 6 minutes; the maximum distance (in metres) is recorded.18 An improvement in 6MWT distance has been demonstrated in older women with OA after 12 weeks of static strengthening exercise.19,20

Grip strength

Peak grip strength of the dominant and non-dominant hands (as self-reported by participants) was captured using a Lafayette Professional Hand Dynamometer, Model 5030L1 (Lafayette Instrument Company, Lafayette, IN). The arms were adducted and elbows flexed to 90°, with the wrist positioned between 0° and 30° of extension, as described elsewhere.21 Three trials were completed for each hand, and the mean force (in kilograms) was recorded. This protocol has been shown to yield high test–retest reliability, with correlation coefficients of 0.8 or higher.

Data and statistical analysis

The average of the three peak strength repetitions was calculated for each set of extension and flexion exertion trials. This average was used, instead of the absolute peak, because it has previously demonstrated higher reliability.5 To enable comparisons between the devices, the force values captured by the HHD were converted to torque by multiplying the force (in newtons) by the measured moment arm (in metres). Moreover, limb weight corrections were performed for the torque values captured by the IKD following the manufacturer’s specifications. Statistical analyses were conducted on the mean peak torque magnitudes for extension and flexion exertions for each device (IKD, HHD) and each trial (Trial 1, Trial 2).

To address the primary research objective, the standard error of measurement (SEM), minimal detectable change (MDC), and Shrout and Fleiss (2,3) ICCs were calculated to evaluate the test–retest reliability of each of the two devices as well as the validity of the HHD compared with that of the gold-standard IKD. Specifically, to examine test–retest reliability, these measures were calculated between Trial 1 and Trial 2 for each exertion and device. To assess device validity, the peak torque produced from each extension and flexion trial was used for analysis.

ICCs were calculated between the IKD and HHD for each exertion. The SEM for each device and exertion was calculated as the root of the mean square error from a one-way analysis of variance, with participant as the factor and torque as the dependent variable. The SEM was then reported as a percentage of the mean (SEM%), as described elsewhere.22 The MDC was calculated as , where 1.96 is the z score for a 95% CI.8 Bland–Altman plots were also created and two-tailed paired t-tests (α = 0.05) calculated to evaluate reliability and validity.

Finally, to address any discrepancies that might exist between the HHD and gold-standard IKD, a linear regression was conducted to determine whether the IKD strength (Trials 1 and 2) could be adequately predicted using a linear model that included HHD strength (Trials 1 and 2). To address the secondary research question, the difference in strength between repeated trials within each device was calculated. Correlation coefficients with a Sidak correction were calculated between this inter-trial difference and each of the secondary outcome measures: KOOS Pain subscale, LEFS score, ASES score, 6MWT distance, and peak grip strength (dominant, non-dominant). Statistical analysis was conducted using Stata/IC, version 13.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Participants

Participants had varying scores on all symptom and disease severity outcomes (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Symptom and Disease Severity Outcomes

| Measure | Score, mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| KOOS Pain subscale, out of 100 | 67.3 (14.9) |

| LEFS score, out of 80 | 59.3 (10.0) |

| ASES score, out of 100 | 80.7 (13.6) |

| 6MWT, m | 534.1 (66.6) |

| Peak grip strength, dominant hand, kg | 27.6 (5.7) |

| Peak grip strength, non-dominant hand, kg | 26.2 (5.5) |

Note: Dominant hand: right, n = 25; left, n = 3.

KOOS = Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; LEFS = Lower Extremity Functional Scale; ASES = Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale; 6MWT = 6-minute walk test.

Primary outcomes: test–retest reliability and validity

High test–retest reliability between trials, as exhibited by low SEM%, low MDC, and high ICCs, was demonstrated for both knee extension and flexion with both the IKD and the HHD (see Table 2). The mean of the differences between repeated trials was less than 1.5 newton metre for each device (IKD, HHD) and exertion (knee extension, knee flexion). Using the method for repeatability described by Bland and Altman,23 which assumes a difference of zero and calculation of a repeatability coefficient, these results demonstrated that knee flexion, as measured by the HHD, had the highest repeatability with all participants within 2 SDs.

Table 2.

Test-Retest Reliability

| Device and exercise | SEM% | MDC, N-m | ICC (99% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IKD | |||

| Knee extension | 6.4 | 15.9 | 0.96 (0.91, 0.98) |

| Knee flexion | 7.1 | 7.6 | 0.93 (0.85, 0.97) |

| HHD | |||

| Knee extension | 6.8 | 14.0 | 0.95 (0.90, 0.98) |

| Knee flexion | 9.5 | 11.2 | 0.83 (0.68, 0.92) |

SEM% = standard error of measurement (percentage of mean); MDC = minimum detectable change; N-m = newton metre; ICC = intra-class correlation coefficient; IKD = isokinetic dynamometry; HHD = hand-held dynamometry.

For each of the other exertions, 26 of 28 (93%) participants were within 2 SDs; this is slightly below what is considered to be repeatable (95%).23 However, we found no significant differences between the two repeated trials for either device or exertion (p = 0.31–0.95). Moreover, the mean knee extensor torques for IKD and HHD were 90.1 newton metres and 74.3 newton metres, respectively, whereas the mean knee flexor torques were 38.4 newton metre and 42.4 newton metres. Despite the higher reliability demonstrated by the Bland–Altman analysis, knee flexion exertions were shown to have higher SEM% than knee extension exertions.

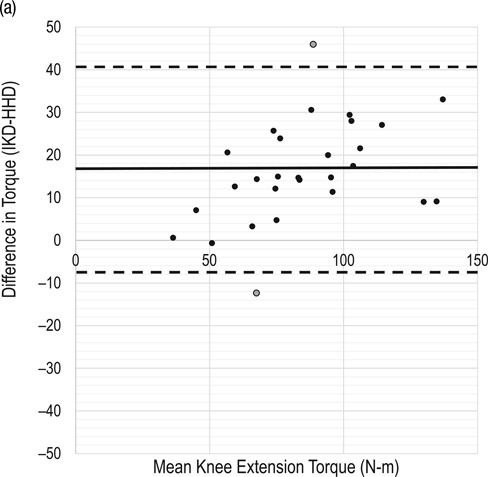

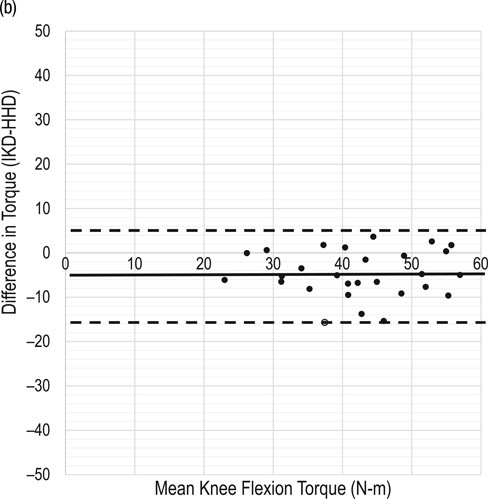

The agreement between IKD and HHD was in the range considered good.8,24 The ICC between IKD and HHD was 0.76 for both extension and flexion; however, wide CIs were elicited (extension: −0.02, 0.96; flexion: 0.38, 0.95). Overall, knee extension yielded much lower agreement than knee flexion, with the absolute difference between IKD and HHD demonstrated to be 17.1 (SD 10.6) newton metres and 5.7 (SD 4.4) newton metres, respectively. This was confirmed by the SEM% (extension, 16.7%; flexion, 11.9%) and MDC (extension, 39.3 N-m; flexion, 14.0 N-m) magnitudes. Bland–Altman analysis revealed that differences for 26 of 28 and 27 of 28 participants, for knee extension and flexion, respectively, were within 2 SDs of the mean (95% CI; see Figure 1). However, knee extension yielded a much larger magnitude of discrepancy than knee flexion.

Figure 1.

Bland–Altman plots for (a) mean knee extension torque and (b) mean knee flexion torque. In each plot, the solid line represents the mean of all differences between the peak IKD torque and peak HHD torque. The dashed lines represent mean (95% CI, or 2 × SDs). The grey circles indicate differences beyond the 95% confidence limits.

IKD = isokinetic dynamometry; HHD = hand-held dynamometry.

In addition, paired t-tests revealed differences between torque captured using the IKD compared with the HHD for both knee extension (p < 0.0001) and flexion (p = 0.0001). Despite this discrepancy between the instruments, regression analysis yielded predictive equations (extension, Equation 1; flexion, Equation 2) with reasonable predictability (extension, r2 = 0.82; flexion, r2 = 0.61), suggesting that the gold-standard value can be predicted from hand-held methods.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Secondary outcomes: relationship between reliability in strength and symptom and disease severity

We identified no significant correlations in the absolute differences between repeated exertions for knee extension or flexion torque and any of the symptom or disease severity measures for either device (see Table 3; p > 0.05). However, modest correlations were demonstrated between inter-trial differences in knee extensor torque for the IKD and both KOOS Pain subscale score (r = 0.39) and LEFS score (r = 0.45).

Table 3.

Correlation Coefficients between Inter-Trial Differences (Trial 1, Trial 2) and Secondary Outcomes for Each Device (IKD, HHD) and Exertion (Knee Extension, Flexion)

| IKD |

HHD |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Knee extension | Knee flexion | Knee extension | Knee flexion |

| KOOS Pain subscale | 0.39 | −0.03 | 0.17 | 0.00 |

| LEFS score | 0.45 | 0.11 | 0.00 | −0.05 |

| ASES score | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.08 |

| 6MWT, m | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.14 | 0.24 |

| Peak grip strength, dominant | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.28 | 0.19 |

| Peak grip strength, non-dominant | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.31 |

Note: No correlations were statistically significant; p < 0.05.

IKD = isokinetic dynamometry; HHD = hand-held dynamometry; KOOS = Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; LEFS = Lower Extremity Functional Scale; ASES = Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale; 6MWT = 6-minute walk test.

Discussion

The results of this research generally support the use of HHD for testing knee strength among older women with knee OA. Both devices demonstrated high test–retest reliability. Validity, however, was less conclusive. Although agreement between the strength acquired using the HHD and the gold-standard IKD (ICC = 0.76) was relatively high, there was extensive variation across participants. Moreover, the variance between repeated trials with each device was not strongly related to OA symptoms or clinical measures reflecting disease severity.

Reliability of strength measurement among older women with OA

In this sample of older women with symptomatic knee OA, high test–retest reliability was demonstrated (see Table 2). Knee flexion exertions had modestly higher SEM% and lower ICCs for both devices, particularly the HHD, with a lower confidence limit of 0.68 compared with 0.90 for knee extension (see Table 2). Previous researchers investigating the test–retest reliability of lower limb strength have had varied results. Although some studies have reported generally comparable reliability for knee extension and flexion,8 others have reported lower reliability for knee extension and attributed this to the larger strength magnitudes elicited by the knee extensor muscles, suggesting that stronger exertions are more difficult to reproduce.25,26 In our study, knee extensor strength still demonstrated high reliability despite showing markedly higher torque magnitudes (IKD, 90.1 N-m; HHD, 74.3 N-m) compared with flexion (IKD, 38.4 N-m; HHD, 42.4 N-m).

Recently, researchers have compared the test–retest reliability of knee flexion and extension exertion using HHD both in adults with knee OA5 and those awaiting total knee arthroplasty7 and have similarly found knee extension to have modestly higher ICCs than flexion. They attributed this finding to the difficulty of isolating the knee flexor muscles.7 However, for this study and our presented research, reliability for both exertion types within both devices is considered high, suggesting that the measurement of knee strength using HHD is reliable.

Hand-held dynamometry for strength measurement in older women with OA

IKD is considered the gold standard for strength measurement; however, its use in clinical or field-based environments is often not feasible. Good agreement was demonstrated between the IKD and HHD devices for both knee extension and flexion exertions, as demonstrated by the ICCs (0.76). However, wide ICC CIs were shown, suggesting that validity between the devices was not uniform across the measured participants, with some participants demonstrating much higher agreement than others. Also, agreement between the devices was lower for knee extension strength than for flexion strength.

Despite demonstrating the same ICC for both flexion and extension exertions, absolute differences and SEM% were much larger for knee extension (17.1 N-m; 16.7%) than for flexion (5.7 N-m; 11.9%); this was similarly demonstrated by Bland–Altman plots (see Figure 1). Interestingly, the Bland–Altman plots also revealed a non-uniform error bias for the knee extension exertions (see Figure 1). In particular, a larger torque value yielded a larger discrepancy between IKD and HHD. Thus, it appears that errors in torque produced by strong participants were larger. This lack of uniformity in the bias may have been caused by the participants’ inability to reproduce larger torque values for HHD compared with IKD, because perhaps participants felt more hesitant or less confident exerting larger knee extensor torque values for HHD than for IKD. Generally, HHD underestimated strength for knee extension exertions (26 of 28 participants) and overestimated strength for knee flexion exertions (20 of 28 participants). These findings with regards to knee extension confirm those previously reported by Martin and colleagues,2 who reported that strength measured by HHD underestimated knee extensor strength by 14.5 newton metre.

High reliability and lower validity suggest that HHD may be best used to evaluate changes in strength rather than true lower limb strength in older women with knee OA. However, despite this lower validity and non-uniformity in bias for knee extensor torque, this research also shows that gold-standard strength magnitudes (as measured using the IKD) may be predicted from HHD measurements using regression equations (see Equations 1 and 2). The knee extensor regression (Equation 1), in particular, revealed a strong association between IKD and HHD (r2 = 0.82). This association may have considerable utility in clinical or field-based cases when IKD is unavailable, but a more accurate representation of peak torque is of interest.

Relationship between variance in strength measurement and symptom and disease severity

We identified no significant correlations between the absolute variance in strength measurements obtained using either device and symptom and disease severity measures. Moderate correlations were shown between knee extensor torque (measured using the IKD) and both the KOOS Pain subscale (r = 0.39) and LEFS score (r = 0.45; see Table 3), such that those participants with lower levels of pain (i.e., a higher KOOS score) and higher mobility (i.e., a higher LEFS score) had a larger variance in inter-trial strength. However, these correlations were not statistically significant and could potentially change with a larger sample size.

Strong, negative correlations between the variance of strength and OA symptom and disease severity were expected. For example, researchers have indicated that arthrogenic muscle inhibition (AMI), which is a neurological impairment of muscle activation, may result from pain, joint effusion, joint damage, decreased motivation, or fear of injury or pain; all are associated with knee OA.12,27 AMI or activation failure can be demonstrated using a burst-superimposition technique, whereby an increase in torque is elicited when an electrical stimulus is imposed during a maximal voluntary contraction.12 Researchers demonstrated that experimentally induced pain or joint effusion (without joint damage) led to significantly reduced quadriceps strength and activation levels compared with a normal knee.12 In particular, inducing pain using a hypertonic saline injection resulted in a 13.7% reduction in strength and a 5.7% reduction in activation from the normal knee condition.

Thus, we expected that the inability to reproduce consistent strength measures would be related to OA symptoms and disease severity. However, this expectation was not supported by the data. It is likely that the absence of a relationship can be attributed to the considerable population variation in strength output, as demonstrated by the large SDs for knee extension (IKD, 28.9 N-m; HHD, 23.7 N-m) and flexion (IKD, 9.8 N-m; HHD, 9.6 N-m) exertions.

This study has certain limitations that should be considered. First, although care was taken in replicating the postures for the repeated trials, a minor variation in knee flexion angle, cuff placement, or both may have affected these results.11 Second, differences in the comfort or fit of the cuff used for each device may have influenced the participants’ exertions.9 Also, the IKD is capable of restricting the exertion to a single anterior–posterior axis, whereas with the HHD participants may have exerted some off-axis forces that it would not record. Moreover, all exertions were completed in a single testing session on the same day. Although participants were given adequate rest as needed throughout the session, it is possible that discrepancies between tests may be related to their initial apprehension about the exertions producing knee pain or to the development of muscle fatigue during the session. All strength measurements were also performed on the same day. However, given that we needed to determine a test–retest interval during which the participants were unlikely to have had any real change in strength, same-day testing was preferred to having days or weeks between tests. Finally, the experimenters were not blinded to the strength magnitudes during the collection period; this lack of blinding may have increased the risk of bias.

Conclusions

HHD can measure knee extension and flexion strength reliably, with reasonable validity, in older women with knee OA. This high reliability and the finding that strength variation was not related to OA symptoms suggests that potential muscle impairments in knee OA do not influence reliability in strength measurement. Moreover, although larger discrepancies in agreement between HHD and IKD methods were demonstrated for knee extensor strength, gold-standard strength may be predicted from regression equations (r2 = 0.82).

Key Messages

What is already known on this topic

Using hand-held dynamometry (HHD) to measure lower limb strength has been shown to be reliable and valid, particularly when a belt-fixation approach is used.

What this study adds

This research demonstrated that HHD devices can reliably measure knee extension and flexion strength in older women with knee osteoarthritis. It also showed that any deviations in repeated strength were not related to osteoarthritic symptoms. Finally, this research suggests that HHD devices may be best used to evaluate changes in knee extensor and flexor strength rather than absolute maximum strength.

Acknowledgements:

Jaclyn N. Chopp-Hurley was supported through a Canadian Institutes of Health Research fellowship award. Anthony A. Gatti was supported through the Ontario Graduate Scholarship and The Arthritis Society Doctoral Salary Award. Funding for the equipment used in this research was received by the principal investigator (MRM) through the Labarge Optimal Aging Initiative Opportunities Fund, the Canada Foundation for Innovation and the Ontario Research Fund.

References

- 1. Katoh M, Isozaki K, Sakanoue N, et al. Reliability of isometric knee extension muscle strength measurement using a hand-held dynamometer with a belt: a study of test–retest reliability in healthy elderly subjects. J Phys Ther Sci. 2010;22(4):359–63. 10.1589/jpts.22.359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martin HJ, Yule V, Syddall HE, et al. Is hand-held dynamometry useful for the measurement of quadriceps strength in older people? A comparison with the gold standard Biodex dynamometry. Gerontology. 2006;52(3):154–59. 10.1159/000091824. Medline:16645295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stone CA, Nolan B, Lawlor PG, et al. Hand-held dynamometry: tester strength is paramount, even in frail populations. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43(9):808–11. 10.2340/16501977-0860. Medline:21826388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bennell KL, Wrigley TV, Hunt MA, et al. Update on the role of muscle in the genesis and management of knee osteoarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39(1):145–76. 10.1016/j.rdc.2012.11.003. Medline:23312414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Skou ST, Simonsen O, Rasmussen S.. Examination of muscle strength and pressure pain thresholds in knee osteoarthritis: test–retest reliability and agreement. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2015;38(3):141–47. 10.1519/jpt.0000000000000028. Medline:25594517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Drouin JM, Valovich-McLeod TC, Shultz SJ, et al. Reliability and validity of the Biodex system 3 pro isokinetic dynamometer velocity, torque and position measurements. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;91(1):22–9. 10.1007/s00421-003-0933-0. Medline:14508689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koblbauer IF, Lambrecht Y, Van Der Hulst ML, et al. Reliability of maximal isometric knee strength testing with modified hand-held dynamometry in patients awaiting total knee arthroplasty: useful in research and individual patient settings? A reliability study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12(1):249–57. 10.1186/1471-2474-12-249. Medline:22040119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mentiplay BF, Perraton LG, Bower KJ, et al. Assessment of lower limb muscle strength and power using hand-held and fixed dynamometry: a reliability and validity study. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):1–18. 10.1371/journal.pone.0140822. Medline:26509265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Katoh M, Hiiragi Y, Uchida M.. Validity of isometric muscle strength measurements of the lower limbs using a hand-held dynamometer and belt: a comparison with an isokinetic dynamometer. J Phys Ther Sci. 2011;23(4):553–57. 10.1589/jpts.23.553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Katoh M, Yamasaki H.. Comparison of reliability of isometric leg muscle strength measurements made using a hand-held dynamometer with and without a restraining belt. J Phys Ther Sci. 2009;21(1):37–42. 10.1589/jpts.21.37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thorborg K, Bandholm T, Hölmich P.. Hip- and knee-strength assessments using a hand-held dynamometer with external belt-fixation are inter-tester reliable. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(3):550–5. 10.1007/s00167-012-2115-2. Medline:22773065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Palmieri-Smith RM, Villwock M, Downie B, et al. Pain and effusion and quadriceps activation and strength. J Athl Train. 2013;48(2):186–91. 10.4085/1062-6050-48.2.10. Medline:23672382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maly MR, Costigan PA, Olney SJ. Determinants of self-report outcome measures in people with knee osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(1):96–104. 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.08.110. Medline:16401446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis: classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(8):1039–49. 10.1002/art.1780290816. Medline:3741515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roos EM, Toksvig-Larsen S.. Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) – validation and comparison to the WOMAC in total knee replacement. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:1–10 10.1186/1477-7525-1-17. Medline:12801417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Binkley JM, Stratford PW, Lott SA. et al. The Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS): Scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. Phys Ther. 1999;79(4):371–83. 10.1093/ptj/79.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lorig K, Chastain RL, Ung E, et al. Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self-efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32(1):37–44. 10.1002/anr.1780320107. Medline:2912463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dobson F, Hinman RS, Roos EM, et al. OARSI recommended performance-based tests to assess physical function in people diagnosed with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2013;21(8):1042–52. 10.1016/j.joca.2013.05.002. Medline:23680877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brenneman EC, Kuntz AB, Wiebenga EG, et al. A yoga strengthening program designed to minimize the knee adduction moment for women with knee osteoarthritis: a proof-of-principle cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):1–19. 10.1371/journal.pone.0136854. Medline:26367862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kuntz AB, Karampatos S, Brenneman E, et al. Can a biomechanically-designed yoga exercise program yield superior clinical improvements than traditional exercise in women with knee osteoarthritis? Osteoarthr Cartil. 2016;24:S445–6. 10.1016/j.joca.2016.01.810. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mathiowetz V, Weber K, Volland G, et al. Reliability and validity of grip and pinch strength evaluations. J Hand Surg Am. 1984;9(2):222–6. 10.1016/s0363-5023(84)80146-x. Medline:6715829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chamorro C, Armijo-Olivo S, De Fuente C, et al. Absolute reliability and concurrent validity of hand held dynamometry and isokinetic dynamometry in the hip, knee and ankle joint: systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Med. 2017;12(1):359–75. 10.1515/med-2017-0052. Medline:29071305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(8):931–6. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.10.001. Medline:2868172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Portney L, Watkins M.. Foundations of cLinical research applications to practice. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Pearson/Prentice Hall; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jackson SM, Cheng MS, Smith AR, et al. Intrarater reliability of hand held dynamometry in measuring lower extremity isometric strength using a portable stabilization device. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2017;27:137–41. 10.1016/j.math.2016.07.010. Medline:27476066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Luedke LE, Heiderscheit BC, Williams DSB, et al. Association of isometric strength of hip and knee muscles with injury risk in high school cross country runners. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10(6):868–76. Medline:26618066. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lewek MD, Rudolph KS, Snyder-Mackler L.. Quadriceps femoris muscle weakness and activation failure in patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 2004;22(1):110–5. 10.1016/s0736-0266(03)00154-2. Medline:14656668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]