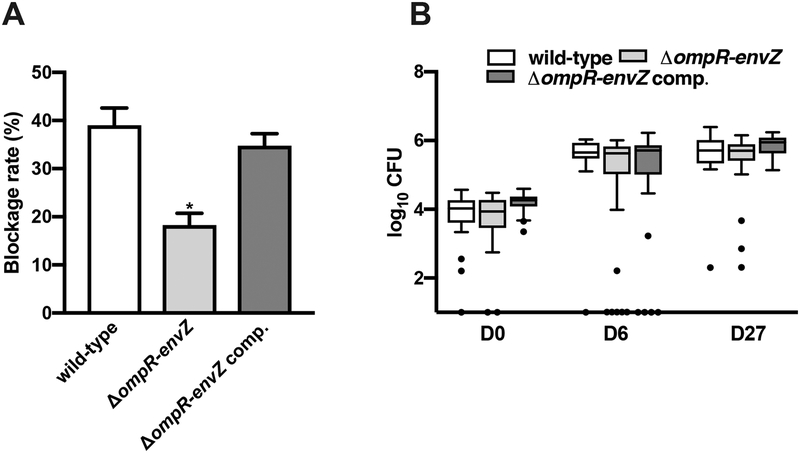

Figure 3. The Y. pestis OmpR-EnvZ system is needed for optimal flea blockage but not flea infectivity.

Comparison of the ability of the Y. pestis WT strain (white bars), the ΔompR-envZ mutant strain (light grey bars), and the same ΔompR-envZ mutant strain expressing a functional ompR-envZ operon under the control of its own promoter on a high copy plasmid (dark grey bars) to block (A) and colonize (B) fleas over a 4-week period. (A) The bars correspond to the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments with: (i) the WT strain, ΔompR-envZ::aphA, and its complemented strain; (ii) the WT strain, ΔompR-envZ::dfrB, and its complemented strain; and (iii) the WT, the two independent mutants and their complemented strains. The ΔompR-envZ mutant strain (but not its derived complemented strain) blocked significantly fewer fleas than the WT strain (*, p<0.01 in a one way analysis of variance with Holm-Sidak’s correction for multiple comparisons). (B) Box-and-whiskers (Tukey) plots representing the bacterial loads determined in 17 to 20 fleas collected immediately after feeding, and then 6 and 27 days after. The symbols indicate outliers. All three strains colonized the fleas to a similar extent (p>0.05 in a two-analysis of variance with Tukey’s correction for multiple comparisons).