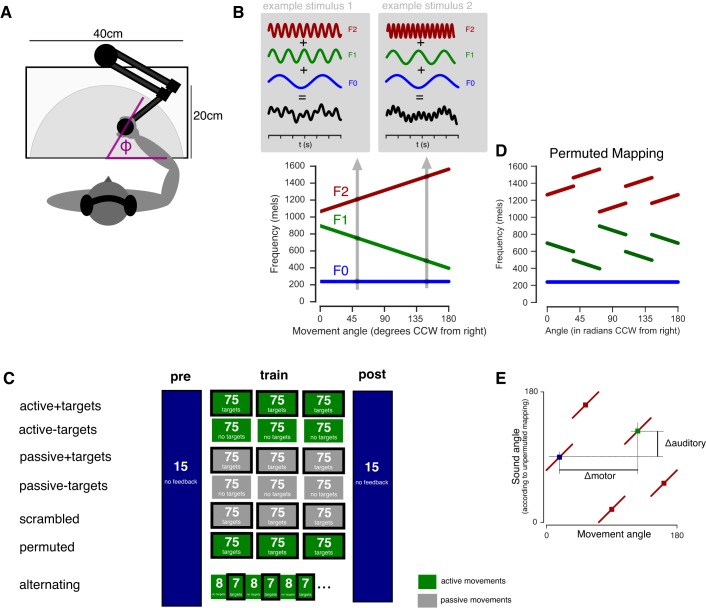

Fig. 1.

Participants made reaching movements that were turned into sounds. A: participants were seated at a planar arm movement robot and made movements from a central position to points on a half-circle. Vision was blocked during the entire experiment. B: at movement end a feedback sound was delivered that consisted of 3 pure tone oscillators (F0, F1, and F2) presented simultaneously and whose frequencies depended on the angle of the movement. CCW, counterclockwise. C: to test whether target error is required for learning, we tested conditions were targets were absent altogether (active − targets) or where targets and feedback were present but not on the same trials (alternating). To test whether active motor outflow is necessary, participants in passive groups experienced the movements of yoked active participants with or without the associated target sounds. In a scrambled condition, participants also experienced movements, targets, and feedback but the time series of these were shuffled so that the target, movement, and feedback experienced at any moment originated from different trials. D: to test whether the subjects assumed a priori that the mapping they experienced would preserve the structure of auditory and motor spaces, a permuted mapping was designed in which the workspace was divided into 5 bins and the sound-to-movement mapping was shuffled across these bins. Note that the mapping is still one-to-one. E: this permuted mapping does not preserve distances between auditory and motor spaces, so that two points can be close together in auditory space but far apart in motor space, as indicated here, or vice versa.