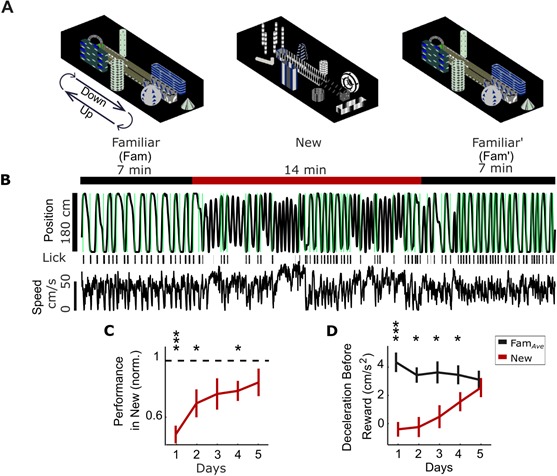

Figure 1. Behavior in new visual virtual reality (VR) environments.

(A) Head-fixed mice run to alternating ends of the VR track by controlling the movement of a floating spherical treadmill (Styrofoam ball). Mice run forward on the ball to traverse the track and rotate the ball to turn around in VR. Animals spend 7 min in a familiar environment (Fam), which is instantaneously replaced with a new environment (New) for 14 min, before returning to the same familiar environment (Fam’). The task is the same but the visual scene differs in the two environments. (B) Example mouse position in VR shows running to alternating ends of track with water rewards (green) in Fam, with worse performance in New. Lick bouts (black bars) are tracked with an electronic sensor on the lick tube. Ball speed shows similar magnitude in New and Fam environments. (C) Behavioral performance is initially impaired in New (rewards/min in New normalized to FamAve, the average performance in flanking Fam and Fam′ epochs) but improves over time. (D) Mice slow down prior to reward in the familiar environments, measured as deceleration in the 3 s window before reward. Deceleration before reward is initially lower in New but increases over days, suggesting anticipation of reward sites (N = 14 mice, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by one-sample t-test with Bonferroni-Holm Correction (C) or paired sample t-test (D)).

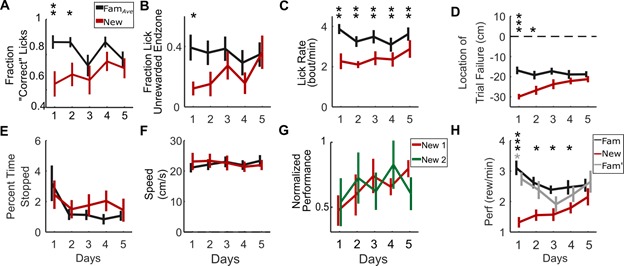

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Behavior metrics in New world.

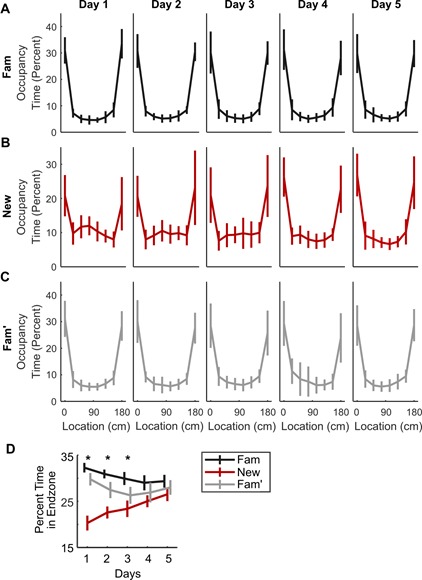

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. No track location preference in New.