Abstract

SIGNIFICANCE

The results of this study suggest that clinicians providing vergence/accommodative therapy for the treatment of childhood convergence insufficiency should not suggest that such treatment, on average, will lead to improvements on standardized assessments of reading performance after 16 weeks of treatment.

PURPOSE

The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of office-based vergence/accommodative therapy on reading performance in 9- to 14-year-old children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency.

METHODS

In a multicenter clinical trial, 310 children 9 to 14 years old with symptomatic convergence insufficiency were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to 16 weeks of office-based vergence/accommodative therapy or office-based placebo therapy, respectively. The primary outcome was change in reading comprehension as measured by the reading comprehension subtest of the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Third Edition (WIAT-III) at the 16-week outcome. Secondary reading outcomes of word identification, reading fluency, listening comprehension, comprehension of extended text, and reading comprehension were also evaluated.

RESULTS

The adjusted mean improvement in WIAT-III reading comprehension was 3.7 (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.6 to 4.7) standard score points in the vergence/accommodative therapy group and 3.8 (95% CI, 2.4 to 5.2) points in the placebo therapy group, with an adjusted mean group difference of −0.12 (95% CI, −1.89 to 1.66) points that was not statistically significant. No statistically significant treatment group differences were found for any of the secondary reading outcome measures.

CONCLUSIONS

For children aged 9 to 14 years with symptomatic convergence insufficiency, office-based vergence/accommodative therapy was no more effective than office-based placebo therapy for improving reading performance on standardized reading tests after 16 weeks of treatment.

Convergence insufficiency is a binocular vision disorder that is characterized by insufficient convergence ability and difficulty maintaining binocular fusion at near. It is estimated to affect 4 to 17% of school-aged children1–5 and is associated with a host of symptoms occurring with reading or near tasks. Children with convergence insufficiency often report symptoms related to visual discomfort (e.g., double vision, tired eyes, eye discomfort, and headaches) and reading or working up close (e.g., loss of place, frequent rereading, loss of concentration when reading, reading slowly, and trouble remembering what was read).6–10 According to their parents, children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency are more likely than children with normal binocular function to avoid or be inattentive when reading and to have difficulty completing their schoolwork and homework.11

Randomized trials have found office-based vergence/accommodative therapy to be an effective treatment for symptomatic convergence insufficiency in children,9,12,13 with resulting improvements in clinical findings and symptom severity during reading and near tasks,9 as well as parent-reported problem behaviors associated with reading and schoolwork.14 Although some have hypothesized that improvements such as these might have a positive influence on reading, either directly (e.g., improved reading comprehension and/or fluency)15–17 or indirectly (e.g., improved attention, time on reading task, and motivation),18–20 others disagree.21–23

Improvements in reading have been shown after children have been treated for convergence insufficiency.24,25 However, these studies have had variable diagnostic criteria, treatments prescribed, and outcomes; in addition, they have had methodological limitations such as small sample size and no comparison group. Addressing some of the limitations of previous studies, the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial Investigator Group conducted a pilot study to evaluate the impact of vergence/accommodative therapy on reading performance in children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency. The study had well-defined eligibility criteria, a standardized treatment protocol administered by trained therapists, and masked outcome assessments for the visual function outcomes.17 A statistically significant improvement on the reading comprehension subtest of the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Second Edition was found 8 weeks after completion of the 16-week treatment program.17 The small sample size and lack of a control group, however, precluded a definitive conclusion. Based on parent-reported distractibility and low task persistence of children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency while reading and doing schoolwork and on the improvement in reading comprehension found in our pilot study, we hypothesized that the reading domain most likely to be positively impacted by vergence/accommodative therapy was reading comprehension.

Therefore, we developed the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial–Attention & Reading Trial (CITT-ART), a randomized clinical trial to determine the effect of vergence/accommodative therapy on reading and attention in 9- to 14-year-old children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency. Herein, we report the results for reading performance. We report the effects on symptoms and clinical measures of convergence in a companion manuscript26 and those for attention in a forthcoming article.

METHODS

This trial (CITT-ART) was supported through a cooperative agreement with the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health and conducted according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki at nine clinical sites (see Acknowledgments). The protocol and informed consent forms were approved by the respective institutional review boards. The parent or guardian (subsequently referred to as “parent”) of each study participant gave written informed consent, and each child gave written assent for participation. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization was obtained from the parent. The National Eye Institute provided study oversight by the appointment of an independent data and safety monitoring committee (see Acknowledgments). The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT02207517. The full study protocol is available elsewhere,27 and the CITT-ART Manual of Procedures is available at https://u.osu.edu/cittart/.

Patient Selection and Eligibility Criteria

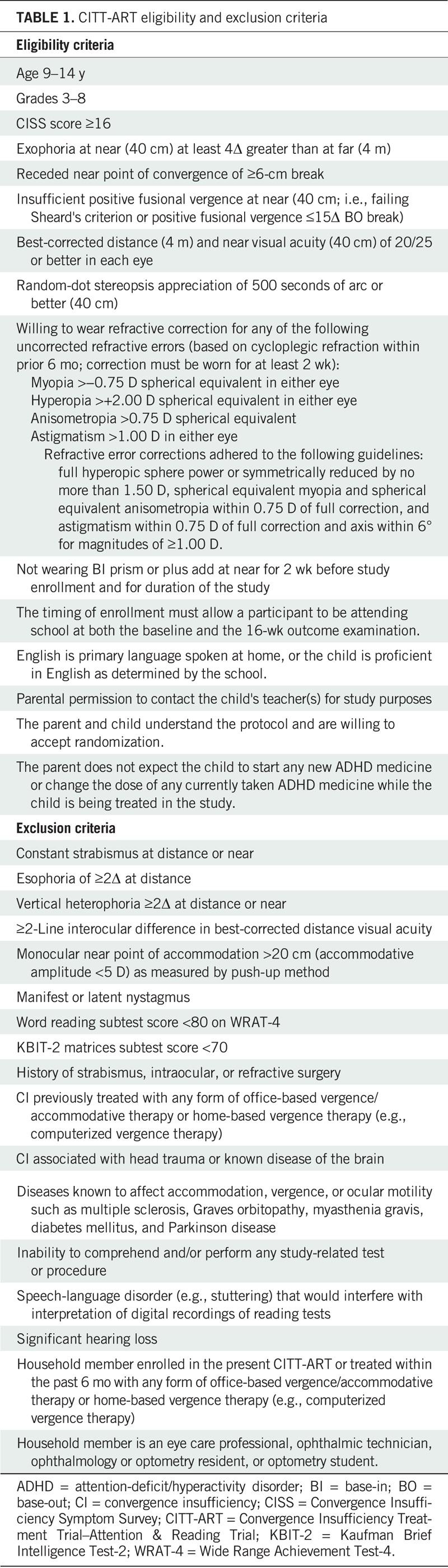

Major eligibility criteria were children 9 to 14 years of age in grades 3 to 8 who had symptomatic convergence insufficiency defined as (1) a near exodeviation (phoria or intermittent exotropia) measuring at least 4Δ larger than with distance fixation on the prism and alternate cover test, (2) a receded (≥6 cm) near point of convergence break, (3) insufficient positive fusional vergence at near (i.e., insufficient convergence amplitudes, defined as failing Sheard's28 criterion [base-out blur or break less than twice the near phoria] or minimal positive fusional vergence of ≤15Δ base-out break), and (4) a symptomatic score (≥16) on the Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey (CISS).6,7 An optical correction for significant uncorrected refractive error as determined by cycloplegic refraction was required to be worn for at least 2 weeks before enrollment (Table 1). It was required that participants be in school at enrollment and still be in school for the outcome examination (within 2 weeks). Children with cognitive impairment as suggested by standard scores of <70 on the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test-2 (KBIT-2) matrices (nonverbal) subtest29 were excluded, as were children with phonologically-based reading difficulties as suggested by a standard score <80 on the Wide Range Achievement Test-4 (WRAT-4) word reading subtest.30 A complete listing of eligibility and exclusion criteria is provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

CITT-ART eligibility and exclusion criteria

Enrollment and Randomization

Potentially eligible children were identified primarily after undergoing an eye examination by a CITT-ART investigator or other eye care provider, with a few identified via school screenings or by online study promotion. After written informed consent and assent were obtained, a CITT-ART–certified optometrist or ophthalmologist administered the aforementioned KBIT-2 and WRAT-4 tests and the following baseline visual function tests: the CISS,7,8,31 cover testing at distance and near, near point of convergence, near positive and negative fusional vergence (convergence and divergence amplitudes), monocular accommodative amplitude, monocular accommodative facility with ±2.00-D lenses, and near vergence facility (12Δ base-out and 3Δ base-in). All near vision tests were performed at 40 cm. For children who remained eligible, the AIMSweb reading curriculum–based measures (R-CBM) oral reading fluency and the AIMSweb maze tests (see Secondary Reading Outcome Measures for descriptions) were administered after vision testing was completed.

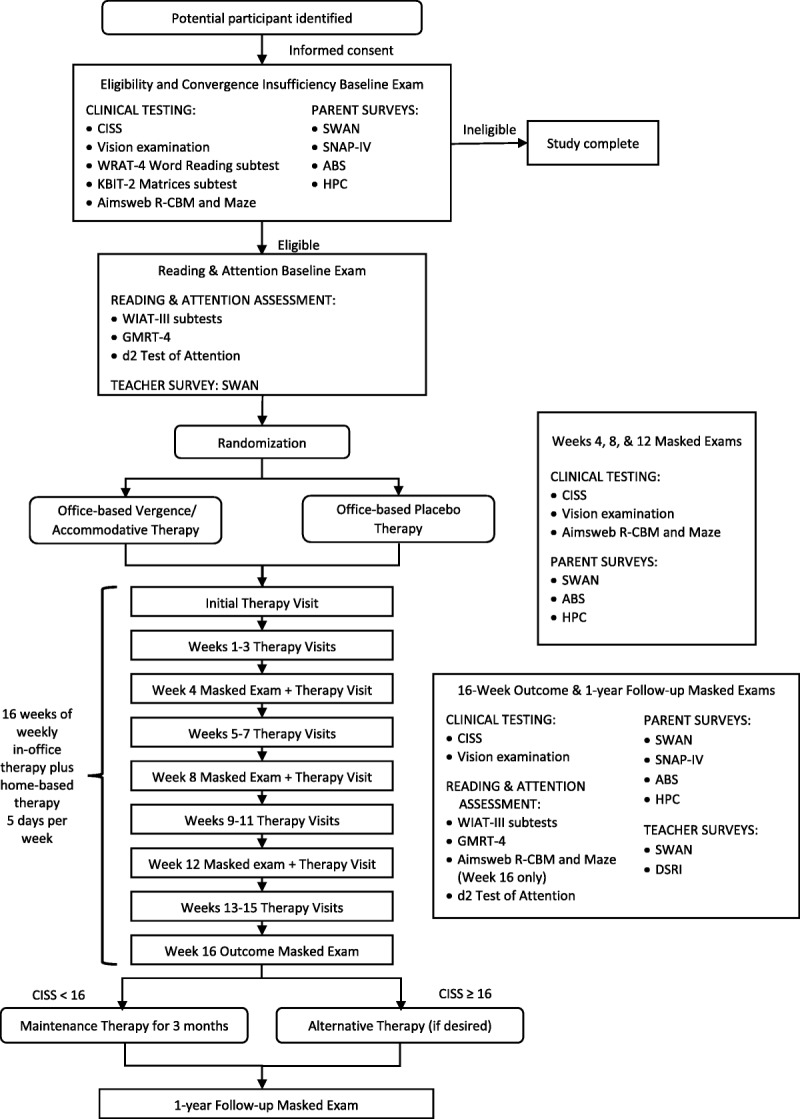

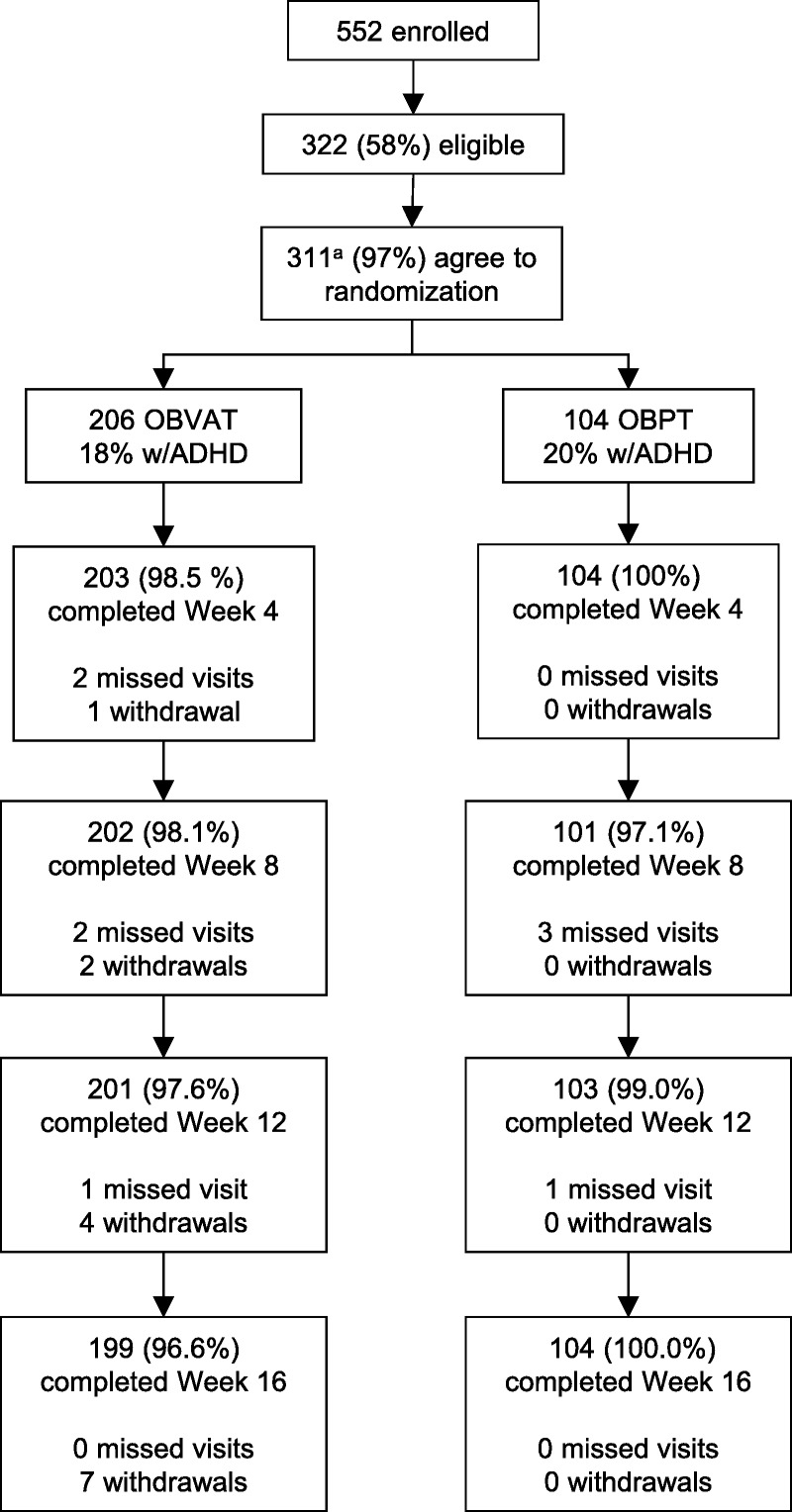

Eligible children were then scheduled for a second visit for randomization and CITT-ART baseline reading testing (Fig. 1; descriptions follow). The second visit was conducted at least 2 weeks after the start of school and within 14 days of eligibility/baseline vision testing. Participants were randomly allocated using a permuted block design stratified by site and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder status (yes/no) in a 2:1 allocation ratio of office-based vergence/accommodative therapy (hereafter referred to as vergence/accommodative therapy) or office-based placebo therapy (hereafter referred to as placebo therapy) using the Research Electronic Data Capture32 system at the Ohio State University. Block sizes of 3, 6, and 9 were used to conceal the sequence of treatment assignments.

FIGURE 1.

Eligibility testing and examination visit sequence for the CITT-ART randomized clinical trial. ABS = Academic Behavior Survey; Aimsweb R-CBM and Maze = AIMSweb Reading-Curriculum–Based Measures and AIMSweb Maze test; CISS = Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey; CITT-ART = Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial–Attention & Reading Trial; DSRI = Documentation of School Reading Instruction form; GMRT-4 = Gates-MacGinitie Reading Tests, Fourth Edition; HPC = Homework Problems Checklist; KBIT-2 = Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition; SNAP-IV = Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Checklist for DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition); SWAN = Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD Symptoms and Normal Behavior Scale; WIAT-III = Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Third Edition; WRAT-4 = Wide Range Achievement Test, Fourth Edition.

Reading Test Battery

Primary Reading Outcome Measure: WIAT-III Reading Comprehension Subtest

The primary outcome was the change in reading comprehension from baseline to the 16-week outcome visit on the reading comprehension subtest of the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Third Edition (WIAT-III).33 This subtest contains passages of increasing length and difficulty, read silently or aloud by the examinee, followed by oral comprehension questions for each passage.

The WIAT-III provides standardized scores based on national norms derived from a representative sample of children in the United States. All WIAT-III subtests used in this study have reliability coefficients ranging from 0.79 to 0.91 for grades 3 through 8.34

Secondary Reading Outcome Measures

The secondary reading outcome measures included word identification/decoding, oral reading fluency, and listening comprehension; these were assessed using the WIAT-III subtests of word reading, pseudoword decoding, oral reading fluency, and listening comprehension. There were three secondary reading comprehension tests: the reading comprehension subtest of the Gates-MacGinitie Reading Tests, Fourth Edition (GMRT-4)35 that evaluates reading comprehension using extended text; the AIMSweb R-CBM test of oral reading fluency; and the AIMSweb maze test (a measure of silent reading fluency with comprehension).

Word identification and decoding skills were measured using the WIAT-III word reading and pseudoword decoding subtests, respectively. The word reading subtest is an untimed measure in which a list of words of increasing difficulty is read. The pseudoword decoding subtest is an untimed measure of the ability to read nonsense words that follow the rules of English spelling. Because each nonsense word is by definition unfamiliar, this task measures the ability to use phonics to read unknown words.

Reading fluency was measured using the WIAT-III oral reading fluency subtest, which measures the rate and accuracy of reading grade-level text. The WIAT-III listening comprehension subtest has two parts. The first is a measure of receptive vocabulary in which the child selects from four pictures the one that best matches the word spoken aloud by the examiner. For the second part, the child answers questions about passages presented by audio recordings (oral discourse comprehension). The standard score for the listening comprehension subtest is a composite of these two parts. In contrast, growth scale value scores are provided separately for the two parts of the test (receptive vocabulary and oral discourse).

Reading comprehension of extended text was measured using a computer-administered version of the reading comprehension subtest of the GMRT-4.35 We reasoned that reading extended text passages might place increased demands on the visual system compared with reading the shorter passages of the WIAT-III reading comprehension subtest. For the GMRT-4, participants read passages independently and then responded to multiple-choice questions regarding the passages. The reliability coefficients range from 0.91 to 0.94 for grades 3 through 8.36 Normal curve equivalent scores were used for data analysis; these are standardized scores ranging from 1 to 100 that are normed to a mean of 50 with a standard deviation of 21.06.

In addition to the aforementioned reading tests, which were administered at baseline and the 16-week outcome visit, growth in oral reading fluency and silent reading fluency with comprehension were measured through repeated administrations of the AIMSweb R-CBM oral reading fluency test and the AIMSweb maze test37 at baseline and the 4-, 8-, 12-, and 16-week visits. Educators commonly use repeated administration of curriculum-based measures like these to monitor reading progression over the academic year.38 For the AIMSweb R-CBM oral reading fluency test, the child reads orally from grade-level passages for 1 minute; the score is the number of words read correctly. Reliability coefficients exceed 0.93 for grades 3 through 8.37 The AIMSweb maze test measures silent reading fluency with comprehension; it is a multiple-choice task that the examinee completes while reading passages silently. The first sentence of each passage is presented intact; thereafter, every seventh word is omitted, and the child selects the missing word from three choices. The score is the number of items correctly completed in 3 minutes. Test-retest reliability coefficients for grades 3 through 8 range from 0.70 to 0.78. Standardized z scores (mean [standard deviation], 0 [1]) were used for data analysis and are calculated based on the time of testing (fall, winter, or spring).

We hypothesized that there would be differential effects on the secondary measures of reading in this study. We expected an improvement in reading comprehension and reading fluency based on the findings of our pilot study17 and because we hypothesized that improving symptoms associated with convergence insufficiency would make accessing text easier and more comfortable with subsequent improvements in reading fluency and comprehension. Conversely, we did not expect word reading, phonological decoding, or listening comprehension to be affected by vergence/accommodative therapy.39 Word reading and phonological decoding are influenced primarily by language-based processes such as phonological processing,39,40 and listening comprehension does not involve visual stimuli. The expected lack of treatment effect on word reading was endorsed by a nonsignificant improvement for word reading in our pilot study.17

Administration and Scoring of Reading Measures

The CITT-ART Reading Center was responsible for the training, certification, and annual recertification of the reading examiners at the clinical sites and the scoring of the reading assessments. Experienced personnel provided the site-based reading examiners with a combination of face-to-face and technology-facilitated training in the standardized administration of the reading tests.

All reading measures were individually administered to participants in a quiet location by a masked reading examiner. Testing sessions were audio recorded and transmitted to the Reading Center for scoring verification. Masked personnel at the Reading Center monitored the administration and scoring of the tests by listening to the digital recordings of all test administrations; ongoing feedback was provided to the clinical site reading examiners. Each AIMSweb R-CBM oral reading fluency passage was rescored by a trained masked grader using the audio recording, and two graders scored each AIMSweb maze test. For both of the AIMSweb measures, the raw score was used for determining the normative scores.

Teacher Survey

To document the amount and nature of reading tutoring and other supplemental services provided to participants by the school outside of regular classroom instruction, participants' teachers were asked to complete a study form called the Documentation of School Reading Instruction (DSRI) within 2 weeks of the 16-week outcome examination. The DSRI form administered in this study was adapted from one used in multiple field-based studies of reading.41,42

Treatment

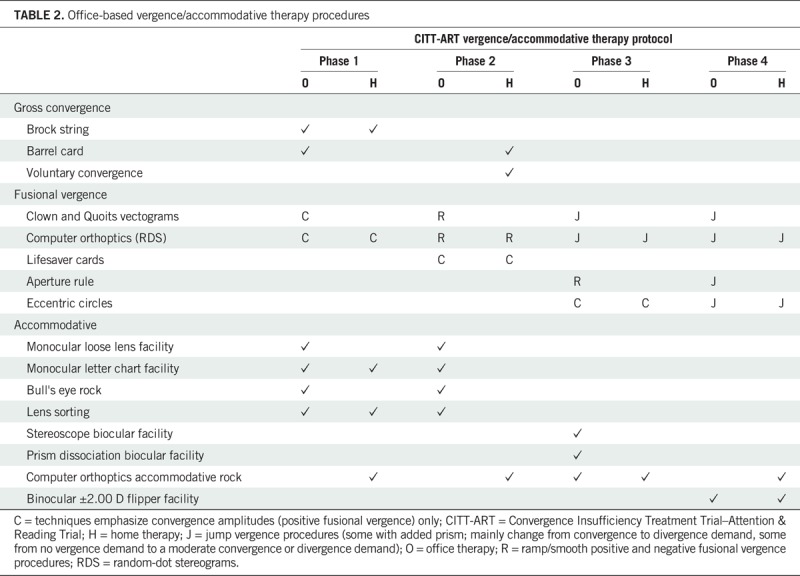

The therapy protocol comprised 16 weekly, 60-minute in-office therapy sessions performed under the supervision of a CITT-ART trained and certified therapist who followed a standardized, sequential protocol as described in the CITT-ART Manual of Procedures. Therapist contact time and prescribed treatment time in the office and at home were the same for both groups, and identical efforts were made to foster participant motivation and collaborative engagement for participants in both treatment groups. At each office visit, four to five therapy procedures were performed, with two procedures prescribed to be completed at home for 15 minutes a day, 5 days per week. The vergence/accommodative therapy procedures have been described previously13 and are shown in Table 2. The placebo therapy procedures were intended to provide similar visual demands except for stimulation of vergence or accommodation beyond that resulting normally from a participant's near viewing distance.

TABLE 2.

Office-based vergence/accommodative therapy procedures

Follow-up Examinations, Masking, and Treatment Adherence

Follow-up visits were conducted after 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks of therapy had been completed (hereafter referred to as the 4-, 8-, and 12-week follow-up visits and the 16-week outcome visit). Long-term follow-up visits were completed 1 year after the outcome visit and will be reported in a future article. Testing was performed with participants wearing their refractive correction (if applicable). Vision function testing was administered before therapy at the 4-, 8-, and 12-week visits (Fig. 1), and reading testing was completed after visual function testing at the 16-week outcome examination.

Visual function testing and the AIMSweb R-CBM oral reading fluency and AIMSweb maze tests were administered by a study-certified vision examiner, masked to participant treatment group and all other reading test results. At the 16-week outcome examination, a certified reading examiner masked to treatment assignment and visual function testing results administered the reading test battery completed at baseline (Fig. 1).

Both participants and examiners were masked to treatment group assignment. Although it was not possible to mask the therapists, their manner of conduct, including encouragement and feedback, was consistent for all participants.

The number of visits that a participant attended was used to determine adherence to the office-based therapy. In addition, the therapist estimated participant adherence to the prior week's prescribed home therapy based on electronic data from the home computer program, written home therapy logs, and participant and parental feedback; a five-item Likert-type scale of not at all, seldom, about half the time, most of the time, and always was used to categorize adherence. “Most of the time” and “always” were considered as adherent to the prescribed home treatment regimen for the prior week. The percentage of weeks (of 16) that each participant was judged to be adherent was calculated.

Sample Size

There were limited data available related to the expected treatment effects of vergence/accommodative therapy on reading scores; thus, an estimate of the Cohen d effect size was used to calculate sample size.43 Using a conservative effect size of 0.35, 10% loss to follow-up, and 80% power with a two-sided significance level of .05 yielded a total sample size of 324 participants (216 in vergence/accommodative and 108 in placebo therapy). Based on the observed variability at baseline in our pilot study,17 this effect size of 0.35 translates to an improvement of 4.06 points on the WIAT-III reading comprehension subtest; this effect size is comparable with the improvement in reading comprehension observed in the study by Atzmon et al.24

Statistical Analysis

All data analyses were performed using the SAS version 9.3 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC) and an α level of 0.05. Research Electronic Data Capture electronic data capture tools hosted at Ohio State University were used for data entry and management.32 Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, frequency counts) for demographic characteristics, visual function findings, and baseline reading scores of participants were compared to assess the effectiveness of randomization in balancing the treatment arms. Factors showing a clinically meaningful difference between groups were identified as potential confounders for the multivariable analyses.

An intent-to-treat analysis of all participants who completed the 16-week outcome was performed. Hierarchical linear modeling techniques with a random effect for enrollment site were used.44 The dependent variable was the change in the outcome of interest from baseline to the 16-week outcome coded such that gains/improvements are indicated by a within-subject change greater than zero. Multivariable models were constructed using forward selection (most significant in next) methodology. Variables were retained in the final model if they were significantly associated with the outcome or were determined a priori to be important for inclusion (e.g., baseline value of the outcome). Treatment group interactions with baseline values and all significant covariates were assessed for inclusion in the model; none were identified. Cohen d effect sizes (between-group difference divided by residual error from linear model) were calculated to quantify treatment effect. Using Cohen's taxonomy, an effect size greater than 0.80 represents a large treatment effect; between 0.50 and 0.80, a moderate effect; and less than 0.50, a small effect.

To facilitate comparison with typical growth on norm-referenced reading tests, we also conducted exploratory analyses to evaluate whether children in either treatment group made significant gains on reading measures from baseline to the 16-week outcome visit. For each reading measure, the estimated residual error from the hierarchical linear model was used to determine whether the within-group change differed significantly from 0. The magnitude of the change was characterized by effect size and 95% confidence intervals using methodology that controls for the inherent correlation between two measures obtained from the same individual.45 For the WIAT-III subtests, within-group improvements were evaluated using growth scale value scores. These scores are on an equal-interval, continuous scale that spans all ages and grade levels (based on item response theory), making them useful for tracking growth over time. Growth scale value scores were used in these analyses to compare participants' reading growth to those reported for typical students by Bloom and colleagues,46 who reported effect sizes using similar item response theory–based growth scores. The mean growth scale value score of 500 is anchored at grade 3. Because growth scale value scores were available only for the WIAT-III subtests, normal curve equivalent scores were used to evaluate within-group change for the GMRT-4 reading comprehension subtest, and growth for the AIMSweb measures (AIMSweb R-CBM oral reading fluency and maze) was assessed using z scores.

An additional exploratory analysis compared the between-group improvement in each reading measure for participants classified as “successfully treated” based on a composite convergence outcome defined as a normal near point of convergence (<6 cm) and normal positive fusional vergence at near (passing Sheard's28 criterion and a base-out to break value >15Δ). Contrasts within the hierarchical linear models were used, together with identified covariates to obtain the adjusted mean treatment effect for each reading outcome measure.

RESULTS

Enrollment

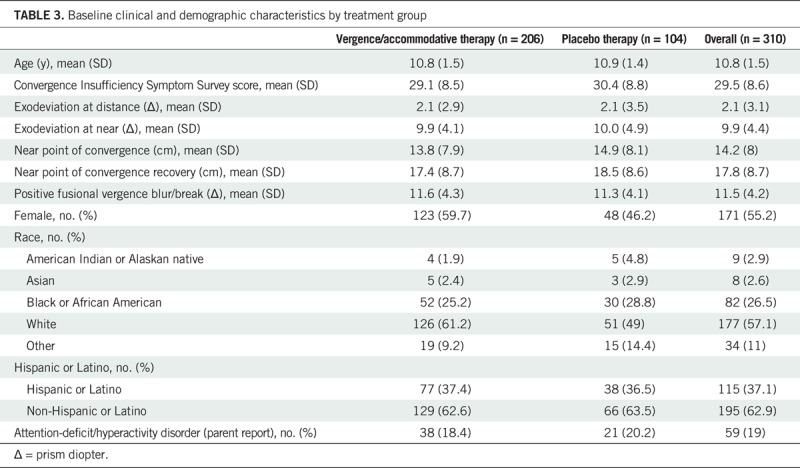

Between September 2014 and March 2017, 311 participants were enrolled. Data collected beyond baseline for one participant found to be ineligible were excluded by institutional review board mandate, resulting in 310 participants for analysis. The number enrolled at the nine sites ranged from 15 to 42 (median of 37). Mean (standard deviation) age was 10.8 (1.5) years, and 55% were female. Table 3 provides the study population demographics and baseline clinical characteristics by treatment group. Baseline characteristics were similar for both groups.

TABLE 3.

Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics by treatment group

Participant Follow-up and Adverse Events

In the vergence/accommodative and placebo therapy groups, 96.6% (199/206) and 100.0% (104/104) of participants, respectively, completed the 16-week outcome visit (Fig. 2). Because only seven participants missed their outcome visit, making the probability of bias low, an imputation analysis was not conducted. Nearly 97% of the 4921 scheduled therapy visits were completed (96.8% for vergence/accommodative therapy and 96.6% for placebo therapy; P = .58). There were no treatment-related adverse events in either group.

FIGURE 2.

Flowchart of the CITT-ART randomized clinical trial. CITT-ART = Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial–Attention & Reading Trial. aOne participant was determined to be ineligible after randomization; site’s IRB stated no data collected beyond baseline could be used.

Masking of Participants and Examiners

Eighty-seven percent (170/195) of participants assigned to vergence/accommodative therapy and 73% (75/103) assigned to placebo therapy stated that they believed they had been assigned to the active vergence/accommodative therapy. One vision examiner was unmasked after which he was recused from any future testing of that participant. No reading examiners became unmasked.

Documentation of School Reading Instruction: DSRI

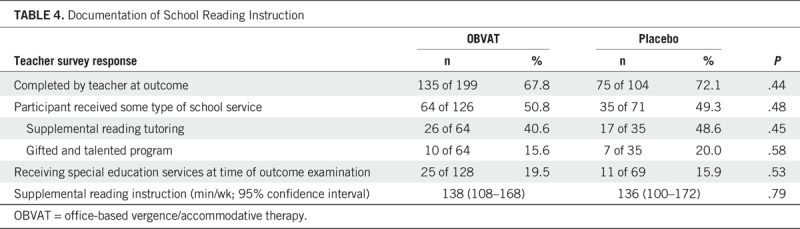

The DSRI form was completed by teachers at the 16-week outcome examination for 67.8% (135/199) and 72.1% (75/104) of participants assigned to vergence/accommodative and placebo therapy, respectively. There were no significant differences between vergence/accommodative therapy and placebo therapy (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Documentation of School Reading Instruction

Descriptive Statistics: Reading Measures at Baseline

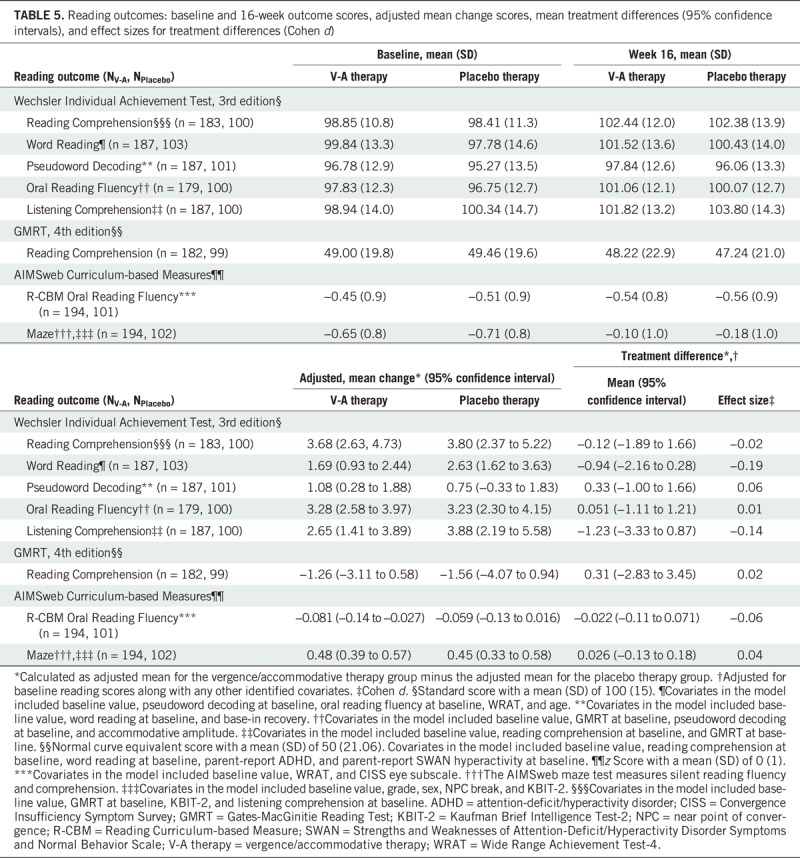

At baseline, the mean standard scores for all six WIAT-III subtests and the mean normal curve equivalent score for the GMRT-4 reading comprehension subtest were slightly below the norm for both treatment groups (Table 5). The mean z scores on the AIMSweb R-CBM oral reading fluency and the AIMSweb maze tests were nearly 0.50 and 0.75 standard deviations below the norm for both treatment groups.

TABLE 5.

Reading outcomes: baseline and 16-week outcome scores, adjusted mean change scores, mean treatment differences (95% confidence intervals), and effect sizes for treatment differences (Cohen d)

Change in Reading Test Scores at 16 Weeks

The adjusted mean change in reading test scores from baseline to the 16-week outcome for each treatment group and the between-group treatment differences and 95% confidence intervals are shown in Table 5, with a change greater than zero considered improvement and a positive treatment group difference favoring vergence/accommodative therapy.

Primary Outcome Measure: WIAT-III Reading Comprehension Subtest

At the 16-week outcome visit, the mean adjusted improvement in the WIAT-III reading comprehension subtest score was 3.68 points (95% confidence interval, 2.63 to 4.73 points) for the vergence/accommodative therapy group and 3.80 points (95% confidence interval, 2.37 to 5.22 points) for the placebo therapy group (Table 5). The mean treatment group difference of −0.12 points (95% confidence interval, −1.89 to 1.66 points) was not statistically significant. Baseline scores for the WIAT-III reading comprehension subtest; the GMRT-4 reading comprehension subtest, and the WIAT-III listening comprehension subtest, as well as the KBIT-2 nonverbal subscale, were covariates included in the hierarchical linear model.

Secondary Reading Outcome Measures

All of the secondary reading outcome data including baseline and 16-week outcome scores, adjusted mean change in scores, mean treatment group differences (95% confidence intervals), and effect sizes for treatment differences (Cohen d) are listed in Table 5. There were no statistically significant mean treatment group differences for any of the secondary reading outcome measures.

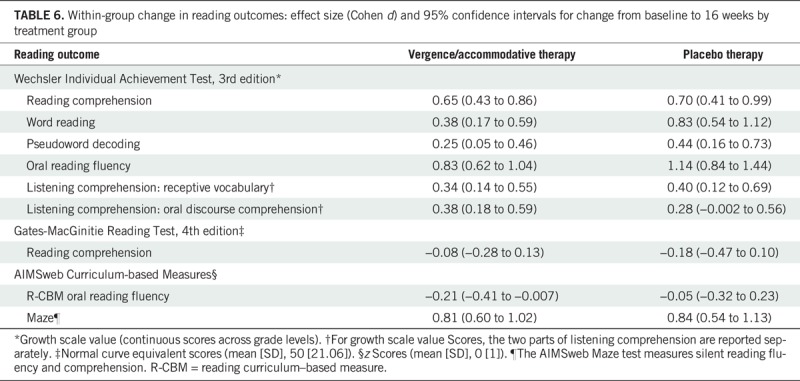

Exploratory Analyses of Within-Group Gains

In exploratory analyses, WIAT-III growth scale values were used to characterize within-group improvements, whereas changes in the GMRT-4 reading comprehension subtest and in the curriculum-based measures were calculated with the same measurement scales used for between-group comparisons. The magnitude of the observed improvement was characterized using an effect size and 95% confidence intervals.

As shown in Table 6, large statistically significant effects (d ≥ 0.80) characterized the change from baseline to 16 weeks in both the vergence/accommodative and placebo therapy groups for the WIAT-III oral reading fluency subtest and the AIMSweb maze test. In addition, large statistically significant gains on the WIAT-III word reading subtest (d = 0.83) were observed for the placebo therapy group. Gains in the WIAT-III reading comprehension subtest were moderate and statistically significant in both treatment groups. Small statistically significant effects (d < 0.50) were found for the WIAT-III pseudoword decoding and listening comprehension subtests in both groups and for the word reading subtest in the vergence/accommodative therapy group only. There were no statistically significant gains on the GMRT-4 reading comprehension subtest and the AIMSweb R-CBM oral reading fluency tests for either group.

TABLE 6.

Within-group change in reading outcomes: effect size (Cohen d) and 95% confidence intervals for change from baseline to 16 weeks by treatment group

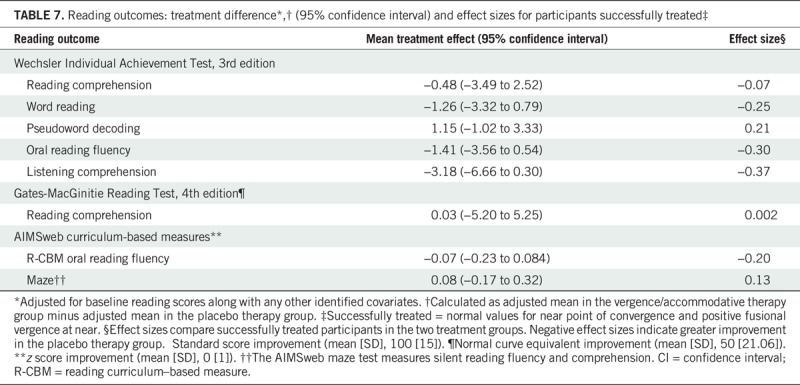

Exploratory Analysis of Treatment Response and Reading Improvement

A between-group comparison of gains in reading measures was completed for participants classified as “successfully treated” using a composite convergence outcome of normal near point of convergence and positive fusional vergence at the 16-week outcome. Using this criterion, a greater proportion of participants in the vergence/accommodative group (78.3%; 155/198) were classified as “successfully treated” compared with the placebo therapy group (28.8%; 30/104). However, there were no significant between-group treatment differences found for any reading measure (Table 7).

TABLE 7.

Reading outcomes: treatment difference*,† (95% confidence interval) and effect sizes for participants successfully treated‡

Visit Completion and Home Therapy Adherence

Of the 4921 scheduled therapy visits, 4762 (96.8%) were completed, with no difference between the vergence/accommodative (96.8%) and the placebo (96.6%) therapy groups. Mean adherence with completing the prescribed home therapy most or all of the time each week was statistically less in the vergence/accommodative (64.2%) versus the placebo therapy (76.3%) group (P < .05).

DISCUSSION

In this multicenter randomized clinical trial, 16 weeks of office-based vergence/accommodative therapy was found to be no more effective than office-based placebo therapy for improving reading performance in 9- to 14-year-old children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency. Because previous studies found that children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency reported fewer symptoms when reading9,10 and their parents reported a reduction in academic-impairing behaviors20 after treatment with vergence-accommodative therapy, we had hypothesized that office-based vergence/accommodative therapy would result in improved reading comprehension. Our study results, however, do not support this hypothesis. Similarly, all gains found for the other reading domains evaluated (word identification, decoding, reading fluency, and listening comprehension) were comparable with those found for the placebo treatment group.

Significantly greater improvements in the near point of convergence and also for positive fusional vergence were observed in the vergence/accommodative therapy group compared with the placebo therapy group.26 In addition, a significantly greater proportion of children in the vergence/accommodative group than in the placebo group (78 vs. 29%) were classified as successfully treated using the composite convergence measure of achieving both a normal near point of convergence and normal positive fusional vergence at outcome.26 However, these improvements in clinical convergence measures did not translate to a significantly greater improvement in symptoms26 or in standardized measures of reading after 16 weeks of treatment for the vergence/accommodative group compared with the placebo therapy group.

Improvements in reading performance,24,25 including better reading comprehension,24,25 speed,25 and accuracy,25 in children with convergence insufficiency after treatment with vision therapy have been reported; however, both studies had methodological differences from our study and were conducted without a placebo-control group.24,25 We are not aware of any well-designed prospective randomized clinical trials to which we can compare the present study results. In our pilot study, we found a mean improvement of 4.2 points on the reading comprehension subtest of the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Second Edition in 44 children 9 to 16 years of age with symptomatic convergence insufficiency treated with 16 weeks of vergence/accommodative therapy and tested 8 weeks after concluding the therapy. Although the 4.2-point improvement in reading comprehension is similar to the improvement (3.6 points; 95% confidence interval, 2.6 to 4.7 points) found in the current study using the WIAT-III, the pilot study did not include a control group. Given that similar improvements were found in the placebo therapy group, the present study demonstrates the importance of a placebo-control group in intervention studies.

We had hypothesized that the impact of vergence/accommodative therapy would differ based on the reading domain tested. We expected that reading comprehension and reading fluency would be positively impacted by vergence/accommodative therapy, based on our assumption that improved convergence and accommodation would make reading more comfortable and productive. Conversely, we did not expect to find improvements for word reading, phonological decoding, or listening comprehension because word reading and decoding depend heavily on language-based processes40 and listening comprehension does not involve visual stimuli. Our hypothesis of vergence/accommodative therapy having differential effects based on reading domain was not supported. Effect sizes indicate that the magnitude of difference between the two treatment groups was small and not significant for all reading domains tested.

We calculated Cohen's effect sizes to compare the growth in reading skills found in our two treatment groups with the reading growth found with typical educational instruction. Bloom and colleagues46 reported mean effect sizes ranging from 0.23 to 0.40 for expected reading growth from one grade level to the next (as a result of typical instruction and maturation in grades 3 through 8) based on composite scores of reading proficiency from nationally normed tests.

Although improvements that exceeded the benchmarks reported by Bloom et al.46 were found in both treatment groups for reading comprehension and reading fluency as measured by the WIAT-III, there were small, nonsignificant declines on the GMRT-4 reading comprehension subtest and the AIMSweb R-CBM test for oral reading fluency for both treatment arms (Table 6). This different pattern of outcomes may be related to the characteristics of the tests. In the individually administered WIAT-III reading comprehension subtest, children read either orally or silently and then respond verbally to questions asked by the examiner. In contrast, the GMRT-4 resembles a traditional achievement test in which the child reads several passages independently and responds to written multiple-choice questions. The difference in results may be because the WIAT-III does not have alternate test forms, so participants read the same passages at baseline and then 16 weeks later, whereas children read different passages at each assessment point for the AIMSweb R-CBM oral reading fluency test.

An untreated control group in the present study may have helped clarify why we found similar improvements on multiple reading measures in both treatment groups. A treatment arm that received no treatment could elucidate the role of natural history of convergence insufficiency, expected 16-week reading gains specific to our population, regression to the mean, and various placebo effects.

It is possible that both the vergence/accommodative and the placebo therapies shared some common element that improved some reading measures in both groups. The placebo therapy procedures were designed to provide visual demands similar to bona fide therapy procedures except for stimulating vergence and accommodation beyond that resulting normally from the near viewing distance. This allowed us potentially to isolate the impact of improved vergence and accommodation on reading while controlling for the duration of in-office therapy. Although the placebo therapy did not include procedures specifically directed at improving reading eye movements or visual attention, children in both groups were instructed repeatedly to keep targets clear and single. Therefore, most placebo procedures required high levels of visual attention and some involved eye movements and/or simple visual information processing tasks (e.g., visual closure, visual figure ground, visual spatial, or visual discrimination of patterns). It is possible that some of these therapy procedures that were presumably placebo may have improved some measures of reading performance.

Children in both treatment groups may have benefited from factors other than the therapies themselves, and such factors could be responsible for some or all of the reading growth found in the reading measures that improved. Placebo expectation effects and the influence of attention provided to the children by their therapists and parents, and even by their teachers who were aware of their participation in the study, could have played a role. Motivation is an important factor that has been shown to impact reading performance.47–50 Children who receive increased attention and encouragement from their parents related to reading are likely to have increased motivation for reading, particularly if both the children and the parents expect the treatment to result in reading improvement. With increased attention, children may exert greater effort, especially with one-on-one tasks with an examiner. Robust placebo effects have been shown in studies investigating novel treatments that required a large time commitment from children and their parents.51

Particular strengths of our study design included randomization, a placebo-control group, masking of examiners and participants, and a reading center for verification of reading test results. The ineffectiveness of vergence/accommodative therapy in improving reading performance did not seem to be because of poor adherence with therapy. There were very few missed therapy visits, and participant retention was excellent for both treatment arms.

Like all trials, there are several limitations to our study design. As mentioned, an untreated control group of children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency potentially could have helped to clarify the role of natural history, regression to the mean, and placebo effects. Nevertheless, a no-treatment control has its own limitations in that patients assigned to such a group know that they are not receiving treatment, which can affect self-reported outcomes and the likelihood of receiving treatment outside the study. Another limitation is that, as a group, participants performed in the average range on reading measures at baseline. One might argue that the study should have been limited to children with greater potential for reading improvement, such as younger children or those diagnosed as having mild to moderate reading problems. However, we could not limit the study to younger children because the symptom survey (CISS) used to identify our study cohort of children with “symptomatic” convergence insufficiency had not been validated in children younger than 9 years.6–8 We did not enroll solely poor readers because we did not want the study results to apply to only a small segment of the population of children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency. Nonetheless, our sample presumably includes some impaired readers based on the teacher reports that approximately 40% of the students in each treatment arm were receiving supplemental reading intervention or tutoring at school. Importantly, our sample permits generalizability to a typical distribution of children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency.

Future studies might evaluate the effectiveness of a combination of vergence/accommodation therapy and reading tutoring. The impact of instructional reading interventions may be enhanced by eliminating potential barriers to improvement such as the eye strain and fatigue associated with convergence insufficiency. There is evidence suggesting that combining literacy instruction with treatments that address underlying conditions related to reading difficulties can enhance reading outcomes.52,53

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE

Sixteen weeks of office-based vergence/accommodative therapy was no more effective than office-based placebo therapy for improving reading performance in 9-to 14-year-old children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency. For children with convergence insufficiency in this age range, identification and treatment with vergence/accommodative therapy are likely to improve vergence and accommodation function,26 which could make reading and schoolwork more comfortable. However, the results of this study suggest that clinicians providing vergence/accommodative therapy for the treatment of childhood convergence insufficiency should not suggest that such treatment, on average, will lead to improvements on standardized assessments of reading performance after 16 weeks of treatment.

Footnotes

Funding/Support: National Eye Institute (5U10EY022599; to MMS); National Eye Institute (5U10EY022601; to GLM); National Eye Institute (5U10EY022595; to SC); National Eye Institute (5U10EY022592; to MK); National Eye Institute (5U10EY022586; to ES); National Eye Institute (5U10EY022600; to RH); National Eye Institute (5U10EY022587; to MG); National Eye Institute (5U10EY022596; to RC); National Eye Institute (5U10EY022594; to KH); and National Eye Institute (5U10EY022591; to ST).

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None of the authors have reported a financial conflict of interest.

Study Registration Information: Office-based Vision Therapy for Improving Reading and Attention in Children with Convergence Insufficiency (CITT-ART: NCT02207517).

Author Contributions and Acknowledgments: Conceptualization: MMS, CD, EB, MK, GLM, SC, CC, EA, RH, MG; Data Curation: GLM, LJ-J; Formal Analysis: MMS, CD, EB, MK, GLM, SC, CC, LJ-J, EA, RH, TR; Funding Acquisition: MMS, MK, GLM, SC; Investigation: MMS, CD, EB, MK, GLM, SC, RH, MG, ES, ST, RC, KH, TR, IL; Methodology: MMS, CD, EB, MK, GLM, SC, CC, LJ-J, EA, RH, MG, ES, TR; Project Administration: MMS, MK, GLM, SC, CC; Resources: GLM; Supervision: MMS, CD, EB, MK, GLM, SC; Writing – Original Draft: MMS, TR; Writing – Review & Editing: CD, EB, MK, GLM, SC, CC, LJ-J, EA, RH, MG, ES, ST, RC, KH, TR, IL.

The Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial Writing Committee: Mitchell M. Scheiman, OD, PhD; Carolyn Denton, PhD; Eric Borsting, OD, MSEd; Marjean Kulp, OD, MS; G. Lynn Mitchell, MAS; Susan Cotter, OD, MS; Christopher Chase, PhD; Lisa Jones-Jordan, PhD; Eugene Arnold, MD; Richard Hertle, MD; Michael Gallaway, OD; Erica Schulman, OD; Susanna Tamkins, OD; Kristine Hopkins, OD, MSPH; Rachel Coulter, OD, MSEd; Tawna Roberts, OD, PhD; Ingryd Lorenzana, OD.

The Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial–Attention & Reading Trial Investigator Group Clinical Sites. Sites are listed in order of the number of participants enrolled in the study, with the number enrolled listed in parentheses preceded by the clinical site name and location. Personnel are listed as PI for principal investigator, SC for coordinator, ME-ART for masked examiner or attention and reading testing, ME-VIS for masked examiner for visual function testing, VT for vision therapist, and UnM for unmasked examiners for baseline testing.

Study Center: SUNY College of Optometry (45). Jeffrey Cooper, MS, OD (PI 06/14 to 04/15); Erica Schulman, OD (PI 04/15 to present); Kimberly Hamian, OD (ME-VIS); Danielle Iacono, OD (ME-VIS); Steven Larson, OD (ME-ART); Valerie Leung, Boptom (SC); Sara Meeder, BA (SC); Elaine Ramos, OD (ME-VIS); Steven Ritter, OD (VT); Audra Steiner, OD (ME-VIS); Alexandria Stormann, RPA-C (SC); Marilyn Vricella, OD (UnM); Xiaoying Zhu, OD (ME-VIS).

Study Center: Bascom Palmer Eye Institute (44). Susanna Tamkins, OD (PI); Naomi Aguilera, OD (VT); Elliot Brafman, OD (ME-VIS); Hilda Capo, MD (ME-VIS); Kara Cavuoto, MD (ME-VIS); Isaura Crespo, BS (SC); Monica Dowling, PhD (ME-ART); Kristie Draskovic, OD (ME-VIS); Miriam Farag, OD (VT); Vicky Fischer, OD (VT); Sara Grace, MD (ME-VIS); Ailen Gutierrez, BA (SC); Carolina Manchola-Orozco, BA (SC); Maria Martinez, BS (SC); Craig McKeown, MD (UnM); Carla Osigian, MD (ME-VIS); Tuyet-Suong Pham, OD (VT); Leslie Small, OD (ME-VIS); Natalie Townsend, OD (ME-VIS).

Study Center: Pennsylvania College of Optometry (43). Michael Gallaway, OD (PI); Mark Boas, OD, MS (VT); Christine Calvert, Med (ME-ART); Tara Franz, OD (ME-VIS); Amanda Gerrouge, OD (ME-VIS); Donna Hayden, MS (ME-ART); Erin Jenewein, OD, MS (VT); Zachary Margolies, MSW, LSW (ME-ART); Shivakhaami Meiyeppen, OD (ME-VIS); Jenny Myung, OD (ME-VIS); Karen Pollack, (SC); Mitchell M. Scheiman, OD, PhD (ME-VIS); Ruth Shoge, OD (ME-VIS); Andrew Tang, OD (ME-VIS); Noah Tannen, OD (ME-VIS); Lynn Trieu, OD, MS (VT); Luis Trujillo, OD (VT).

Study Center–The Ohio State University College of Optometry (40). Marjean Kulp, OD, MS (PI); Michelle Buckland, OD, MS (ME-VIS); Allison Ellis, BS, MEd (ME-ART); Jennifer Fogt, OD, MS (ME-VIS); Catherine McDaniel, OD, MS (ME-VIS); Taylor McGann, OD (ME-VIS); Ann Morrison, OD, MS (ME-VIS); Shane Mulvihill, OD, MS (VT); Adam Peiffer, OD, MS (ME-VIS); Maureen Plaumann, OD (ME-VIS); Gil Pierce, OD, PhD (ME-VIS); Julie Preston, OD, PhD, MEd (ME-ART); Kathleen Reuter, OD (VT); Nancy Stevens, MS, RD, LD (SC); Jake Teeny, MA (ME-ART); Andrew Toole, OD, PhD (VT); Douglas Widmer, OD, MS (ME-VIS); Aaron Zimmerman, OD, MS (ME-VIS).

Study Center: Southern California College of Optometry (38). Susan Cotter, OD, MS (PI); Carmen Barnhardt, OD, MS (VT); Eric Borsting, OD, MSEd (ME-ART); Angela Chen, OD, MS (VT); Raymond Chu, OD, MS (ME-VIS); Kristine Huang, OD, MPH (ME-VIS); Susan Parker (SC); Dashaini Retnasothie (UnM); Judith Wu (SC).

Study Center: Akron Childrens Hospital (34). Richard Hertle, MD (PI); Penny Clark (ME-ART); Kelly Culp, RN (SC); Kathy Fraley CMA/ASN (ME-ART); Drusilla Grant, OD (VT); Nancy Hanna, MD (UnM); Stephanie Knox (SC); William Lawhon, MD (ME-VIS); Lan Li, OD (VT); Sarah Mitcheff (ME-ART); Isabel Ricker, BSN (SC); Tawna Roberts, OD (VT); Casandra Solis, OD (VT); Palak Wall, MD (ME-VIS); Samantha Zaczyk, OD (VT).

Study Center: UAB School of Optometry (32). Kristine Hopkins, OD (PI 12/14 to present); Wendy Marsh-Tootle, OD, MS (PI 06/14 to 2/14); Michelle Bowen, BA (SC); Terri Call, OD (ME-VIS); Kristy Domnanovich, PhD (ME-ART); Marcela Frazier, OD MPH (ME-VIS); Nicole Guyette, OD, MS (ME-ART); Oakley Hayes, OD, MS (VT); John Houser, PhD (ME-ART); Sarah Lee, OD, MS (VT); Jenifer Montejo, BS (SC); Tamara Oechslin, OD, MS (VT); Christian Spain (SC); Candace Turner, OD (ME-ART); Katherine Weise, OD, MBA (ME-VIS).

Study Center: NOVA Southeastern University (31). Rachel Coulter, OD (PI); Deborah Amster, OD (ME-VIS); Annette Bade, OD, MCVR (SC); Surbhi Bansal, OD (ME-VIS); Laura Falco, OD (ME-VIS); Gregory Fecho, OD (VT); Katherine Green, OD (ME-VIS); Gabriela Irizarry, BA (ME-ART); Jasleen Jhajj, OD (VT); Nicole Patterson, OD, MS (ME-ART); Jacqueline Rodena, OD (ME-VIS); Yin Tea, OD (VT); Julie Tyler, OD (SC); Dana Weiss, MS (ME-ART); Lauren Zakaib, MS (ME-ART).

Study Center: Advanced Vision Care (15). Ingryd Lorenzana, OD (PI); Yesena Meza (ME-VIS); Ryan Mann (ME-ART); Mariana Quezada, OD (VT); Scott Rein, BS (ME-ART); Indre Rudaitis, OD (ME-VIS); Susan Stepleton, OD (ME-VIS); Beata Wajs (VT).

National Eye Institute, Bethesda, MD. Maryann Redford, DDS, MPH.

CITT-ART Executive Committee. Mitchell M. Scheiman, OD, PhD; G. Lynn Mitchell, MAS; Susan Cotter, OD, MS; Richard Hertle, MD; Marjean Kulp, OD, MS; Maryann Redford, DDS, MPH; Carolyn Denton, PhD; Eugene Arnold, MD; Eric Borsting, OD, MSEd; Christopher Chase, PhD.

CITT-ART Reading Center. Carolyn Denton, PhD (PI); Sharyl Wee (SC); Katlynn Dahl-Leonard (SC); Kenneth Powers (Research Assistant); Amber Alaniz (Research Assistant).

Data and Safety Monitoring Committee. Marie Diener-West, PhD, Chair; William V. Good, MD; David Grisham, OD, MS, FAAO; Christopher J. Kratochvil, MD; Dennis Revicki, PhD; Jeanne Wanzek, PhD.

CITT-ART Study Chair. Mitchell M. Scheiman, OD, PhD (Study Chair); Karen Pollack (Study Coordinator); Susan Cotter, OD, MS (Vice Chair); Marjean Kulp, OD, MS (Vice Chair).

CITT-ART Data Coordinating Center. G. Lynn Mitchell, MAS (PI); Mustafa Alrahem (student worker); Julianne Dangelo, BS (Program Assistant); Jordan Hegedus (student worker); Ian Jones (student worker); Alexander Junglas (student worker); Jihyun Lee (Programmer); Jadin Nettles (student worker); Curtis Mitchell (student worker); Mawada Osman (student worker); Gloria Scott-Tibbs, BA (Project Coordinator); Loraine Sinnott, PhD (Biostatistician); Chloe Teasley (student worker); Victor Vang (student worker); Robin Varghese (student worker).

Contributor Information

Collaborators: CITT-ART Investigator Group

REFERENCES

- 1.Letourneau JE, Ducic S. Prevalence of Convergence Insufficiency among Elementary School Children. Can J Optom 1988;50:194–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rouse MW, Borsting E, Hyman L, et al. Frequency of Convergence Insufficiency among Fifth and Sixth Graders. The Convergence Insufficiency and Reading Study (CIRS) Group. Optom Vis Sci 1999;76:643–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hussaindeen JR, Rakshit A, Singh NK, et al. Prevalence of Non-strabismic Anomalies of Binocular Vision in Tamil Nadu: Report 2 of Band Study. Clin Exp Optom 2017;100:642–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wajuihian SO, Hansraj R. Vergence Anomalies in a Sample of High School Students in South Africa. J Optom 2016;9:246–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis AL, Harvey EM, Twelker JD, et al. Convergence Insufficiency, Accommodative Insufficiency, Visual Symptoms, and Astigmatism in Tohono O'odham Students. J Ophthalmol 2016;2016:6963976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rouse M, Borsting E, Mitchell GL, et al. Validity of the Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey: A Confirmatory Study. Optom Vis Sci 2009;86:357–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borsting EJ, Rouse MW, Mitchell GL, et al. Validity and Reliability of the Revised Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey in Children Aged 9–18 Years. Optom Vis Sci 2003;80:832–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borsting E, Rouse MW, De Land PN. Prospective Comparison of Convergence Insufficiency and Normal Binocular Children on CIRS Symptom Surveys. Convergence Insufficiency and Reading Study (CIRS) Group. Optom Vis Sci 1999;76:221–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial Study Group. Randomized Clinical Trial of Treatments for Symptomatic Convergence Insufficiency in Children. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:1336–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnhardt C, Cotter SA, Mitchell GL, et al. Symptoms in Children with Convergence Insufficiency: Before and After Treatment. Optom Vis Sci 2012;89:1512–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rouse M, Borsting E, Mitchell GL, et al. Academic Behaviors in Children with Convergence Insufficiency with and without Parent-reported ADHD. Optom Vis Sci 2009;86:1169–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheiman M, Gwiazda J, Li T. Non-surgical Interventions for Convergence Insufficiency. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;CD006768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheiman M, Mitchell GL, Cotter S, et al. A Randomized Trial of the Effectiveness of Treatments for Convergence Insufficiency in Children. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borsting E, Mitchell GL, Kulp MT, et al. Improvement in Academic Behaviors After Successful Treatment of Convergence Insufficiency. Optom Vis Sci 2012;89:12–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dusek W, Pierscionek BK, McClelland JF. A Survey of Visual Function in an Austrian Population of School-age Children with Reading and Writing Difficulties. BMC Ophthalmol 2010;10:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flax N. Vision and Learning: Optometry and the Academy's Early Role, an Historical Overview. J Optom Vis Dev 1999;30:105–10. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheiman M, Chase C, Borsting E, et al. Effect of Treatment of Symptomatic Convergence Insufficiency on Reading in Children: A Pilot Study. Clin Exp Optom 2018;101:585–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garzia R, Nicholson SB, Gaines CS, et al. Effects of Nearpoint Visual Stress on Psycholinguistic Processing in Reading. J Am Optom Assoc 1989;60:38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solan HA, Shelley-Tremblay J, Ficarra A, et al. Effect of Attention Therapy on Reading Comprehension. J Learn Disabil 2003;36:556–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borsting E, Mitchell GL, Arnold LE, et al. Behavioral and Emotional Problems Associated with Convergence Insufficiency in Children: An Open Trial. J Atten Disord 2016;20:836–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Handler SM, Fierson WM, Section on Ophthalmology and Council on Children with Disabilities et al. Learning Disabilities, Dyslexia, and Vision. Pediatrics 2011;127:818–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beauchamp GR, Kosmorsky G. Learning Disabilities: Update Comment on the Visual System. Pediatr Clin North Am 1987;34:1439–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helveston EM, Weber JC, Miller K, et al. Visual Function and Academic Performance. Am J Ophthalmol 1985;99:346–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atzmon D, Nemet P, Ishay A, et al. A Randomized Prospective Masked and Matched Comparative Study of Orthoptic Treatment versus Conventional Reading Tutoring Treatment for Reading Disabilities in 62 Children. Binocul Vis Q Eye Muscle Surg 1993;8:91–106. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dusek WA, Pierscionek BK, McClelland JF. An Evaluation of Clinical Treatment of Convergence Insufficiency for Children with Reading Difficulties. BMC Ophthalmol 2011;11:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CITT-ART Investigator Group. Treatment of Symptomatic Convergence Insufficiency in Children Enrolled in the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial–Attention & Reading Trial: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Optom Vis Sci 2019;96:825–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.CITT-ART Investigator Group. Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial–Attention and Reading Trial (CITT-ART): Design and Methods. Vis Dev Rehabil 2015;1:214–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheard C. Zones of Ocular Comfort. Am J Optom 1930;7:9–25. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children. 2nd ed Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilkinson GS, Robertson GJ. Wide Range Achievement Test. 4th ed (Wrat4™) Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borsting E, Rouse MW, Deland PN, et al. Association of Symptoms and Convergence and Accommodative Insufficiency in School-age Children. Optometry 2003;74:25–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—A Metadata-driven Methodology and Workflow Process for Providing Translational Research Informatics Support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wechsler D. Examiner's Manual: Wechsler Individual Achievement Test. 3rd ed (WIAT-III) San Antonio, TX: NCS Pearson; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breaux KC. Technical Manual, Wechsler Individual Achievement Test. 3rd ed Rolling Meadows, IL: Riverside; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacGinitie WH, MacGinitie RK, Maria K, et al. Manual for Scoring and Interpretation: Gates-MacGinitie Reading Tests. 4th ed Rolling Meadows, IL: Riverside; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacGinitie WH, MacGinitie RK, Maria K, et al. Technical Report (Forms S and T): Gates-MacGinitie Reading Tests. 4th ed Itasca, IL: Riverside; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pearson Aimsweb Technical Manual. Bloomington, MN: Pearson; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shinn MR. Measuring General Outcomes: A Critical Component in Scientific and Practical Progress Monitoring Practices. Bloomington, MN: Pearson; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rayner K, Foorman BR, Perfetti CA, et al. How Psychological Science Informs the Teaching of Reading. Psychol Sci Public Interest 2001;2:31–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perfetti CA, Marron MA. Learning to Read: Literacy Acquisition by Children and Adults. Philadelphia, PA: National Center on Adult Literacy Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tamm L, Denton CA, Epstein JN, et al. Comparing Treatments for Children with ADHD and Word Reading Difficulties: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2017;85:434–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Denton CA, Fletcher JM, Taylor WP, et al. An Experimental Evaluation of Guided Reading and Explicit Interventions for Primary-grade Students At-risk for Reading Difficulties. J Res Educ Eff 2014;7:268–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analyses for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed Hillsdale, NH: Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown H, Prescott R. Applied Mixed Models in Medicine. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morris SB. Estimating Effect Sizes from Pretest-posttest-control Group Designs. Organ Res Methods 2008;11:364–86. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bloom HS, Hill CJ, Rebeck Black A, et al. Performance Trajectories and Performance Gaps as Achievement Effect-Size Benchmarks for Educational Interventions. J Res Educ Eff 2008;1:289–328. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guthrie JT, Wigfield A, Metsala JL, et al. Motivational and Cognitive Predictors of Text Comprehension and Reading Amount. Sci Stud Read 1999;3:231–56. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baker L, Wigfield A. Dimensions of Children's Motivation for Reading and Their Relations to Reading Activity and Reading Achievement. Read Res Q 1999;34:452–77. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guthrie JT, Hoa ALW, Wigfield A, et al. Reading Motivation and Reading Comprehension Growth in the Later Elementary Years. Contemp Educ Psychol 2007;32:282–313. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolters CA, Denton CA, York MJ, et al. Adolescents' Motivation for Reading: Group Differences and Relation to Standardized Achievement. Read Writ 2014;27:503–33. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arnold LE, Lofthouse N, Hersch S, et al. EEG Neurofeedback for ADHD: Double-blind Sham-controlled Randomized Pilot Feasibility Trial. J Atten Disord 2013;17:410–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chenault B, Thomson J, Abbott RD, et al. Effects of Prior Attention Training on Child Dyslexics' Response to Composition Instruction. Dev Neuropsychol 2006;29:243–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nevo E, Breznitz Z. Effects of Working Memory and Reading Acceleration Training on Improving Working Memory Abilities and Reading Skills among Third Graders. Child Neuropsychol 2014;20:752–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]