Precis:

Active patient partner engagement with SCOREboard – a diverse group of older patients with cancer, caregivers of older patients with cancer, survivors, and patient advocates – to conduct the largest randomized geriatric assessment clinical trial to date, has been shown to be feasible and resulted in tangible and invaluable benefits for both the research team and patient partners alike. Actively engaging patient partners should be an essential component in the development, conduct, and completion of all clinical research.

Keywords: stakeholders, patient advocates, patient partners

Introduction

Active engagement of stakeholder partners (patients, family members, caregivers, and organizations that are representative of the population of interest in a study), as defined by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)1, has been increasingly regarded as an essential component in research, where stakeholder experiences and perspectives can thoroughly guide and inform research processes.2-4 Participation of stakeholder partners in clinical research makes research more meaningful and relevant, increases the generalizability and attractiveness of research findings to patients and clinicians, and aids in the translation of research findings into clinical practice.3,5-8 Partner engagement is mutually beneficial to partners and researchers. Patient partners have reported feelings of empowerment and value, a sense of cohesiveness, and having a better understanding of research, which collectively resulted in positive attitudes towards clinical research.9 Researchers described having a greater understanding of patients’ needs after engaging with patient partners, bringing new insights into their research.6,9 Actively engaging stakeholder partners in clinical research should be an essential component of research planning.

Engaging patient partners in clinical research has been shown to be feasible and to have a variety of positive outcomes.10 However, in geriatric oncology research, specific mechanisms and logistics of assembling a patient and caregiver partner stakeholder group that is mutually beneficial to both the research team and the stakeholder group has not yet been thoroughly explored. Here we describe our patient partner engagement in study optimization, shape, conduct, and dissemination of research findings using PCORI’s six principles as a guide: reciprocal relationships, co-learning, partnerships, transparency, honesty, and trust.4 We also describe the mutually beneficial effect of patient and caregiver partner engagement on all individuals involved in the study processes and how this engagement shaped future attitudes towards research. Active partner engagement laid a foundation that was pivotal to the success of the “Communicating About Aging and Cancer Health” (COACH) clinical trial.11

Patient and Caregiver Partners and the COACH study

Older patients with cancer have been under-represented in oncology clinical trials due to exclusion based on chronological age and presence of aging-related conditions (e.g., chronic diseases, disabilities, and cognitive problems), thus limiting the available data on the safety and efficacy of cancer treatment in older adults.9,12 In 2012, a team of geriatric oncology researchers, led by Dr. Supriya Mohile as principal investigator (PI), received PCORI funding to conduct the largest randomized geriatric assessment (GA) clinical trial to date: the COACH trial. The GA is a validated multidimensional tool that evaluates aging-related domains; e.g. functional status and cognition, and is recommended to identify vulnerabilities not found by commonly used oncology tools when treating patients ≥ 65 undergoing chemotherapy.13 The COACH trial demonstrated that providing a summary of the GA as well as GA-guided recommendations to oncologists, patients and their caregivers improved communication about aging-related concerns.11 Additionally, COACH showed that it is possible to enroll vulnerable older adults with advanced cancer in a clinical trial, providing additional evidence that individuals should not be excluded from oncology clinical trials because of age. The success of this trial is largely attributed to active engagement of the patient and caregiver partner group from study inception to completion.

Development of the Patient/Caregiver/Advocate Stakeholder Group

PCORI emphasizes rigorous patient-driven research through active partner engagement.4 Following PCORI’s recommendations, the first such patient partner (patient/caregiver/advocate) stakeholder group in geriatric oncology – Stakeholders for Care in Oncology and Research for our Elders board (SCOREboard) – was formed with the mission to “Provide feedback and make recommendations to the University of Rochester PCORI funded research team based on the knowledge and personal experiences of SCOREboard members in order to elevate the medical care, support services and outcomes for patients 65 and older with cancer and their caregivers.”

SCOREboard was a purposefully designed diverse group that utilized members’ inherent skills and personal cancer experiences to guide the research team towards the completion of a successful clinical trial. SCOREboard members represented a wide range of races/ethnicities, educational and job backgrounds, patient advocate experiences, cancer types, cancer histories, and geographic locations. In addition, SCOREboard members directly reflected the COACH study population. Members were either 1) an older patient – patient aged 65 or older currently in treatment for any cancer stage, 2) a caregiver – caregiver of a patient aged 65 or older receiving treatment for cancer, and/or 3) a patient advocate – a person, cancer survivor or patient currently undergoing cancer treatment with demonstrated experience in cancer support, education, or research advocacy.

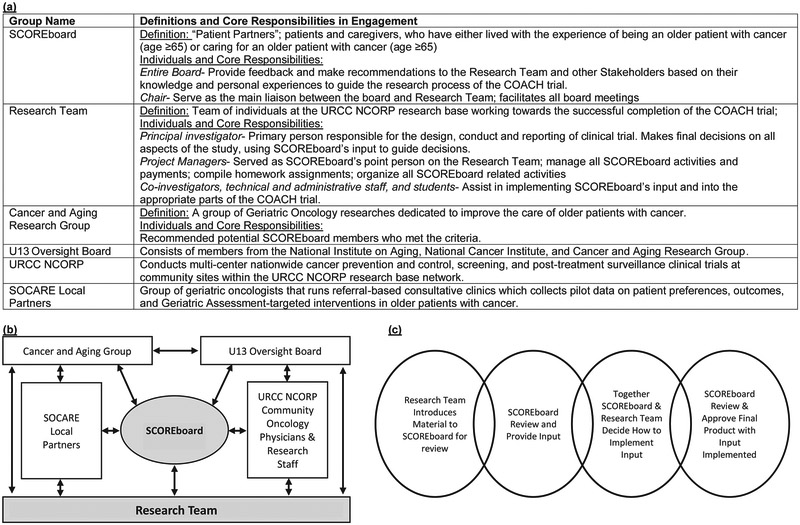

During the study design stage, the first step in developing SCOREboard was the recruitment of Ms. Canin, an experienced patient advocate member of the Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) – a national group of investigators, clinicians and other providers interested in geriatric oncology research. She worked with the research team to design the patient/caregiver advisory group included in the initial grant proposal submitted to PCORI (Figure 1) and agreed to chair the group, which was subsequently named SCOREboard. The design included methods to recruit the proposed patient/caregiver advocacy population and the roles at each stage of the study. The PCORI budget proposal included funding for consultation fees/stipends. An amount was decided through discussions with the SCOREboard chair that reasonably compensated SCOREboard members.

Figure 1:

(a) Key stakeholders and responsibilities in SCOREboard’s engagement and definitions. (b) Process for SCOREboard interactions with other stakeholder groups. (c) Process for Incorporating SCOREboard Input. U13 = U13 grant, “Geriatric Oncology Research to Improve Clinical Care”; SOCARE = Specialized Oncology Care & Research in the Elderly; URCC NCORP = University of Rochester Cancer Center NCI Community Oncology Research Program; COACH = Communicating About Aging and Cancer Health; SCOREboard = Stakeholders for Care in Oncology and Research for our Elders Board

After the PCORI grant was awarded, recruitment procedures for SCOREboard members were activated using clear guidelines for candidate qualifications as well as descriptions of tasks and responsibilities. Potential SCOREboard members, with various backgrounds as patients and/or in clinical research, advocacy, and health literacy, were recommended by CARG clinician-researchers who identified potential patients, caregivers, or advocates from their practices or by coordinators of patient and family advisory boards at CARG member institutions. Candidates completed written applications that described the goal of the COACH study and SCOREboard’s mission. The application also contained specific questions about previous patient advocate experience, whether they were a patient with cancer, a caregiver of a patient with cancer, or a survivor including their motivations for joining SCOREboard. The SCOREboard chair and PI interviewed applicant board members to ensure that, in addition to being an older patient, caregiver, and/or patient advocate, they had 1) a passion for enhancing the care experience of others, 2) the ability to recognize problems, 3) the motivation to focus energies toward solutions and/or improved services, 4) good listening and communication skills, 4) respect for diverse perspectives, 5) the ability to speak comfortably and candidly in a group, and 6) the ability to participate in regular monthly meetings as well as various committees or projects with varying time commitments.

SCOREboard began with fourteen members, age range 55–87 years representing different careers (one artist, three business professionals, one teacher, one nurse, two social workers, two administrative assistants, two non-profit administrators, and one youth service professional). Many SCOREboard members fit more than one stakeholder category: one patient, four caregivers, four patient/advocates, three patient/caregivers, and two patient/caregiver/advocates. Each SCOREboard member signed a letter of agreement, which delineated the responsibilities of both SCOREboard members and the research team. SCOREboard members committed to attending virtual meetings, completing assignments, sharing knowledge/experience/talents, and maintaining the confidentiality of the study information. The research team committed to provide bi-annual stipends, provide any assistance necessary to ensure that SCOREboard members were effectively engaged, and maintain the confidentiality of the board members.

Partners in Protocol Development and Study Start Up Process

A thoroughly planned study startup-through the demonstration of patient partner engagement principles of reciprocal relationships, which includes transparency, honesty, and trust-paved the way to the successful completion of the COACH trial. To accomplish SCOREboard’s mission, engagement was facilitated via regular virtual web-based meetings, which enabled all members to contribute equally toward the board’s mission. In addition, the research team had a dedicated administrator, who reported to both the study PI and SCOREboard chair, and assisted with technical difficulties by preparing instructions, troubleshooting technical difficulties, and providing any necessary equipment.

Keys to the Success of the Partnership with SCOREboard:

An effective SCOREboard mission statement.

A group acronym, developed by the group, that members could identify with.

Comprehensive educational materials about the project.

Regular SCOREboard monthly/bi-monthly meetings, including the PI and/or other members of the research team, scheduled well in advance.

Flexibility to adjust meeting formats and materials to accommodate the needs of the group.

Formal agendas and tasks effectively communicated to the group (e.g. ‘homework’ assignments).

Provision of adequate time to review, provide feedback and discuss projects.

Meetings facilitated by the SCOREboard chair.

Principal Investigator’s and research team’s collaborative authenticity.

Research team administrative staff available for record-keeping and assistance in facilitating all SCOREboard-related activities.

For the success of the COACH study it was essential that researchers’ goals of addressing scientific questions were effectively aligned with patients’ and caregivers’ preferences. This alignment was evident in materials SCOREboard developed to aid clinical research associates with study participant recruitment. These materials explained the study’s importance in an empathetic manner that considered patients’ and family members’ emotional well-being during the difficulties of the cancer journey. The materials were visually appealing, concise, patient friendly, and at the 6–8th grade reading level. They adequately explained the study, as well as participants’ risks and benefits (Table 1). Some of the factors SCOREboard considered while advising the research team and developing study-related materials are outlined below.

Table 1:

Examples of how collaborating with SCOREboard enhanced the study’s quality through the development of documents, study aids, and other tools

| SCOREboard Assignment | SCOREboard’s Effort and Feedback | Final Product | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Partner Group Name | Develop a name that depicts the values of the patient partner group |

|

Stakeholders for Care in Oncology and Research for our Elders Board (SCOREboard) |

| COACH logo | Work with the Strong Memorial Art Department to develop a logo to symbolize the mission of the study |

|

|

| Recruitment Brochure | Design a patient friendly brochure to introduce this study to a patient

|

|

|

| Study Documents | Review documents for completeness and usability |

|

|

| Communication Tools | Develop a tool to be used by research associates who were recruiting participants onto the COACH study |

|

|

| Dissemination Discussions | Develop dissemination plans so that results of the study could be shared with varying target audiences. |

|

|

COACH-Communicating About Aging and Cancer Health; CARG-Cancer and Aging research Group; NCORP-National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program; NCBI-National Center for Biotechnology Information; ACS-American Cancer Society; SSRN-Social Science Research Network; SCOREboard-Stakeholders for Care in Oncology and Research for our Elders Board

- Language:

- The use of appropriate language and the critical importance of authentic communication among all stakeholder groups.

- It was important to deliberate on word use such as “elderly” and “geriatric”, which some older adults find off-putting or offensive and to develop alternative ways of designating the study population.

- Patients’ general literacy level and medical understanding.

- Potential cultural influences and/or biases.

- Developing and fostering trust between potential patient and caregiver partners and the research team:

- Understanding how to break through mistrust and fears that patients might be harboring by determining past causes of mistrust.

- Establishing gentler mechanisms of communication from clinical staff in order to help potential participants feel more at ease about enrolling in the clinical trial.

- Assuring potential participants that their information will be kept confidential.

- Explaining how data obtained could help future patients.

- Creating simple and clear study aids:

- Keeping the messages accurate, simple, and limited to what is needed to aid a patient in deciding whether or not to participate.

- Study aids should not be overwhelming to patients by containing too much information; the use of “medical or institutional” terminologies should be minimal.

- “Persuade” rather than “sell” the study:

- Humanizing all forms of communication and ensuring that caution is used when “pitching” the study to potential participants.

Partners in Study Implementation and Continuation

It was anticipated that study participant recruitment would be difficult due to the frailty of the study population, but initial recruitment was even slower than expected. SCOREboard members, together with the research team and other stakeholders, evaluated study procedures and study related documents to identify unforeseen recruitment barriers. Consequently, the study was optimized by the modification of eligibility criteria, and streamlining of study-related documents, in order to reduce burden to participants and study personnel. These efforts led to a study amendment that followed by a 24-fold increase in enrollment within the first six months of amendment approval.

Maintaining stakeholder engagement during the entire study was essential to maximizing the trial’s success. Ongoing engagement offered vast opportunities to re-evaluate engagement procedures and address any unforeseen issues that might have had negative implications for the trial’s success. SCOREboard meetings occurred monthly, were one and a half to two hours long, and were facilitated by multiple web-based, video communication meeting platforms: GoToMeeting, WebEx, and Zoom. These meeting platforms allowed SCOREboard members to have real-time interactions with the research team. Individuals who were not as familiar with computer-based systems were able to join meetings via telephone. Though rarely needed, members were reimbursed if telephone calls to the virtual meetings incurred any long distance charges.

Meeting agendas planned by the study PI and the SCOREboard chair – including webinar links and call in telephone numbers – were sent to SCOREboard members one week prior to each meeting via email and/or postal service. Agendas included updates by the research team of the study’s progress, participant recruitment, study staff training, and any study-related successes, challenges, or barriers. SCOREboard members provided feedback, often based on ‘homework’ assignments to review materials such as recruitment brochures and consent forms, tips for communicating with patients and other documents needed as the study progressed. SCOREboard members also helped guide decisions about secondary analyses to be done in the dissemination phase. All meetings were recorded and transcribed and meeting minutes were sent to SCOREboard members with the reminder notice and agenda for the following meeting.

Partners in Study Closeout, Analysis and Dissemination

Active partner engagement required effective co-learning and partnership strategies. SCOREboard members had limited clinical research experience thus, substantial time was dedicated to the educational components of engagement procedures (e.g., descriptions of research processes including gathering of pilot data, applying for funding and institutional review board activities). This educational opportunity allowed SCOREboard members to feel more empowered and engaged throughout the study. As the study neared completion, many opportunities arose to conduct secondary analyses on collected data. The research team reviewed the overall themes of data collected as part of the COACH study with SCOREboard. Members then ranked themes according to what they thought could be most beneficial to older patients with cancer and their caregivers. These analyses were then prioritized by the research team. Through this process, it was determined that the emotional toll of caring for older patients with advanced cancer was a major concern and secondary analysis of COACH’s data on this topic was presented at the International Society of Geriatric Oncology 2017 Annual Conference. SCOREboard also provided editorial assistance to the resulting manuscript “Quality of Life of Caregivers of Frail Older Patients with Advanced Cancer”.14 SCOREboard members were also given the opportunity to serve as co-authors; contributing to the intellectual content, writing, and/or reviewing of ten abstracts/manuscripts based on data from the COACH study.

In a parallel effort, the COACH PI along with other CARG leaders (Dale and Hurria) received a cooperative conference grant for CARG to host the “Geriatric Oncology Research to Improve Clinical Care” conferences (2010, 2012, 2015) through the U13 funding mechanism from the National Institute on Aging. The overarching mission of the conferences was “to provide a forum for a multidisciplinary team of investigators in geriatrics and oncology to review the present level of evidence in geriatric oncology, identify areas of highest research priority, and develop research approaches to improve clinical care for older adults with cancer within the next ten years”. Seven SCOREboard members were funded by the U13 grant to attend the 2015 conference, “Design and Implementation of Intervention Studies to Maintain or Improve the Quality of Survival of Older and/or Frail Adults with Cancer” and served as coauthors on seven manuscripts.15-21 At this meeting SCOREboard members also helped to guide future research priorities in the field of geriatric oncology.

In the final year of the COACH study, a significant portion of SCOREboard’s effort was dedicated to the discussion of dissemination plans (Table 1). The discussions focused on ways to ensure that the findings reached and influenced the appropriate target audiences, including contributing researchers, trial participants, geriatric oncology healthcare providers, older patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers, patient advocacy groups, and organizations that provide services to older patients with cancer. A SCOREboard member created images to be used in dissemination materials in the future. These images were aimed at stimulating conversations with oncologists and patients and their caregivers about aging-related concerns. She stated: “I envision the imagery and the ‘essential question’ posed in the samples as a poster or cover of a flyer in which we would also encourage patients to; “Ask your doctor about a GA’ then go on to better explain what a GA entails and what research has revealed about the efficacy of its use in standardized cancer care.” Lynn Finch (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Imagery to spark conversations between oncologists, patients, and caregivers about age related concerns.

Challenges in Active Engagement

Effectively engaging patient partners requires a significant amount of time. Given the tight timeline between receiving funding and enrolling the first patient, and the fact that SCOREboard members were recruited after the receipt of grant funding (except the chair), the research team was not able to fully incorporate all recommendations from SCOREboard before the study began. We recommend, if feasible, that stakeholder groups be fully formed during the design phase, well before the receipt of study funds. The development of a successful stakeholder group requires efficient coordination between the study team, board members, and external groups (e.g. regulatory bodies, and clinical sites) (Figure 1b). It is thus beneficial to have a research team staff member (≥50% effort) dedicated to managing all aspects of engaging SCOREboard as well as their interactions with other constituents of the stakeholder group (Figure 1).

Given that more than half of SCOREboard had no prior advocacy experience and the majority of members were from non-science backgrounds, the research team was challenged to ensure that all members felt empowered to have their voices heard. SCOREboard’s chair and the study PI actively engaged with all members during group and one-on-one calls to ensure that all members were able to provide equal input and felt like a valued member of the team. Members reported that in-person meetings once or twice a year would have assisted in fostering a team environment. Solely relying on technology for the meetings was challenging, and members found technological problems disruptive and frustrating at times. Additionally, members found it difficult to retain the vast amount of information shared during meetings and that this sometimes led to feelings of lack of preparation and disempowerment. Members felt that maintaining monthly meetings, with detailed agendas sent in advance of each meeting, including specific questions for SCOREboard to answer, aided in the learning process and boosted the group’s vitality.

Additional challenges arise when working with non-research members on a clinical trial. Confidentiality and other regulations limit communication mechanisms between patient partners and study staff and participants. Intriguingly, this limitation provided SCOREboard the unique opportunity for creative thinking. SCOREboard developed innovative communication practice mechanisms with oncologists and research associates to aid them in communicating about the study when recruiting potential participants. Special webinars were held where SCOREboard members’ role played potential participants. Scripted dialogues were also developed with empathetic phrases designed to aid members of the clinical team who were recruiting potential participants at varied stages in their cancer journey (Table 1).

Effect of Active Engagement on SCOREboard Members and Valuable Takeaways

Puts et al. summarized the benefits experienced by partners who were actively engaged in clinical research. Potential benefits include feelings of empowerment, value, and changed attitudes towards clinical research.7 As the COACH study drew to a close, a special meeting was conducted to allow members to reflect on their experience and provide feedback on barriers and facilitators of engaging with the research team. SCOREboard members experienced benefits similar to the Puts et al. study and found that participation in SCOREboard was a positive educational experience (Table 2). By the end of the study, members had a broader understanding of clinical trials and the research process; not just as the final option for patients with advanced disease, but also as a mechanism to expand our knowledge of how to better prevent/treat diseases and improve quality of life. Members learned to appreciate the intricacies involved in the design and implementation of a clinical trial as well as the varying roles played by different entities: funding agencies, participants, researchers, and stakeholders.

Table 2:

Quotes from SCOREboard Members Concerning Effects of Active Engagement

| Initial Reluctances participating in Clinical Trials and Changed Attitudes |

|---|

| Quotes: |

|

| Language and Communication in Study |

| Quotes: |

|

| Takeaways/What was Learned |

| Quotes: |

|

One of the meetings toward the end of the study included time for specific reflections by SCOREboard members about their experiences throughout the study. Members reported that they were enthusiastic about engaging in the COACH trial as partners, but many recalled having reluctance about participating in any clinical trial. The reluctance was largely due to a misunderstanding of the purpose of research and distrust in researchers’ agendas (Table 2). This emphasizes the need for patient education as part of the clinical trial recruitment process, which can be achieved by incorporating patient and caregiver partner groups from the early design phase of research studies, where partners can aid researchers in destigmatizing patients’ roles in clinical trials. As a direct result of being in SCOREboard, all members reported that given the opportunity, they will participate in other stakeholder groups as partners. Additionally, SCOREboard members with initial reluctance to participate in a clinical trial, stated that they were more likely to be a trial participant if approached. Members reported feeling increased confidence in asking questions about the nature of the research, as well as their responsibilities and associated risks due to participation in a clinical trial.

Due to the quality and quantity of interactions in active engagement, SCOREboard members developed lasting friendships and built a community that provided emotional support and guidance to each other as they traveled through their individual cancer journeys. We have lost several members over the course of the COACH study. The camaraderie that exists between SCOREboard members assisted them as well as the families of the deceased members with the processing of the grief that accompanies loss. Recently the field of geriatric oncology lost an inspirational leader, Dr. Arti Hurria, who was an essential member of the COACH research team. Her death has further inspired SCOREboard and the research team to continue their work pushing the field of geriatric oncology forward in fulfilling her ultimate mission to improve the care of older adults with cancer.

Effect of Active Engagement on the Research Team and Valuable Takeaways

SCOREboard’s participation in COACH forever shaped the way the COACH research team thinks about clinical research. Efforts are now made to view each research proposal through the eyes of the study’s patient population, the individuals with the most to gain from the study’s outcomes. At the onset of every new research idea the following questions are now asked: 1) How does this impact the patient population?; 2) What are patients’ preferences?; and 3) Are the questions framed in such a way that the average patient can understand? As a direct result of the tremendous benefits of engaging with SCOREboard, all new research concepts proposed by the research team contain detailed input from SCOREboard. SCOREboard is now funded through a NIA R21/R33 to develop a national infrastructure for cancer and aging research (Dale, Hurria, Mohile). The positive outcomes of engaging with SCOREboard throughout the COACH trial was evidenced by researchers in the University of Rochester’s internal and external networks. SCOREboard’s input is highly requested by researchers at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC), and SCOREboard has aided URMC researchers in grant applications for two infrastructure funding mechanisms to advance research in the area of geriatric oncology (including the R21/R33 geriatric oncology infrastructure grant), seven clinical trials focused on geriatric oncology, and three conferences to set research priorities. Eight of these received funding, and three are pending a funding decision.

Conclusions

The diversity of SCOREboard members, along with the communality of the mission, fostered the development of special friendships, serving as the backdrop upon which the successful outcomes of engagement with SCOREboard was built. Actively engaging SCOREboard, allowed for the successful completion of a clinical trial that was widely accepted and carried out in community oncology sites throughout the United States. Furthermore, SCOREboard engagement, along with positive interactions with other stakeholders in the COACH study, led to the first study to show the ability of a geriatric assessment intervention to positively change oncology providers’ behavior and increase communication and satisfaction with communication between patients and caregivers and their oncologists about aging-related concerns.11 In addition to SCOREboard engagement having positive effects on study outcomes, this engagement encouraged members to feel empowered due to changed attitudes about clinical research. The success of this interaction requires the following elements: 1) A highly engaged Principal Investigator committed to including the perspectives of patients and caregivers; 2) An empowered and active patient partner chair with past experience in patient advocacy; 3) A research team member on the staff dedicated to partner engagement activities; 4) Funding for in-person meetings and to ensure that partners are adequately compensated for their time; 5) Clearly defined roles for partners; and 6) Opportunities for additional engagement activities.

Acknowledgements

This paper is dedicated to the memory of SCOREboard members Ray Hutchins and Robert Harrison.

We would like to graciously thank all SCOREboard members for their valuable contributions that resulted in the profound success of the COACH trial. SCOREboard members include Beverly Canin (chair), Mary Whitehead, Margaret Sedenquist, Lorraine Griggs, Lynn Finch, John Aarne, Valerie Targia, Robert Harrison, Valerie Aarne, Dorothy Dobson, Jacquelyn Dobson, Burt Court, Polly Hudson, and Ray Hutchins. We would also like to thank the patients and caregivers who participated in the COACH study as well as the research staff in the University of Rochester NCI Community Oncology Research Base network.

This work was supported by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Program contract (4634); and the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (R21 AG059206–01, UG1 CA189961, R01 CA177592, and K24 AG056589). All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors, do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee.

Footnotes

Authors’ Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No relevant conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Glossary.

- 2.Staniszewska S, Haywood KL, Brett J, Tutton L. Patient and Public Involvement in Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Evolution Not Revolution. Patient-Patient Centered Outcomes Research. 2012;5(2):79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dudley L, Gamble C, Preston J, et al. What Difference Does Patient and Public Involvement Make and What Are Its Pathways to Impact? Qualitative Study of Patients and Researchers from a Cohort of Randomised Clinical Trials. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank L, Forsythe L, Ellis L, et al. Conceptual and practical foundations of patient engagement in research at the patient-centered outcomes research institute. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(5):1033–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carman KL, Workman TA. Engaging patients and consumers in research evidence: Applying the conceptual model of patient and family engagement. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(1):25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puts MTE, Sattar S, Ghodraty-Jabloo V, et al. Patient engagement in research with older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2017;8(6):391–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woolf SH, Zimmerman E, Haley A, Krist AH. Authentic Engagement Of Patients And Communities Can Transform Research, Practice, And Policy. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(4):590–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, et al. A systematic review of the impact of patient and public involvement on service users, researchers and communities. Patient. 2014;7(4):387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Backhouse T, Kenkmann A, Lane K, Penhale B, Poland F, Killett A. Older care-home residents as collaborators or advisors in research: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2016;45(3):337–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohile SG, Hurria A, Dale W/, et al. Improving Caregiver Satisfaction With Communication Using Geriatric Assessment (GA): A University Of Rochester NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial (CRCT) International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG), 2018, Amsterdam, Netherlands: (Oral Presentation) 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scher KS, Hurria A. Under-representation of older adults in cancer registration trials: known problem, little progress. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(17):2036–2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, et al. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(22):2326–2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohile G, Xu H, Canin B, et al. The emotional toll of caregiving for older patients with advanced cancer: Baseline data from a multicenter geriatric assessment (GA) intervention study in the University of Rochester NCI Community Oncology Research Program (UR NCORP). Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(15_suppl):10042–10042. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loh KP, Janelsins MC, Mohile SG, et al. Chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment in older patients with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(4):270–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kilari D, Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Mohile SG, et al. Designing exercise clinical trials for older adults with cancer: Recommendations from 2015 Cancer and Aging Research Group NCI U13 Meeting. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(4):293–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Presley CJ, Dotan E, Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, et al. Gaps in nutritional research among older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(4):281–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magnuson A, Allore H, Cohen HJ, et al. Geriatric assessment with management in cancer care: Current evidence and potential mechanisms for future research. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(4):242–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohile SG, Hurria A, Cohen HJ, et al. Improving the quality of survivorship for older adults with cancer. Cancer. 2016;122(16):2459–2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flannery M, Mohile SG, Dale W, et al. Interventions to improve the quality of life and survivorship of older adults with cancer: The funding landscape at NIH, ACS and PCORI. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(4):225–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karuturi M, Wong ML, Hsu T, et al. Understanding cognition in older patients with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(4):258–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]