Abstract

DNA modifications are a major form of epigenetic regulation that eukaryotic cells utilize in concert with histone modifications. While much work has been done elucidating the role of 5-methylcytosine over the past several decades, only recently has it been recognized that N(6)-methyladenine (N6-mA) is present in quantifiable and biologically active levels in the DNA of eukaryotic cells. Unlike prokaryotes which utilize N6-mA to recognize “self” from “foreign” DNA, eukaryotes have been found to use N6-mA in varying ways, from regulating transposable elements to gene regulation in response to hypoxia and stress. In this review, we examine the current state of the N6-mA in research field, and the current understanding of the biochemical mechanisms which deposit and remove N6-mA from the eukaryotic genome.

Keywords: Epigenetics, DNA modification, 6 mA, SMRT, Stress response, Neurogenesis, Cancer

Introduction

One of the mechanisms of epigenetic regulation is that of DNA modification, or the addition of covalent adjuncts to the extant base pairs that make up DNA. The most well-characterized DNA modification in living systems is 5-methylcytosine and its derivatives 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, 5-formylcytosine, and 5-carboxylcytosine (for a review on cytosine methylation see Cedar et al. [1]). Over the past several years, investigation of the modification of adenine in the form of N(6)-methyladenine (N6-mA) has increased due to its discovery in multicellular eukaryotes, specifically mammals, bringing with it a whole possibility of new functions [2–5]. The function of N6-mA in prokaryotes has been widely investigated in the decades since its discovery in bacteria in 1958 [6], where it has been most famously found to play numerous roles in foreign DNA recognition and restriction endonuclease protection [7, 8]. While the function of N6-mA remains to be fully elucidated, recent research into the presence and function of N6-mA, its writers and erasers, has provided several lines of evidence as to its important role in eukaryotic biology.

Discovery and function of N6-mA in prokaryotes

While searching for nucleotide structural analogues in E. coli in 1957, Dunn and Smith measured an abundant level of a novel modified base, N(6)-methyladenine (then named 6-methylaminopurine) [6]. Their subsequent research identified N6-mA in Aerobacter aerogenes, Mycobacterium tuberculosis as well as the bacteriophages T-even and Salmonella bacteriophage in the range of 0.5–2.7% [6]. The levels of N6-mA in the bacteriophages were lower than those of their corresponding bacterial hosts [6]. Further experimentation into the function of N6-mA in prokaryotes found that loss-of-function mutations to the various Dam prokaryotic DNA methyltransferases were not lethal to E. coli; however, the loss of N6-mA methylation did lead to a defective response to λ phage DNA, including a loss of restriction [7]. Investigation into the N6-mA Dam methyltransferase found that it acts upon a specific recognition sequence: 5′-GATC-3′ [9]. The palindromic nature of this sequence allows for methylation of adenine on both strands of the DNA in an equal nature allowing for identification of that DNA as “self” or “foreign” depending on the bacterial species in question and the class of restriction-modification systems utilized by the organism [10]. This sequence is then recognized by methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes which either digest (restrict) the DNA in question (i.e. DpnI) or non-methylated DNA (i.e. DpnII) [11, 12]. Additional functions of N6-mA in prokaryotes include a role in DNA mismatch repair by identification of the original strand [7, 13], regulation of gene expression in hemi/demethylated GATC promotor sites [14, 15], and preventing secondary initiation of genome replication by requiring dual-strand methylation at GATC sites at replication origins [16].

N6-mA in single-celled eukaryotes

While N6-mA was only recently discovered in metazoans, it has been recognized as the primary DNA modification in single-cell protists such as Tetrahymena thermophila and Tetrahymena pyriformis since 1973 [17, 18]. While methylation systems have been studied in great depth within prokaryotes, eukaryotes and metazoans do not contain obvious homologs to Dam methyltransferase or Dpn-like restriction enzymes, indicating that while the modification has the same resultant chemical structure of N(6)-methyladenine, the process by which that methylation occurs and is read is of a different evolutionary origin and serves a discrete function in the context of nucleated cells. As protozoan ciliates, T. thermophila and T. pyriformis exhibit nuclear dimorphism, that is, they contain both a reproductive micronucleus and a somatic macronucleus. The somatic macronucleus is generated by processing a copy of the micronucleus via DNA excision, polyploid replication, and substantial epigenetic modifications [19]. The differences between these nuclei are partially regulated by epigenetic factors including histone modification and DNA methylation, which makes it an important model organism in the investigation of novel epigenetic functions. In the initial papers outlining the presence of N6-mA in T. pyriformis, the authors noted that while N6-mA is present at roughly 0.75% of all adenine sites in the macronucleus, it is all but undetectable in the micronucleus [17]. They also identified that N6-mA in single-celled eukaryotes exists in a motif distinct from that of prokaryotes, with the only identifiable motif being 5′-AT-3′, indicating a Dam-like independent methyltransferase pathway [18]. Subsequent work in Tetrahymena indicated that N6-mA in T. pyriformis and T. thermophila is neither involved in the prokaryotic-like restriction-modification/DNA degradation pathways, nor is it utilized as a mismatch repair process due to its total absence in the micronucleus which is responsible for the reproduction of the organism [17, 20]. More recent research found that N6-mA is enriched at AT sites in the T. thermophila genome, indicating the presence of a methyltransferase due to the significantly increased levels of N6-mA at these sites versus non-AT adenines [20]. This site-specific sequencing was produced via SMRT-seq, which enables nucleotide resolution of DNA modifications (see below) [21]. Luo et al. identified a methyltransferase in T. thermophila they named TAMT-1, a gene containing the MTA70 methyltransferase domain and ZZ-type zinc finger DNA-binding domain [22]. In addition to nucleotide motifs, N6-mA was found to be enriched near nucleosomes containing the histone variant H2A.Z, a transcription-associated histone variant in T. thermophila.

In addition to T. thermophila,N6-mA has been discovered at quantifiable levels (4000 ppm) in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, a green algae [23] and in numerous species of fungi [24]. Within green algae, N6-mA was present at 85% of all genes and was enriched at transcription start sites of genes undergoing transcription indicating a potential activating effect [23]. The deposition of N6-mA at active genes in single-celled eukaryotes is in contrast to the repressive role of N6-mA seen in most mammalian tissues (see below); however, it still unclear whether N6-mA can activate transcription based on recent studies [22]. Thus, further genetic studies are needed for investigate the role of N6-mA in transcription in simple eukaryotes [2, 25, 26].

The search for N6-mA in metazoa

While N6-mA had been identified in prokaryotes and single-celled eukaryotes for several decades, its identification in multicellular eukaryotes and metazoans proved to be a far more difficult task due to the limits of detection in the 1970’s to 80’s which could only detect N6-mA in concentrations > 1:10,000 [27]. The resurgence of metazoan N6-mA research in recent years has primarily been brought about by technological advances in base modification quantification that allows for independent lines of quantitative evidence such as antibody-based quantification (immunoblot), UPLC–MS/MS, and single-molecule real-time sequencing (SMRT-seq). With the maturation of these technologies, N6-mA was found to be present in the germ cells and embryos of D. melanogaster [3] and was discovered in C. elegans [28]. The discovery of N6-mA in D. melanogaster was accompanied by data indicating that the alteration of N6-mA through perturbation of the Drosophila-specific demethylase (DMAD) yielded altered germ cell differentiation [3]. Subsequent publications from other groups have found N6-mA in Mus musculus embryonic stem cells [2], Xenopus laevis testes, M. musculus kidney [29], Danio rerio (zebrafish) embryos [5], Sus domesticus (pig) embryos [5], M. musculus neuronal tissue [30], and H. sapiens glioblastoma [25]. These findings have all been confirmed using immunoblot/immunofluorescence imaging in tandem with UPLC–MS/MS, which reliably detected low-abundance N6-mA (several ppm of total adenines) to relatively high levels (1000 ppm) [25].

The 5-methylcytosine research community has benefited greatly from the comparatively high levels of 5mC found in the mammalian genome and the bisulfite conversion process which allows for base resolution sequencing of 5mC/5hmC deposition using Sanger and next-generation sequencing tools, although it is important to note that bisulfite sequencing cannot distinguish 5hmC from 5mC. No such chemical conversion process exists for N6-mA as of writing, thus studies analyzing the function of N6-mA through site-specific sequencing rely on DNA-immunoprecipitation followed by next-generation sequencing (DIP-seq) or SMRT-seq. The recent development of DIP-seq has significantly increased the resolution and sensitivity of N6-mA mapping [2, 3, 5, 26]. While SMRT-seq, which relies on single-molecule real-time sequencing to identify various DNA modifications via characteristic parameters of the DNA polymerase reaction, is a promising platform to recognize N6-mA at single-nucleotide resolution, it needs to be improved and optimized for recognizing N6-mA in eukaryotic genomes [21]. Current limitations to SMRT-seq include the need for high sequence coverage (25-fold for each strand), and the biologic finding that N6-mA deposition in eukaryotes is often heterogeneous within a cell population (which is in contrast to that of prokaryotes) [21]. Given high N6-mA levels in microorganisms, researchers should consider and rule out contamination as a possible source of N6-mA in their reactions. Sequencing approaches can unbiasedly evaluate the contribution from different genomes, which provides a screening tool to confirm the source of N6-mA peaks. Of note, re-inspection of the non-mammalian contribution in published mammalian datasets is trivial (0.0001–0.5%) [2, 25, 31], in contrast to a recent report [32]. Another concern of possible bias of for simple repeats was raised against DIP-seq including N6-mA and 5mC, which was attributed to non-specificity of IgG for these sequences. However, re-analyses of our published data from murine ESCs and human glioblastoma do not support this claim either [32]. Further improvement in sequencing approaches and bioinformatic analysis are needed for these intriguing yet challenging genomic elements.

Methylation and demethylation machinery in eukaryotes

Identification of N6-mA demethylases in multicellular eukaryotes

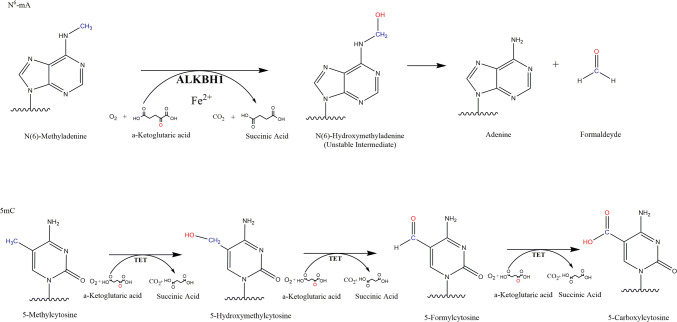

Several recent reports have demonstrated through genetic and in vitro biochemical experimentation that ALKBH1 is a DNA N6-mA demethylase in mammalian cells [2, 25, 31]. ALKBH1 is a homolog of the prokaryotic AlkB α-ketogluterate-dependent dioxygenase which is utilized by prokaryotes to remove DNA adducts that arise by DNA damage, but not N6-mA [33]. AlkB homologs are conserved through the tree of life; metazoans share seven AlkB homologues (ALKBH1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8) and vertebrates have evolved an additional two (ALKBH5 and FTO). AlkB dioxygenase enzymes function by hydroxylating the methyl group of N6-mA, generating an unstable hydroxymethyl group which is spontaneously released as a formaldehyde, resulting in direct demethylation of the base [33–36] (Fig. 1). The N6-mA demethylation process is rapid and complete, requiring only one oxygenation, with no downstream oxygenation products in contrast to the 5mC demethylation pathway in mammals (Fig. 1) [1]. Although N(6)-hydroxymethyladenine (N6-hmA) is chemically unstable, a recent study found its presence in mammalian genomes [37], which indicates that yet unknown protein factors may recognize N6-hmA and thereby potentially prevent it from spontaneous hydrolyzation by storage in a hydrophobic binding pocket [38]. Interestingly, N6-hmA has been reported in RNA as well as an oxidation product of FTO [38]. Thus, although no proteins that bind N6-hmA in DNA or RNA have yet been discovered, unknown pathways may be involved in the regulation of the completion of N6-mA demethylation.

Fig. 1.

N6-mA is demethylated by ALKBH1 by Fe(II)-mediated oxidation using α-ketoglutarate and O2 to oxidize the methyl group. The intermediary N(6)-hydroxymethyladenine is inherently unstable, and rapidly decays to adenine and formaldehyde. 5mC is demethylated after several rounds of TET mediated oxidation followed by base excision repair

The discovery of multiple highly conserved AlkB homologs in multicellular eukaryotes provided in silico evidence that each of the homologs may have a unique catalytic reaction, either in DNA/RNA modification, DNA repair, or other nucleic acid modifications; however, reactions for all nine homologs in vertebrates have not been found [35]. The function of each of these individual enzymes has been studied, but in some cases remains unelucidated (see Table 1 and Fedeles et al. for an in depth review of AlkB homologs [34]). In M. musculus, the perturbation of ALKBH1 by truncation leads to altered placental/fetal development and skews sex ratios in the pups [2, 39, 40]. The authors noted several developmental phenotypes such as reduced birth weight/size, impaired trophoblast lineage differentiation, and eye/craniofacial defects [39]. Along with the discovery of N6-mA in embryonic stem cells in 2016, ALKBH1 was demonstrated to be a strong demethylase of DNA N6-mA in vitro [2] and further experimentation has confirmed that ALKBH1 is a strong demethylase of N6-mA in genomic DNA in both mice and humans [25, 31, 41]. It should be noted that ALKBH1 has been reported to function as a tRNA m1A demethylase, but only in the context of m1A58 in the stem-loop structure; abolishment of the stem-loop structure decreases the affinity of ALKBH1 for m1A [42] or 5mC in mitochondrial tRNA [43]. A recent study also identified ALKBH1 function in regulating N6-mA in mitochondrial DNA, which may explain previous observations of ALKBH1 functions in metabolism [26]. However, it is well known that ALKBH1 is primarily localized to the nucleus in human and mouse embryonic stem cells and neural systems [2, 25, 44]; thus, the physiological significance of ALKBH1 mitochondrial function which was mainly observed in cell culture remains unclear. How DNA N6-mA demethylation activity and tRNA activity contribute to ALKBH1 mitochondrial function has yet to be ascertained. It is also worth noting that ALKBH1 seems to function mainly as a genomic DNA demethylase in cells where ATP production mainly relies on glycolysis and not on mitochondria-based oxidative phosphorylation, such as in embryonic stem cells and cancer cells where ALKBH1 locates to the nucleus, but not mitochondria [44]. Thus, the function of ALKBH1 may be tissue/cell type dependent and further experimentation is needed to determine the pathways that delineate different aspects of ALKBH1 function.

Table 1.

AlkB homologs found in metazoans, their known substrates and known phenotypes on overexpression or depletion

| AlkB homolog | Found in | Substrate | Known phenotypes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkbh1 | Metazoans | DNA N6-mA demethylase, mitochondrial nucleic acid demethylase, putative histone lysine demethylase | Necessary for proper development of M. musculus | [2, 25, 31, 44, 45] |

| Alkbh2 | Metazoans | Nuclear DNA repair enzyme (alkylation damage) | Knockdown impairs rDNA transcription and leads to increased ss/dsDNA breaks | [45–52] |

| Alkbh3 | Metazoans | Nuclear DNA repair enzyme | Necessary for proper recovery from inflammatory response/DNA alkylation | [52–56] |

| Alkbh4 | Metazoans | Actin lysine demethylase | Embryonic lethal, dysregulation of actin/myosin | [57, 58] |

| Alkbh5 | Vertebrates | RNA m6A demethylase | Knockouts have decreased fertility (spermatogenesis-related) | [59–62] |

| Alkbh6 | Metazoans | No available information | No available information | |

| Alkbh7 | Metazoans | Unknown, potentially proteins involved in necrosis | Knockouts have increased obesity | [63–65] |

| Alkbh8 | Metazoans | tRNA maturation (methyltransferase and hydroxylation) | No observable phenotype. Complete loss of uridine modifications upon knockout | [66, 67] |

| FTO | Vertebrates | RNA m6A demethylase, 3-methylthymine/3-methyluracil DNA demethylase. Small nuclear RNA demethylase | Overexpression linked with obesity and diabetes | [60, 68, 69] |

In D. melanogaster, DMAD (originally CG2083), the only αKG-dependent dioxygenase homolog in the Tet/ALKB subfamily, was originally identified as a demethylase of N6-mA in early development, germline cells, and subsequently was confirmed in neurogenesis [3, 70]. Although one study also implicated this protein in demethylating 5mC in RNA, a recent biochemical and genetic study that investigated DMAD function in neurogenesis demonstrated that it serves as a genomic DNA N6-mA demethylase, with minimal/no impact on RNA 5mC levels [70]. Interestingly, the same elegant study of DMAD in neurogenesis also revealed that N6-mA directly recruits the polycomb complex which contributes to PcG/H3K27me-mediated epigenetic silencing in Drosophila, which is in contrast to the proposed activation function in the Drosophila germ line [70]. Consistently, a recent biochemical study demonstrated that N6-mA causes site-specific RNA polymerase pausing [71]. In light of these discoveries, it is of great importance to determine the functional significance of N6-mA depositions at actively transcribed genes in plants, simple eukaryotes and within the Drosophila germline. It will be of great interest to determine the yet unknown mechanisms by which N6-mA has tissue-dependent functions within the same species, such as Drosophila.

Putative N6-mA methyltransferases in eukaryotes

The identification of the predominant DNA N6-mA methyltransferase in eukaryotes is a vital step in both understanding the function of N6-mA in metazoans and obtaining important experimental tools to modulate N6-mA. While the methyltransferase in prokaryotes (Dam) has been known for decades, research into eukaryotic DNA N6-mA methyltransferases has yielded several putative enzymes with no definitive consensus on the primary methyltransferase. Experimental data such as SMRT-seq and N6-mA-IP-seq (DIP-Seq) in eukaryotes have demonstrated a lack of 5′-GATC-3′ motif enrichment, and thus it follows that the primary methyltransferase enzyme in metazoans may be quite different than Dam. The targeted search for active N6-mA methyltransferases in metazoans and mammals has relied on searching for highly conserved motifs and secondary structures found within all methyltransferases which utilize SAM (AdoMet) as a methyl donor in their methyltransferase reactions [72]. As of now, the effort of searching for eukaryotic N6-mA methyltransferases has only generated limited success. These types of screens have yielded the putative N6-mA DNA methyltransferase, TAMT-1 in T. thermophila [31]. Utilizing TAMT-1 knockouts in T. thermophila, Luo et al. found that TAMT-1 is responsible for around 1/3 the N6-mA deposition in the macronucleus [22]. These results coupled with the modest reduction in N6-mA in T. thermophila indicates that while TAMT-1 and its homolog METTL4 may have DNA methyltransferase function, it is likely not the sole DNA N6-mA methyltransferase in single-celled eukaryotes. It is also of interest to determine the role of N6-mA in transcription with TAMT-1 knockouts in future studies. TAMT-1 is a member of the MTA70 family of methyltransferases, and its homologs in C. elegans are DAMT-1 and in humans METTL4 [22]. DAMT-1 is a putative methyltransferase evolved from the MTA-70 family of methyltransferases within C. elegans, and the mutation of specific amino acids in DAMT-1 in catalytic pockets and substrate recognition pockets is able to reduce N6-mA deposition on the C. elegans genome in vivo, whereas the expression of DAMT-1 in SF9 insect cells led to an increase in N6-mA [28]. Researchers have yet been unable to isolate DAMT-1 in cell culture in quantities necessary in vitro to test its N6-mA methylation capacity [28].

A second possible candidate N6-mA DNA methyltransferase is N6AMT-1. A recent study demonstrated in vitro via immunoblot and LC/MS–MS that N6AMT-1 has catalytic activity methylating adenine containing oligos to N6-mA [31]. Additionally, the authors demonstrated via siRNA knockdown that reducing N6AMT-1 reduces N6-mA levels in vitro by roughly 50% in human cancer cell lines or more recently in neurons under stress [30, 31]. However, a previous report using similar biochemical reaction conditions did not observe such activities [73]. The latest attempt to replicate N6AMT-1 activity in vitro or in human glioblastoma cells has also been unsuccessful [25], and additional experimentation and investigation via protein purification and substrate specific assay conditions is called for.

The function of N6-mA in single-celled eukaryotes and invertebrates

In prokaryotes, it has been well established that the role of N6-mA DNA modification is to serve as a signal to identify “self” DNA from “foreign” DNA. N6-mA plays a critical role in the restriction-modification system, and in simple single-celled organisms provides an elegant way to defend against the constant threat of phages and other forms of DNA transfer that would harm the organism. In eukaryotes, especially higher metazoans which contain their own immune system, and thus do not utilize the restriction-modification system of organismal defense, this frees up N6-mA as an additional modification to be used for alternative purposes. Evidence from studies performed in T. thermophila indicates that N6-mA has been adopted as an epigenetic regulator of the macronucleus in several different ways. Recent work has elucidated that N6-mA is anti-correlated with nucleosomes in T. thermophila, indicating an epigenetic effect inverse to that of 5mC in eukaryotes [20, 22]. Indeed, in an entirely in vitro reconstituted experiment using isolated histones and synthesized strands of DNA with a single N6-mA residue, methylation or demethylation of the single residue was able to alter nucleosome positioning indicating a potential function of N6-mA in fine-tuning nucleosome placement in a highly sensitive manner. Experimentation in T. thermophila using high-resolution SMRT-seq identified a significant enrichment of N6-mA in the genic region of the genome, with specific enrichment near the 5′ end of the gene body in actively transcribed genes [20]. It will be of interest to see whether this function is also conversed in metazoans.

Function of N6-mA in mammals

Over the past 3 years, several labs have started exploring the function of N6-mA in eutherians, utilizing mouse and human samples in their studies. Given the novelty of the discovery of N6-mA in eutherians, our knowledge of the function of N6-mA in higher organisms is limited, and we expect greater elucidation into the normal function of N6-mA and its role in disease states over the next decade.

N6-mA in embryonic stem cells

The initial paper discovering the presence of N6-mA in eutherians identified not only the demethylase responsible for demethylation in murine cells, but also a significant repressive effect of N6-mA on its deposition sites within embryonic stem cells, especially on young LINE-1 (long interspersed nuclear element) transposons [2]. Via DIP-seq and SMRT-seq, Wu et al. identified significant enrichment of N6-mA at young and middle-aged LINE-1 transposons [2]. Transposable elements are a class of genetic elements which have (or had) the ability to copy and insert themselves to a new region of the genome utilizing their own sequence [74]. Transposable elements comprise a large portion of the mammalian genome, roughly 50% in mouse and human, and display lower diversity within eutherians than other animals with similarly sized genomes and families [74, 75]. Retrotransposable elements, such as LINE, have retained their ability to insert themselves back into the genome, and in eutherians are thought to be suppressed by epigenetic mechanisms. In embryonic stem cells, however, N6-mA is significantly correlated with epigenetic silencing of LINE-1, but specifically only those with intact reading frames and promotors, in other words elements that pose an active threat to the organism if they reactivate [2]. N6-mA is enriched towards the 5′UTR and ORF1 of LINE1 elements in murine tissues, and studies performed in human tissues have recapitulated this result, reinforcing the hypothesis that N6-mA is a strong transcriptional repression mark in metazons [2, 26].

The examination of N6-mA in single-celled eukaryotes and mammals has identified two functions thus far of N6-mA, as being enriched at transcription start sites and actively transcribed gene bodies mostly in single-celled eukaryotes and the Drosophila germline, and as a repressive mark in eutherians and probably other metazoans [2, 20, 23, 30, 70, 76]. While these roles of N6-mA appear diametrically opposed, the function of epigenetic marks often is often dependent on numerous factors including stage of development, organism, and disease state, thus the role of N6-mA in eukaryotic biology is far from fully elucidated. It is possible that N6-mA has adopted a new, repressive function in metazoans, but several alternative explanations may also exist. Given the difference in genome size between mammals and single-cell eukaryotes, and the sensitivity of the current sequencing techniques which have been used to examine site-specific depositions, it is possible that an enrichment at transcription start sites within actively transcribed genes has escaped observation in multicellular eukaryotes due to low abundance at single-cell level and/or cell-to-cell heterogeneity [71]. Biochemical experiments have identified N6-mA deposition in transcription sites as sufficient to cause RNA PolII pausing/stalling [71], which provides an alternative explanation for the enrichment of N6-mA at actively transcribed genes. Further genetic studies in single-cellular eukaryotes and human/murine cell culture models examining the impact of increased N6-mA methylation on RNA PolII activity will be critical in the synthesis of these discreet findings.

N6-mA has also been found to dynamically alter cell fate decisions during ESC differentiation, one example where the genomic and phenotypic data line up is in placental development. Murine studies using ALKBH1-deficient mice found placental and developmental defects in ALKBH1-knockout mice, and embryonic stem cell ALKBH1-knockout cell lines, which have significantly increased N6-mA deposition, have altered differentiation factor expression including but not limited to CDX2, Lefty1, Foxa2, Gata4 and Gata6 [2, 39, 40]. These data strongly implicate N6-mA as playing a role in regulating embryonic and extraembryonic lineage development and cell potency.

N6-mA as an epigenetic mark in response to stress signals

In addition to its role in downregulating retrotransposon expression in developing stem cells, N6-mA has been found to be enriched in other genes that are downregulated in the mouse, specifically in neuronal tissue of animals undergoing a stress response [30, 76]. While there was no significant overlap between N6-mA deposition and genic regions in murine embryonic stem cells, N6-mA has been found to deposit on genes in the developing brain. Yao et al. examined global dynamic changes to N6-mA deposition in 8-week-old male mice exposed to two hours per day of stress for 14 days, which elicited a chronic stress response in the experimental cohort [30]. Using this technique, they then examined N6-mA levels in various parts of the brain using UHPLC–MS/MS, and found an enrichment of N6-mA over adenine in the pre-frontal cortex of the experimental animals versus the control animals, which was confirmed by dot blot and explored in a site-specific manner via N6-mA-IP-seq [30]. Their initial results confirm the finding that N6-mA is recruited to retrotransposons and intergenic regions. They found that during the stress-response-mediated aberrant methylation LINE sites are significantly downregulated due to N6-mA hypermethylation. Intriguingly they found that the remaining N6-mA enrichment was heavily deposited in intragenic sites (33%) versus exons (0.3%) [30]. Yao et al. found a large number of differentially methylated sites but determined that hypomethylated sites are located at the TSS and TES, whereas hypermethylated sites are located in the gene body between those sites. They additionally determined that N6-mA deposition is enriched at genes associated with psychiatric disease-correlated loci (depression, schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder) which indicates that N6-mA plays a critical role in epigenetic silencing in the pre-frontal cortex’s stress response pathway [30]. These were some of the first data in eutherians to indicate that N6-mA plays a directed epigenetic role in stimuli response, and since then this pattern has been seen in neoplasms as well as healthy tissues.

N6-mA in human tumors

While Yao et al. examined stressed but otherwise healthy neuronal tissue in a murine model, recent studies from the Xiao and Rich labs examined the role of both N6-mA and ALKBH1 in the cellular processes and prognosis for adult human patients with glioblastoma [25]. Glioblastomas are highly invasive neoplasms that drive from glial tissue in the brain, where alterations to global and gene-specific levels of DNA modifications such as 5mC and 5hmC have been previously observed. Xie et al. found that N6-mA is dramatically (500-fold) upregulated in glioma stem cell lines (cells that can give rise to remote neoplasms in a mouse model) in vitro and in primary glioblastoma cells directly from patients. These findings were relatively uniform across samples from 67 patients, indicating a substantial aberrant regulation of N6-mA during the carcinogenesis and proliferative phase of the cancer. Xie et al. also interrogated pathways regulated by ALKBH1 in human glioblastoma cells by knocking down ALKBH1 and discovered a significant enrichment of N6-mA near key oncogenic pathways characterized in glioblastoma carcinogenesis, including hypoxia response pathways. Glioblastoma is a fast-growing tumor that struggles to maintain adequate vascularization to the entire tumor, leading to hypoxic necrosis of the core of the tumor. Upregulation of genes that help a cell adjust to these hypoxic environments are a hallmark of glioma stem cells [25]. Previous research had investigated the role of chromatin modification in the form of histone modifications and had linked histone modification H3K9me3 with the repression of hypoxia-induced genes; in their analysis of N6-mA deposition sites, Xie et al. found that 83% of genes associated with H3K9me3 hypoxia-induced sites had an increase in N6-mA after ALKBH1 knockout [25]. These data indicate that in the case of glioblastoma, the cancer cells have may have co-opted N6-mA as a regulatory marker and use ALKBH1 to upregulate the expression of hypoxia-induced genes, allowing them to proliferate in the severely hypoxic conditions within the tumor. These findings coupled with the relative lack of N6-mA signaling in a majority of sampled tissues [2, 27, 29] indicate that the N6-mA regulatory network may be an ideal therapeutic target for glioblastoma and other cancers with aberrant N6-mA/ALKBH1/N6-mA methyltransferase activity [25]. While this work provides novel insights into the potential function of N6-mA in cancers, further research is necessary to confirm these results in other tumor types and patient cohorts.

While the discovery of N(6)-methyladenine dates back to 1957, our understanding of this necessary DNA modification in eukaryotes is in its infancy in comparison to other DNA modifications such as 5mC and its derivatives. In general, N6-mA in mammalian genomes seems to be sensitive to various environmental signals, such as fear conditioning and hypoxia, which indicate that this modification may quickly respond to environmental cues and plays vital regulatory functions. For example, a study reported that when ES cells are cultured under chemical inhibitors against MAPK and GSK3B, N6-mA cannot be easily detected, in contrast to the standard serum/LIF medium [77, 78]. This condition, which is often referred as “2i”, greatly compromises ESC pluripotency when used in long-term culture and triggers global DNA and histone demethylation [78, 79]. This example underscores the importance of understanding the regulatory pathways of N6-mA and complexity of mammalian epigenetic regulation.

Future perspectives

N6-mA has emerged as a potent regulator of gene expression, chromatin configuration, stem cell potency, stress response, tumorigenesis, and retrotransposon suppression. With renewed interest in this field, our understanding of the role N6-mA plays in metazoan and eutherian biology grows weekly providing us new answers in the field of epigenetics and opening new avenues of scientific inquiry with the promise of potential therapeutic interventions. The research performed into the existence and function of N6-mA in eukaryotes is in its early stages, and additional research into the machineries involved as writers (methyltransferases), readers (binding proteins), and erasers (demethylases) of N6-mA is necessary to further our knowledge of the function N6-mA. One major challenge of N6-mA research is its low abundance in a population of cells. Immunofluorescence and SMRT-seq studies implicated cell-to-cell heterogeneity as a contributing factor and, therefore, developing novel approach for enriching the N6-mA presenting subpopulation would greatly facilitate this line of investigation. Another key hurdle to investigating N6-mA is the difficulty in quantifying and mapping N6-mA deposition in low numbers of cells. We encourage research into enhancing the specificity of existing tools such as SMRT-seq and DIP-seq, as these technical limitations currently limit research to samples with abundant levels of N6-mA or large numbers of cells.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cedar H, Bergman Y. Programming of DNA methylation patterns. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:97–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052610-091920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu TP, Wang T, Seetin MG, Lai Y, Zhu S, Lin K, et al. DNA methylation on N(6)-adenine in mammalian embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2016;532(7599):329–333. doi: 10.1038/nature17640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang G, Huang H, Liu D, Cheng Y, Liu X, Zhang W, et al. N6-methyladenine DNA modification in Drosophila. Cell. 2015;161(4):893–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo GZ, Blanco MA, Greer EL, He C, Shi Y. DNA N(6)-methyladenine: a new epigenetic mark in eukaryotes? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16(12):705–710. doi: 10.1038/nrm4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu J, Zhu Y, Luo GZ, Wang X, Yue Y, Wang X, et al. Abundant DNA 6 mA methylation during early embryogenesis of zebrafish and pig. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13052. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunn DB, Smith JD. The occurrence of 6-methylaminopurine in deoxyribonucleic acids. Biochem J. 1958;68(4):627–636. doi: 10.1042/bj0680627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marinus MG, Morris NR. Isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid methylase mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1973;114(3):1143–1150. doi: 10.1128/jb.114.3.1143-1150.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marinus MG, Lobner-Olesen A (2014) DNA methylation. EcoSal Plus 6(1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Geier GE, Modrich P. Recognition sequence of the dam methylase of Escherichia coli K12 and mode of cleavage of Dpn I endonuclease. J Biol Chem. 1979;254(4):1408–1413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bickle TA, Kruger DH. Biology of DNA restriction. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57(2):434–450. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.2.434-450.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vovis GF, Lacks S. Complementary action of restriction enzymes endo R-DpnI and Endo R-DpnII on bacteriophage f1 DNA. J Mol Biol. 1977;115(3):525–538. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacks S, Greenberg B. A deoxyribonuclease of Diplococcus pneumoniae specific for methylated DNA. J Biol Chem. 1975;250(11):4060–4066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kramer B, Kramer W, Fritz HJ. Different base/base mismatches are corrected with different efficiencies by the methyl-directed DNA mismatch-repair system of E. coli. Cell. 1984;38(3):879–887. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sternberg N. Evidence that adenine methylation influences DNA-protein interactions in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;164(1):490–493. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.1.490-493.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robbins-Manke JL, Zdraveski ZZ, Marinus M, Essigmann JM. Analysis of global gene expression and double-strand-break formation in DNA adenine methyltransferase- and mismatch repair-deficient Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(20):7027–7037. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.20.7027-7037.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu M, Campbell JL, Boye E, Kleckner N. SeqA: a negative modulator of replication initiation in E. coli. Cell. 1994;77(3):413–426. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorovsky MA, Hattman S, Pleger GL. (6 N)methyl adenine in the nuclear DNA of a eucaryote, Tetrahymena pyriformis. J Cell Biol. 1973;56(3):697–701. doi: 10.1083/jcb.56.3.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blackburn EH, Pan WC, Johnson CC. Methylation of ribosomal RNA genes in the macronucleus of Tetrahymena thermophila. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11(15):5131–5145. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.15.5131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chalker DL, Meyer E, Mochizuki K. Epigenetics of ciliates. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(12):a017764. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a017764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Chen X, Sheng Y, Liu Y, Gao S. N6-adenine DNA methylation is associated with the linker DNA of H2A.Z-containing well-positioned nucleosomes in Pol II-transcribed genes in Tetrahymena. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(20):11594–11606. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu S, Beaulaurier J, Deikus G, Wu TP, Strahl M, Hao Z, et al. Mapping and characterizing N6-methyladenine in eukaryotic genomes using single-molecule real-time sequencing. Genome Res. 2018;28(7):1067–1078. doi: 10.1101/gr.231068.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo GZ, Hao Z, Luo L, Shen M, Sparvoli D, Zheng Y, et al. N(6)-methyldeoxyadenosine directs nucleosome positioning in Tetrahymena DNA. Genome Biol. 2018;19(1):200. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1573-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu Y, Luo GZ, Chen K, Deng X, Yu M, Han D, et al. N6-methyldeoxyadenosine marks active transcription start sites in Chlamydomonas. Cell. 2015;161(4):879–892. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mondo SJ, Dannebaum RO, Kuo RC, Louie KB, Bewick AJ, LaButti K, et al. Widespread adenine N6-methylation of active genes in fungi. Nat Genet. 2017;49(6):964–968. doi: 10.1038/ng.3859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie Q, Wu TP, Gimple RC, Li Z, Prager BC, Wu Q, et al. N(6)-methyladenine DNA modification in glioblastoma. Cell. 2018;175(5):1228–43 e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koh CWQ, Goh YT, Toh JDW, Neo SP, Ng SB, Gunaratne J, et al. Single-nucleotide-resolution sequencing of human N6-methyldeoxyadenosine reveals strand-asymmetric clusters associated with SSBP1 on the mitochondrial genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(22):11659–11670. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vanyushin BF, Tkacheva SG, Belozersky AN. Rare bases in animal DNA. Nature. 1970;225(5236):948–949. doi: 10.1038/225948a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greer EL, Blanco MA, Gu L, Sendinc E, Liu J, Aristizabal-Corrales D, et al. DNA methylation on N6-adenine in C. elegans. Cell. 2015;161(4):868–878. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koziol MJ, Bradshaw CR, Allen GE, Costa ASH, Frezza C, Gurdon JB. Identification of methylated deoxyadenosines in vertebrates reveals diversity in DNA modifications. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23(1):24–30. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yao B, Cheng Y, Wang Z, Li Y, Chen L, Huang L, et al. DNA N6-methyladenine is dynamically regulated in the mouse brain following environmental stress. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1122. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01195-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao CL, Zhu S, He M, Chen D, Zhang Q, Chen Y, et al. N(6)-methyladenine DNA modification in the human genome. Mol Cell. 2018;71(2):306–18 e7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lentini A, Lagerwall C, Vikingsson S, Mjoseng HK, Douvlataniotis K, Vogt H, et al. A reassessment of DNA-immunoprecipitation-based genomic profiling. Nat Methods. 2018;15(7):499–504. doi: 10.1038/s41592-018-0038-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen L, Song CX, He C, Zhang Y. Mechanism and function of oxidative reversal of DNA and RNA methylation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2014;83(1):585–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060713-035513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fedeles BI, Singh V, Delaney JC, Li D, Essigmann JM. The AlkB family of Fe(II)/alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases: repairing nucleic acid alkylation damage and beyond. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(34):20734–20742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.656462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aravind L, Koonin EV. The DNA-repair protein AlkB, EGL-9, and leprecan define new families of 2-oxoglutarate- and iron-dependent dioxygenases. Genome Biol. 2001;2(3):RESEARCH0007. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-3-research0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Falnes PO, Rognes T. DNA repair by bacterial AlkB proteins. Res Microbiol. 2003;154(8):531–538. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(03)00150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiong J, Ye TT, Ma CJ, Cheng QY, Yuan BF, Feng YQ. N6-Hydroxymethyladenine: a hydroxylation derivative of N6-methyladenine in genomic DNA of mammals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;47:1268–1277. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fu Y, Jia G, Pang X, Wang RN, Wang X, Li CJ, et al. FTO-mediated formation of N6-hydroxymethyladenosine and N6-formyladenosine in mammalian RNA. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1798. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nordstrand LM, Svard J, Larsen E, Nilsen A, Ougland R, Furu K, et al. Mice lacking Alkbh1 display sex-ratio distortion and unilateral eye defects. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(11):e13827. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pan Z, Sikandar S, Witherspoon M, Dizon D, Nguyen T, Benirschke K, et al. Impaired placental trophoblast lineage differentiation in Alkbh1(−/−) mice. Dev Dyn. 2008;237(2):316–327. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou C, Liu Y, Li X, Zou J, Zou S. DNA N(6)-methyladenine demethylase ALKBH1 enhances osteogenic differentiation of human MSCs. Bone Res. 2016;4:16033. doi: 10.1038/boneres.2016.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu F, Clark W, Luo G, Wang X, Fu Y, Wei J, et al. ALKBH1-mediated tRNA demethylation regulates translation. Cell. 2016;167(3):816–28 e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawarada L, Suzuki T, Ohira T, Hirata S, Miyauchi K, Suzuki T. ALKBH1 is an RNA dioxygenase responsible for cytoplasmic and mitochondrial tRNA modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(12):7401–7415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ougland R, Lando D, Jonson I, Dahl JA, Moen MN, Nordstrand LM, et al. ALKBH1 is a histone H2A dioxygenase involved in neural differentiation. Stem Cells. 2012;30(12):2672–2682. doi: 10.1002/stem.1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Westbye MP, Feyzi E, Aas PA, Vagbo CB, Talstad VA, Kavli B, et al. Human AlkB homolog 1 is a mitochondrial protein that demethylates 3-methylcytosine in DNA and RNA. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(36):25046–25056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803776200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li P, Gao S, Wang L, Yu F, Li J, Wang C, et al. ABH2 couples regulation of ribosomal DNA transcription with DNA alkylation repair. Cell Rep. 2013;4(4):817–829. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu C, Yi C. Switching demethylation activities between AlkB family RNA/DNA demethylases through exchange of active-site residues. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53(14):3659–3662. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen B, Liu H, Sun X, Yang CG. Mechanistic insight into the recognition of single-stranded and double-stranded DNA substrates by ABH2 and ABH3. Mol BioSyst. 2010;6(11):2143–2149. doi: 10.1039/c005148a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fu D, Samson LD. Direct repair of 3, N(4)-ethenocytosine by the human ALKBH2 dioxygenase is blocked by the AAG/MPG glycosylase. DNA Repair (Amst) 2012;11(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nay SL, Lee DH, Bates SE, O’Connor TR. Alkbh2 protects against lethality and mutation in primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts. DNA Repair (Amst) 2012;11(5):502–510. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cetica V, Genitori L, Giunti L, Sanzo M, Bernini G, Massimino M, et al. Pediatric brain tumors: mutations of two dioxygenases (hABH2 and hABH3) that directly repair alkylation damage. J Neurooncol. 2009;94(2):195–201. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9837-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duncan T, Trewick SC, Koivisto P, Bates PA, Lindahl T, Sedgwick B. Reversal of DNA alkylation damage by two human dioxygenases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(26):16660–16665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262589799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dango S, Mosammaparast N, Sowa ME, Xiong LJ, Wu F, Park K, et al. DNA unwinding by ASCC3 helicase is coupled to ALKBH3-dependent DNA alkylation repair and cancer cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2011;44(3):373–384. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koike K, Ueda Y, Hase H, Kitae K, Fusamae Y, Masai S, et al. anti-tumor effect of AlkB homolog 3 knockdown in hormone- independent prostate cancer cells. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2012;12(7):847–856. doi: 10.2174/156800912802429283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Calvo JA, Meira LB, Lee CY, Moroski-Erkul CA, Abolhassani N, Taghizadeh K, et al. DNA repair is indispensable for survival after acute inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(7):2680–2689. doi: 10.1172/JCI63338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sundheim O, Vagbo CB, Bjoras M, Sousa MM, Talstad V, Aas PA, et al. Human ABH3 structure and key residues for oxidative demethylation to reverse DNA/RNA damage. EMBO J. 2006;25(14):3389–3397. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bjornstad LG, Zoppellaro G, Tomter AB, Falnes PO, Andersson KK. Spectroscopic and magnetic studies of wild-type and mutant forms of the Fe(II)- and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent decarboxylase ALKBH4. Biochem J. 2011;434(3):391–398. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li MM, Nilsen A, Shi Y, Fusser M, Ding YH, Fu Y, et al. ALKBH4-dependent demethylation of actin regulates actomyosin dynamics. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1832. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feng C, Liu Y, Wang G, Deng Z, Zhang Q, Wu W, et al. Crystal structures of the human RNA demethylase Alkbh5 reveal basis for substrate recognition. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(17):11571–11583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.546168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shen F, Huang W, Huang JT, Xiong J, Yang Y, Wu K, et al. Decreased N(6)-methyladenosine in peripheral blood RNA from diabetic patients is associated with FTO expression rather than ALKBH5. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(1):E148–E154. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thalhammer A, Bencokova Z, Poole R, Loenarz C, Adam J, O’Flaherty L, et al. Human AlkB homologue 5 is a nuclear 2-oxoglutarate dependent oxygenase and a direct target of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) PLoS ONE. 2011;6(1):e16210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, Fedorcsak P, Huang CM, Li CJ, et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell. 2013;49(1):18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fu D, Jordan JJ, Samson LD. Human ALKBH7 is required for alkylation and oxidation-induced programmed necrosis. Genes Dev. 2013;27(10):1089–1100. doi: 10.1101/gad.215533.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Solberg A, Robertson AB, Aronsen JM, Rognmo O, Sjaastad I, Wisloff U, et al. Deletion of mouse Alkbh7 leads to obesity. J Mol Cell Biol. 2013;5(3):194–203. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjt012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang G, He Q, Feng C, Liu Y, Deng Z, Qi X, et al. The atomic resolution structure of human AlkB homolog 7 (ALKBH7), a key protein for programmed necrosis and fat metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(40):27924–27936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.590505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van den Born E, Vagbo CB, Songe-Moller L, Leihne V, Lien GF, Leszczynska G, et al. ALKBH8-mediated formation of a novel diastereomeric pair of wobble nucleosides in mammalian tRNA. Nat Commun. 2011;2:172. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pastore C, Topalidou I, Forouhar F, Yan AC, Levy M, Hunt JF. Crystal structure and RNA binding properties of the RNA recognition motif (RRM) and AlkB domains in human AlkB homolog 8 (ABH8), an enzyme catalyzing tRNA hypermodification. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(3):2130–2143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.286187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jia G, Yang CG, Yang S, Jian X, Yi C, Zhou Z, et al. Oxidative demethylation of 3-methylthymine and 3-methyluracil in single-stranded DNA and RNA by mouse and human FTO. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(23–24):3313–3319. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mauer J, Sindelar M, Despic V, Guez T, Hawley BR, Vasseur JJ, et al. FTO controls reversible m(6)Am RNA methylation during snRNA biogenesis. Nat Chem Biol. 2019;15(4):340–347. doi: 10.1038/s41589-019-0231-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yao B, Li Y, Wang Z, Chen L, Poidevin M, Zhang C, et al. Active N(6)-methyladenine demethylation by DMAD regulates gene expression by coordinating with polycomb protein in neurons. Mol Cell. 2018;71(5):848–57 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang W, Xu L, Hu L, Chong J, He C, Wang D. Epigenetic DNA modification N(6)-methyladenine causes site-specific RNA polymerase II transcriptional pausing. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139(41):14436–14442. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b06381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Timinskas A, Butkus V, Janulaitis A. Sequence motifs characteristic for DNA [cytosine-N4] and DNA [adenine-N6] methyltransferases. Classification of all DNA methyltransferases. Gene. 1995;157(1–2):3–11. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00783-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu P, Nie S, Li B, Yang ZQ, Xu ZM, Fei J, et al. Deficiency in a glutamine-specific methyltransferase for release factor causes mouse embryonic lethality. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(17):4245–4253. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00218-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sotero-Caio CG, Platt RN, 2nd, Suh A, Ray DA. Evolution and diversity of transposable elements in vertebrate genomes. Genome Biol Evol. 2017;9(1):161–177. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goodier JL, Kazazian HH., Jr Retrotransposons revisited: the restraint and rehabilitation of parasites. Cell. 2008;135(1):23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kigar SL, Chang L, Guerrero CR, Sehring JR, Cuarenta A, Parker LL, et al. N(6)-methyladenine is an epigenetic marker of mammalian early life stress. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):18078. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18414-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schiffers S, Ebert C, Rahimoff R, Kosmatchev O, Steinbacher J, Bohne AV, et al. Quantitative LC-MS provides no evidence for m(6) dA or m(4) dC in the genome of mouse embryonic stem cells and tissues. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2017;56(37):11268–11271. doi: 10.1002/anie.201700424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Choi J, Huebner AJ, Clement K, Walsh RM, Savol A, Lin K, et al. Prolonged Mek1/2 suppression impairs the developmental potential of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2017;548(7666):219–223. doi: 10.1038/nature23274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Carey BW, Finley LW, Cross JR, Allis CD, Thompson CB. Intracellular alpha-ketoglutarate maintains the pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2015;518(7539):413–416. doi: 10.1038/nature13981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]