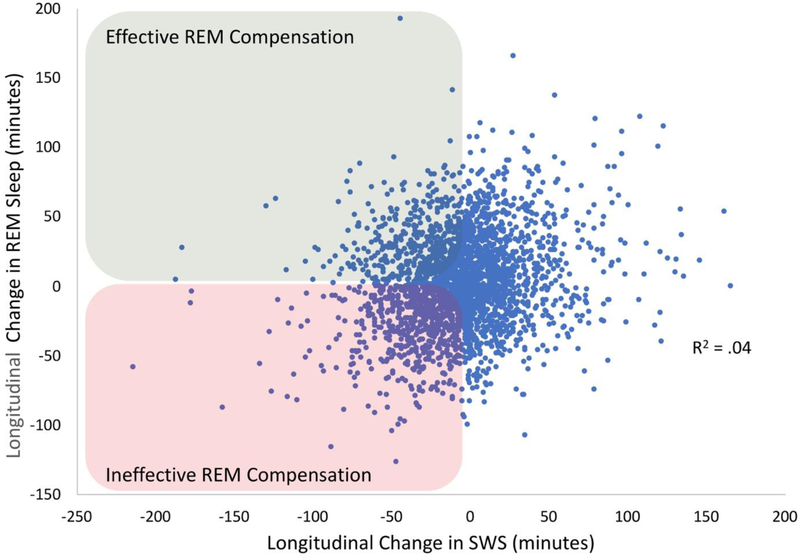

Figure 2. Novel Analyses of the Changes in SWS and REM Sleep in the Sleep Heart Health Study.

Difference scores represent how much SWS and REM sleep were lost over approximately 5 years, with the correlation of loss being significant, but modest in size (r = .20, p < .001, R2 = .04). The effect size remained the same (r = .20) when controlling for chronological age. Highlighted in green are individuals whose SWS declined, but who showed an increase in REM sleep, which we theorize reflects compensation and should promote cognitive preservation. Highlighted in red are individuals who showed declining SWS, without any REM compensation, which we theorize should lead to cognitive decline and dementia. Increased SWS in the presence of increased/decreased REM is likely also relevant, and perhaps reflecting increases/decreases in exercise, diet, social/cognitive engagement, or other resiliency factors [79].