Abstract

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disorder with no known cure and with an average life expectancy of 3–5 years post diagnosis. The use of complementary medicine such as medicinal cannabis in search for a potential treatment or cure is common in ALS. Preclinical studies have demonstrated the efficacy of cannabinoids in extending the survival and slowing of disease progression in animal models with ALS. There are anecdotal reports of cannabis slowing disease progression in persons with ALS (pALS) and that cannabis alleviated the symptoms of spasticity and pain. However, a clinical trial in pALS with these objectives has not been conducted.

Methods and analysis

The Efficacy of cannabis-based Medicine Extract in slowing the disease pRogression of Amyotrophic Lateral sclerosis or motor neurone Disease trial is a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled cannabis trial in pALS conducted at the Gold Coast University Hospital, Australia. The investigational product will be a cannabis-based medicine extract (CBME) supplied by CannTrust Inc., Canada, with a high-cannabidiol-low-tetrahydrocannabinol concentration. A total of 30 pALS with probable or definite ALS diagnosis based on the El Escorial criteria, with a symptom duration of <2 years, age between 25 and 75

years and with at least 70% forced vital capacity (FVC) will be treated for 6 months. The primary objective of the study is to evaluate the efficacy of CBME compared with placebo in slowing the disease progression measured by differences in mean ALS Functional Rating Scale-Revised and FVC score between the groups at the end of treatment. The secondary objectives are to evaluate the safety and tolerability of CBME by summarising adverse events, the effects of CBME on spasticity, pain, weight loss and quality of life assessed by the differences in mean Numeric Rating Scale for spasticity and Numeric Rating Scale for pain, percentage of total weight loss and ALS specific quality of life-Revised questionnaire.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been approved by the local Institutional Review Board. The results of this study will be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

Keywords: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, motor neurone disease, cannabis, clinical trials, cannabinoid

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will evaluate the efficacy of cannabis in slowing amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neurone disease (ALS/MND) progression.

This study will also evaluate the efficacy of cannabis in improving the quality of life and in managing ALS/MND-associated symptoms such as pain, spasticity and weight loss.

This study is limited by not using a biomarker.

This study has limitations in generalisibility as it only focuses on enrolling early-stage ALS/MND patients, i.e.ie, <2 years of symptom onset.

Background

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as motor neuron disease (MND), is a fatal neuromuscular disorder that results in the degeneration of the motor neurons in the cortex, brain stem and spinal cord.1 2 It is characterised by progressive weakness and wasting of skeletal muscles and loss of the ability to swallow or speak.2 It commonly affects patients between 50 and 65 years of age.2–4 The aetiology of ALS is largely unknown, although there is robust evidence demonstrating genetic or inherited causes accounting for 5% to 10% of the ALS population.5 The average life expectancy from diagnosis is 3–5 years, but a small percentage of persons with ALS (pALS) may survive longer.2 3

More than 30 gene mutations have been linked to ALS such as SOD1, TARDBP (TDP-43), FUS/TLS and C9orf72.5 Despite these advances, the pathophysiology of sporadic ALS remains unknown. Theories proposed include reduced glutamate uptake resulting in excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, neuroinflammation and dysregulation of cellular metabolism.6

The activation of the endocannabinoid system (ECS) has been demonstrated to reduce excitotoxicity, oxidative cell damage and neuroinflammation.7 8 ECS is a vital physiological neuromodulatory system in human beings; it is involved in regulating homeostasis. ECS is widely expressed in different parts of the human body, particularly in the brain and spinal cord. ECS regulates physiological processes such as pain, emotions, stress, neural development, inflammation, appetite and sleep cycles.9 ECS has two major cannabinoid (CB) receptors - CB1 and CB2. CB1 receptors are extremely abundant in the nervous system while CB2 receptors are more present in immune cells.10

Endogenous CBs (CBs that are intrinsic to humans) activate the ECS and have important roles in the naturalistic defence of the nervous system.11 Anadamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol, known as endocannabinoids, are presumed to have key roles in slowing ALS progression. Endocannabinoids accumulated in the spinal cord of ALS mice with SOD1 mutations12 13 and acted as protective responses when the disease was progressing. It is therefore proposed that by introducing exogenous CBs such as delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and/or cannabidiol (CBD), there is a possibility of slowing ALS progression.

Preclinical studies have explored the relationship between ECS and ALS progression using transgenic mice with SOD1 and TDP-43 mutations.12 14–17 The administration of THC, an exogenous endocannabinoid that partially activates CB1 receptors18 in transgenic SOD1 mice (either before or during the onset of symptoms) reduced motor impairment by 6% and extended survival by 5%.15 Similarly, the administration of WIN55,212–2 (a CB1/CB2 receptor agonist) in transgenic SOD1 mice after symptom onset significantly slowed disease progression.12 The genetic ablation of fatty acid amide hydrolase enzymes, which eventually increases endocannabinoid levels, also slowed disease progression and ameliorated disease signs.12

Activating CB2 receptors is also believed to slow ALS progression.11 CB2 receptors block beta-amyloid- induced microglial activation which mediates excitotoxicity and neuronal damage.19 To further support this claim, AM1241 (a selective CB2 receptor agonist) was administered to transgenic SOD1 mice after disease onset and demonstrated significant slowing of the disease.14 Also, the administration of AM1241 3 mg/kg produced a 56% increase in survival interval and 11% increase in lifespan of SOD1 mice.16

CB2 receptors also regulate the human immune system. Neuroinflammation is proposed as a possible mechanism in pathophysiology of ALS; hence, regulating the immune system to counteract inflammation via CB2 receptors may positively modify disease progression.20 The relationship of ECS in TDP-43, one of the genetic mutations causing ALS and frontotemporal dementia has been investigated.21 Upregulation of CB2 receptors in the spinal cord of TDP-43 mice was demonstrated. This supports the premise that CB2 receptors are involved in the ALS pathogenesis, possibly as endogenous protective response.

There are case studies and anecdotal reports indicating improvement of symptoms in patients with confirmed ALS by using cannabis.20 In a survey of pALS, respondents admitted that cannabis moderately reduced disease-associated symptoms such as appetite loss, depression, pain, spasticity and drooling.22

Human clinical trials have investigated CBs in pALS. However, these trials mainly focused on symptom management rather than disease modification. One study showed symptomatic benefits in areas of sleep, appetite and spasticity.23 It also demonstrated the safety of using THC in pALS. Another clinical trial explored the effects of THC (Marinol) in ALS patients with cramps,24 but the differences seen were not statistically significant. The authors pointed out that their results might be negative due to the small THC (Marinol) doses used and the short treatment period (2 weeks), making them too small/short for significant changes to show up.24 A more recent clinical trial has demonstrated significant reduction of ALS-related spasticity with 25CBs and a larger clinical trial is underway.

CBs are largely regarded as safe for the ALS population.23–25 Given the potential therapeutic benefits, further investigation is warranted. The most logical next step is to conduct a human clinical trial.26 This study was designed to explore the efficacy of cannabis-based medicine extract (CBME) in slowing ALS progression and improving symptom control.

Methods and analysis

Study overview

The Efficacy of cannabis-based Medicine Extract in slowing the disease pRogression of Amyotrophic Lateral sclerosis or motor neurone Disease (EMERALD) trial is a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled single centre study enrolling ALS patients with symptom onset within the last 2 years prior to randomisation. Patient recruitment will take place at Gold Coast University Hospital (GCUH), Australia. Recruitment of participants started in January 2019. All participants will be screened and if eligible will be enrolled in the trial. All participants are required to give written, informed consent prior to enrolment. Participants will take either the study drug or placebo for 6 months. They will be followed up by face-to-face visits 3 monthly and via phone call every month. It is anticipated that the study will take 2.5 years to complete (January 2019 to June 2021).

Study objectives

The primary objective of the EMERALD trial is to evaluate the efficacy of CBME in slowing the disease progression in patients with ALS over 6 months of treatment using the ALS Functional Rating Scale-Revised (ALSFRS-R) and forced vital capacity (FVC).

The secondary objectives are to evaluate the safety and tolerability of CBME, its effects on spasticity, pain, weight loss and quality of life. Safety and tolerability will be assessed by collecting the number of adverse events, spasticity and pain scores using the Numeric Rating Scale for spasticity and Numeric Rating Scale for pain, weight loss by calculating the percentage of total weight loss and the quality of life using the ALS specific quality of life-Revised questionnaire.

This study will also explore the effects of CBME in cognition and behaviour of patients using the Edinburgh Cognitive and behavioural ALS Screen (ECAS). As an additional safety measure, risk of suicide will be assessed for all patients using the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale.

Additional clinical endpoints include death and inability to swallow.

Study population

All consecutive patients that attend or are referred to GCUH neurology ALS/MND clinic with ALS/MND diagnosis and symptom onset within the last 2 years, aged between 25 and 75 and recent FVC of at least 70% will be screened for eligibility. The age range (25–75 years) was chosen because cannabis use may cause memory deficits in the developing brain (up to 24 years old)27 28 and there is limited data on the safety of cannabis in the elderly. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarised in Box 1.

Box 1. The Efficacy of cannabis-based Medicine Extract in slowing the disease pRogression of Amyotrophic Lateral sclerosis or motor neurone Disease trial inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neurone disease, either definite or probable, according to the El Escorial revised criteria.

Male or female patient, 25–75 years old.

Onset of first symptom within the last 2 years.

Forced vital capacity of at least 70% on baseline.

Exclusion criteria

Participants who are bedridden.

Have used or taken cannabis or cannabinoid-based medications within 30 days of study entry.

History of any psychiatric disorder other than depression associated with their underlying condition. including immediate family history of schizophrenia.

Any of the following: estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate <30 mL/min/1.73m2, ejection fraction <35%, or Aspartate Aminotransferase and Alanine Aminotransferase>5 X Upper Limit Normal.

Pregnant, lactating mothers or female participants planning pregnancy during the study and for 30 days thereafter.

Unwilling to stop driving and operate heavy machineries.

Prior randomisation, the study team will ask each patient if they have taken cannabis or CBME within the last 30 days. Additionally, each patient will undergo a THC urine test prior randomisation. Patients who test positive for THC will be excluded.

Study intervention

Investigational product

The investigational product is CBD oil formulated as a capsule and is supplied by CannTrust Inc., Canada. CannTrust Inc. is a licensed producer of medical grade cannabis. The investigational product contains 25 mg of CBD and <2 mg of THC (+/-10%). Identical placebo capsules will contain only medium chain triglyceride oil, which is the carrier for the study drug. There will be no CBs or other cannabis-based compounds in the placebo.

A systematic review of CBs in ALS-murine models29 demonstrated the efficacy of CBs in prolonging survival of SOD1-G93A mice. A high-CBD-low-THC formulation was chosen because this most closely resembles the preparation used in an animal model study30 which demonstrated prolonged survival.

Additionally, the rationale for choosing a high-CBD-low-THC formulation relates to the entourage effect of CB. When administered together, the CB modulate or enhance the effects of the various components, and the reduction of psychoactive effects associated with cannabis can be seen.31 THC and CBD are two well-understood CBs of the 60 constituents of the cannabis plant.32 THC is the major psychoactive constituent in cannabis, while CBD is known to have neuroprotective effects and is non-intoxicating, but has antianxiety and antipsychotic activity. CBD modulates the activation of CB receptors31 and may counteract the psychoactive effects of THC.33 A high-CBD-low-THC ratio was chosen for this study not only to mitigate the psychoactive effects of THC but to leverage the neuroprotective potential of CBD.

Dose and mode of administration

The maximum dose was determined by balancing the expected dose range for therapeutic effects with doses associated with undesired side effects. The CBD oil to be used in this study comprises CBD and THC in the ratio 25:<2, where the THC component is known to be the agent causing potential psychoactive side effects. The therapeutic range of CBD/THC products (for social anxiety disorder, epilepsy and insomnia) was found to be 150–600 mg of CBD/day.34 This equates to <12 mg to <48 mg of THC of the study drug. However, as little as 2.5–3.0 mg of pure THC in a single bolus has been reported to cause psychoactive effects in cannabis naïve patients.35 We expect we will be able to avoid low-dose THC psychoactive side effects as (1) THC is combined with CBD which is known to mitigate the psychoactive effects of THC36 and (2) the daily dose will be given two or three times a day (split between two doses 8–12 hours apart). In addition, we will employ the ‘start low and go slow’ rationale to increase the dose into the likely therapeutic range, thus allowing for adaptation by patients to potential side effects. The Clinical Guidance for the use of medicinal cannabis products in Queensland35, where this trial is being conducted, suggests a maximum dose of 32.4 mg/day of THC for Sativex and 40 mg of THC for Marinol. The investigators set <30 mg of THC as the maximum dose for our trial. This is a conservative maximum dose but is still expected to produce therapeutic results.

The medication is to be taken orally daily for 6 months. The appropriate dose for each participant is determined by going through a titration period on the first 14 days of study. The titration regimen is described in table 1.

Table 1.

Dose titration regimen for the investigational product

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 7 | |

| Week 1 |

<4 mg THC

50 mg CBD |

<6 mg THC

75 mg CBD |

<8 mg THC

100 mg CBD |

<10 mg THC

125 mg CBD |

<12 mg THC

150 mg CBD |

<14 mg THC

175 mg CBD |

<16 mg THC

200 mg CBD |

Morning:

Night:

|

Morning:

Noon:

Night:

|

morning:

Noon:

Night:  x2 x2 |

Morning:

Noon:  x2 x2 |

Morning

Noon:  x3 x3 |

Morning:

Noon:  x4 x4 |

Morning:

Noon:  x5 x5 |

| Day 8 | Day 9 | Day 10 | Day 11 | Day 12 | Day 13 | Day 14 | |

| Week 2 |

<18 mg THC

225 mg CBD |

<20 mg THC

250 mg CBD |

<22mgTHC

275 mg CBD |

<24 mg THC 300 mg CBD |

<26 mg THC

325 mg CBD |

<28 mg THC

350 mg CBD |

<30 mg THC

<30 mg THC

375 mg CBD |

Morning: x5 x5 |

Morning:  x6 x6 |

Morning: x7 x7 |

Morning:  x8 x8 |

Morning:  x8 x8 |

Morning: x8 x8 |

Morning:  x8 x8 |

25 mg CBD and <2 mg THC in a capsule.

25 mg CBD and <2 mg THC in a capsule.

CBD, cannabidiol; TCH, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol.

Titration period

A titration period is required to reach the optimal dose for each participant. The participants will begin taking an initial total dose of 50 mg of CBD and <4 mg THC or placebo. The dose will increase gradually for each participant depending on the effect of the study drug and the tolerance level of each participant. They will continue titration until an undesired side effect is experienced or the maximum dose of 375 mg of CBD and <30 mg of THC (+/-10%) is achieved. If an undesired side effect occurs, the participant will be tapered down to the last dose where no side effects were reported.

The titration regimen for this study was based on the principle of ‘start low and go slow’.37 Patients taking the approved CB nabiximols (Sativex) commence medication using a titration scheme for up to 2 weeks to determine the optimal drug dose. The pharmacokinetic variability of nabiximols is high between individuals, but low within individuals.38

After the titration phase, the participants will enter the maintenance period. They will continue taking the titrated dose for the remainder of the study.

Study procedures

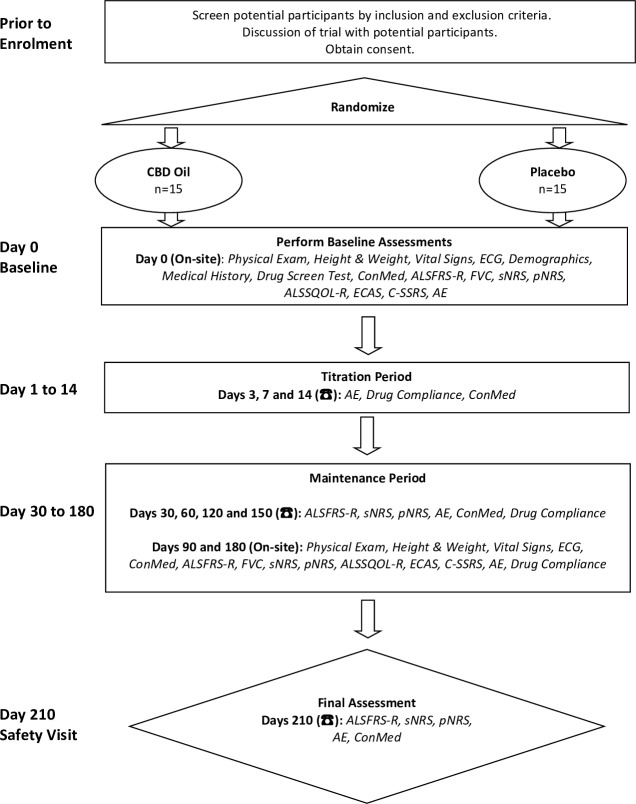

Thirty ALS/MND patients will be randomised in a 1:1 ratio to receive CannTrust CBD Oil or placebo (both in capsules). They will be stratified based on their age:<65 and >65 years. The treatment duration is 6 months with 1 month safety follow-up. They will be checked every month either face to face or via telephone and relevant data will be collected. The data of the patients will be stored in Research Electronic Data Capture at baseline and follow-up visits. Clinical data include demographics, medical history, El Escorial diagnosis, ALSFRS-R score, date of symptom onset and the site, physical examination, vital signs, laboratory tests, weight and height, concomitant medications, adverse events, drug compliance and study-related questionnaires. The participants will be advised to avoid opiates, alcohol and sleep medications due to the cumulative drug effects of cannabis. They will also be advised not to drive vehicles and operate heavy machinery while in the trial. Study procedures are summarised in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Summary of study procedures. AE, adverse event; ALSFRS-R, ALS Functional Rating Scale-Revised; ALSSQOL, ALS specific quality of life-Revised; CBD, cannabidiol; ConMed, concomitant medication; C-SSRS, Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale; ECAS, Edinburgh Cognitive and behavioural ALS Screen; FVC, forced vital capacity; pNRS, Numeric Rating Scale for pain; sNRS, Numeric Rating Scale for spasticity.

Randomisation

The randomisation command ralloc in Stata V. 9.0 will be used to perform stratified randomisation in this study (>65 and <65 years old). The GCUH biostatistician will generate stratified randomisation code blocks to ensure approximate balance (1:1) between the two arms (treatment and placebo). These blocks will be personally handed over or sent privately to trial pharmacists in a password-protected file. The allocation code blocks will be accessed only by trial pharmacists and will be stored in a password-protected computer. Trial pharmacists and biostatistician will not be involved in any other aspect of the study.

Blinding

To ensure the blinding of investigators and participants to study treatment, the study drug or placebo will be provided in identical packaging and labelling. Due to some natural variability in the colour of the study drug, which is batch dependent, the colour of the placebo has been matched to be the same as the average colour of the study drug. Study drug and placebo will be labelled with a unique label letter that will be used to assign treatment to the patient but will not indicate treatment allocation to the investigators or participants. No member of the study team and their extended staff, except for the trial pharmacists and biostatistician, will have access to the randomisation scheme during the conduct of the study. In the event of a medical emergency, where breaking the blind is required to provide medical care to the participant, the investigator will obtain the treatment assignment from trial pharmacists.

Sample size

To detect a clinically relevant difference of 3.0 points on the ALSFRS-R scale with a power of 90% at a significance level of 5% based on a two-sample t-test to compare treatment groups, it was calculated that a total sample size of 30 participants was required (G* Power V. 3.1.9.2). Sample size estimation was based on results from the Edaravone MCI-186–19 trial39 as their study population was similar to the target population of this trial, ie, <2 years since onset of first ALS symptom. A SD result of 2.4 units on the ALSFRS-R scale was chosen as it represented the largest pretreatment estimate from each of the treatment and control groups of Edaravone MCI-186–19 trial39 prior to observation or at baseline.

Statistical analyses

Efficacy outcomes will be analysed on an intention-to-treat basis. Primary outcomes will be analysed by comparing the difference of mean ALSFRS-R and FVC scores between groups at the end of the treatment period using linear regression. Statistical significance will be set at a two-sided level of 0.05. This simple analysis will be extended to include covariates such as gender and ALS onset site through linear regression.

Secondary outcomes will be analysed using with the same method as primary outcomes. Clinical endpoints (death and inability to swallow) will be assessed in a time-to-event analysis using Kaplan-Meier plots, log-rank tests and Cox proportional hazard analyses.

Safety data will be collected and summarised from baseline to day 210. Safety data will be listed by subject and summarised by treatment (active or placebo) using the number of subjects (n and percent) with events/abnormalities for categorical data. The nature and number of adverse events will be analysed using the Poisson test.

Exploratory outcome will be analysed by comparing the difference of mean ECAS scores between groups at the end of treatment using linear regression.

Patient and public involvement

The research question was asked by MND patients - whether cannabis has potential as a treatment drug. Neither patients nor the public were directly involved in the selection of outcome measures, design and implementation of the study.

Ethics and dissemination

The EMERALD trial is being conducted according to Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. This study is currently on Protocol V. 5.1 dated 31 March 2019. Study monitoring will be conducted by GCUH and the Health Service Research Directorate office. To ensure patient safety, Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) will meet regularly to review adverse events and safety data. DSMB is composed of academics and clinicians, including a biostatistician, all of whom are not directly involved in the study conduct. Study investigators will obtain consent from the participants. The consent form includes information about the study, the risks and benefits of joining the trial, study visits, collection and reporting of adverse events and compensation for trial-related harm. Participants are advised that they can withdraw from the study at any time. Study results will be presented at scientific conferences and published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Current study status

The EMERALD trial began enrolling patients in January 2019. We expect the trial to be completed in June 2021.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: BU and AS conceived and designed this study. BU drafted the study protocol and organised the study implementation. AS, SB, RB and ER refined the study protocol. BU drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This trial is supported by a grant from Gold Coast Hospital and Health Service and Gold Coast Hospital Foundation. The study drug and placebo are provided by CannTrust Inc.

Competing interests: The investigational product has been provided by CannTrust Inc.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study has been approved by the Institutional Review Board (Gold Coast Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee) – Reference No: HREC/17/QGC/293) in April 2018.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Kiernan MC, Vucic S, Cheah BC, et al. . Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 2011;377:942–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61156-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zarei S, Carr K, Reiley L, et al. . A comprehensive review of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Surg Neurol Int 2015;6:171 10.4103/2152-7806.169561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chiò A, Logroscino G, Hardiman O, et al. . Prognostic factors in ALS: a critical review. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2009;10:310–23. 10.3109/17482960802566824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ingre C, Roos PM, Piehl F, et al. . Risk factors for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin Epidemiol 2015;7:181–93. 10.2147/CLEP.S37505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown RH, Al-Chalabi A, Sclerosis AL. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2017;377:162–72. 10.1056/NEJMra1603471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Turner MR, Bowser R, Bruijn L, et al. . Mechanisms, models and biomarkers in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2013;14:19–32. 10.3109/21678421.2013.778554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carter GT, Rosen BS. Marijuana in the management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2001;18:264–70. 10.1177/104990910101800411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Walter L, Stella N. Cannabinoids and neuroinflammation. Br J Pharmacol 2004;141:775–85. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sinclair J. An introduction to cannabis and the endocannabinoid system. Australian Journal of Herbal Medicine 2016;28:107–25. [Google Scholar]

- 10. De Petrocellis L, Di Marzo V. An introduction to the endocannabinoid system: from the early to the latest concepts. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;23:1–15. 10.1016/j.beem.2008.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Scotter EL, Abood ME, Glass M. The endocannabinoid system as a target for the treatment of neurodegenerative disease. Br J Pharmacol 2010;160:480–98. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00735.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bilsland LG, Dick JRT, Pryce G, et al. . Increasing cannabinoid levels by pharmacological and genetic manipulation delay disease progression in SOD1 mice. FASEB J 2006;20:1003–5. 10.1096/fj.05-4743fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Witting A, Weydt P, Hong S, et al. . Endocannabinoids accumulate in spinal cord of SOD1 G93A transgenic mice. J Neurochem 2004;89:1555–7. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02544.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim K, Moore DH, Makriyannis A, et al. . AM1241, a cannabinoid CB2 receptor selective compound, delays disease progression in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur J Pharmacol 2006;542:100–5. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Raman C, McAllister SD, Rizvi G, et al. . Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: delayed disease progression in mice by treatment with a cannabinoid. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 2004;5:33–9. 10.1080/14660820310016813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shoemaker JL, Seely KA, Reed RL, et al. . The CB2 cannabinoid agonist AM-1241 prolongs survival in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis when initiated at symptom onset. J Neurochem 2007;101:87–98. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04346.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weydt P, Hong S, Witting A, et al. . Cannabinol delays symptom onset in SOD1 (G93A) transgenic mice without affecting survival. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 2005;6:182–4. 10.1080/14660820510030149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Laaris N, Good CH, Lupica CR. Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol is a full agonist at CB1 receptors on GABA neuron axon terminals in the hippocampus. Neuropharmacology 2010;59:121–7. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ramirez BG, et al. Prevention of Alzheimer's disease pathology by cannabinoids: neuroprotection mediated by blockade of microglial activation. J Neurosci 2005;25:1904–13. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4540-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. ALSUntangled Group ALSUntangled No. 16: cannabis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2012;13:400–4. 10.3109/17482968.2012.687264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Espejo-Porras F, Piscitelli F, Verde R, et al. . Changes in the endocannabinoid signaling system in CNS structures of TDP-43 transgenic mice: relevance for a neuroprotective therapy in TDP-43-related disorders. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2015;10:233–44. 10.1007/s11481-015-9602-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Amtmann D, Weydt P, Johnson KL, et al. . Survey of cannabis use in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2004;21:95–104. 10.1177/104990910402100206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gelinas D, Miller RG, Abood ME. A pilot study of safety and tolerability of delta 9-THC (Marinol) treatment for ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 2002;3. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weber M, Goldman B, Truniger S. Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) for cramps in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a randomised, double-blind crossover trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81:1135–40. 10.1136/jnnp.2009.200642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Riva N, Mora G, Sorarù G, et al. . Safety and efficacy of nabiximols on spasticity symptoms in patients with motor neuron disease (canals): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol 2019;18:155–64. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30406-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carter GT, Abood ME, Aggarwal SK, et al. . Cannabis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: hypothetical and practical applications, and a call for clinical trials. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2010;27:347–56. 10.1177/1049909110369531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tait RJ, Mackinnon A, Christensen H. Cannabis use and cognitive function: 8-year trajectory in a young adult cohort. Addiction 2011;106:2195–203. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03574.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gonzalez R, Schuster RM, Mermelstein RJ, et al. . Performance of young adult cannabis users on neurocognitive measures of impulsive behavior and their relationship to symptoms of cannabis use disorders. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2012;34:962–76. 10.1080/13803395.2012.703642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Urbi B, Owusu MA, Hughes I, et al. . Effects of cannabinoids in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) murine models: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Neurochem 2019;149:284–97. 10.1111/jnc.14639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moreno-Martet M, Espejo-Porras F, Fernández-Ruiz J, et al. . Changes in Endocannabinoid Receptors and Enzymes in the Spinal Cord of SOD1 G93ATransgenic Mice and Evaluation of a Sativex -like Combination of Phytocannabinoids: Interest for Future Therapies in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. CNS Neurosci Ther 2014;20:809–15. 10.1111/cns.12262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Russo EB. Taming THC: potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects. Br J Pharmacol 2011;163:1344–64. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01238.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Atakan Z. Cannabis, a complex plant: different compounds and different effects on individuals. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2012;2:241–54. 10.1177/2045125312457586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Devinsky O, Cilio MR, Cross H, et al. . Cannabidiol: pharmacology and potential therapeutic role in epilepsy and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Epilepsia 2014;55:791–802. 10.1111/epi.12631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhornitsky S, Potvin S. Cannabidiol in humans-the quest for therapeutic targets. Pharmaceuticals 2012;5:529–52. 10.3390/ph5050529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Queensland Health Clinical guidance: for the use of medicinal cannabis products in Queensland, 2017. Available: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0023/634163/med-cannabis-clinical-guide.pdf

- 36. Russo EB. Current therapeutic cannabis controversies and clinical trial design issues. Front Pharmacol 2016;7 10.3389/fphar.2016.00309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. MacCallum CA, Russo EB. Practical considerations in medical cannabis administration and dosing. Eur J Intern Med 2018;49:12–19. 10.1016/j.ejim.2018.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stott CG, White L, Wright S, et al. . A phase I study to assess the single and multiple dose pharmacokinetics of THC/CBD oromucosal spray. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2013;69:1135–47. 10.1007/s00228-012-1441-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Abe K, Aoki M, Tsuji S, et al. . Safety and efficacy of edaravone in well defined patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:505–12. 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30115-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.