Abstract

Objective

Home-time is an emerging patient-centred stroke outcome metric, but it is not well described in the population. We aimed to determine the association between 90-day home-time and global disability after stroke. We hypothesised that longer home-time would be associated with less disability.

Design

Hospital-based cohort study of patients with ischaemic stroke or intracerebral haemorrhage admitted to an acute care hospital between 1 April 2002 and 31 March 2013.

Setting

All regional stroke centres and a simple random sample of patients from all other hospitals across the province of Ontario, Canada.

Participants

We included 39 417 adult patients (84% ischaemic, 16% haemorrhage), 53% male, with a median age of 74 years. We excluded non-residents of Ontario, patients without a valid health insurance number, patients discharged against medical advice or those who failed to return from a pass, patients living in a long-term care centre at baseline and stroke events occurring in-hospital.

Primary outcome measure

Association between 90-day home-time, defined as the number of days spent at home in the first 90 days after stroke, obtained using linked administrative data and modified Rankin Scale score at discharge.

Results

Compared with people with no disability, those with minimal disability had less home-time (adjusted rate ratio (aRR) 0.96, 95% CI 0.93 to 0.98) and those with the most severe disability had the least home-time (aRR 0.05, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.05). We found no clinically relevant modification by stroke type, sex or study year. However, for a given level of disability, older patients experienced less home-time compared with younger patients.

Conclusions

Our results provide content validity for home-time to be used to monitor stroke outcomes in large populations or to study temporal trends. Older patients experience less home-time for a given level of disability, suggesting the need for stratification by age.

Keywords: stroke, organisation of health services, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Hospital-based analysis of home-time, a graded stroke outcome metric that can be derived from administrative data.

First study to assess the association between home-time and global disability in subgroups, including stroke type, sex, age groups and study year.

Lack of data on disability after hospital discharge.

Lack of data on social support or private funds, which may influence ability to return home.

Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of severe disability.1 2 The lack of a routinely collected graded stroke outcome metric is a critical limitation to population-based stroke outcome research. The modified Rankin Scale (mRS) is the most frequently used measure of functional outcome in stroke clinical research, but it cannot be routinely obtained for all patients as it requires prospective patient follow-up and testing.3 Home-time is a novel stroke outcome indicator that is correlated with the mRS when assessed in clinical trial populations with ischaemic stroke.4–6 Home-time is defined as the total number of days a patient is living outside of a healthcare institution after stroke. This metric is patient centred7 8 and is ideal for pragmatic studies evaluating real-world outcomes because it can be derived for large populations using administrative data.5 6

There are nevertheless several gaps in knowledge about home-time. Prior studies focused on patients with ischaemic strokes enrolled in clinical trials,4 9 and few have described the relationship between home-time and mRS in the general population.5 Understanding whether the association between home-time and mRS holds true in a population-based sample, in different stroke types, in important patient subgroups, as well as in different time periods is necessary to inform whether home-time can be used as an outcome metric to evaluate quality of stroke care. Finally, because home-time may be sensitive to the structures of healthcare systems, it is relevant to validate this metric in different jurisdictions.10

We aimed to determine the association between 90-day home-time and disability at discharge, measured using the mRS score, in a hospital-based cohort of patients with ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke. We hypothesised that home-time would be strongly associated with the mRS score and that this association would not be significantly modified by stroke type, temporal trends or patient demographics.

Methods

Cohort identification

We identified all hospital admissions for ischaemic stroke or intracerebral haemorrhage in the Ontario Stroke Registry (formerly known as the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network) between 1 April 2002 and 31 March 2013. The registry collected data on all consecutive patients with stroke seen in the emergency department or admitted to regional stroke centres and a simple random sample of patients from all other hospitals across Ontario, Canada’s most populous province with a population of 13 million people.11 We excluded patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage. Other exclusion criteria were patients aged less than 18 years, non-residents of Ontario or those without a valid health insurance number, patients discharged against medical advice or those who failed to return from a pass, patients living in a long-term care centre at baseline and any strokes occurring during hospitalisation for a different health condition. Only the first presentation was included in individuals who presented with stroke more than once during the study period.

Outcomes and covariates

The 90-day home-time was the primary outcome and was defined as the total number of days a patient was living outside of a healthcare institution in the first 90 days after stroke. Home-time was calculated for each individual patient using linked administrative health databases (online supplementary table 1) by subtracting the number of days spent in emergency care, acute care, inpatient rehabilitation, long-term care institution, as well as any rehospitalisations from the first 90 days after the date of admission for the index event. By definition, patients who died during the index hospitalisation have 0 home-time days. Patients who were discharged from healthcare institutions and subsequently died in the first 90 days after stroke may have accumulated home-time days. We also determined whether Ontario public home care services were provided to patients who were assumed to be at home. Canadian administrative databases include data on the entire population and have been extensively validated for research purposes.12 These datasets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analysed at ICES.13

bmjopen-2019-031379supp001.pdf (516.5KB, pdf)

Data on discharge mRS were collected in the registry through retrospective chart abstraction by trained chart abstractors, mainly nurses, with stroke expertise (<1% missing data). The mRS is an ordinal scale ranging from 0 for no symptoms, to 3 for moderate disability (able to walk without assistance but requiring some help), to 5 for severe disability (bedridden and requiring constant nursing care) and to 6 for death.3 Data validation by duplicate chart abstraction showed excellent agreement (kappa score or intraclass correlation coefficient of greater than 0.9) for key variables.14

The covariates in our analyses were age, sex, stroke type (ischaemic stroke vs intracerebral haemorrhage), stroke severity (mild stroke defined as a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale <5), Charlson comorbidity index (dichotomised to <2 or ≥2), independence in activities of daily living prior to the index stroke, location of residency (small population centre: less than 10 000; medium population centre: 10 000–100 000 and large urban population centre: >100 000) and neighbourhood income quintile. The covariates were obtained from the Ontario Stroke Registry, except for the Charlson comorbidity index, the location of residency and the neighbourhood income quintile, which were obtained from linked administrative data.15

Statistical methods

Patient characteristics were described using proportions for categorical variables, mean and SD, and median with 25th and 75th percentiles (Q1,Q3) for continuous variables. We used Spearman’s rank correlation to quantify the correlation between 90-day home-time and discharge mRS stratified by stroke type. Because the distribution of home-time is bucket-shaped with peaks around its minimum value (0) and maximum value (90), we considered four regression models: the negative binomial model, the Poisson model and their respective zero-inflated counterparts.16 The zero-inflated negative binomial regression model best fit our observed data. Accordingly, this model was used to determine the association between discharge mRS and 90-day home-time with adjustment for the covariates. The zero-inflated negative binomial model yields two sets of regression coefficients: one from an underlying logistic model that is modelling excess zeros and one from an underlying negative binomial model for counts. To simplify presentation and interpretation of the two sets of regression coefficients, we used a previously described method for summarising the effect of the predictor variables to yield an adjusted summary rate ratio (aRR), which is interpreted as the ratio of the mean number of home-time days among those exposed to the covariate of interest to the mean number of home-time days among those who were not.16 We used bootstrapping to obtain 95% CIs. In order to determine whether the association between home-time and mRS was significantly modified by stroke type, sex, age and study year, we used likelihood ratio tests to compare the models with and without the appropriate multiplicative interaction terms. If a statistically significant interaction was present (defined as p<0.05), we reported the stratum-specific aRR derived from the model with the appropriate main effects and interaction terms.

Research ethics approval

ICES is an independent, non-profit research institute whose legal status under Ontario’s health information privacy law allows it to collect and analyse healthcare and demographic data, without consent, for health system evaluation and improvement. The use of data in this project was authorised under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act. We have permission to access the data.

Results

Our study sample consisted of 39 417 patients (84% ischaemic stroke and 16% intracerebral haemorrhage), with a median (Q1,Q3) age of 74 years (63,82), of whom 53% were male. The median in-hospital length of stay was 9 days (5,18). Table 1 describes patient characteristics, disability at discharge, the median 90-day home-time, and the location of the patient at 90 days by stroke type. The median 90-day home-time was 55 days (0,82) for patients with ischaemic stroke and 0 (0,58) for those with intracerebral haemorrhage. By definition, patients who died during the index hospitalisation (n=6052, 15%) did not accumulate any home-time days.

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics, disability at discharge and 90-day location

| All (n=39 417) |

Ischaemic stroke (n=32 982) |

ICH (n=6435) |

|

| Median age (Q1,Q3) | 74 (63,82) | 75 (64,83) | 71 (59,80) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 20 693 (52.5) | 17 201 (52.2) | 3492 (54.3) |

| Median NIHSS (Q1,Q3) | 5 (2,12) | 5 (2,11) | 9 (2,16) |

| Minor stroke (NIHSS <5), n (%) | 16 113 (40.9) | 14 205 (43.1) | 1908 (29.7) |

| Home location, n (%) | |||

| Large urban | 31 238 (79.3) | 26 028 (78.9) | 5210 (81.0) |

| Medium population | 3120 (7.9) | 2627 (8.0) | 493 (7.7) |

| Small population | 5059 (12.8) | 4327 (13.1) | 732 (11.4) |

| Neighbourhood income quintile, n (%) | |||

| Lowest | 9161 (23.2) | 7748 (23.5) | 1413 (22.0) |

| Next to lowest | 8446 (21.4) | 7069 (21.4) | 1377 (21.4) |

| Middle | 7483 (19.0) | 6217 (18.8) | 1266 (19.7) |

| Next to highest | 7083 (18.0) | 5897 (17.9) | 1186 (18.4) |

| Highest | 7244 (18.4) | 6051 (18.3) | 1193 (18.5) |

| Baseline independence, n (%) | 29 688 (75.3) | 24 691 (74.9) | 4997 (77.7) |

| CCI ≥2, n (%) | 20 851 (52.9) | 17 775 (53.9) | 3076 (47.8) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 10 095 (25.6) | 8869 (26.9) | 1226 (19.1) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 27 156 (68.9) | 23 136 (70.1) | 4020 (62.5) |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 15 160 (38.5) | 13 307 (40.3) | 1853 (28.8) |

| Active smoking, n (%) | 7174 (18.2) | 6251 (19.0) | 923 (14.3) |

| Prior stroke, n (%) | 7131 (18.1) | 6231 (18.9) | 900 (14.0) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 7150 (18.1) | 6232 (18.9) | 918 (14.3) |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 9168 (23.3) | 8210 (24.9) | 958 (14.9) |

| Dementia, n (%) | 2780 (7.1) | 2342 (7.1) | 438 (6.8) |

| Median acute care length of stay (Q1,Q3) | 9 (5,18) | 9 (5,17) | 10 (4,24) |

| Discharge mRS | |||

| Median mRS (Q1,Q3) | 3 (2,4) | 3 (2,4) | 4 (3,6) |

| mRS=0, n (%) | 2513 (6.4) | 2263 (6.8) | 250 (3.9) |

| mRS=1, n (%) | 4495 (11.4) | 4073 (12.3) | 422 (6.6) |

| mRS=2, n (%) | 6429 (16.3) | 5896 (17.9) | 533 (8.3) |

| mRS=3, n (%) | 8413 (21.3) | 7423 (22.5) | 990 (15.4) |

| mRS=4, n (%) | 9372 (23.8) | 7772 (23.6) | 1600 (24.9) |

| mRS=5, n (%) | 2143 (5.4) | 1609 (4.9) | 534 (8.3) |

| mRS=6, n (%) | 6052 (15.4) | 3946 (12.0) | 2106 (32.7) |

| Median 90-day home-time (Q1,Q3) | 47 (0,81) | 55 (0,82) | 0 (0,58) |

| Mean 90-day home-time (SD) | 42 (36) | 46 (36) | 26 (34) |

| 90-day location, n (%) | |||

| Acute care | 1686 (4.3) | 1367 (4.1) | 319 (5.0) |

| Rehabilitation | 1816 (4.6) | 1412 (4.3) | 404 (6.3) |

| LTC/CCC | 2910 (7.4) | 2408 (7.3) | 502 (7.8) |

| Death | 8083 (20.5) | 5628 (17.1) | 2455 (38.2) |

| Home with home care | 2140 (5.4) | 1913 (5.8) | 227 (3.5) |

| Home without home care | 22 782 (57.8) | 20 254 (61.4) | 2528 (39.3) |

Modified Rankin Scale (mRS): 0: no symptoms, 1: no significant disability despite symptoms, 2: slight disability, 3: moderate disability, 4: moderately severe disability, 5: severe disability and 6: dead.

CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; ICH, intracerebral haemorrhage; LTC/CCC, long-term care/complex continuing care; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; Q1,Q3, 25th and 75th percentile.

More 90-day home-time (ie, more days at home) was associated with lower mRS at discharge (ie, less disability) for ischaemic stroke (Spearman correlation coefficient −0.78) and intracerebral haemorrhage (Spearman correlation coefficient −0.80). Table 2 shows the median (Q1,Q3) and mean (SD) home-time for each mRS category as well as the results of the multivariable zero-inflated negative binomial analyses.

Table 2.

Adjusted summary rate ratio of home-time by predictor variables using multivariable zero-inflated negative binomial model

| Predictor variables | Median home-time (Q1,Q3) |

Mean home-time (SD) |

aRR (95% CI) |

| Age categories (years) | |||

| 21–60 | 68 (12,84) | 53 (35) | Reference |

| 61–70 | 60 (0,83) | 48 (36) | 0.97 (0.95 to 0.99) |

| 71–80 | 46 (0,80) | 42 (36) | 0.94 (0.92 to 0.95) |

| ≥80 | 12 (0,71) | 32 (35) | 0.89 (0.87 to 0.91) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 40 (0,79) | 40 (36) | Reference |

| Male | 53 (0,82) | 45 (36) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.02) |

| mRS category | |||

| mRS 0 | 84 (81,87) | 80 (16) | Reference |

| mRS 1 | 84 (79,86) | 77 (19) | 0.96 (0.93 to 0.98) |

| mRS 2 | 81 (68,85) | 73 (21) | 0.92 (0.90 to 0.94) |

| mRS 3 | 57 (29,76) | 50 (29) | 0.60 (0.59 to 0.62) |

| mRS 4 | 9 (0,45) | 23 (27) | 0.23 (0.22 to 0.24) |

| mRS 5 | 0 (0,3) | 7 (17) | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.06) |

| Home location | |||

| Large urban | 46 (0,81) | 42 (36) | Reference |

| Medium population | 50 (0,82) | 43 (37) | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.07) |

| Small population | 53 (0,82) | 44 (37) | 1.02 (1.00 to 1.04) |

| Neighbourhood income quintile | |||

| Lowest | 43 (0,80) | 41 (36) | Reference |

| Next to lowest | 46 (0,81) | 42 (36) | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.04) |

| Middle | 49 (0,81) | 43 (36) | 1.02 (1.00 to 1.04) |

| Next to highest | 50 (0,81) | 43 (36) | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.04) |

| Highest | 50 (0,82) | 43 (36) | 1.02 (1.00 to 1.05) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | |||

| Score <2 | 62 (0,83) | 49 (36) | Reference |

| Score ≥2 | 30 (0,76) | 36 (36) | 0.91 (0.90 to 0.93) |

| Preadmission dependence | |||

| Dependent | 7 (0,68) | 30 (35) | Reference |

| Independent | 56 (0,82) | 46 (36) | 1.06 (1.04 to 1.08) |

| Stroke severity | |||

| Mild (NIHSS <5) | 78 (46,85) | 62 (30) | Reference |

| Severe (NIHSS ≥5) | 5 (0,63) | 29 (34) | 0.82 (0.80 to 0.83) |

aRR, adjusted rate ratio; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; Q1,Q3, first and third quartile.

We showed that people with higher disability at discharge from the acute care hospitalisation experienced less home-time. Compared with people discharged with no disability (mRS=0), those discharged with minimal disability had slightly less home-time (mRS=1, aRR 0.96, 95% CI 0.93 to 0.98), but those discharged with the most severe disability had the least home-time (mRS=5, aRR 0.05, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.05). In addition, older people, those with a higher comorbidity burden and those with higher stroke severity experienced less home-time, while those who were independent at baseline experienced more home-time (table 2). Patients living in medium urban regions had slightly more home-time than those living in small towns or in large urban regions. Home-time was not associated with the neighbourhood income quintile, a proxy for socioeconomic status.15

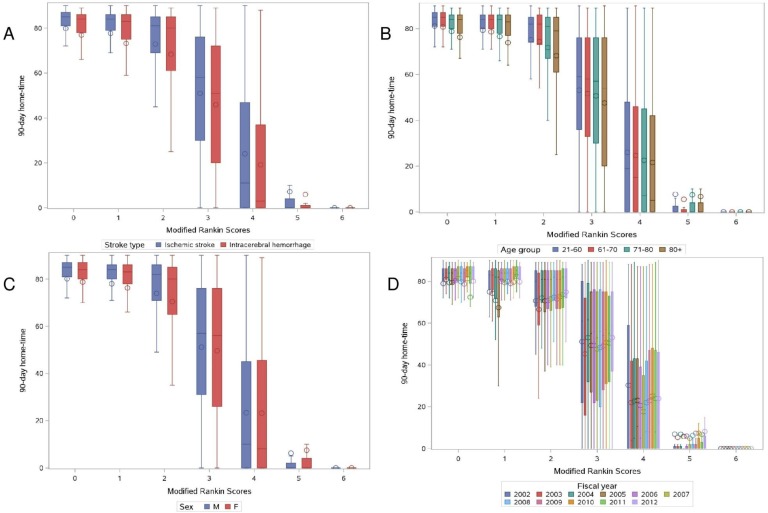

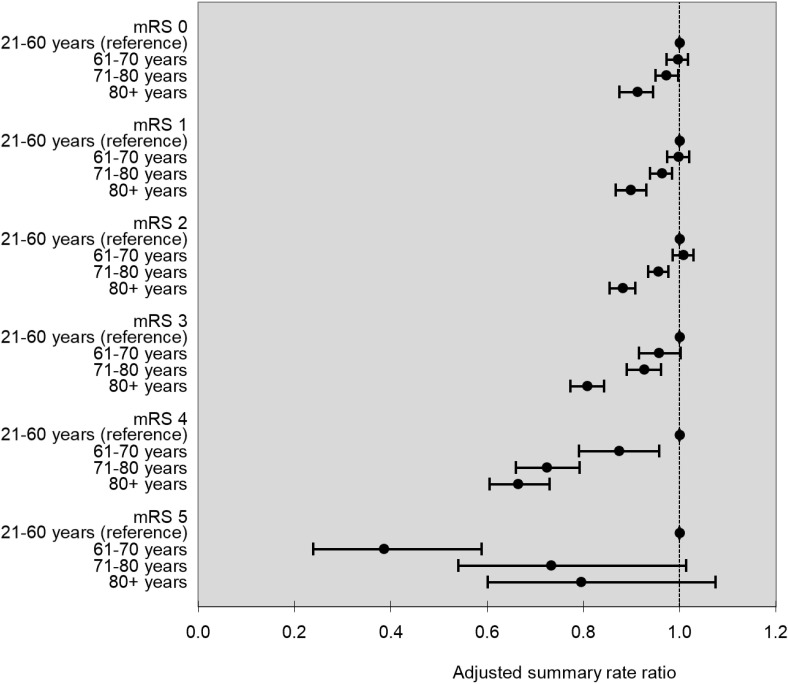

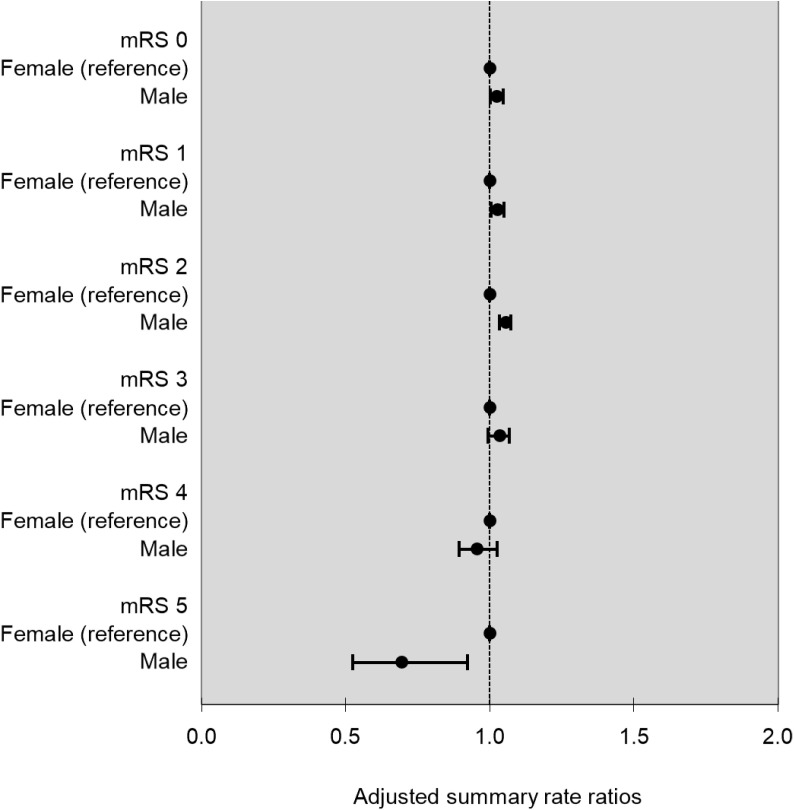

Figure 1 shows the relationship between discharge mRS and 90-day home-time by stroke type, age, sex and study year. There was no evidence of effect modification by stroke type (p for interaction=0.06), but there was a statistically significant interaction for age, sex and study year (p for interaction <0.001 for all three covariates). In the subanalysis by age, we observed that for almost all levels of the mRS, except those with the most severe disability, older patients experienced less home-time compared with their younger counterparts (figure 2). In the subanalysis by sex, we observed that compared with women, men experienced slightly more home-time in the subgroup of patients discharged with lower disability (mRS=1, aRR (95% CI) 1.02 (1.00 to 1.05), mRS=2, aRR (95% CI) 1.03 (1.00 to 1.05) and mRS=3, aRR (95% CI) 1.05 (1.03 to 1.07)), but men had less home-time among those with the most severe disability (mRS=5, aRR (95% CI) 0.69 (0.52 to 0.92), figure 3). Finally, in the subanalysis by study years, despite a statistically significant p value for interaction, we did not observe any consistent or clinically meaningful trends in effect modification (online supplementary figure 1).

Figure 1.

Box plots of home-time by MRS stratified by stroke type (A), age (B), sex (C) and study years (D). mRS, modified Rankin Scale.

Figure 2.

Age-specific adjusted summary rate ratio for 90-day home-time by mRS with ages 21–60 years as the reference group. mRS, modified Rankin Scale.

Figure 3.

Sex-specific adjusted summary rate ratio for 90-day home-time by mRS with female as the reference group. mRS, modified Rankin Scale.

Discussion

In this large hospital-based study of patients with stroke, we demonstrated that 90-day home-time was associated with global disability as measured by the mRS at discharge, for both ischaemic stroke and intracerebral haemorrhage and that this association was stable over an 11-year period. We showed a clear gradient between home-time and functional outcomes, across the levels of disability measured by the mRS, with people discharged from hospital with the highest disability experiencing the least home-time. In addition, home-time was responsive to covariates known to be associated with stroke outcomes as people who were older, dependent at baseline, had higher comorbidity burden or presented with severe strokes had less home-time.17 18

Home-time has been identified as a patient-centred outcome in stroke7 as well as in other medical conditions, such as cancer.8 This metric is associated with healthcare costs and is important to policy makers.10 19 With the availability of new stroke treatments, for example, acute revascularisation treatments up to 24 hours after stroke onset,20–22 systematic evaluation of outcomes with a graded and patient-centred metric is urgently needed for monitoring the quality and equity of care across populations. Our findings support the use of home-time derived from administrative data to study real-world stroke outcomes as well as in pragmatic clinical trials.23

Our inclusion of patients with intracerebral haemorrhage is important because acute treatment options are limited for this condition and systematic evaluation of outcomes may be particularly relevant for testing potential treatments or identifying prognostic markers.24 A recent study reported that discharge mRS is associated with 90-day home-time after admission for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage,25 but the association between home-time and mRS has not yet been reported in patients with intracerebral haemorrhage. Furthermore, the temporal stability of the relationship between home-time and mRS is important for studies on temporal trends in stroke outcomes. The sex differences in the relationship between home-time and mRS are of small magnitude, suggesting that home-time is a valid indicator for poststroke disability in both men and women.

In the stratified analysis by age, we found that compared with younger patients, older ones with the same degree of disability at discharge experienced less home-time. For example, considering that the mean home-time for patients discharged with mild disability (mRS=1) was 77 days, an aRR of 0.96 for patients aged 71–80 years compared with those aged 21–60 years translates into a difference of 3 days and an aRR of 0.90 for those older than 80 years translates into a difference of 8 days. This gradient was not seen in patients with severe disability (mRS=5), likely because few home-time days were accumulated overall in this category. Older patients are likely experiencing less home-time compared with younger ones because of more comorbid medical illnesses, poststroke complications and higher pre-stroke dependence.17 18 Stratified analyses by age groups may be necessary when using home-time to investigate outcomes after stroke.

Our findings are consistent with other studies calibrating home-time with the mRS in patients with ischaemic stroke enrolled in clinical trials4 6 9 as well as in US Medicare beneficiaries admitted to hospital with ischaemic stroke.5 26 Home-time is likely influenced by the organisation of healthcare systems.6 10 Although we were unable to perform direct comparisons, we found that the median home-time after ischaemic stroke in Ontario (55 days (0,82)) was less than that reported in the U.S. (79 days (52,86)),5 suggesting that home-time should be calibrated in the setting where it is intended to be used. A recent study using data from the Scottish National Health Service reported a mean home-time of 49 days after ischaemic stroke and 27 days after intracerebral haemorrhage,27 which is similar to our findings (46 days after ischaemic stroke and 26 days after intracerebral haemorrhage). Both Canadian and Scottish health systems operate under a single-payer universal healthcare model. Understanding home-time in different health systems will inform the use of this metric as a pragmatic outcome in multinational studies.

The strengths of our study are its population-based design, the inclusion of patients with intracerebral haemorrhages, the large sample size and the long study duration allowing for the evaluation of temporal trends. Our study nevertheless has limitations. First, the registry database only includes mRS at the time of discharge and the 90-day mRS was not available for analysis. While disability may change between discharge and 90 days, early disability has been shown to be a predictor of outcome at 90 days.28 Furthermore, we showed strong associations between home-time and discharge mRS in subgroup analyses, providing validity for the clinical relevance of home-time. Second, returning home may be contingent on social support or private funds, which are not captured in the administrative data calculation of home-time. We did however include neighbourhood income quintile as a measure of socioeconomic status and did not find an association with home-time. We also included the use of publicly funded home care services, which may range from a few hours a week to a few hours a day for assistance with activities of daily living or instrumental activities of daily living, but these do not include around the clock support. Finally, admission to long-term care may be underestimated prior to the fiscal year 2009/2010 because the Continuing Care Reporting System Long-Term Care database was incomplete,29 but we did not find any clinically meaningful differences in the association between mRS and home-time by study years.

Conclusions

Home-time is associated with global disability after ischaemic stroke and intracerebral haemorrhage. Its key advantage is that it can be calculated using routinely collected administrative data, allowing for the measurement of stroke outcomes for large populations. Our findings inform the application of home-time as a quality indicator of stroke care and its use as a pragmatic outcome in stroke health services research.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @YuAmyyu, @moirakapral

Contributors: AYXY contributed to the study concept and design, interpretation of data, drafting and revision of the manuscript. JF and JP contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data and revision of the manuscript. PCA contributed to data analysis and interpretation and revision of the manuscript. EES contributed to the study concept and design, interpretation of data and revision of the manuscript. MKK contributed to the study concept and design, acquisition and interpretation of data and revision of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Catalyst Grant number 385 156. Drs Austin and Kapral hold Mid-Career Investigator Awards from the Heart & Stroke Foundation of Canada.

Disclaimer: The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed in the material are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of CIHI.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Krueger H, Koot J, Hall RE, et al. . Prevalence of individuals experiencing the effects of stroke in Canada: trends and projections. Stroke 2015;46:2226–31. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heart and Stroke Foundation Stroke report 2016, 2016. Available: http://www.strokebestpractices.ca/index.php/news-feature/stroke-report-16-just-released/]. Available from: http://www.strokebestpractices.ca/index.php/news-feature/stroke-report-2016-just-released/[Accessed Mar 2017].

- 3. Quinn TJ, Dawson J, Walters MR, et al. . Functional outcome measures in contemporary stroke trials. Int J Stroke 2009;4:200–5. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00271.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Quinn TJ, Dawson J, Lees JS, et al. . Time spent at home poststroke: "home-time" a meaningful and robust outcome measure for stroke trials. Stroke 2008;39:231–3. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.493320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fonarow GC, Liang L, Thomas L, et al. . Assessment of Home-Time after acute ischemic stroke in Medicare beneficiaries. Stroke 2016;47:836–42. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yu AYX, Rogers E, Wang M, et al. . Population-Based study of home-time by stroke type and correlation with modified Rankin score. Neurology 2017;89:1970–6. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xian Y, O'Brien EC, Fonarow GC, et al. . Patient-Centered research into outcomes stroke patients prefer and effectiveness research: implementing the patient-driven research paradigm to aid decision making in stroke care. Am Heart J 2015;170:36–45. 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Groff AC, Colla CH, Lee TH. Days spent at home — a patient-centered goal and outcome. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1610–2. 10.1056/NEJMp1607206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mishra NK, Shuaib A, Lyden P, et al. . Home time is extended in patients with ischemic stroke who receive thrombolytic therapy: a validation study of home time as an outcome measure. Stroke 2011;42:1046–50. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.601302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barnett ML, Grabowski DC, Mehrotra A. Home-to-Home time — measuring what matters to patients and payers. N Engl J Med 2017;377:4–6. 10.1056/NEJMp1703423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) Ontario stroke registry, 2017. Available: http://www.ices.on.ca/Research/Research-programs/Cardiovascular/Ontario-Stroke-Registry [Accessed 27 Aug 2019].

- 12. Juurlink D, Preyra C, Croxford R, et al. . Canadian Institute for health information discharge Abstract database: a validation study Toronto: ICES, 2006. Available: https://www.ices.on.ca/publications/atlases-and-reports/2006/canadian-institute-for-health-information [Accessed Aug 2019].

- 13. ICES ICES data, discovery, better health. Available: https://www.ices.on.ca/ [Accessed Sep 2019].

- 14. Kapral MK, Hall R, Stamplecoski M, et al. . Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network - Report on the 2008/09 Ontario Stroke Audit Toronto: ICES. Available: http://www.ices.on.ca/~/media/Files/Atlases-Reports/2011/RCSN-2008-09-Ontario-stroke-audit/Full%20report.ashx [Accessed Aug 2019].

- 15. Kapral MK, Fang J, Chan C, et al. . Neighborhood income and stroke care and outcomes. Neurology 2012;79:1200–7. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826aac9b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weaver CG, Ravani P, Oliver MJ, et al. . Analyzing hospitalization data: potential limitations of poisson regression. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015;30:1244–9. 10.1093/ndt/gfv071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smith EE, Shobha N, Dai D, et al. . Risk score for in-hospital ischemic stroke mortality derived and validated within the get with the Guidelines–Stroke program. Circulation 2010;122:1496–504. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.932822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rost NS, Bottle A, Lee J-M, et al. . Stroke severity is a crucial predictor of outcome: an international prospective validation study. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5:e002433 10.1161/JAHA.115.002433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Andersen SK, Croxford R, Earle CC, et al. . Days at home in the last 6 months of life: a Patient-Determined quality indicator for cancer care. J Oncol Pract 2019;15:e308–15. 10.1200/JOP.18.00338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Albers GW, Marks MP, Kemp S, et al. . Thrombectomy for stroke at 6 to 16 hours with selection by perfusion imaging. N Engl J Med 2018;378:708–18. 10.1056/NEJMoa1713973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nogueira RG, Jadhav AP, Haussen DC, et al. . Thrombectomy 6 to 24 hours after stroke with a mismatch between deficit and infarct. N Engl J Med 2018;378:11–21. 10.1056/NEJMoa1706442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thomalla G, Simonsen CZ, Boutitie F, et al. . Mri-Guided thrombolysis for stroke with unknown time of onset. N Engl J Med 2018;379:611–22. 10.1056/NEJMoa1804355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li G, Sajobi TT, Menon BK, et al. . Registry-Based randomized controlled trials- what are the advantages, challenges, and areas for future research? J Clin Epidemiol 2016;80:16–24. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cordonnier C, Demchuk A, Ziai W, et al. . Intracerebral haemorrhage: current approaches to acute management. Lancet 2018;392:1257–68. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31878-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stienen MN, Smoll NR, Fung C, et al. . Home-Time as a surrogate marker for functional outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2018;49:3081–4. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.022808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. O'Brien EC, Xian Y, Xu H, et al. . Hospital variation in Home-Time after acute ischemic stroke: insights from the PROSPER study (patient-centered research into outcomes stroke patients prefer and effectiveness research). Stroke 2016;47:2627–33. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McDermid I, Barber M, Dennis M, et al. . Home-Time is a feasible and valid stroke outcome measure in national datasets. Stroke 2019;50:1282–5. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.023916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ovbiagele B, Lyden PD, Saver JL, et al. . Disability status at 1 month is a reliable proxy for final ischemic stroke outcome. Neurology 2010;75:688–92. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181eee426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Canadian Association for Health Services and Policy Research Conference Validation of incident long-term care admissions in Ontario using administrative data (oral presentation). Toronto, Ontario, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-031379supp001.pdf (516.5KB, pdf)