Abstract

Background:

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune condition affecting hair-bearing regions of the body. Few studies worldwide have focused exclusively on beard alopecia areata (BAA).

Aims:

To describe the clinical associations, comorbidities, and dermoscopy of BAA.

Materials and Methods:

Forty-six patients with BAA were recruited for this hospital-based cross-sectional study. Patients with disease onset of less than 1 month, patches showing extension, and appearance of new patches within the past 1 month were grouped under active disease. Dermoscopy was performed using handheld polarized dermoscope. Chi-square test was applied to know the various associations. P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. STATA 11.2 was used for analysis of data.

Results:

The mean age was 31.07 ± 8.72 years. The majority (50%) belonged to 20–29 age group. Twenty-two (48%) patients had active disease. Fourteen (30.43%) patients had extra-beard manifestation of AA. Statistically significant association was noted between active disease and extra-beard manifestation (P = 0.034). Diabetes mellitus and hypertension were noted in one and three patients, respectively. Alcohol abuse was noted in six patients and smoking in five patients. Dermoscopic findings such as black dots, short vellus hair, tapering hair, nonfollicular white dots, regrowing hair, yellow dots, and black dots were similar to findings noted in AA. Uncommon findings such as peripilar sign, i-hair, perifollicular hemorrhage, and tulip hair were observed in BAA.

Limitations:

Small sample size, lack of follow-up.

Conclusion:

Trichoscopy of BAA may reveal newer nonfollicular findings, in addition to the follicular findings already described in literature for AA.

Keywords: Alopecia areata, alopecia barbae, beard, dermoscopy, trichoscopy

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune-mediated T-cell attack on hair follicles resulting in patchy hair loss leading to unsightly appearance.[1] With a prevalence rate of upto 0.2%, the lifetime risk of developing AA stands at 2%.[2,3]

Although it can affect any hair-bearing region of the body, it is particularly noticeable when it involves cosmetically important areas such as the scalp, moustache, eyebrows, eyelashes, and beard. Very often, involvement of these sites can lead to psychological disturbances such as embarrassment, low self-esteem, and depression.[4]

AA affecting the beard in postpubertal men is a distinct clinical entity, often necessitating timely assessment and management. Studies on dermoscopy of beard alopecia areata (BAA) are limited.[5,6] Hence, this study was conducted to describe the clinical associations, comorbidities, and dermoscopy of BAA.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in the Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy of Justice K.S. Hegde Charitable Hospital attached to K.S. Hegde Medical Academy. Institutional ethical committee clearance was obtained prior to the start of this cross-sectional study. Written informed consent was taken from all the participants.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Smooth bald patches of nonscarring alopecia affecting the beard with no clinical evidence of erythema, scale, or crust. (2) Males above 16 years of age. Exclusion criteria: (1) Patients who had received treatment for the current episode of BAA in both topical and systemic forms. (2) Patients with alopecia universalis and alopecia totalis. (3) Patients with exclusive scalp, eyebrow, eyelash, or moustache involvement with no bald patch on the beard region. (4) Clinical mimics of BAA were further excluded on dermoscopy; scarring alopecia was excluded by the presence of follicular openings and trichotillomania (TTM) by the absence of predominance of broken hair of different lengths and trichoptilosis.[7] Those with disease onset of less than 1 month, patches showing extension, and appearance of new patches within the past 1 month were grouped under active disease. Dermoscopy was performed using a handheld polarized dermoscope (Dermlite DL4; 3Gen Inc., San Juan Capistrano, CA, USA) providing ×10 magnification with the Focus Dial set to position “0.” The images were captured with iPhone (iPhone 7; Apple Inc., CA, USA) and were then evaluated as saved photos on computer screen. The images were digitally zoomed up to ×20 magnification while analyzing the findings.

Data was collected on a prestructured proforma regarding age, duration of BAA, activity, triggering event, comorbidities, substance abuse, number of lesions, pattern of alopecia, associated involvement of sites other than beard, and dermoscopic findings.

Statistical analysis of data was carried out using mean and range for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. Chi-square test was applied to look for associations. P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. STATA 11.2 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) was used for analysis of data.

Results

A total of 46 subjects were enrolled in the study. The mean age of our patients was 31.07 ± 8.72 years. The youngest patient was 19 years of age and the oldest was 59 years of age. The majority (50%) of the patients belonged to 20–29 age group. The average duration of BAA prior to presentation was 5.73 ± 9.01 months. Twenty-two (48%) patients had active disease at the time of consultation.

Seven (15.22%) patients had a history of recurrence of AA. One (2.17%) patient had a family history of atopy. None of the patients had a personal history of atopy or family history of AA. Diabetes mellitus and hypertension were noted in one (0.17%) and three (6.52%) patients, respectively. Alcohol abuse was seen in six (13.04%) patients and smoking (10.84%) in five patients.

Twenty-nine (63.04%) patients had more than one alopecic patch, while 17 (36.95%) patients had a single patch [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

Clinical image of alopecia areata affecting the beard. Note the relative sparing of nonpigmented hair in the alopecic patch

Figure 2.

Clinical image of alopecia areata affecting the beard

Fourteen (30.43%) patients had extra-beard manifestation of AA. Scalp involvement was seen in 13 patients (28.26%), eyebrow and moustache involvement in 3 patients each (6.52%), while eyelash and limb involvement were noted in 2 patients each (4.35%). Of the 13 patients who had concomitant scalp involvement, 8 patients had vertex involvement, 7 patients had occipital, 5 patients had frontal, and 4 patients had temporal and parietal involvement each. Statistically significant association was present between active disease and extra-beard manifestation (P = 0.034).

Four (8.69%) patients had nail findings such as pitting (2), longitudinal striations (1), and longitudinal melononychia (1).

On dermoscopy, the majority showed dermoscopic findings while four patients showed no dermoscopic findings apart from the presence of follicular openings [Figures 3–8]. The most common findings were black dots and short vellus hair noted in 18 (39.13%) patients each [Table 1].

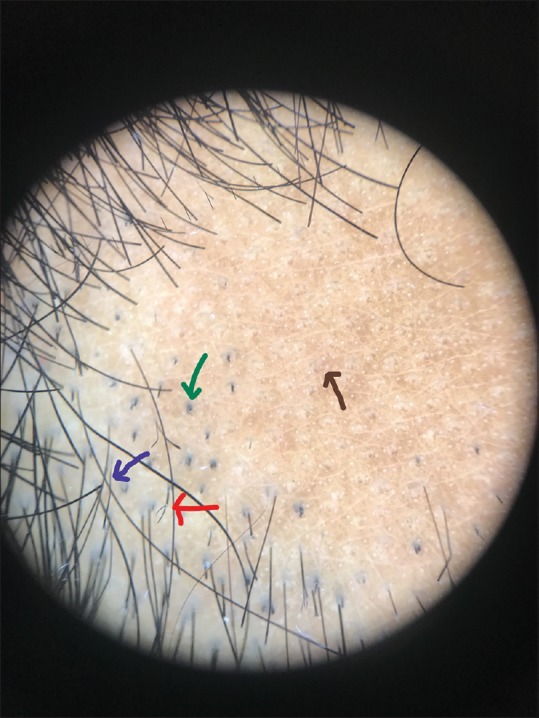

Figure 3.

Dermoscopic image (×10 magnification polarized mode) showing black dots (green arrow), tapering hair (blue arrow), broken hairs with frayed ends (red arrow), and nonfollicular white dots (black arrow)

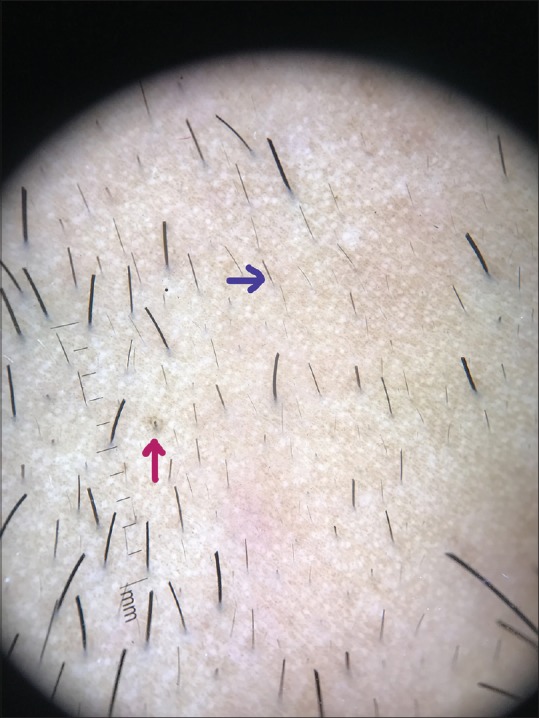

Figure 8.

Dermoscopic image (×10 magnification polarized mode) showing ihair (magenta arrow) and tapering hair (blue arrow)

Table 1.

Dermoscopic findings in BAA

| Dermoscopic findings | No. of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Black dots | 18 (39.13) |

| Short vellus hair | 18 (39.13) |

| Tapering hair | 14 (30.43) |

| White dots (nonfollicular) | 14 (30.43) |

| Regrowing hair | 14 (30.43) |

| Yellow dots | 13 (28.26) |

| White dots (follicular oriented) | 9 (19.57) |

| Broken hair | 9 (19.57) |

| Blotchy erythema | 8 (17.39) |

| Peripilar sign | 8 (17.39) |

| Hem-like pigment pattern | 5 (11.11) |

| Vascular network | 3 |

| Honeycomb pigment pattern | 2 |

| Coudability sign | 2 |

| i-hair | 1 |

| Perifollicular hemorrhage | 1 |

| Tulip hair | 1 |

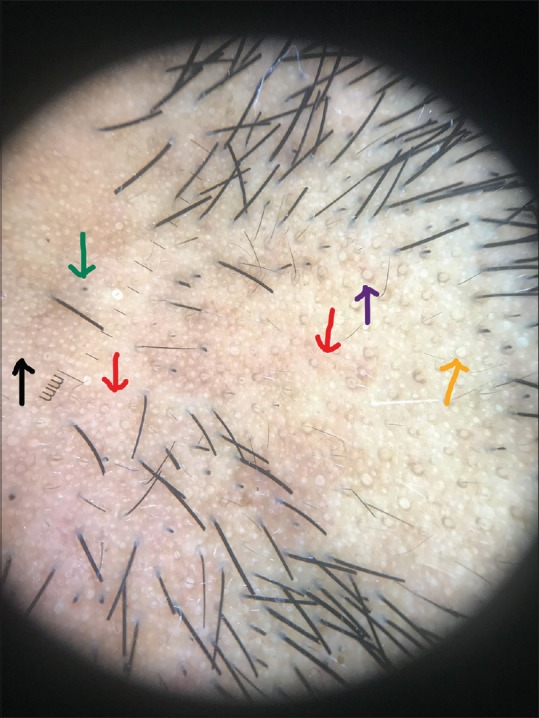

Figure 4.

Dermoscopic image (×10 magnification polarized mode) showing nonfollicular white dots (black arrow), yellow dots (orange arrow), peripilar sign (purple arrow), black dots (green arrow), and blotchy erythema (red arrow)

Figure 5.

Dermoscopic image (×10 magnification polarized mode) showing perifollicular hemorrhage (green arrow) and tapering hair (blue arrow)

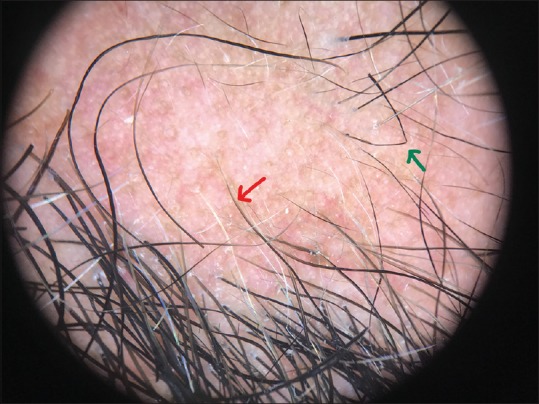

Figure 6.

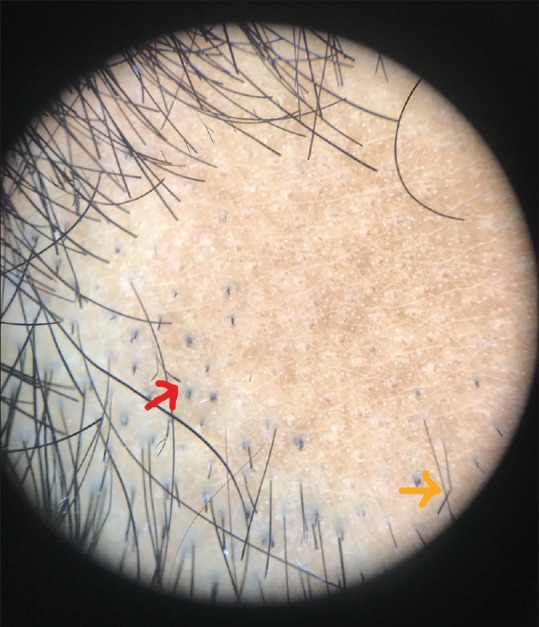

Dermoscopic image (×10 magnification polarized mode) showing coudability sign (green arrow) and tapering hair (red arrow)

Figure 7.

Dermoscopic image (×10 magnification polarized mode showing tulip hair (red arrow) and coudability sign (orange arrow)

Discussion

Globally, the incidence of AA varies from 0.57% to 3.8%.[3,8] In India, it is 0.7% according to a hospital-based study.[9] The mean age of onset of AA is in the fourth decade of life.[2] However, in BAA the onset of disease can occur over a wide range of ages.[6] In our study, it was 31.07 ± 8.72 years, which is in accordance with the mean age of 39.1 years as reported by Saceda-Corralo et al.[5] and other studies with lesser number of BAA cases.[10,11] It was also noted that 22 of 46 patients had active disease at the time of presentation, and statistically significant association was seen between active disease of BAA and extra-beard manifestation (P = 0.034). While there is a possibility of pathogenesis of BAA differing from that of AA, our observation further emphasizes the need to closely monitor these patients for development of new patches in other areas of the body.[6]

Irrespective of site of involvement, AA is known to be a chronically relapsing condition and hence, recurrence is often reported.[6,12] In our study, BAA recurrence was noted in 15.22% of patients, while Saceda-Corralo et al.[5] documented recurrence of BAA in 25.5% of their patients.

It is interesting to note that none of our patients had personal history of atopy or family history of AA. In a multicenter study done at Spain, Saceda-Corralo et al.[5] reported that 14.5% of the patients had some form of AA in their family, but none of our patients reported the same. In addition, none of our patients had a personal history of atopy. However, family history of atopy was noted in only 2.17% of the patients in this study.

AA is associated with an increased risk of development of other autoimmune conditions.[3,13,14] BAA, particularly, has been reported to be associated with asthma, atopic dermatitis, Crohn's disease, hyperparathyroidism, psoriasis, thyroid disease, and vitiligo.[5] Other case reports show evidence of a possible association of BAA with Helicobacter pylori infection,[15] hemochromatosis,[16] and primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma.[17] In our study, we noted systemic comorbid conditions such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus in three (6.52%) and one (0.17%) of the patients, respectively. In another study on 1137 Korean patients, it was found that 5.5% of subjects had hypertension and 2.5% had diabetes mellitus.[18] In yet another study, diabetes mellitus was found in 11.1% of patients with AA.[19]

Facial involvement is reported to be associated with depression, anxiety, and neurosis.[20] It is speculated that low quality of life and difficulty in coping with socialization due to visible nature of dermatological conditions could lead to habit of tobacco smoking and alcohol use.[21,22] Substance abuse like alcohol and smoking were noted in 13.04% and 10.84%, respectively, in our patients.

Extra-beard involvement of alopecic patches in BAA is a known phenomenon; it can either manifest concomitantly at the time of onset of BAA[6] or may occur anytime in future.[5] We noticed that 30.43% of our patients had concomitant involvement of sites other than beard, most commonly on the scalp followed by the eyebrow, eyelash, moustache, and limbs.

In a retrospective study, it was observed that 45.5% of the patients with BAA subsequently developed scalp AA which was recorded during follow-up.[5] In addition, AA was also seen to affect eyebrows and arms in their patients.[5]

Nail findings in exclusive BAA are uncommon.[6] However, nail changes like pitting, longitudinal striations, and longitudinal melanonychia detected in our study have already been previously described in AA.[23,24,25]

Dermoscopic findings in BAA such as black dots, short vellus hair, tapering hair, nonfollicular white dots, regrowing hair, yellow dots, and black dots were similar to findings noted in AA.[26,27,28,29] Uncommon findings such as peripilar sign, i-hair, perifollicular hemorrhage, and tulip hair were also noted.

While follicular microhemorrhage has been described as a diagnostic sign in TTM,[30] we observed this finding in one patient. Although a rare case of AA coexisting with TTM has been reported in a 6-year-old boy with a patch of hair loss in the occipital area,[31] such an association in our patient could have been unlikely for three reasons: (1) facial hair is the least likely site affected in TTM,[32] (2) presence of short vellus hair and tapering hair, and (3) absence of other characteristic dermoscopic features of TTM such as broken hair of different lengths and trichoptilosis.[32] We are of the opinion that this isolated finding of follicular hemorrhage in our patient could be due to facial hair grooming practice like shaving.

Peripilar sign, which was previously described only in lichen planus pigmentosus, was also seen in 17.39% of our patients. These are believed to represent perifollicular inflammation.[33] Interfollicular findings such as blotchy erythema, hem-like pigment pattern, and honeycomb pigment pattern were also seen in our study. Honeycomb pattern is reportedly common in chronic sun-exposed areas and scalp of dark-skinned individuals.[26,34] We surmise that the polarized filter of the dermoscope might have led to easier detection of these findings in our study. In addition, nonfollicular oriented white dots were seen in 30.43% of patients. These white dots could possibly represent the surface ductal openings of eccrine glands.[35]

Limitations of the study

This study is limited by its small sample size, lack of follow-up, and Fitzpatrick skin type of the patients. Our patients had only Fitzpatrick skin types IV and V. We did not actively investigate the patients for other systemic comorbidities.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, our study is the first single center study of the largest scale on male patients with BAA thus far. It is prudent to note that trichoscopy of BAA may perhaps reveal newer nonfollicular findings, in addition to the follicular findings already described in literature for AA. Hence, we recommend further studies in this regard.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hordinsky M, Ericson M. Autoimmunity: Alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:73–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2004.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villasante Fricke AC, Miteva M. Epidemiology and burden of alopecia areata: A systematic review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:397–403. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S53985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilhar A, Etzioni A, Paus R. Alopecia areata. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1515–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1103442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunt N, McHale S. Reported experiences of persons with alopecia areata. J Loss Trauma. 2004;10:33–50. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saceda-Corralo D, Grimalt R, Fernandez-Crehuet P, Clemente A, Bernardez C, Garcia-Hernandez MJ, et al. Beard alopecia areata: A multicentre review of 55 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:187–92. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cervantes J, Fertig RM, Maddy A, Tosti A. Alopecia areata of the beard: A review of the literature. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:789–96. doi: 10.1007/s40257-017-0297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain N, Doshi B, Khopkar U. Trichoscopy in alopecias: Diagnosis simplified. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:170–8. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.130385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan E, Tan YK, Goh CL, Chin Giam Y. The pattern and profile of alopecia areata in Singapore – A study of 219 Asians. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:748–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma VK, Dawn G, Kumar B. Profile of alopecia areata in Northern India. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:22–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1996.tb01610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emre S, Metin A, Caykoylu A, Akoglu G, Ceylan GG, Oztekin A, et al. Clinical characteristics and HLA alleles of a family with simultaneously occurring alopecia areata. Cutis. 2016;97:E30–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckert MMG, Gundin NL, Crespo RL. Alopecia areata: Good response to treatment with fractional laser in 5 cases. J Cosmetol Trichol. 2016;2:108. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Aggarwal A, Sethi G, Adhikari T. Alopecia areata in the Indian subcontinent. Skinmed. 2007;6:63–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.05652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller SA, Winkelmann RK. Alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:290–7. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1963.01590210048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas EA, Kadyan RS. Alopecia areata and autoimmunity: A clinical study. Indian J Dermatol. 2008;53:70–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.41650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campuzano-Maya G. Cure of alopecia areata after eradication of helicobacter pylori: A new association? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3165–70. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i26.3165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sredoja Tisma V, Bulimbasic S, Jaganjac M, Stjepandic M, Larma M. Progressive pigmented purpuric dermatitis and alopecia areata as unusual skin manifestations in recognizing hereditary hemochromatosis. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2012;20:181–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richmond HM, Lozano A, Jones D, Duvic M. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma associated with alopecia areata. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2008;8:121–4. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2008.n.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.You HR, Kim SJ. Factors associated with severity of alopecia areata. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:565–70. doi: 10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang KP, Mullangi S, Guo Y, Qureshi AA. Autoimmune, atopic, and mental health comorbid conditions associated with alopecia areata in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:789–94. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chu SY, Chen YJ, Tseng WC, Lin MW, Chen TJ, Hwang CY, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in patients with alopecia areata in Taiwan: A case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:525–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chodorowska G, Kwiatek J. Psoriasis and cigarette smoking. Ann Univ Mariae Curie Sklodowska Med. 2004;59:535–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asholan N, Priya P, Rejani PP. Severity of psoriasis among adult males is associated with smoking, not with alcohol use. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:237–40. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.131382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gandhi V, Baruah MC, Bhattacharya SN. Nail changes in alopecia areata: Incidence and pattern. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:114–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chelidze K, Lipner SR. Nail changes in alopecia areata: An update and review. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:776–83. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferreira SB, Scheinberg M, Steiner D, Steiner T, Bedin GL, Ferreira RB. Remarkable Improvement of nail changes in alopecia areata universalis with 10 months of treatment with tofacitinib: A case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2016;8:262–6. doi: 10.1159/000450848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross EK, Vincenzi C, Tosti A. Videodermoscopy in the evaluation of hair and scalp disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:799–806. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inui S, Nakajima T, Nakagawa K, Itami S. Clinical significance of dermoscopy in alopecia areata: Analysis of 300 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:688–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kibar M, Aktan Ş, Lebe B, Bilgin M. Trichoscopic findings in alopecia areata and their relation to disease activity, severity and clinical subtype in Turkish patients. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:e1–6. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mane M, Nath AK, Thappa DM. Utility of dermoscopy in alopecia areata. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:407–11. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.84768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ise M, Amagai M, Ohyama M. Follicular microhemorrhage: A unique dermoscopic sign for the detection of coexisting trichotillomania in alopecia areata. J Dermatol. 2014;41:518–20. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brzezinski P, Cywinska E, Chiriac A. Report of a rare case of alopecia areata coexisting with trichotillomania. Int J Trichol. 2016;8:32–4. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.179388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ankad BS, Naidu MV, Beergouder SL, Sujana L. Trichoscopy in trichotillomania: A useful diagnostic tool. Int J Trichol. 2014;6:160–3. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.142856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miteva M, Tosti A. Hair and scalp dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1040–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Moura LH, Duque-Estrada B, Abraham LS, Barcaui CB, Sodre CT. Dermoscopy findings of Alopecia areata in an African-American patient. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2008;2:52–4. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2008.1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rudnicka L, Rakowska A, Olszewska M. Trichoscopy: How it may help the clinician. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]