Abstract

Cytokinins are one of the most important phytohormones and play essential roles in multiple life processes in planta. Root-derived cytokinins are transported to the shoots via long-distance transport. The mechanisms of long-distance transport of root-derived cytokinins remain to be demonstrated. In this study, we report that OsABCG18, a half-size ATP-binding cassette transporter from rice (Oryza sativa L.), is essential for the long-distance transport of root-derived cytokinins. OsABCG18 encodes a plasma membrane protein and is primarily expressed in the vascular tissues of the root, stem, and leaf midribs. Cytokinin profiling, as well as [14C]trans-zeatin tracer, and xylem sap assays, demonstrated that the shootward transport of root-derived cytokinins was significantly suppressed in the osabcg18 mutants. Transport assays in tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) indicated that OsABCG18 exhibited efflux transport activities for various substrates of cytokinins. While the mutation reduced root-derived cytokinins in the shoot and grain yield, overexpression of OsABCG18 significantly increased cytokinins in the shoot and improved grain yield. The findings for OsABCG18 as a transporter for long-distance transport of cytokinin provide new insights into the cytokinin transport mechanism and a novel strategy to increase cytokinins in the shoot and promote grain yield.

Keywords: ABC transporter, cytokinin, efflux transporter, grain yield, long-distance translocation, rice (Oryza sativa L.)

OsABCG18 is essential for long-distance transport of cytokinins from root to shoot, and promotes grain yield in rice.

Introduction

Cytokinins are a class of N6-substituted adenine derivatives that were originally discovered by C. Miller, F. Skoog, and co-workers during the 1950s as factors that promote plant cell division (Miller et al., 1955; Amasino, 2005). According to their side chain structure, natural cytokinins are divided into isoprenoid and aromatic cytokinins (Sakakibara, 2006). The structure and conformation of the N6-attached side chain can markedly influence the biological activity of cytokinins (Schmülling, 2004; Kiba et al., 2013). The common cytokinins in higher plants that have been intensively studied include N6-(Δ 2-isopentenyl) adenine (iP), trans-zeatin (tZ), dihydrozeatin (DHZ), and cis-zeatin (cZ), with diverse variations depending on the plant species (Sakakibara, 2006). For >60 years, cytokinins have been proven to be tightly involved in a broad range of plant life processes, including the regulation of root and shoot apical dominance (Matsumoto-Kitano et al., 2008), leaf senescence (Gan and Amasino, 1995), chloroplast development (Chory et al., 1994), the formation of nitrogen-fixing nodules (Sasaki et al., 2014), immunity (Choi et al., 2010), the sink–source relationship, and stress responses (Sakakibara, 2006; Rivero et al., 2007; Werner et al., 2010).

The metabolism and signal transduction of cytokinins have been well studied (Sakakibara, 2006; Frebort et al., 2011; Hwang et al., 2012; Jameson and Song, 2016). The biosynthesis and catabolism of cytokinins are processed by a series of enzymes including cytokinin biosynthesis by IPT (Kakimoto, 2001; Takei et al., 2001), activation by LOG (Kurakawa et al., 2007), irreversible degradation by CKX (Galuszka et al., 2001; Werner et al., 2003), reversible inactivation by ZOG, and trans-hydroxylation by CYP735A1 and CYP735A2 (Kiba et al., 2013). The spatial expression patterns of the biosynthetic and catabolic genes indicate that cytokinins can be locally synthesized in both the shoot and root and act as autocrine, paracrine, or long-distance transport signals (Hirose et al., 2008; Matsumoto-Kitano et al., 2008). Transcriptional metabolite analysis and grafting studies have suggested that tZ-type cytokinins are primarily synthesized in the roots while iP-type cytokinins are largely synthesized in the shoots of Arabidopsis (Matsumoto-Kitano et al., 2008; Kiba et al., 2013). Cytokinin signaling comprises a two-component pathway which triggers the signaling responses (Hwang et al., 2012). It has been demonstrated that each receptor has a different binding affinity for cytokinins with different side chains (Romanov et al., 2006; Choi et al., 2012; Kiba et al., 2013); thus, the functions of different cytokinin derivatives may be diverse and require investigation.

De novo cytokinin biosynthesis occurs only in some specific cell types; cytokinins have to be delivered to the target cells for signaling by autocrine, paracrine, and/or long-distance translocation (Kang et al., 2017; Romanov et al., 2018). In contrast to the well-established transport mechanisms of auxin (Robert and Friml, 2009), the molecular basis of cytokinin transport has not yet been thoroughly investigated. It has been suggested that root-derived cytokinins were loaded in the xylem as tZ and tZ riboside (tZR), and exported to the shoot by the respiration stream to regulate shoot development in Arabidopsis (Aloni et al., 2005). Alternatively, shoot-derived cytokinins were transported to the root as iP or iP riboside (iPR) through the phloem to regulate root development or root nodulation (Bishopp et al., 2011; Sasaki et al., 2014). Currently, ENT (equilibrative nucleotide), PUP (purine permease), and ABCG (ATP-binding cassette G) are three transporter families known to be involved in cytokinin transport in Arabidopsis and rice (Sun et al., 2005; Ko et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014; Zurcher et al., 2016). AtABCG14 has been identified as a long-distance transporter (Ko et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014) that is responsible for the transport of tZ-type cytokinins from root to shoot, but which cytokinins among many are transported by AtABCG14 and whether AtABCG14 overexpression can accelerate shootward transport of cytokinins remain to be investigated.

Rice is a major staple crop for >3.5 billion people worldwide and is also a monocot model plant. Cytokinin is one of the most important hormones in the molecular breeding of rice (Li et al., 2013; Jameson and Song, 2016). Mutation of OsCKX2/Gn1a significantly improved the rice grain yield by ~20% (Ashikari et al., 2005), and knockdown lines were subsequently shown to produce more tillers and grains per plant and to exhibit a heavier 1000-grain weight (Yeh et al., 2015). The DST transcription factor is the regulator of OsCKX2, and the corresponding mutant shows a significantly improved crop yield (Li et al., 2013). The cytokinin signal transduction components and the cytokinin-inducible transcriptome in rice have been analyzed (Hill et al., 2013; Raines et al., 2016; Daudu et al., 2017).The OsENT2, OsPUP7, and OsPUP4 transporters in rice have been shown to have functions that are directly related to cytokinins in vitro or in vivo (Hirose et al., 2005; Qi and Xiong, 2013; Xiao et al., 2019), but the understanding of cytokinin transport mechanisms and their potential application in rice remains poor.

To elucidate the long-distance transport of root-derived cytokinins and to investigate its function in crop productivity, characterization and functional analysis of the cytokinin transporter in rice are essential. Here we characterized OsABCG18 as a long-distance transporter for shootward transport of cytokinins in rice. The osabcg18 mutant displayed multiple defects in essential agronomic traits, resulting in a reduction of grain yield, while overexpression of OsABCG18 improved grain yield. Hormone profiling, [14C]tZ uptake, and xylem sap assay demonstrated that OsABCG18 was involved in root to shoot transport of tZ-type cytokinins in rice. Our results provide new insights into the shootward transport of root-derived cytokinins and elucidate their essential roles in molecular breeding.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth condition

Oryza sativa L. ssp. Japonica or Keng (cv. Nipponbare; NIP) and ssp. Japonica or Keng (cv. Zhonghua 11; ZH11) were used as the wild type. For hydroponic growth, the seeds were soaked in water for 2 d at 28 °C in the dark, transferred to net gauze for 1 d at 35 °C in the dark, and moved into the light. Ten-day-old seedlings were transferred to a 7 liter plastic pot containing the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) nutrient solution (Yoshida et al., 1976). In the field experiments, the wild-type, mutant, or overexpression lines were grown in a muddy field from May to October in 2016–2018 in Jinhua, China.

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) was grown following a method described previously (Zhang et al., 2014). Tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) was sown in the soil and grown in a growth chamber with 120 μmol m–2 s–1 light intensity, 50% relative humidity, and a 12 h/12 h day/night regime at 28 °C.

Phylogenic analyses

Phylogenetic analyses were performed using MEGA6 as described previously (Tamura et al., 2013). The full-length ABCG protein sequences were retrieved from TAIR (The Arabidopsis Information Resource; http://www.arabidopsis.org/) and RGAP (Rice Genome Annotation Project; http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/) and used for the phylogenetic analyses. Multiple sequence alignments were conducted using Clustal Omega in EBI (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) with the PAM matrix. A Neighbor–Joining (NJ) tree was built using MEGA6 adopting Poisson correction distance and was presented using circle tree view. Support for the tree obtained was assessed using the bootstrap method with 1000 replicates. The Arabidopsis and rice ABCG family was named as described by Matsuda et al. (2012).

Hormone treatments

For gene-inducible expression assay, the hormone treatments were applied as previously described (Matsuda et al., 2012). The roots of seedlings at 10 days after germination (DAG) were incubated in IRRI solution containing 1 μM cytokinins [tZ, iP, cZ, and 6-benzyladenine (6-BA)] or 20 μM indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) at 30 °C for 2 h. The roots were collected for RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR).

For the phenotype rescuing experiment of osabcg18, the 15 DAG seedlings grown in IRRI solution were sprayed daily with 20 μM tZ, 20 μM iP, or 0.5% methanol (control) at it means 10 o’clock in the morning, so please correct it to 10 a.m. The plant height and fresh weight were measured 25 d after cytokinin treatment.

Plasmid construction, gene cloning, and gene transformation

To generate construct OsABCG18Pro::GUS, a 3266 bp promoter region of OsABCG18 was amplified by the primers OsABCG18-P3/P4 and cloned into pCAMBIA1301 by replacing the 35Spro. The coding region of OsABCG18 was amplified using the primers OsABCG18-P1/P2 and cloned into pSAT6-35S::EGFP and pSAT6-ABCG18Pro::EGFP, and then into the pRCS2 vector to form constructs 35S::EGFP-ABCG18 and OsABCG18Pro::EGFP-ABCG18.

The clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/CRISPR-assocated protein 9 (Cas9) vectors used to create osabcg18 were constructed as previously described (Xie and Yang, 2013). Two target guide RNA (gRNA) sequences of OsABCG18 were designed at the Crispr-plant website (http://www.genome.arizona.edu/crispr/), and the primers were G18CAS1F, R and G18CAS2F, R. The gRNAs were respectively inserted into the pRGEB31 vector (Xie and Yang, 2013) digested with BsaI to generate binary construct gRNA-pRGEB31. The binary vectors were transformed into Agrobacterium GV3101 and transformed into rice using an agrobacterial method or to into Arabidopsis using the floral dip method. All the primers used in this work are shown in Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online.

GUS expression and histochemical analysis

β-Glucuronidase (GUS) staining was performed as previously described (Jefferson et al., 1987) with minor modifications. For sectioning, the plant tissues were fixed using formalin–acetic acid–alcohol (1.8% formalin, 5% acetic acid, and 90% methanol) and embedded in paraffin. Sections 7 μm (leaf and root) and 15 μm (stem) thick were cut to observe the vascular expression.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Various tissues including roots, stems, and young and mature leaves were harvested at the booting stage (~70 DAG) for RNA extraction. Young panicles and filling stage panicles of 12 cm and 18 cm in length, respectively, were harvested for RNA extraction. Total RNA was prepared using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized using HiScript QRTsupermix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) (R123-01,Vazyme, China). qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green (TaKaRa) on an ABI PRISM 7700 system (Applied Biosystems, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For qRT-PCR, the OsABCG18 primers ABCG18-P5/-P6 were used, and the ubiquitin (UBQ) gene amplified with UBQ-F/-R was used for quantitative normalization.

Subcellular localization and immunoblot analysis

Tobacco transient expression was performed as previously described (Sparkes et al., 2006). Briefly, the tobacco leaves were transformed with EGFP–OsABCG18 and the plasma membrane marker CBL–mCherry mediated by GV3101. Rice seedlings at 10 DAG expressing ABCG18pro::EGFP-ABCG18 were used for protein subcellular localization. Images were captured using a Leica TCS SP5 microscope following a method described previously (Zhang et al., 2014). The immunoblot analysis was performed following the method described previously (Zhang et al., 2014).

[14C]trans-zeatin tracer experiment

The [14C]tZ tracer experiment was performed as previously described (Zhang et al., 2014). The root tips of osabcg18 and wild-type seedlings at 10 DAG were immersed in 5 mM MES-KOH (pH 5.6) buffer containing [14C]tZ (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, 3700 Bq ml–1, final concentration 5 nM). After 20 h incubation, the roots and shoots of the seedlings were carefully separated using a razor blade at the junction between the roots and the shoots. The shoots and the roots from three seedlings of each genotype were separately pooled as replicates. The roots were washed again three times with 10 ml of 5 mM MES-KOH (pH 5.6) buffer. The samples were mixed with 1.5 ml of bleach and incubated at 70 °C for 3 h to solubilize the tissues. The radioactivity of the supernatant was quantified by a scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter LS6500).

Hormone profiling

The cytokinin or ABA extraction followed a method previously described (Cao et al., 2015). A 100 mg aliquot of ground tissues was mixed with 1 ml of 80% methanol with internal standards (45 pg of 2H5-tZ, 2H5-tZR, 2H6-iP, 2H6-iPR and 100 pg of [2H6]ABA), and subsequently extracted twice using a laboratory rotator for 2 h at 4 °C. After centrifugation (10 min, 15 000 g, and 4 °C), the supernatant was collected and dried by nitrogen gas. Then the pellet was resolved in 300 μl of 30% methanol and filtrated though a filter membrane (0.22 μm).

The cytokinins or ABA were separated by Exion LC (AB SCIEX) equipped with an Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1×100 mm, particle size of 1.7 µm). The column was maintained at 40 °C and the mobile phases for cytokinins were composed of water (A) and MeOH (B) using a multistep linear gradient elution: 5% B at 0–2.5 min, 5–20% B at 2.5–3 min, 20–50% B at 3–12.5 min, 50–100% B at 12.5–13 min, 100% B at 13–15 min, 100–5% B at 15–15.2 min, and 5% B at 15.2–18 min. The mobile phases for ABA were composed of water (A) with 0.1% formic acid and MeOH (B) with 0.1% formic acid using a multi-step linear gradient elution: 20% B at 0 to 1 min, 20 to 100% B at 1 to 7 min, 100% B at 7 to 9 min, 100 to 20% B at 9 to 9.3 min and 20% B at 9.3 to 12 min. The flow rate was 0.3 mL min−1.

The cytokinins or ABA were analyzed by the triple quadruple mass spectrometer QTRAP 5500 system (AB SCIEX) following a method previously described (Simura et al., 2018). The optimized conditions were as follows: curtain gas, 40 psi; ion spray voltage, 5000 V for positive ion mode or –4500 V for negative ion mode; turbo heater temperature (Hellens et al., 2005), 600 °C; nebulizing gas (Gas 1), 60 psi; heated gas (Gas 2), 60 psi. Analyst software (version1.6.3, AB SCIEX) was used. The data analysis was processed by MultiQuant software (version3.0.2, AB SCIEX). Cytokinins or ABA were accurately quantified through the internal standards.

Xylem sap analysis

Xylem sap was collected as described previously (Ma et al., 2004) with minor modifications. The shoots (1 cm above the roots) of 30-day-old seedlings grown in IRRI solution were excised using a blade. The xylem sap was collected, except for the first drop, using a micropipette for 3 h after decapitation of the shoot. The total cytokinin contents in the sap was extracted and measured following the methods described above.

Assays of transport activity using a tobacco transient expression system

The young tobacco leaves were injected with Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 harboring 35S::EGFP-ABCG18 and empty vector. Protein expression was examined 72 h following the injection before the transport activity assay. The leaves were cut into 3 mm×3 mm squares and 0.1 g was taken for each sample. Samples were washed twice with efflux buffer [5 mM MES-KOH buffer (pH 5.7)], with or without 1 mM sodium vanadate. Four samples were set for extracting cytokinins/abscisic acid (ABA), and the other four samples were incubated in efflux buffer (with or without 1 mM sodium vanadate) at 22 °C for 0, 10, 20, 40, 60, and 90 min. Extracts of 30 μl were used for cytokinin and ABA quantification by LC-MS.

For transport activity assay in protoplasts, the protoplasts were prepared from tobacco discs as previously described (Yoo et al., 2007). The protoplasts were washed once and then were resuspended in W5 solution and kept on ice for 30 min. After being washed twice again with W5 solution, 2–4×104 protoplasts were incubated in W5 solution (0.8 ml) with or without 1 mM sodium vanadate at 22 °C . Aliquots of 200 μl were collected from the efflux buffer at time points of 0, 5, 20, and 40 min for hormone quantification by LC-MS following the method described above.

Analysis of agronomic traits

The agronomic traits including plant height, seed number per panicle, seed-setting rate, tiller number per plant, and grain yield per plant were measured on a single-plant basis. To measure the grain size, ~150 rice grains from each plant were photographed using a high-speed photographic apparatus (Eloam, Shenzhen, China). More than 10 plants of each line were used for photography. The images were processed using SC-G software (Hangzhou Wanshen Detection Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China, www.wseen.com). To image the grains, 20 grains were spread on the glass plate of a flatbed scanner (Microtek i600, Shanghai, China). The scanner was set in the reflection imaging mode, RGB color, and 600 dpi. The images were processed using SC-G software. For the comparisons between two groups of data, the two-tailed Student’s t-test was used.

Accession codes

The genes and their associated accession codes are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Results

Phylogenic analysis and gene expression patterns of OsABCG18

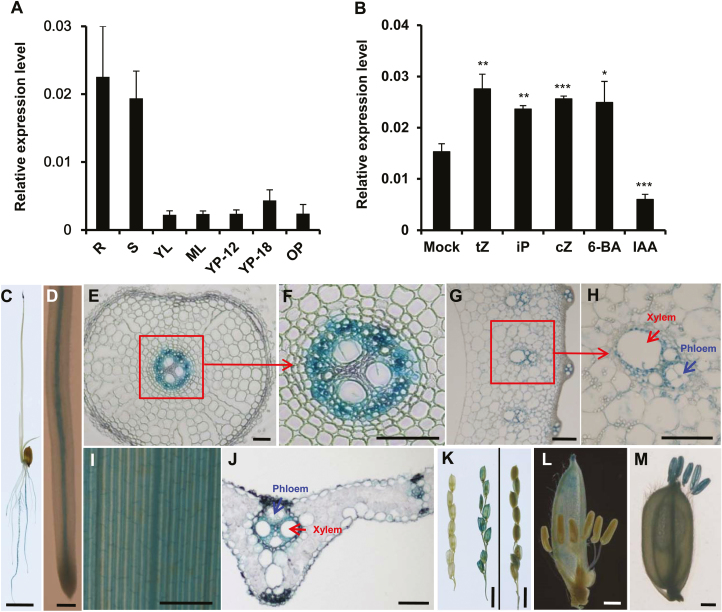

To study the transport and physiological functions of tZ-type cytokinin in rice, we prepared the phylogenic tree of the half-size ABC transporter G subfamily from rice and Arabidopsis with MEGA6 software using the NJ method (see Supplementary Fig. S1). OsABCG18 was found to be the closest ortholog to AtABCG14 in the phylogenetic tree (Supplementary Fig. S1). The expression of OsABCG18 in different tissues of rice, namely roots, stems, young leaves, old leaves, and panicles at different stages, was quantified using qRT-PCR. OsABCG18 showed high expression in roots and stems and low expression in leaves and panicles (Fig. 1A). As previously reported, the expression of some transporter genes was induced by their substrates (Jasinski et al., 2001; Ko et al., 2014; Pierman et al., 2017). We examined the expression of OsABCG18 under cytokinin treatments (tZ, iP, cZ, and 6-BA), and found that OsABCG18 was specifically induced by cytokinins (Fig. 1B), suggesting its involvement in cytokinin transport. In addition, the expression of OsABCG18 was dramatically suppressed by IAA (Fig. 1B), suggesting that it may play an essential role in the interplay between cytokinins and auxin in rice.

Fig. 1.

The expression patterns of OsABCG18 in various tissues and in response to different hormone treatments. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of OsABCG18 expression in different tissues of rice. R, root; S, stem; YL, young leaves; OL, old leaves; YP-12, 12 cm length young panicle; YP-18, 18 cm long young panicle; and OP, panicle at the filling stage. Data are means ±SD (n=3). (B) Relative expression of OsABCG18 in rice seedlings treated with different types of cytokinins (tZ, iP, cZ, and 6-BA) and the auxin IAA. Mock indicates the mock treatment as detailed in the Materials and methods. (C) GUS staining of seedlings at 10 DAG of OsABCG18pro::GUS transgenic plants, indicating that the GUS gene was primarily expressed in the root and shoot tip. Scale bar=1 cm. (D) Enlarged image of the primary root of the seedlings in (C). Scale bar=100 μm. (E and F) Semi-thin section of the primary root of the seedlings at 10 DAG. Scale bar=20 μm. (G and H) Paraffin section of the stem of adult OsABCG18pro::GUS transgenic plants. Scale bar=100 μm. (I) GUS staining of leaves from adult OsABCG18pro::GUS transgenic plants, indicating that the GUS gene was primarily expressed in the midribs. Scale bars=1 mm. (J) Semi-thin section of the leaves in (I). Scale bar=20 μm. (K) Primary branch of the 12 cm panicle (left), primary branch of the 18 cm panicle (middle), and primary branch of the panicle at the filling stage (right). Scale bar=1 cm. (L) Immature stamen. Scale bar=1 mm. (M) Mature stamen. Scale bar=1 mm. The red and blue arrows indicate the xylem and phloem, respectively. Data are means ±SD (n=3). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 (Student’s t-test).

To address the tissue-specific expression of OsABCG18 in rice, we fused OsABCG18Pro, a 3.3 kb promoter region of OsABCG18, to the GUS reporter gene and transformed it into rice. GUS staining of young seedlings of the representative OsABCG18Pro::GUS transgenic plants shows that OsABCG18 was primarily expressed in roots (Fig. 1C). The enlarged image of the primary root showed that OsABCG18 was preferentially expressed in the stele of the root (Fig. 1D) and mid-rib of leaves (Fig. 1I). Semi-thin and paraffin sections of the roots revealed its expression in cells of the pericycle and stele of the roots (Fig. 1E, F), and cells in the phloem and xylem of the stems and leaf midribs (Fig. 1G, H, J). GUS staining of panicles and stamens at different stages demonstrated that OsABCG18 was highly expressed in the 18 cm stage (Fig. 1K) and mature stamens (Fig. 1L, M).

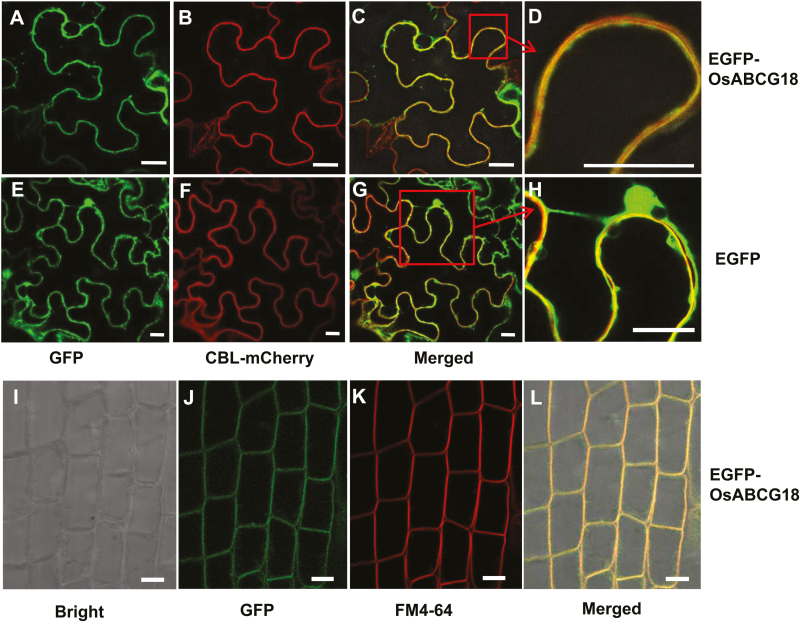

OsABCG18 is a plasma membrane protein

The subcellular location of a transporter determines its transport properties. To further elucidate the physiological function of OsABCG18, we fused enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) to the N-terminus of OsABCG18 and determined the subcellular location of the EGFP–OsABCG18 fusion protein using transient expression in tobacco with free GFP as a control. The localization of GFP–OsABCG18 was visible in the plasma membrane in the tobacco leaf epidermis cell, and it was co-localized with a plasma membrane marker (Fig. 2A–D), CBL1n–mCherry (Batistic et al., 2008), but the free GFP did not co-localize with CBL1n–mCherry (Fig. 2E–H), clearly demonstrating its localization in the plasma membrane. We further checked the location of GFP–OsABCG18 in the stable transgenic plants of rice. When the OsABCG18pro::EGFP-OsABCG18 cassette was stably expressed in wild-type rice, the fluorescence distribution of the fusion protein in root cells agreed well with that revealed by staining with FM4-64 (Fig. 2I–L), a typical plasma membrane indicator (McFarlane et al., 2010).

Fig. 2.

Subcellular localization of the GFP–OsABCG18 fusion protein. Green fluorescence distribution when 35S::EGFP-OsABCG18 (A) or 35S::EGFP (E) was transiently expressed in tobacco leaf epidermal cells; red fluorescence distribution of the plasma membrane marker CBL–mCherry (B) and (F) and their merged images with (A) and (E) as (C) and (G). (D) An enlarged image of (C), which indicates that EGFP–OsABCG18 was completely merged with the plasma membrane marker CBL–mCherry, but the negative control EGFP was only partially merged with CBL–mCherry (G and H). Scale bar=20 µm. (I–L) The fluorescence distribution in the root tip region of OsABCG18pro::EGFP-OsABCG18 transgenic rice; the DIC image of the root (I), green florescence of EGFP–OsABCG18 (J), and red florescence of FM4-64 (K) are merged in (L). Scale bars=20 µm. The roots were stained with 10 mM FM4-64 (Molecular Probes) for 10–30 min.

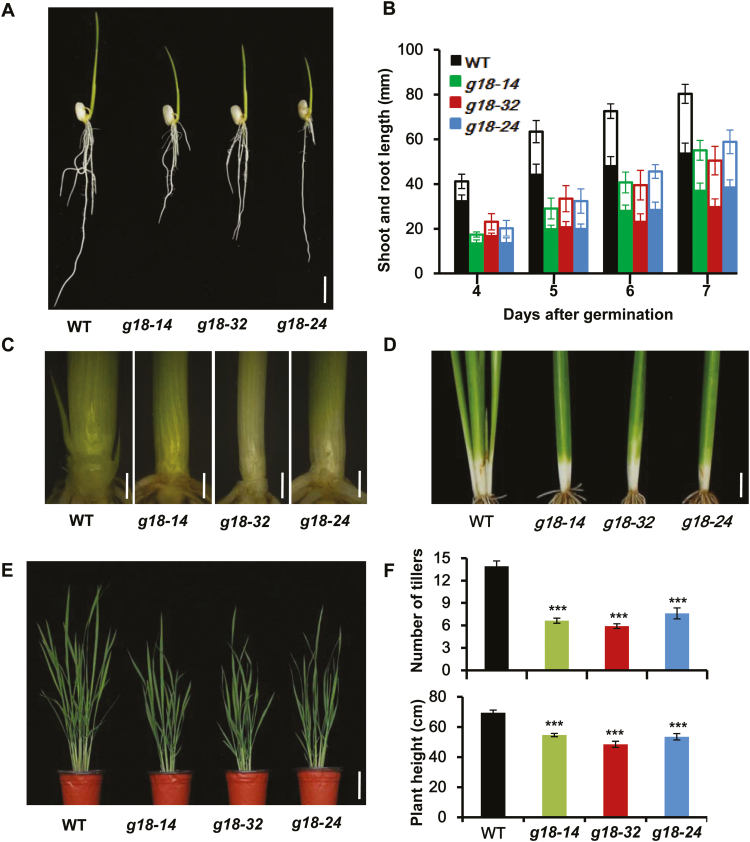

osabcg18 displays defects in growth and tiller emergence in the vegetative stage

To identify the biological function of OsABCG18 in rice, loss-of-function mutants of OsABCG18 were created using the CRISPR/Cas9 system (Xie and Yang, 2013). One gRNA targeting base pairs 305–324 of the coding sequence (CDS) close to the start codon and an additional gRNA target in the transmembrane domain (base pairs 1598–1617 of the CDS) were selected for gene editing (Supplementary Fig. S2A). Seven independent homozygous frameshift mutant lines were confirmed by gene sequencing, in which four different mutant lines were identified in the first gRNA target and three different lines were identified in the second gRNA target (Supplementary Fig. S2B). The homozygous lines of osabcg18 all displayed a dwarf phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S2C).

Three representative lines (osabcg18-14, osabcg18-32, and osabcg18-24) were chosen for further study. The shoot and root growth of the young seedlings were measured from 4 to 7 DAG, and the shoots and roots were reduced up to 28.2% and 44.5% at 7 DAG, respectively (Fig. 3A, B). As shown in the plants at 20 DAG, tiller buds were initiated in the wild type but not in osabcg18 at this time (Fig. 3C, D), indicating that the tiller emergence was delayed in osabcg18 compared with the wild type. At 55 DAG, the average tiller number was significantly reduced in osabcg18 compared with the wild type (6.7±0.9 versus 13.9±2.9, respectively) (Fig. 3E, F). The average plant height of osabcg18 was 52.2±3.3 cm, which was significantly decreased compared with the height of the wild type at 69.4±7.4 cm (Fig. 3E, F). The growth defects in osabcg18 showed that OsABCG18 was critical for the growth and development of rice in the vegetative stage.

Fig. 3.

Morphological phenotype of osabcg18 mutant lines in the vegetative stage. (A) Phenotype of seedlings at 7 DAG of the wild type and osabcg18 mutant lines g18-14, g18-32, and g18-24. Scale bar=1 cm. (B) Growth of the shoot (unfilled column) and root (filled column) was significantly delayed, as calculated from 4 to 7 DAG. Data are means ±SD (n=15). (C) The peeled shoot bases of wild type and osabcg18 mutant lines at 20 DAG. The wild type generated tiller buds that initiated in mutants but had not emerged at the time. Scale bar=1 mm. (D) Shoot bases of the wild type and osabcg18 mutant lines at 35 DAG. The wild type generated a few tillers that were invisible in the mutants. Scale bar=1 cm. (E) Phenotype of the wild type and osabcg18 mutant at 55DAG. Scale bars=10 cm. (F) Quantification of the tiller number and plant height in the osabcg18 mutant and wild type in (E). Data are means ±SD (n≥10). ***P<0.001 (Student’s t-test).

To determine whether the growth defects in the shoot were caused by the shortage of tZ- or iP-type cytokinins, we subjected the mutants to mock, tZ, or iP treatment and found that only tZ rescued the dwarf and small phenotype of osabcg18 to wild type (Supplementary Fig. S3A–C). The shoot height and fresh weight of osabcg18 treated with tZ were rescued to wild type, but the mutant treated with iP was not rescued (Supplementary Fig. S3D, E), indicating that the shortage of tZ-type cytokinin in the shoot was mainly responsible for the growth defects.

To determine whether OsABCG18 had the same biological or biochemical functions as AtABCG14, we constructed binary vectors expressing OsABCG18 using the 35SPro or native promoter OsABCG18Pro and transformed them into atabcg14 to examine the functions of OsABCG18 (Supplementary Fig. S4). As expected, both OsABCG18Pro::ABCG18 and 35S::ABCG18 successfully complemented the phenotypes of atabcg14 (Supplementary Fig. S4), suggesting that OsABCG18 plays parallel roles to AtABCG14 in Arabidopsis.

Root-derived cytokinins are reduced in the shoot but overaccumulated in the root of osabcg18

As previously shown, the retarded growth of osabcg18 was caused by the shortage of tZ-type cytokinins in the shoot. To examine the gene expression of the cytokinin-responsive genes in osabcg18, we examined the expression of OsRR genes in the roots and shoots of rice. The typical cytokinin-responsive genes OsRR2, 6, and 10 (Tsai et al., 2012) were selected as representative genes to indicate the concentration of cytokinins in the tissues. The qRT-PCR results showed that the expression levels of OsRR2, 6, and 10 were all reduced in shoots (Supplementary Fig. S5A) and OsRR2 and 6 were enhanced in the roots of osabcg18 (Supplementary Fig. S5B), indicating that cytokinins might be reduced in the shoots but were overaccumulated in the roots of osabcg18 compared with the wild type.

To further understand the distribution of cytokinins in the roots and shoots of osabcg18, we performed hormone profiling in osabcg18 and the wild type. The roots and shoots of the wild type and osabcg18 lines 14 and 32 grown in soil were harvested for cytokinin quantification using LC-MS (Table 1). tZ, tZR, and DHZ were increased up to 3.5-, 4.8-, and 3.9-fold, respectively, in roots and reduced to <57, <53, and <35%, respectively, in shoots of mutants compared with the wild type. The iP- and cZ-type cytokinins were significantly increased in roots but only slightly decreased in shoots of osabcg18 compared with the wild type (Table 1), suggesting that the biosynthesis and transport of those cytokinins might be indirectly affected by the absence of OsABCG18.

Table 1.

Cytokinin contents (pmol g–1 FW) in the roots and shoots of the wild type (WT) and osabcg18 mutantsa

| CKs | WT shoot | osabcg18-14 shoot | osabcg18-32 shoot | WT root | osabcg18-14 root | osabcg18-32 root |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tZ | 2.12±0.32 | 1.22±0.05** | 1.27±0.26** | 0.57±0.35 | 2.02±0.47** | 1.23±0.12* |

| tZR | 0.29±0.14 | 0.16±0.01* | 0.20±0.04* | 0.38±0.17 | 1.20±0.37** | 1.43±0.31** |

| DHZ | 0.10±0.01 | 0.04±0.01** | 0.05±0.01** | 0.07±0.02 | 0.28±0.03** | 0.15±0.01** |

| iP | 0.24±0.14 | 0.55±0.11* | 0.41±0.05* | 0.21±0.09 | 0.11±0.02 | 0.16±0.01 |

| iPR | 0.32±0.18 | 0.22±0.03 | 0.20±0.03 | 0.28±0.18 | 0.66±0.04** | 0.55±0.06** |

| cZ | 1.08±0.37 | 0.82±0.23 | 0.95±0.24 | 0.78±0.08 | 1.58±0.20** | 1.27±0.14** |

| cZR | 0.66±0.14 | 0.63±0.10 | 0.61±0.03 | 0.69±0.11 | 0.85±0.07 | 0.77±0.07 |

a The roots and shoots of plants grown in the field for 50 d were collected for cytokinin quantification.

Data are means ±SD (n=4), * and ** indicate significant differences at P<0.05 and P<0.01, respectively, from Student’s t-test.

CK, cytokinin; tZ, trans-zeatin; tZR, trans-zeatin riboside; DHZ, dihydrozeatin; iP, isopentenyladenine; iPR, isopentenyladenosine; cZ, cis-zeatin; cZR, cis-zeatin riboside.

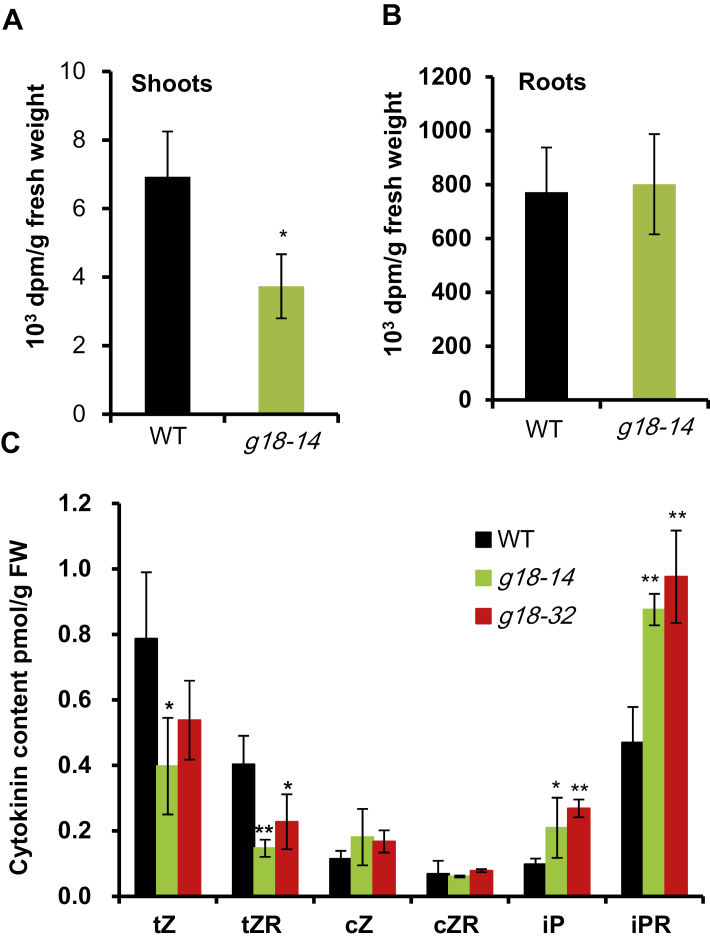

Root to shoot transport of tZ-type cytokinins is directly suppressed in osabcg18

The expression patterns of the cytokinin-responsive genes, together with the overaccumulation of cytokinins in the root and reduction in the shoot, suggested that OsABCG18 could function as a transporter responsible for the root to shoot transport of cytokinins. To further investigate the role of OsABCG18 in the transport of tZ-type cytokinins from root to shoot, isotopic tracing experiments were performed to follow the transport of tZ (Fig. 4A, B). The roots of the wild type and osabcg18 line g18-14 were immersed in an MES-KOH (pH 5.8) solution containing [14C]tZ for 20 h, and the [14C]tZ exported from roots to shoots of osabcg18 and the wild type were measured. The results showed that [14C]tZ accumulation in the root did not differ between the wild type and mutant (Fig. 4B); however, the radioactivity of [14C]tZ was significantly decreased in the shoot of osabcg18 to 46% of that in the wild type (Fig. 4A). Therefore, OsABCG18 was hypothesized to be directly involved in root to shoot transport of tZ-type cytokinins.

Fig. 4.

[14C]tZ tracer experiment and xylem sap assays in the wild type and osabcg18 mutant. Radioactivity in shoots (A) and roots (B) of the wild type and osabcg18 mutant 20 h after feeding [14C]tZ to the roots. Seedlings grown in hydroponic conditions were used. The transport of exogenously applied [14C]tZ from roots to shoots was significantly suppressed in osabcg18 mutant. Data are means ±SD (n=5). (C) Cytokinin profiling in xylem sap from the wild type and osabcg18 mutants. tZ, tZR, cZ, cZR, iP, and iPR were measured. Data are means ±SD (n=3). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 (t-test in one-way ANOVA). tZ, trans-zeatin; tZR, trans-zeatin riboside; cZ, cis-zeatin; cZR, cis-zeatin riboside; iP, isopentenyladenine; iPR, isopentenyladenosine.

To further understand the potential substrates of OsABCG18, we collected the xylem sap from seedlings grown in hydroponic conditions (Fig. 4C). We detected tZ-, cZ-, and iP-type cytokinins in the xylem sap and found that all three types of cytokinins could be exported from the root to the shoot through the xylem vessels. tZ and tZR were significantly reduced up to 59% and 47%, respectively, in the xylem sap from osabcg18 compared with the wild type (Fig. 4C). This reduction rate was consistent with the cytokinin quantification in the shoot (Table 1). The cZ-type cytokinins did not show any significant difference in the xylem sap. Interestingly, the iP-type cytokinins increased 1-fold in the sap, consistent with the overaccumulated iP-type in the root of osabcg18 (Table 1), suggesting that the iP-type cytokinins were increased in response to the accumulation of tZ-type cytokinins in the root of osabcg18.

OsABCG18 mediated the efflux transport of various cytokinins

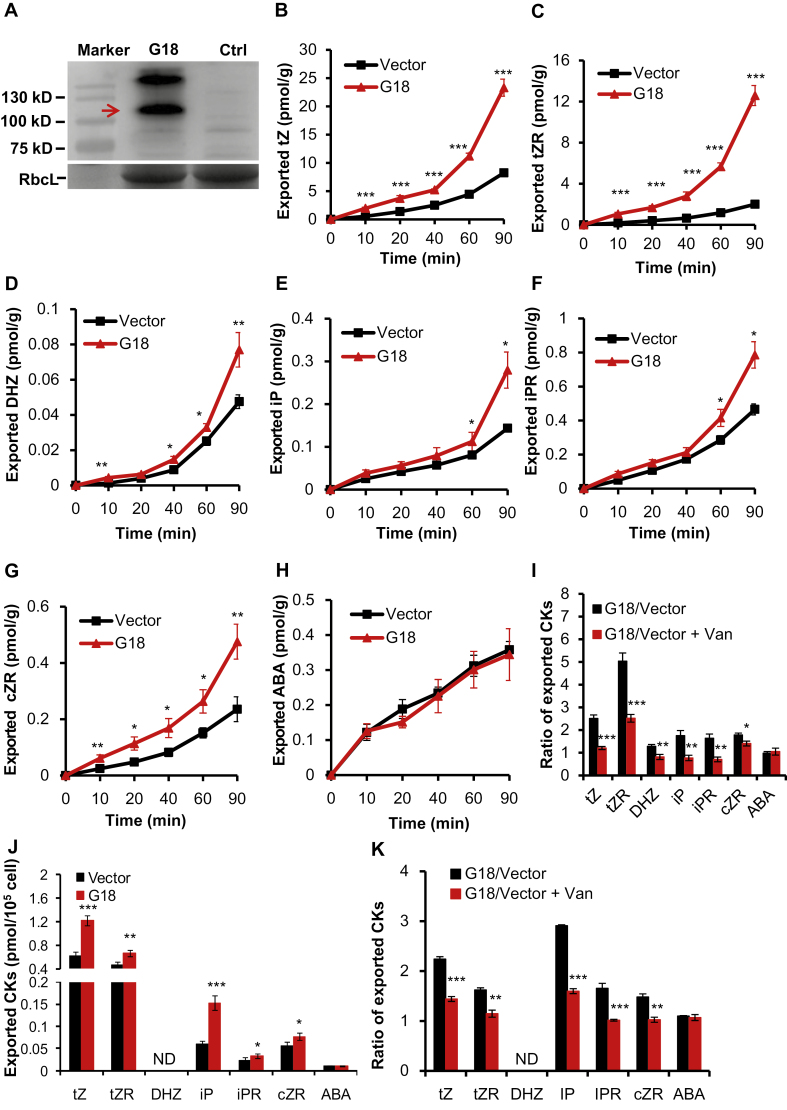

Since the accumulation of 14C-labeled tZ was significantly reduced in the detached leaves expressing AtABCG14, AtABCG14 was suggested to be an exporter for tZ (Zhang et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2019). However, the clear substrates of AtABCG14 remain to be investigated. As previous data have indicated that OsABCG18 is a functional ortholog of AtABCG14, we aimed to explore the substrate of OsABCG18 to elucidate the substrates of these types of transporters. We transiently expressed the empty vector (free GFP) and 35S::EGFP-OsABCG18 in tobacco leaves, and the expression of free GFP and EGFP–ABCG18 was observed by confocal microscopy and detected by western blotting (Fig. 5A; Supplementary Fig. S6A, B). The leaf discs with EGFP–ABCG18 or empty vector were harvested, cut into equal pieces, and washed with efflux solution. The leaf pieces were incubated in the uptake buffer, and the cytokinin/ABA exported to the efflux solution was collected from 0 min to 90 min and measured by LC-MS. Compared with the empty vector control, tZ, tZR, DHZ, iP, iPR, and cZR levels were significantly higher in the efflux solution with EGFP–ABCG18 at different time points (Fig. 5B–H), indicating that OsABCG18 exhibited transport activities for cytokinins. Moreover, the ABA content exported to the efflux solution was similar with OsABCG18 to the empty vector, validating the specificity of the efflux transport activities of OsABCG18 on tZ, tZR, DHZ, iP, iPR, and cZR. To further validate the transporter activities and directionality, we prepared protoplasts from tobacco leaf discs transformed with EGFP–ABCG18 or empty vector, and the exported cytokinins were quantified by LC-MS at 0 min to 40 min. Although DHZ was not detected due to its low concentration, tZ, tZR, iP, iPR, and cZR all displayed results consistent with the assays with leaf discs (Fig. 5J; Supplementary Fig. S7).

Fig. 5.

OsABCG18 mediated efflux transport of various cytokinins in tobacco. (A) Immunoblot analysis of EGFP–OsABCG18 fusion protein expression in tobacco leaves. M, marker; G18, total protein from tobacco leaves with transient expression of 35S::EGFP-OsABCG18; Ctrl, control, total protein from non-transgenic tobacco leaves; RbcL, Rubisco large subunit, serving as the protein loading control. The red arrow indicates EGFP–OsABCG18 protein. (B–H) Time course quantification of exported cytokinins tZ, tZR, DHZ, iP, iPR, cZR, and ABA (negative control) from tobacco leaves transformed with OsABCG18 or empty vector. The results are given as pmol g–1 WT. (I) The ratios of exported cytokinins from tobacco leaves (with EGFP–OsABCG18 and free GFP expression) in the presence or absence of 1 mM sodium vanadate at the time point of 60 min. CKs, cytokinins. (J) Quantification of exported cytokinins tZ, tZR, DHZ, iP, iPR, cZR, and ABA (negative control) from protoplasts isolated from tobacco leaves transformed with OsABCG18 or empty vector at the time point of 40 min. (K) The ratios of exported cytokinins from the tobacco protoplast (with EGFP–OsABCG18 and free GFP expression) in the presence or absence of 1 mM sodium vanadate at the time point of 40 min. Data are means ±SE (n=4). *P<0.05, ** P<0.01, and *** P<0.001 from Student’s t-test. ND, not detected.

Sodium vanadate, an inhibitor of the ABC transporter, was added to the efflux buffer, and the exported tZ, tZR, DHZ, iP, iPR, and cZR were significantly suppressed both in leaf discs and in prepared protoplasts (Fig. 5I, K), suggesting that efflux transport of cytokinins was dependent on OsABCG18. Moreover, the exported negative control ABA was not affected by the addition of sodium vanadate (Fig. 5I, K). The inhibitor experiment further supported the specific efflux transport activities of OsABCG18 for various cytokinin substrates such as tZ, tZR, DHZ, iP, iPR, and cZR.

osabcg18 displays defects in multiple agronomic traits in rice

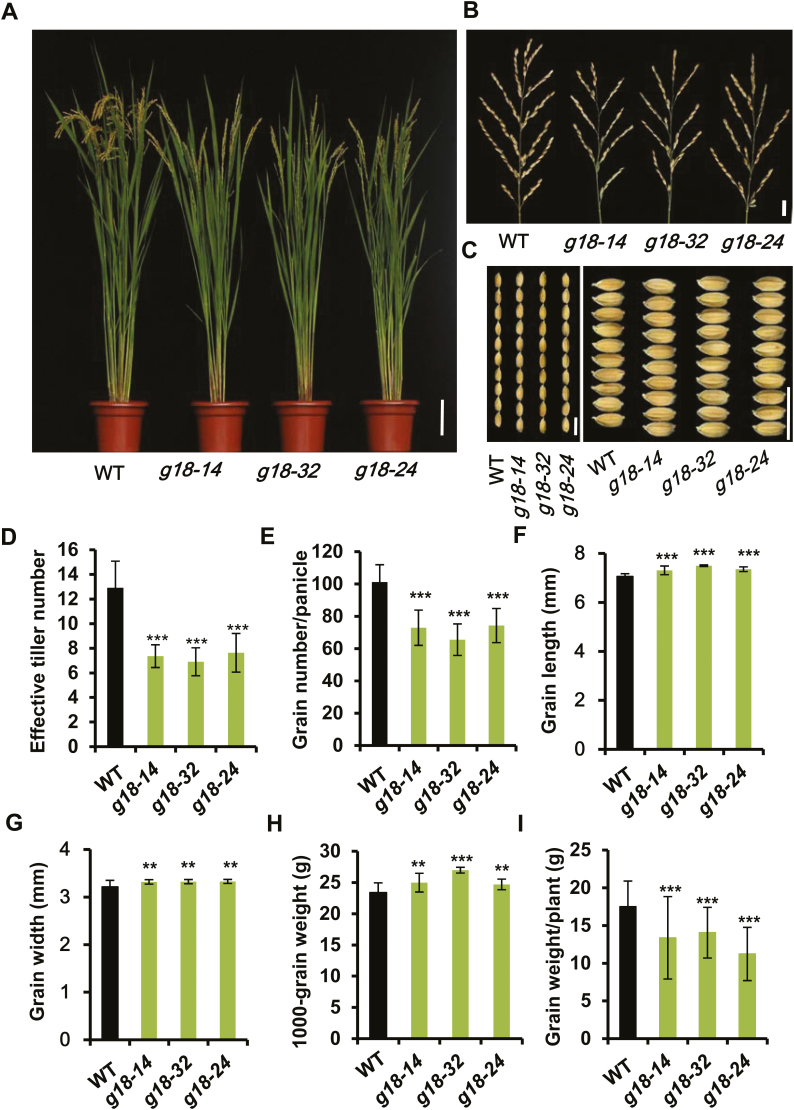

To investigate the effects of the long-distance transport of tZ-type cytokinins mediated by OsABCG18 on the agronomic traits of rice, osabcg18 and the wild type (Nipponbare) were grown in parallel in the field, and multiple agronomic traits were measured at the mature stage (Fig. 6; Supplementary Table S3). Typically, plant height was reduced from 86.5 cm in the wild type to 76.5 cm in the mutant (Fig. 6A; Supplementary Table S3). The wild type had 12.9 effective tillers, but the mutant had 7.6 effective tillers on average (Fig. 6D). Mutation of osabcg18 also repressed the transition time from the vegetative to reproductive stage, as indicated by the delay of ~4 d in heading time of the mutant compared with the wild type (Supplementary Table S3). The setting rate was reduced from ~85.6% in the wild type to 69.5% in osabcg18 (Supplementary Table S3). The panicle length was reduced from 20 cm in the wild type to 18 cm in osabcg18 (Fig. 6B; Supplementary Table S3). The number of primary branches per panicle was reduced from 9.5 to 7.6 on average (Fig. 6B; Supplementary Table S3). Thus, the grain number per panicle was reduced from 101 to 73 on average (Fig. 6E). Interestingly, the grain length and width were increased, and thus the 1000-grain weight was increased 9.3% on average (Fig. 6C, F–H). Since the grain number per plant was reduced 33%, the grain yield per plant was reduced ~26.8% on average in osabcg18 compared with the wild type (Fig. 6I). These data showed that the mutation of OsABCG18 comprehensively affected multiple important agronomic traits and significantly reduced grain yield.

Fig. 6.

Mutation of osabcg18 affected multiple agronomic traits. (A) The phenotypes of osabcg18 mutant lines g18-14, g18-32, and g18-24 at the mature stage. Scale bar=10 cm. (B) Images of the panicles in the wild type and mutant lines in (A). Scale bar=2 cm. (C) Observation of the grain length (left) and width (right) in the wild type and mutant lines in (B). Scale bar=1 cm. (D) Effective tiller number in the wild type and mutant lines in (A). (E) The grain number per panicle in the wild type and mutant lines in (A). (F) The grain length and (G) width in the wild type and mutant lines. (H) The 1000-grain weight in the wild type and mutant lines. (I) The grain weight per plant in the wild type and mutant lines. Data are means ±SD (n=15); for the measurement of grain length and width, >150 seeds were measured for each plant. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 (Student’s t-test).

Overexpression of OsABCG18 increases rice grain yield

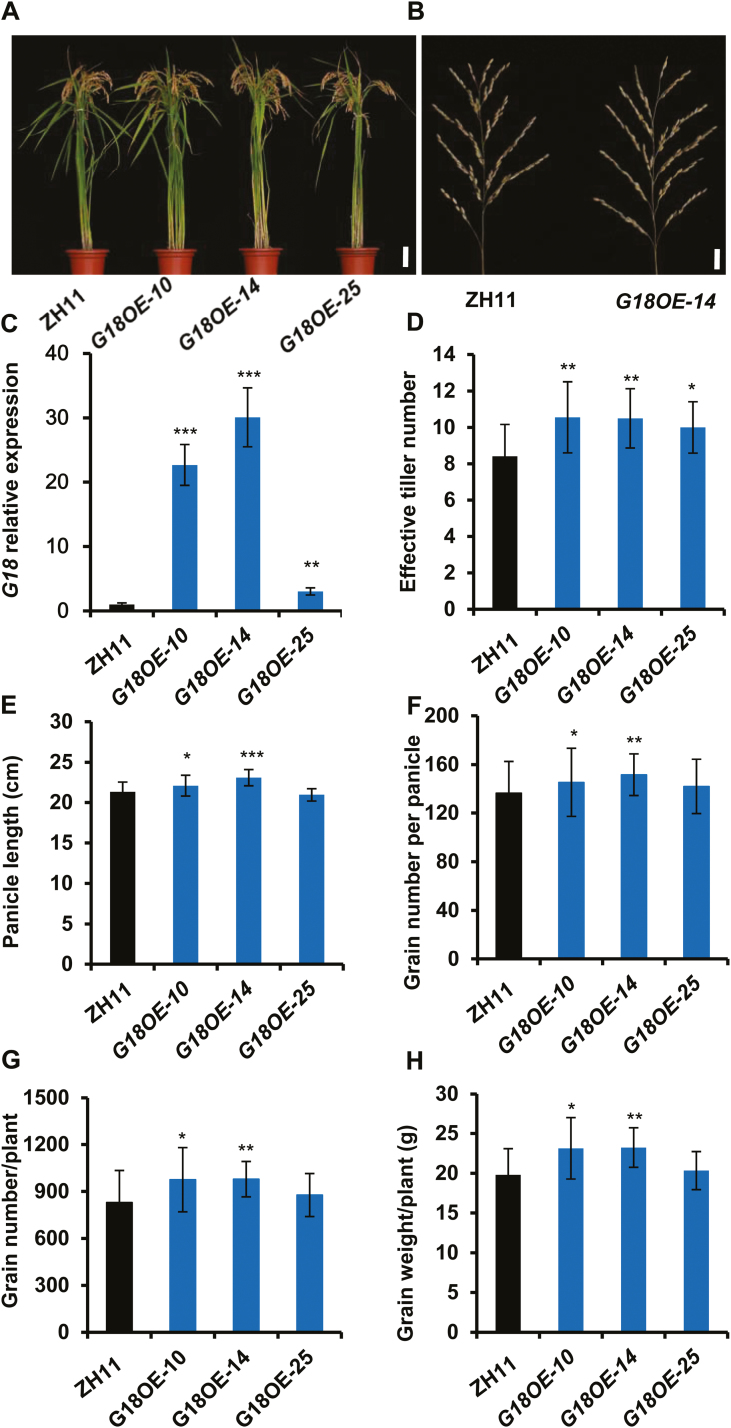

To determine the possible applications of OsABCG18 in increasing grain yield, we overexpressed OsABCG18 in wild-type rice (ZH11) using its native promoter. Expression of OsABCG18 in 13 overexpression lines at the T2 generation, as determined by qRT-PCR, demonstrated that OsABCG18 was constantly increased from 0.9 to 30 times (Supplementary Fig. S8). Two representative high expression lines (OsABCG18OE-10 and -14) and one representative low expression line (OsABCG18OE-25) were selected and transplanted to the field for assays of agronomic traits (Fig. 7A, C). Moreover, cytokinin profiling was measured in the aerial tissues of the rice seedlings of the selected overexpression lines and the wild type (Table 2). The tZ-type cytokinins (tZ+tZR) were increased by 45, 131, and 20%; DHZ values were increased by 64, 94, and 118%; iP-type cytokinins (iP+iPR) were increased by 63, 115, and 10%; and cZ-type cytokinins (cZ+cZR) were increased by 16, 18, and 5%, demonstrating that the contents of cytokinins in the shoot were significantly enhanced by the overexpression of OsABCG18 and that the amount of most cytokinins accumulated in the shoot was positively correlated with the expression levels of OsABCG18. In the root, the iP-type cytokinins (iP+iPR) were significantly increased by 62% and 85% in the two high OsABCG18 expression lines, along with the enhanced iP-type cytokinins in the shoot (Table 2), suggesting that the biosynthesis of iP-type cytokinins was increased in the OsABCG18 expression lines.

Fig. 7.

Overexpression of OsABCG18 increased the rice grain yield. (A) The phenotype of OsABCG18Pro::EGFP-OsABCG18 transgenic plant lines G18OE-10, 14, and 25 at the mature stage. Scale bar=10 cm. (B) Panicles of ZH11 and G18OE-14 lines in (A). Scale bar=2 cm. (C) Quantification of the expression of OsABCG18 in seedlings of the ZH11 and G18OE-10, -14, and -25 lines. The effective tiller number (D), panicle length (E), grain number per panicle (F), grain number per plant (G), and grain weight per plant (H) of the G18OE-10, -14, and -25 lines and the wild type in (A). Data are means ±SD (n≥12). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001 (Student’s t-test).

Table 2.

Cytokinin content (pmol g–1 FW) in roots and shoots of ZH11 and OsABCG18-OE linesa

| CKs | ZH11 shoot | G18OE-10 shoot | G18OE-14 shoot | G18OE-25 shoot | ZH11 root | G18OE-10 root | G18OE-14 root | G18OE-25 root |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tZ | 0.19±0.01 | 0.25±0.01*** | 0.29±0.06** | 0.20±0.03 | 0.04±0.01 | 0.04±0.01 | 0.04±0.01 | 0.05±0.01 |

| tZR | 0.13±0.01 | 0.21±0.01*** | 0.45±0.11*** | 0.18±0.02** | 0.14±0.02 | 0.14±0.02 | 0.16±0.03 | 0.15±0.03 |

| DHZ | 0.02± 0.01 | 0.03±0.00* | 0.03±0.01* | 0.04±0.01* | 0.05±0.02 | 0.06±0.03 | 0.06±0.04 | 0.03±0.01** |

| iP | 0.64±0.10 | 0.76±0.07* | 0.86±0.21* | 0.70±0.23 | 0.05±0.02 | 0.05±0.02 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.04±0.02 |

| iPR | 0.80±0.13 | 1.57±0.36** | 2.20±0.14*** | 0.90±0.09 | 0.40±0.02 | 0.68±0.14* | 0.78±0.22* | 0.39±0.02 |

| cZ | 1.33±0.12 | 1.60±0.20 | 1.58±0.23 | 1.32±0.29 | 0.70±0.13 | 0.59±0.17 | 0.48±0.05* | 0.68±0.06 |

| cZR | 0.73±0.16 | 0.79±0.17 | 0.85±0.13 | 0.83±0.27 | 0.86±0.11 | 0.84±0.22 | 0.79±0.09 | 1.04±0.10 |

a Roots and shoots of plants grown in water for 15 d were collected for cytokinin quantification.

Values are means ±SD (n=4); *, **, and *** indicate significant differences at P<0.05, P<0.01, and P<0.001, respectively, from Student’s t-test.

CK, cytokinin; tZ, trans-zeatin; tZR, trans-zeatin riboside; DHZ, dihydrozeatin; iP, isopentenyladenine; iPR, isopentenyladenosine; cZ, cis-zeatin; cZR, cis-zeatin riboside.

The agronomic traits of the three representative overexpression lines were investigated in the T2 generation in the field (Fig. 7; Supplementary Table S4). The effective tiller number was significantly increased by 26, 25, and 9% in the three overexpression lines G18OE-10, G18OE-14, and G18OE-25 compared with that of the wild type (Fig. 7D). The panicle length and primary number were significantly increased by 3.3% and 8.0%, respectively, in the high expression lines G18OE-10 and G18OE-14 (Fig. 7E). The grain number per panicle was increased by 6.6, 11.7, and 4.4% in G18OE-10, G18OE-14, and G18OE-25, respectively (Fig. 7F). The grain width was slightly reduced, but the grain length was significantly increased; thus, the 1000-grain weight was increased from 2.2% to 4.8% in the overexpression lines compared with the wild type (Supplementary Table S3; Supplementary Fig. S9). The grain number per plant was significantly increased by 16.1% and 16.4% in the G18OE-10 and G18OE-14 lines, respectively (Fig. 7G). Finally, the grain weight per plant was significantly increased by 17.3% and 18.3%, respectively, in the two high expression lines G18OE-10 and G18OE-14 compared with that of the wild type (Fig. 7H), indicating that the overexpression of OsABCG18 was able to improve grain yield in rice.

Discussion

Cytokinins are one of the most important plant hormones and play critical roles in plant growth and productivity (Ghanem et al., 2011; Jameson and Song, 2016). In comparison with the well-established pathways of cytokinin biosynthesis and signaling (Sakakibara, 2006; Hwang et al., 2012), understanding of cytokinin transport is limited. The characterization of OsABCG18 as a transporter essential for cytokinin transport provides new insights into the mechanism of long-distance transport of root-derived cytokinins and elucidates the essential role of cytokinin transporters in crop yield.

The characterization of OsABCG18 as a transporter responsible for cytokinin translocation suggests that OsABCG18 and AtABCG14 play a conserved role in cytokinin long-distance transport from the root to the shoot in rice and Arabidopsis. Similar to AtABCG14 (Ko et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014), OsABCG18 was found to be primarily expressed in the root stele and is located in the plasma membrane (Figs 1, 2). The expression of OsABCG18 by 35SPro or its native promoter OsABCG18Pro completely rescued the visible phenotype of the atabcg14 mutant to wild type (Supplementary Fig. S4), indicating that the biochemical functions of those two transporters were conserved between Arabidopsis and rice, model plants for dicots and monocots, respectively.

The transport activity of AtABCG14 as an exporter was investigated, but its exact substrates remain to be clearly determined (Ko et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014). Using a newly established tobacco transient expression system, we further provided new insights into the substrates of rice OsABCG18. We measured the transport activities of OsABCG18 on substrates of different internal cytokinins in tobacco to understand its transport activities (Fig. 5). The biochemical activities on tZ, tZR, and DHZ were consistent with the cytokinin profiling of the osabcg18 mutant, in which tZ, tZR, and DHZ were significantly reduced in the shoot but enhanced in the root (Table 1). However, heterologous expression of OsABCG18 in tobacco also showed that OsABCG18 exhibited transport activities for iP- and cZ-type cytokinins (Fig. 5). Consistent with this result, iP and cZ were not significantly reduced in the shoots of the osabcg18 mutant (Table 1). We speculate that there are other transporters besides OsABCG18 which can transport cZ and iP in vivo. Consistently, cZ, iP, and iPR overaccumulated in the shoot of OsABCG18 overexpression lines, further suggesting that OsABCG18 potentially exhibited transport activities for iP- and cZ-type cytokinins when it was overexpressed in vivo. Although the tobacco efflux experiments suggested that OsABCG18 had efflux transport activities for tZ, tZR, DHZ, iP, iPR, and cZR, the kinetics and transport efficiency of OsABCG18 for the different substrates remain to be clearly determined in the future. In addition, both OsABCG18 and AtABCG14 are half-size ABC transporters, which might work as homo- or heterodimers; hence, their partners in rice and Arabidopsis remain to be characterized. Moreover, determination of the transporter activity of the homo- or heterodimer in a non-plant heterologous system will more clearly address the substrates of those transporters towards different types of cytokinins.

For decades, the transport mode of cytokinins has remained obscure due to the lack of clear molecular evidence (Hwang et al., 2012). The finding that OsABCG18 is a transporter essential for cytokinin translocation, together with the physiologically well-characterized transporters AtABCG14, AtPUP14, OsPUP4, OsPUP7, and AtENT8 (Sun et al., 2005; Qi and Xiong, 2013; Ko et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014; Zurcher et al., 2016; Xiao et al., 2019), which show defects in cytokinin distribution, indicates that research on cytokinin transport mechanisms is emerging. It has been known for some time that some members of PUPs and ENTs were found to have strong influx transporter activities towards adenine, cytokinin, or cytokinin glucosides in yeast, but the physiological function remains to be understood (Duran-Medina et al., 2017; Kang et al., 2017). Recently, Arabidopsis AtPUP14 was shown to be a cytokinin importer for tZ, iP, adenine, and BA, and it was involved in maintaining extracellular cytokinin homeostasis (Zurcher et al., 2016). Detailed investigations of the known or candidate cytokinin transporters in vivo and in vitro may fully disclose the transport mechanism of cytokinin in planta.

The misdistribution of cytokinins in osabcg18 significantly affected cytokinin signaling and thus affected rice growth and agronomic traits. The overaccumulated cytokinins in the root of osabcg18 caused the short-root phenotype; this outcome is consistent with the short-root phenotype of atabcg14 and the rice CKX4 RNAi line (Gao et al., 2014), further supporting the idea that overaccumulated cytokinins in the root prohibit root growth (Riefler et al., 2006). The shoot growth of osabcg18 was delayed and plant height was decreased, and the defects were rescued by exogenous tZ but not iP, strongly suggesting that the functions of tZ-type cytokinins are critical for the shoot growth of the plants and not replaceable by iP-type cytokinins. The tiller emergence in osabcg18 was delayed and reduced, thus supporting the positive role of the root-derived cytokinin in rice tillering.

Mutation and overexpression of OsABCG18 affected multiple agronomic traits in the mature stage. The effective tillers, grain number per panicle, and crop yield were significantly reduced in osabcg18 but increased in the overexpression lines, indicating that root-derived cytokinins are essential for shoot growth and crop yield in rice. Interestingly, seed size (1000-grain weight) was increased by 9% in osabcg18 mutants and up to 4% in OsABCG18 overexpression lines compared with that of the wild type (Supplementary Tables S3, S4). These results are consistent with previous reports showing an increased seed size of the Arabidopsis CKX3 overexpression line (Werner et al., 2003), as well as in the OsCKX2 down-regulation line (Li et al., 2013; Yeh et al., 2015), suggesting that the imbalance of cytokinin homeostasis in the seed may affect grain size and weight.

Previously, the mutation of rice cytokinin oxidase 2 (OsCKX2) was shown to increase the concentration of cytokinins in the shoot and significantly increase the crop yield (Ashikari et al., 2005; Li et al., 2013; Yeh et al., 2015), providing a strategy for high-yield crop breeding. In our work, overexpression of OsABCG18 in the wild type provided a new option to increase the cytokinin concentrations in the shoots of rice. Overexpression of OsABCG18 in wild-type rice using its native promoter significantly increased tZ-, DHZ-, cZ-, and iP-type cytokinins in the shoot but did not cause visible growth defects. The increased cytokinins in the shoot enhanced the tiller number, grain number per panicle, and finally the grain yield up to 18.3% on a single-plant basis. Field trials will be performed to estimate its value in molecular breeding. The application of OsABCG18 to improve crop yield may provide a novel strategy to manipulate the distribution of cytokinins in the shoot to improve the cytokinin contents in the shoot and enhance grain yield. In addition, the osabcg18 mutant and overexpression lines of OsABCG18 may be further evaluated to determine the physiological functions of the root-synthesized cytokinins in rice.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Table S1. Primers used in this study.

Table S2. Accession codes used in this study.

Table S3. Agronomic traits of the wild type and osabcg18 at the mature stage.

Table S4. Agronomic traits of wild-type and OsABCG18 overexpression plants.

Fig. S1. Phylogenetic relationship of the half-size ABC transporter subfamily G from rice and Arabidopsis.

Fig. S2. Loss-of-function mutants of OsABCG18 generated by CRISPR/Cas9.

Fig. S3. Complementation of the growth defect of osabcg18 by tZ treatment.

Fig. S4. Expression of OsABCG18 rescued the phenotype of atabcg14.

Fig. S5. Transcriptional analysis of cytokinin-responsive genes in roots and shoots of the wild type and osabcg18.

Fig. S6. Transient expression of GFP–OsABCG18 in tobacco leaves.

Fig. S7. OsABCG18 mediated efflux transport of various cytokinins in tobacco protoplasts.

Fig. S8. Expression of OsABCG18 in OsABCG18pro::EGFP-OsABCG18 transgenic lines.

Fig. S9. Grain size of OsABCG18pro::EGFP-OsABCG18 transgenic lines.

Author contributions

KZ and JZ conceived and designed the experiments; JZ, NY, BF, YZ, EZ, MJ, and MZ performed the experiments; KZ, JZ, and YZ analyzed the data; KZ and JZ wrote and revised the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and collectively edited the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Yinong Yang (Pennsylvania State University) for providing the pRGEB31 vector, and Professor Chang-Jun Liu (Brookhaven National Laboratory) for useful discussion and sharing the materials. This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFD0100901), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31470370), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LQ17C020001), and the 1000-Talents Plan for Young Researchers of China. The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Aloni R, Langhans M, Aloni E, Dreieicher E, Ullrich CI. 2005. Root-synthesized cytokinin in Arabidopsis is distributed in the shoot by the transpiration stream. Journal of Experimental Botany 56, 1535–1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amasino R. 2005. 1955: kinetin arrives: the 50th anniversary of a new plant hormone. Plant Physiology 138, 1177–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashikari M, Sakakibara H, Lin S, Yamamoto T, Takashi T, Nishimura A, Angeles ER, Qian Q, Kitano H, Matsuoka M. 2005. Cytokinin oxidase regulates rice grain production. Science 309, 741–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batistic O, Sorek N, Schültke S, Yalovsky S, Kudla J. 2008. Dual fatty acyl modification determines the localization and plasma membrane targeting of CBL/CIPK Ca2+ signaling complexes in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 20, 1346–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishopp A, Lehesranta S, Vatén A, Help H, El-Showk S, Scheres B, Helariutta K, Mähönen AP, Sakakibara H, Helariutta Y. 2011. Phloem-transported cytokinin regulates polar auxin transport and maintains vascular pattern in the root meristem. Current Biology 21, 927–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Ma Y, Mou R, Yu S, Chen M. 2015. Analysis of 17 cytokinins in rice by solid phase extraction purification and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Chinese Journal of Chromatography 33, 715–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Huh SU, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Paek KH, Hwang I. 2010. The cytokinin-activated transcription factor ARR2 promotes plant immunity via TGA3/NPR1-dependent salicylic acid signaling in Arabidopsis. Developmental Cell 19, 284–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Lee J, Kim K, Cho M, Ryu H, An G, Hwang I. 2012. Functional identification of OsHk6 as a homotypic cytokinin receptor in rice with preferential affinity for iP. Plant & Cell Physiology 53, 1334–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chory J, Reinecke D, Sim S, Washburn T, Brenner M. 1994. A role for cytokinins in de-etiolation in Arabidopsis (det mutants have an altered response to cytokinins). Plant Physiology 104, 339–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daudu D, Allion E, Liesecke F, et al. . 2017. CHASE-containing histidine kinase receptors in apple tree: from a common receptor structure to divergent cytokinin binding properties and specific functions. Frontiers in Plant Science 8, 1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durán-Medina Y, Díaz-Ramírez D, Marsch-Martínez N. 2017. Cytokinins on the move. Frontiers in Plant Science 8, 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frébort I, Kowalska M, Hluska T, Frébortová J, Galuszka P. 2011. Evolution of cytokinin biosynthesis and degradation. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 2431–2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galuszka P, Frébort I, Sebela M, Sauer P, Jacobsen S, Pec P. 2001. Cytokinin oxidase or dehydrogenase? Mechanism of cytokinin degradation in cereals. European Journal of Biochemistry 268, 450–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan S, Amasino RM. 1995. Inhibition of leaf senescence by autoregulated production of cytokinin. Science 270, 1986–1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, Fang J, Xu F, Wang W, Sun X, Chu J, Cai B, Feng Y, Chu C. 2014. CYTOKININ OXIDASE/DEHYDROGENASE4 integrates cytokinin and auxin signaling to control rice crown root formation. Plant Physiology 165, 1035–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanem ME, Albacete A, Smigocki AC, et al. . 2011. Root-synthesized cytokinins improve shoot growth and fruit yield in salinized tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 125–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellens RP, Allan AC, Friel EN, Bolitho K, Grafton K, Templeton MD, Karunairetnam S, Gleave AP, Laing WA. 2005. Transient expression vectors for functional genomics, quantification of promoter activity and RNA silencing in plants. Plant Methods 1, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill K, Mathews DE, Kim HJ, et al. . 2013. Functional characterization of type-B response regulators in the Arabidopsis cytokinin response. Plant Physiology 162, 212–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose N, Makita N, Yamaya T, Sakakibara H. 2005. Functional characterization and expression analysis of a gene, OsENT2, encoding an equilibrative nucleoside transporter in rice suggest a function in cytokinin transport. Plant Physiology 138, 196–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose N, Takei K, Kuroha T, Kamada-Nobusada T, Hayashi H, Sakakibara H. 2008. Regulation of cytokinin biosynthesis, compartmentalization and translocation. Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang I, Sheen J, Müller B. 2012. Cytokinin signaling networks. Annual Review of Plant Biology 63, 353–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameson PE, Song J. 2016. Cytokinin: a key driver of seed yield. Journal of Experimental Botany 67, 593–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasiński M, Stukkens Y, Degand H, Purnelle B, Marchand-Brynaert J, Boutry M. 2001. A plant plasma membrane ATP binding cassette-type transporter is involved in antifungal terpenoid secretion. The Plant Cell 13, 1095–1107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson RA, Kavanagh TA, Bevan MW. 1987. GUS fusions: β-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. The EMBO Journal 6, 3901–3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakimoto T. 2001. Identification of plant cytokinin biosynthetic enzymes as dimethylallyl diphosphate:ATP/ADP isopentenyltransferases. Plant & Cell Physiology 42, 677–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Lee Y, Sakakibara H, Martinoia E. 2017. Cytokinin transporters: GO and STOP in signaling. Trends in Plant Science 22, 455–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiba T, Takei K, Kojima M, Sakakibara H. 2013. Side-chain modification of cytokinins controls shoot growth in Arabidopsis. Developmental Cell 27, 452–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko D, Kang J, Kiba T, et al. . 2014. Arabidopsis ABCG14 is essential for the root-to-shoot translocation of cytokinin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 111, 7150–7155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurakawa T, Ueda N, Maekawa M, Kobayashi K, Kojima M, Nagato Y, Sakakibara H, Kyozuka J. 2007. Direct control of shoot meristem activity by a cytokinin-activating enzyme. Nature 445, 652–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Zhao B, Yuan D, et al. . 2013. Rice zinc finger protein DST enhances grain production through controlling Gn1a/OsCKX2 expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 110, 3167–3172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CJ, Zhao Y, Zhang K. 2019. Cytokinin transporters: multisite players in cytokinin homeostasis and signal distribution. Frontiers in Plant Science 10, 693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma JF, Mitani N, Nagao S, Konishi S, Tamai K, Iwashita T, Yano M. 2004. Characterization of the silicon uptake system and molecular mapping of the silicon transporter gene in rice. Plant Physiology 136, 3284–3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda S, Funabiki A, Furukawa K, Komori N, Koike M, Tokuji Y, Takamure I, Kato K. 2012. Genome-wide analysis and expression profiling of half-size ABC protein subgroup G in rice in response to abiotic stress and phytohormone treatments. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 287, 819–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto-Kitano M, Kusumoto T, Tarkowski P, Kinoshita-Tsujimura K, Vaclavikova K, Miyawaki K, Kakimoto T. 2008. Cytokinins are central regulators of cambial activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 105, 20027–20031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane HE, Shin JJ, Bird DA, Samuels AL. 2010. Arabidopsis ABCG transporters, which are required for export of diverse cuticular lipids, dimerize in different combinations. The Plant Cell 22, 3066–3075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C, Skoog F, von Saltza M, Strong F. 1955. Kinetin, a cell division factor from deoxyribonucleic acid. Journal of the American Chemical Society 77, 1392. [Google Scholar]

- Pierman B, Toussaint F, Bertin A, Lévy D, Smargiasso N, De Pauw E, Boutry M. 2017. Activity of the purified plant ABC transporter NtPDR1 is stimulated by diterpenes and sesquiterpenes involved in constitutive and induced defenses. Journal of Biological Chemistry 292, 19491–19502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Z, Xiong L. 2013. Characterization of a purine permease family gene OsPUP7 involved in growth and development control in rice. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 55, 1119–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raines T, Blakley IC, Tsai YC, Worthen JM, Franco-Zorrilla JM, Solano R, Schaller GE, Loraine AE, Kieber JJ. 2016. Characterization of the cytokinin-responsive transcriptome in rice. BMC Plant Biology 16, 260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riefler M, Novak O, Strnad M, Schmülling T. 2006. Arabidopsis cytokinin receptor mutants reveal functions in shoot growth, leaf senescence, seed size, germination, root development, and cytokinin metabolism. The Plant Cell 18, 40–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivero RM, Kojima M, Gepstein A, Sakakibara H, Mittler R, Gepstein S, Blumwald E. 2007. Delayed leaf senescence induces extreme drought tolerance in a flowering plant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 104, 19631–19636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert HS, Friml J. 2009. Auxin and other signals on the move in plants. Nature Chemical Biology 5, 325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanov GA, Lomin SN, Schmülling T. 2006. Biochemical characteristics and ligand-binding properties of Arabidopsis cytokinin receptor AHK3 compared to CRE1/AHK4 as revealed by a direct binding assay. Journal of Experimental Botany 57, 4051–4058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanov GA, Lomin SN, Schmülling T. 2018. Cytokinin signaling: from the ER or from the PM? That is the question! New Phytologist 218, 41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara H. 2006. Cytokinins: activity, biosynthesis, and translocation. Annual Review of Plant Biology 57, 431–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Suzaki T, Soyano T, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Kawaguchi M. 2014. Shoot-derived cytokinins systemically regulate root nodulation. Nature Communications 5, 4983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmülling T. 2004. Cytokinin. In: Encyclopedia of biological chemistry. Lennarz W, Lane MD, eds. New York: Academic Press/Elsevier Science, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Šimura J, Antoniadi I, Široká J, Tarkowská D, Strnad M, Ljung K, Novák O. 2018. Plant hormonomics: multiple phytohormone profiling by targeted metabolomics. Plant Physiology 177, 476–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes IA, Runions J, Kearns A, Hawes C. 2006. Rapid, transient expression of fluorescent fusion proteins in tobacco plants and generation of stably transformed plants. Nature Protocols 1, 2019–2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Hirose N, Wang X, Wen P, Xue L, Sakakibara H, Zuo J. 2005. Arabidopsis SOI33/AtENT8 gene encodes a putative equilibrative nucleoside transporter that is involved in cytokinin transport in planta. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 47, 588–603. [Google Scholar]

- Takei K, Sakakibara H, Sugiyama T. 2001. Identification of genes encoding adenylate isopentenyltransferase, a cytokinin biosynthesis enzyme, in Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Biological Chemistry 276, 26405–26410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. 2013. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30, 2725–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai YC, Weir NR, Hill K, Zhang W, Kim HJ, Shiu SH, Schaller GE, Kieber JJ. 2012. Characterization of genes involved in cytokinin signaling and metabolism from rice. Plant Physiology 158, 1666–1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner T, Motyka V, Laucou V, Smets R, Van Onckelen H, Schmülling T. 2003. Cytokinin-deficient transgenic Arabidopsis plants show multiple developmental alterations indicating opposite functions of cytokinins in the regulation of shoot and root meristem activity. The Plant Cell 15, 2532–2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner T, Nehnevajova E, Köllmer I, Novák O, Strnad M, Krämer U, Schmülling T. 2010. Root-specific reduction of cytokinin causes enhanced root growth, drought tolerance, and leaf mineral enrichment in Arabidopsis and tobacco. The Plant Cell 22, 3905–3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Liu D, Zhang G, Gao S, Liu L, Xu F, Che R, Wang Y, Tong H, Chu C. 2019. Big Grain3, encoding a purine permease, regulates grain size via modulating cytokinin transport in rice. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 61, 581–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie K, Yang Y. 2013. RNA-guided genome editing in plants using a CRISPR–Cas system. Molecular Plant 6, 1975–1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh SY, Chen HW, Ng CY, Lin CY, Tseng TH, Li WH, Ku MS. 2015. Down-regulation of cytokinin oxidase 2 expression increases tiller number and improves rice yield. Rice 8, 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SD, Cho YH, Sheen J. 2007. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nature Protocols 2, 1565–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Forno D, Cock J, Gomez K. 1976. Laboratory manual for physiological studies of rice. Los Baños, Philippines: The International Rice Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Novak O, Wei Z, Gou M, Zhang X, Yu Y, Yang H, Cai Y, Strnad M, Liu CJ. 2014. Arabidopsis ABCG14 protein controls the acropetal translocation of root-synthesized cytokinins. Nature Communications 5, 3274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zürcher E, Liu J, di Donato M, Geisler M, Müller B. 2016. Plant development regulated by cytokinin sinks. Science 353, 1027–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.