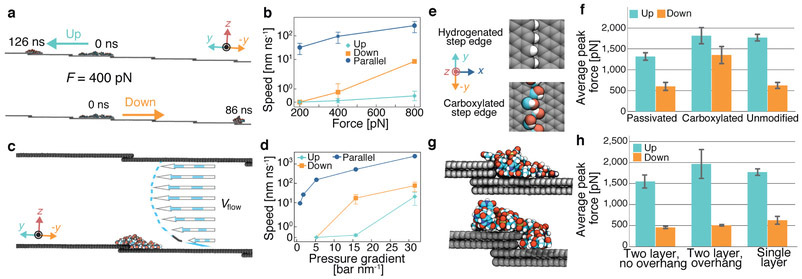

Figure 3:

Robustness of the step defect-induced asymmetry of forced displacement. (a) Constant force pulling of ssDNA across a step defect. A 20-nt ssDNA molecule is shown at the beginning and at the end of two simulations where the DNA was subject to the same magnitude constant force directed up (top) and down (bottom) the step defect (same as in Fig. 2b). Multiple periodic images of the unit cell are shown. (b) The average speed of ssDNA versus the magnitude of the constant force in the simulations where the constant force was directed up (cyan), down (orange) and parallel to (blue) the step defect. For each condition, the average velocity was computed by splitting five independent, 100 ns simulations into 5 ns fragments, beginning at the ssDNA’s first encounter with the step defect, finding the average velocity for each fragment and averaging over the fragments. (c) Schematic illustration of the simulation setup where a directional flow of water (blue-white arrows) is produced via a hydrostatic pressure difference. The water velocity profile, Vflow, is shown as dashed lines and arrows. (d) The average speed of ssDNA versus the hydrostatic pressure gradient in the simulations where the pressure gradient was directed up (cyan), down (orange) and parallel to (blue) the step defect. Note the logarithmic scale of the vertical axes in panels b and d. (e) Schematic representation of two graphene edge terminations: passivation with hydrogen (top) and carboxylation (bottom). (f) The average peak pulling force required to cross hydrogen passivated, carboxylated and pure carbon step defects in cv-SMD simulations. (g) Double layer step defects containing no (top) or a single atom (bottom) overhang. Also shown is a typical configuration of ssDNA overcoming the defects. (h) The average peak pulling force required to cross the double layer step defects in cv-SMD simulations. Supplementary Figs. 3-5 show the simulation traces summarised in this figure. Error bars represent the standard deviation from the mean.