Abstract

Fruits and vegetables are essential for healthy life. We examined the fruits and vegetables consumption by 240 caregivers and their children aged 1–17 years in peri‐urban Lima, and the ways that they were incorporated into local cuisine. A randomized cross‐sectional household survey collected information on the weight of all foods eaten the previous day (24 h) including fruits and vegetables, their preparation and serving sizes. Fruit and vegetable consumption was low and very variable: fruit intake was mean 185.2 ± 171.5 g day−1, median 138 g day−1 for caregivers and 203.6 ± 190.6 g day−1 and 159 g day−1 for children, vegetable intake was mean 116.9 ± 94.0 g day−1 median 92 g day−1 for caregivers, mean 89.3 ± 84.7 g day−1 median 60 g day−1 for children. Only 23.8% of children and 26.2% of caregivers met the recommended ≥400 g of fruit or vegetable/day. Vegetables were mainly eaten either as ingredients of the main course recipe, eaten by about 80% of caregivers and children, or as salads eaten by 47% of caregivers and 42% of children. Fruits were most commonly eaten as whole fresh fruits eaten by 68% of caregivers and 75% of children. In multivariate analysis of the extent to which different presentations contributed to daily fruit and vegetable consumption, main courses contributed most to determining vegetable intake for caregivers, and for children, main course and salads had similar contributions. For fruit intake, the amount eaten as whole fruit determined total fruit and total fruit plus vegetable intake for both caregivers and children. Local cuisine should be considered in interventions to promote fruit and vegetable consumption. © 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Keywords: food‐based dietary guidelines, dietary intake assessment, food consumption, cultural context, child public health, community‐based

Introduction

Fruits and vegetables are necessary ingredients in a healthy and balanced diet, providing health benefits beyond their contribution to satisfying dietary requirements. They play an important role in the prevention of chronic and non‐communicable diseases (NCD). Low dietary intake of fruit and vegetables is associated with increased risk of chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (Muraki et al. 2013), cardiovascular risk factors and disease (Bhupathiraju & Tucker 2011; Hartley et al. 2013; Mente et al. 2009), cancer (Wang et al. 2014; Yusof et al. 2012) and all‐cause mortality (Bellavia et al. 2013; Genkinger et al. 2004; Strandhagen et al. 2000). Meta analyses of studies on fruit and vegetables have confirmed lower mortality associated with higher consumption of these foods (Gandini et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2014). Low consumption of fruits and vegetables is now considered one of the 10 global risk factors for mortality (Lock et al. 2005), and it is estimated that inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption contributes to 2.7 million NCD deaths a year globally (Lachat et al. 2013).

Diets high in calories derived from refined carbohydrates and low in fruit and vegetables, together with reduced energy expenditure because of lack of physical exercise, are drivers of the global increase in overweight and obesity, which is related to the increase in NCDs (Kimokati & Millen 2011; Swinburn et al. 2011). Ng et al. (2014) estimated that globally, more than one third of adult men and women were overweight or obese, and that the prevalence was rising among children in developed and developing countries representing a major and increasing global health challenge, and another report put the current number of overweight and obese adults in developing countries at more than 900 million (Keats et al. 2014). This epidemic of overweight and obesity is particularly serious in middle‐income countries with few economic resources and less well‐funded health services that threaten to be overwhelmed by the sharp increases in chronic NCDs that include type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemias and associated cardiovascular disease.

Latin America, including Peru, has experienced income growth over the last few years and a rise in the prevalence of NCDs. WHO estimates that 66% of total deaths in Peru were attributable to NCDs in 2014 (World Health Organization – Noncommunicable Diseases (NCD) Country Profiles 2014), a rise from 60% in 2011 (World Health Organization‐Noncommunicable Diseases (NCD) Country Profiles 2011).

The recognition of the importance of fruit and vegetable consumption has motivated many interventions to increase fruit and vegetable intake. In some contexts, poverty and limited access to fresh fruits and vegetables may limit their consumption (Bigio et al. 2011; Rasmussen et al. 2006); however, in other contexts, households may simply prefer to consume other products, such as processed products and meat and dairy products (Delgado 2003; Reynolds et al. 2014).

In many countries, including Mexico, Argentina and Uruguay in Latin America, there have been national campaigns (e.g. ‘5‐a‐day’) to increase fruit and vegetable consumption. A review of this and other strategies to increase fruit and vegetables in the diet described some success in increasing consumption in children, particularly in school‐based interventions, (Pomerleau et al. 2005) but studies were often difficult to evaluate, results were mixed and long‐term impact could not be measured. Few trials have been reported from Latin America although published surveys measuring intake of fruit and vegetable consumption show persistently low levels (Medina‐Lezama et al. 2008). The FAO country data sheets compare dietary patterns across countries and show a remarkably consistent pattern of change: an increase in intakes of total fat, animal products, and sugar and rapid declines in the intake of cereals, fruit and some vegetables (Bermudez et al. 2003). Data from a recent national survey in Peru documented that the average number of portions of fruit or vegetable eaten per day by adults was only 2.0, ranging from 1.8 in the mountains to 2.1 in Lima, coast and jungle (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica e Informatica (INEI) 2015)

Nevertheless, successful interventions have provided hope that it is possible to increase fruit and vegetable consumption (Knai et al. 2006) even though there is some doubt about the sustainability of these interventions (Bhattarai et al. 2013). Most successful interventions are reported from the USA and Europe; few studies have been conducted in South America.

This study contributes to debates in Peru and elsewhere on the design of effective strategies for promoting fruit and vegetable consumption among urban, non‐wealthy households. We examined the role of the local culinary practice, including local preferences and recipes and the way that fruits and vegetables are included in the diet. Peru has a proud culinary heritage, which includes many characteristic dishes (recipes) that are not only found in restaurants but are common in the home. We hypothesized that successful dietary behaviour change interventions need to take into account available food options and local customs. This approach has been key in the improvement of complementary feeding practices to reduce chronic malnutrition in children (Lechtig et al. 2009; Penny et al. 2005).

This article examines fruit and vegetable consumption by caregivers and children in peri‐urban Lima, Peru, an area where fruits and vegetables are readily available year round, and reviews the way fruits and vegetables are included in the diet, thus providing a basis for designing interventions for the promoting of healthier diets that are tailored to the local context.

Key messages.

Fruit and Vegetable intake in peri‐urban Lima is lower than recommendations.

Children eat more fruit than vegetables.

Fruits and vegetables are incorporated into the diet in different ways. Fruit is often eaten as whole fruits or juices but vegetables are one constituent of recipes.

In this population the vegetable content of the main course recipe was more important than the inclusion of other vegetable presentations such as salads or soup in the determination of total vegetable intake in adults.

This difference ways fruits and vegetables are eaten should be taken into account in promotional messaging.

Subjects and methods

Design

This paper describes the results of a randomized cross‐sectional household survey of 24‐h recall consumption data for the principal caregiver and one child of the household including all meals, their ingredients as well as the recipes and presentations and the serving sizes. This analysis is part of a broader scoped study to look at determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption with emphasis on the food value chain and intra‐household factors.

Population

The study was conducted during January–March of 2014 in one district in a peri‐urban area of Lima.

Subjects

Family/caregiver inclusion criteria were the following: (i) have a child between 1 and 17 years; (ii) be the person in charge of the food purchases; (iii) be eating ‘normally’, i.e., with no illness leading to temporary dietary modification; and (iv) consent to participate. Exclusion criteria included the following: (i) owning of a shop, market stall or restaurant where fruits/vegetables/juices or preparations of these are sold; (ii) caregiver or child with an illness condition and/or a recent dietary change; and (iii) children who were independent and not at school.

The study area was divided into 50 geographical units. Each unit was comprised of approximately eight housing blocks, and each block contained around 20 houses. Based on previous experience, we estimated that each block provided approximately 20 households with children within the age group, only one to be included, and that 50% would provide consent. Thus, the eligible population was estimated at 2000, the expected percent of individuals satisfying the requirement of 400 g fruit and vegetable was 20%, and with power of 20 and 95% confidence interval, the calculated sample size was 220 (http://www.openepi.com/SampleSize/SSPropor.htm), increased to 240 to allow for some error in the estimates.

We used a two stage enrollment with a first visit to explain the study, make an appointment for the dietary study and conduct a socio‐economic survey. At the second visit, 1–2 weeks later, all geographic units were visited, the households visited in order and the diet assessment was conducted if the caregiver and child were present and both gave renewed consent/assent. If it was not possible to do the study that day, the next previously selected household was visited. Sixty households were not included in this second phase: 18 (6%) because the caregiver was absent, 22 (7.3%) because it was no longer convenient, 4 (1.3%) for illness and 13 (4.3%) because the sample size was complete.

Ethics

The study was approved by the independent institutional ethics review committee. Parents of children and adult respondents gave verbal consent to participate, and children over 8 years also gave their assent.

Data collection instruments

The first visit was conducted by experienced field workers who collected socio‐economic information and conducted a food frequency questionnaire. In parallel, an anthropologist and nutritionist collected qualitative information on fruit and vegetable availability, food budgets, expenditure on food and factors that determined fruit and vegetable purchases. At the second visit, a 24‐h recall of food that included direct weighing was conducted by three experienced local nutritionists. In this analysis, we present results of this reconstruction of the previous days diet. Caregivers were asked to describe all meals, snacks and drinks consumed during the previous day or night, the time the food was eaten and the size of individual items such as fruit and the serving size of each cooked meal. The interview took place in the home so that sizes of plates, cups, serving spoons and other utensils could be assessed and compared with the models and size standards used by the study. The nutritionists probed for foods or ingredients that might be forgotten and asked about the day's activities to ensure that nothing was excluded. We reconstructed the weights of each ingredient included in recipes and the final preparation by measuring jugs, cups and serving spoons and weighing the saucepan used with and without the same amount of food. We observed the plate used and questioned the caregiver on the amount served to the child and the caregiver, almost always the mother, and the amount actually eaten. The amount of any food items eaten outside the home was estimated. Children aged 8 years or older participated in their dietary recall.

Data entry and analysis

Individual foods were coded using the Institution's food database, which includes >2000 items and all raw and cooked foods commonly available in Lima. Prepared fruit and vegetable weights were converted to the raw food equivalent weight. In the case of fruit drinks, only the fruit and not the water was considered in the amount consumed. Drinks made with artificial fruit flavouring or from fruit peel alone were not included.

All fruit and vegetable ingredients were included in the analysis except garlic, which is presented in small amounts (1–5 g) in many recipes and this, and ground chilli, was not considered to be nutritionally significant. A serving was defined as the portion or ration of a specific food item or recipe preparation that was served and consumed at one time, for instance a whole fruit, or a given recipe for instance a serving of a stew. A given recipe might be eaten several times in the day, for instance at lunch and supper, and in this case, this was considered as two servings. Two or more preparations served at the same time on the same plate were considered as one serving. We use serving to refer to the amount of a preparation of individual food item presented to the child. If the child had a second helping at the same time, or if they ate a second fruit within 15 min, then the servings were considered as one serving, but if the same preparation was served again later in the day, for instance for supper, a common occurrence, this was regarded as a new serving.

Because the purpose of the analysis was to explore fruit and vegetable consumption in the context of local cuisine, we coded the way food was presented at meals in two levels: by presentations of a meal, for example ‘main courses’ – the principal dish served at lunch or evening meal; ‘salads’ a side salad (raw or cooked vegetables), or a ‘pudding containing fruit’. In addition, within ‘main courses’, we distinguished recognizable recipes on the basis of vegetable content and cooking method so that, for instance, ‘a meat stew with vegetable’, ‘fried mixture of vegetables’ and if possible recipes with specific local names such as ‘locro’ – squash stew were individually labelled. This more detailed categorization allowed us to identify those recipes that were particularly high in vegetable content.

Before data entry, forms were revised by another nutritionist. The data were entered in programmes developed for the study and included quality control checks. Food item codes and preparations were cross‐checked for consistency in the coding of preparations, and outlying values were double checked. For the construction of ‘servings’, the data was downloaded to excel files and all food items served and eaten during the day were examined and divided into servings using the predefined rules. If the same preparation was eaten twice in the day, each ingredient was halved for each serving. If certain ingredients were eaten at one meal but not another was taken into account.

The study date base was constructed in spss version 20 (IBM SPSS, New York) files and all descriptive statistics: mean +/− standard deviation, median and interquartile ranges were calculated for the daily amount of fruit and vegetables eaten by the caregiver and child and for each serving. Multivariable statistical models that included the amounts of the different presentations, transformed to the square root in order to normalize, were also analyzed to quantify their relative importance as determinants of the 24‐h consumption of fruit and vegetables. These analyses also included as co‐variables: child and mother's age, maternal education and place of birth.

Results

Fruit and vegetable consumption

Table 1 shows the total daily consumption of fruit and vegetables on the day prior to the interview by the children and principal caregiver; all but five caregivers were the child's mother. Consumption was low by both the caregivers and children, only 23.8% of children and 26.2% of caregivers ate the recommended daily amount of ≥400 g of fruit and vegetables (World Health Organization 2004) However, no children or caregivers reported eating no fruit or vegetable. Only a few children (6.7%) and caregivers (2.9%) ate no vegetable, whereas 6.7% of children and 9.6% of mothers ate no fruit in keeping with the higher fruit consumption in children median 159 g day−1 compared with 138 g day−1 for caregivers (Table 1). On average, children ate less vegetable, median 60 g day−1 compared with the caregivers, 92 g day−1, but the amount of vegetable eaten by children increased with age and children aged >12 years on average ate slightly more than the adults (median 109 g versus 92 g). The amount of fruit eaten by children was greatest amongst school‐aged children (5–12 years) but decreased in the adolescents (Table 1). There was only a weak although statistically significant association between the child and mothers fruit consumption, Pearson correlation 0.341 p < 0.01 and child and mothers vegetable consumption, Pearson correlation 0.369, p < 0.01. On average, both caregivers and children ate considerably more fruit than vegetable (Table 1). There was considerable variability in the consumption of both fruit and vegetable for both caregivers and children (Table 1).

Table 1.

Fruit and vegetable consumption by caregivers and children

| Fruit (g/24 h) | Vegetables (g/24 h) | Fruit and vegetables (g/24 h) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Eating fruit (N) | Mean ± SD | Median | Interquartile range | Eating vegetable (N) | Mean ± SD | Median | Interquartile range | Eating F&V (N) | Mean ± SD | Median | Interquartile range | |

| Caregivers | 240 | 217 | 185.2 ± 171.5 | 138 | 218.5 | 233 | 116.9 ± 94.0 | 92 | 116.0 | 240 | 302.0 ± 197.4 | 271 | 255.5 |

| All children (1–17 years) | 240 | 224 | 203.6 ± 190.6 | 159 | 230.0 | 224 | 89.3 ± 84.7 | 60 | 105.5 | 240 | 292.9 ± 224.2 | 249 | 248.0 |

| Children by age group | |||||||||||||

| <5 years | 67 | 63 | 161.5 ± 128.8 | 127 | 176.0 | 62 | 62.0 ± 69.5 | 39 | 68.0 | 67 | 223.5 ± 148.4 | 180 | 207.0 |

| 5–12 years | 109 | 102 | 218.0 ± 167.1 | 202 | 221.0 | 102 | 88.1 ± 78.6 | 67 | 94.0 | 108 | 306.1 ± 196.1 | 281 | 271.0 |

| >12 years | 64 | 59 | 213.7 ± 265.1 | 127 | 251.0 | 60 | 130.9 ± 109.4 | 109 | 156.0 | 62 | 344.6 ± 301.2 | 285 | 281.5 |

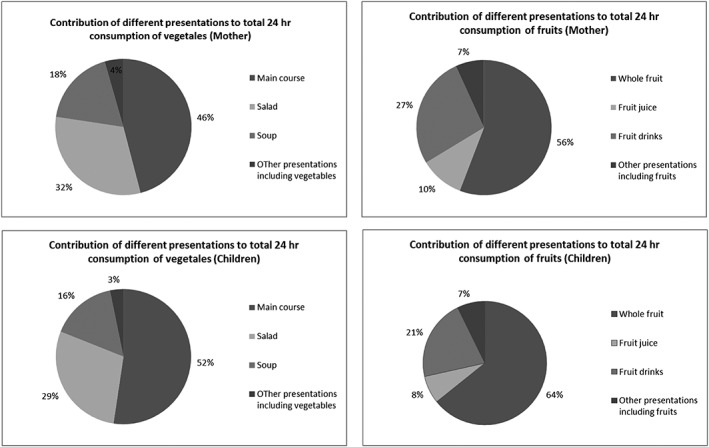

Fig. 1 shows how fruit and vegetables were included in the diet of children and how this contributes in terms of the percent of fruit or vegetable eaten in 24 h.

Figure 1.

Contribution of different food presentations to 24 hr consumption of fruit and vegetables in mothers and children.

Fruit consumption according to preparation

Fruits were most commonly eaten as whole, fresh fruits, and these contributed the largest amount of fruit in the diet of both caregivers and children (Table 2). Children often ate fruit more than once in the previous day, 30% ate whole fruit twice and 9% three times. Fruit salads were only eaten by six children (2.5%), but the median serving size was 187 g.

Table 2.

Fruit consumption in selected presentations

| Food presentation containing fruit | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole, fresh fruit | Fruit juice | Fruit drink | |

| Caregivers' consumption | |||

| Number of caregivers (%) | 162 (67.5) | 36 (15.0) | 148 (61.7) |

| Fruit Consumption/person eating the food or drink/day (g) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 176.0 ± 127.6 | 208.8 ± 110.5 | 37.84 ± 44.9 |

| Median | 144.5 | 215 | 20 |

| Interquartile range | 160.0 | 136.5 | 46.5 |

| Number of servings of food or drink | 237 | 38 | 230 |

| Serving size (g) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 116.0 ± 71.7 | 186 ± 96.3 | 24.0–29.1 |

| Median | 100 | 188 | 12 |

| Interquartile range | 71.0 | 135.3 | 31.0 |

| Children's consumption | |||

| Number of children (%) | 178 (75.1) | 31 (13.1) | 142 (59.9) |

| Fruit consumption/person eating the food or drink/day (g) | |||

| Mean ± SD (g) | 205.9 ± 172.1 | 143.7 ± 86.0 | 30.8 ± 39.8 |

| Median (g) | 163 | 125 | 15.5 |

| Interquartile range | 180.0 | 152.0 | 31.0 |

| Number of servings of food or drink | 260 | 32 | 190 |

| Serving size (g) | |||

| Mean ± SD (g) | 137.6 ± 130.7 | 145 ± 77.5 | 22.9 ± 30.6 |

| Median (g) | 110 | 127 | 14 |

| Interquartile range (g) | 104.3 | 152.3 | 20.9 |

The second most important source of fruit was in pure fruit juices, but only 36 caregivers and 31 children consumed these (Table 2). Fruit drinks, that is, a mixture of fruit and water, were consumed by more children and adults, but the fruit content of these servings was small, median 12–14 g per drink (Table 2). Fruit was also eaten in fruit puddings such as rice with fruit (not shown in the table); 32 adults ate 38 servings, but the amount of fruit content was small: the median serving size was 27.5 g. Yogurt or milk recipes containing fruit (not shown in table) were eaten by seven caregivers and provided a median 128 g per person per day for those women, although the median serving size was 64 g.

Vegetable consumption according to preparation

Caregivers ate more vegetables than children (Table 3). Vegetable intake by children increased with age (Table 1). There was wide variation in the amounts of vegetables consumed at all ages, with an asymmetrical distribution because many adults and children ate very small amounts of vegetables mostly the onions and tomato used in many main course recipes. In contrast with the fruit consumption, with the exception of salads, vegetables were mainly eaten as part of recipes that included other foods and where the vegetable content was often low (Table 3). For instance, 81.3% of mothers ate main dishes containing vegetable, usually twice a day, and sometimes also at breakfast, but the median amount of vegetable in a main course serving of a recipe was only 28 g for adults and 16 g for children, and for some individuals (Table 3), this was the only vegetable intake. Only 40 (16.7%) of children ate servings with >80 g vegetable (considered as one ration). However, there was considerable variation in the vegetable content of recipes included as main courses, for instance, the amount of vegetable eaten in main courses servings varied from 0.5–194 g/serving for adults and 1–284 g/serving for children.

Table 3.

Vegetable consumption from selected presentations

| Food presentation containing Vegetable | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main course | Salad | Soup | |

| Caregivers' consumption | |||

| Number of caregivers (%) | 195 (81.3) | 113 (47.1) | 83 (34.6) |

| Vegetable consumption/person/day eating the recipe (g) | |||

| Mean ± SD (g) | 60.2 ± 61.2 | 86.6 ± 66.1 | 61.9 ± 43.1 |

| Median | 38 | 70 | 55 |

| Interquartile range | 74.0 | 84.0 | 51.0 |

| Number of caregivers eating ≥80 g | 54 | 51 | 21 |

| Number of caregivers eating ≥160 g | 25 | 19 | 3 |

| Number of servings of presentation | 259 | 132 | 105 |

| Size of servings (g)* | |||

| Mean | 29.1 ± 34.7 | 73.9 ± 52.8 | 47.7 ± 30.0 |

| Median | 28 | 64.0 | 45.0 |

| Interquartile range | 46.8 | 73.0 | 40.6 |

| Children's consumption | |||

| Number of children (%) | 185 (78.1) | 100 (42.2) | 62 (26.2) |

| Vegetable consumption/person/day eating the recipe (g) | |||

| Mean ± SD (g) | 49.1 ± 59.8 | 77.5 ± 79.4 | 60.5 ± 53.6 |

| Median | 26.0 | 51.5 | 41.5 |

| Interquartile range | 52.0 | 64.5 | 54.0 |

| Number of children eating ≥80 g | 40 | 32 | 15 |

| Number of children eating ≥160 g | 14 | 11 | 5 |

| Number of servings of presentation | 328 | 118 | 78 |

| Size of servings (g)* | |||

| Mean | 30.7 ± 38.1 | 66.1 ± 70.3 | 47.1 ± 43.1 |

| Median | 16 | 43 | 35 |

| Interquartile range | 31.6 | 56.8 | 52.8 |

In this table, when two or more recipes were served together, they have been added together.

Certain relatively high content recipes of vegetable ‘main courses’ could be identified based on their ingredients as typical Peruvian recipes, for instance, typical stews made with a mixture of vegetables usually including onion, carrot and tomato; sautéed vegetables such as broccoli or French beans, and ‘locro’ a dish made with squash.

Salads were the food presentation that provided most vegetable per serving with a median consumption of 43 g of vegetable/serving/child, and 32 (13.3%) of children ate ≥80 g of vegetable as a salad, but salads were almost always only eaten once a day (Table 3). Soups contained only small amounts of vegetable nevertheless, although unusual, 11 mothers consumed >80 g of vegetable in single servings of soup. A small number of children ate separately served vegetables, for instance, fresh corn on the cob. There were seven servings of this and four provided >80 g of vegetable.

Adjusted multivariable models were constructed to study the relative role of different preparations in determining the composition of the 24 dietary intake of fruit and vegetables: In these models (Table 4), we demonstrate the extent to which different preparations or recipes (for instance, main course, salads or soups for vegetables and whole fruit, juice and fruit drinks for fruit) contribute differently to the daily consumption of fruit and vegetable. The adjusted r 2 for fruit consumption in children was 0.950 with a highest standardized coefficient (beta) for whole fruit of 0.888 (p < 0.01). In the analysis of vegetable consumption, the r 2was 0.896, the amount of main course had the highest standardized coefficient at 0.667 (p < 0.01) but the standardized coefficient for salad was 0.657 (p < 0.01). Age was also significant (p = <0.01) but with a low standardized coefficient of 0.057. Results were similar for mothers with r 2 24‐h fruit consumption 0.91 with standardized coefficient for whole fruit of 0.800 (p < 0.01). Results for 24‐h vegetable consumption was r 2 0.81 with a standardized coefficient beta of 0.732 (p < 0.01) for main course followed by 0.677(p < 0.01) for salads and 0.488 (p < 0.01) for soups. Thus, the contribution of vegetables in the main course contributed most to determining total vegetable intake. In other words, the vegetable content of the main course recipe was more important than the inclusion of other vegetable presentations such as salads or soup in the determination of total vegetable intake in adults.

Table 4.

Multivariable statistical model of the relative role of different presentations in the determination of total 24‐h dietary intake of fruit and vegetables

| Unadjusted coefficients | Standard error | Standardized coefficients | P‐value | Adjusted R 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | ß | ||||

| Caregivers | |||||

| Constant | 4.829 | 0.906 | |||

| Whole fruit | 0.522 | 0.017 | 0.639 | <0.01 | |

| Fruit juice | 0.426 | 0.022 | 0.391 | <0.01 | |

| Main course | 0.449 | 0.028 | 0.337 | <0.01 | |

| Salad | 0.366 | 0.024 | 0.318 | <0.01 | |

| Soup | 0.311 | 0.030 | 0.212 | <0.01 | |

| Fruit drink | 0.303 | 0.032 | 0.191 | <0.01 | |

| Other puddings with fruit | 0.291 | 0.035 | 0.166 | <0.01 | |

| Other vegetable preparations | 0.390 | 0.049 | 0.161 | <0.01 | |

| Children | |||||

| Constant | 3.309 | 0.91 | |||

| Whole fruit | 0.595 | 0.017 | 0.691 | <0.01 | |

| Salad | 0.406 | 0.029 | 0.294 | <0.01 | |

| Main course | 0.440 | 0.032 | 0.278 | <0.01 | |

| Fruit juice | 0.409 | 0.030 | 0.261 | <0.01 | |

| Soup | 0.294 | 0.036 | 0.162 | <0.01 | |

| Fruit drink | 0.343 | 0.039 | 0.173 | <0.01 | |

| Other puddings with fruit | 0.302 | 0.040 | 0.150 | <0.01 | |

| Other vegetable preparations | 0.450 | 0.063 | 0.139 | <0.01 | |

| Child's age (years) | 0.071 | 0.027 | 0.054 | <0.01 | |

Includes age of caregivers and child, place of birth and education level of the mother.

In Table 4, we show the relative role of the different preparations in the determination of the 24‐h combined fruit and vegetable intake when both fruit and vegetable preparations were included in the fully adjusted model. In these models, the amount of whole fruit eaten had the highest coefficient, but for caregivers, the amount of fruit juice was the second, and vegetable eaten in the main course the third, most important contributing preparation while for children the second most important was salads.

Discussion

This study explores the dietary patterns, in particular, the amounts and forms in which fruit and vegetables are consumed in a peri‐urban population of Lima, Peru, information that will benefit the design of potentially effective educational interventions. Fruit and vegetable consumption in our sample fell well short of the recommended intake of 400 g day−1 for both mothers and children. Fruit intake was higher in children than adults. Vegetable consumption was low and particularly low in children. This is in keeping with findings from a previous study in another city of Peru (PREVENCION), but in this study, we have described more detail about the way that fruits and vegetables were incorporated in the diet.

Fruits and vegetables were included in the diet in different ways. Whole fruits were the main form that fruits were consumed, and this was higher in children than mothers. Children also ate more fruit, and it was only slightly dependent of mothers' intake. Those children who had higher total fruit and vegetable intake ate more fruit. Whole fruits were responsible for most fruit intake. Fruit salads while not common, were particularly good sources of fruit with the added advantage of providing variety.

These results suggest that targeting fruit consumption especially in children should be further investigated as a possible successful strategy for interventions. This is in keeping with the literature that suggests that interventions in general have been more successful in increasing fruit rather than vegetable intake (Evans et al. 2012). Our study was conducted in Lima where there is a wide variety of affordable fruit available, and in this context, the promotion of fruits as whole fruit or fruit salads would potentially increase intakes, but further studies are needed to identify and address the barriers and facilitators for this strategy.

Few studies have looked at the independent effect of fruit versus vegetables on long‐term outcomes but, and as stated by Liu et al., variety is also an essential part of the target for fruit and vegetable consumption. Current understanding of the mechanisms whereby fruits and vegetable confer benefit suggests that synergies between fruits, vegetables and whole grains are necessary to maximize optimal benefit (Lui 2013).

Vegetables were incorporated into the diet in a very different way to fruit in this population. Almost all cooked Peruvian savoury dishes, referred to here as recipes, include ‘aderezo’ (i.e. the frying of garlic and or onions and sometimes tomato to add flavour and as a base for the preparation). However, we found that there was a very large variation in the vegetable content of main courses and only certain recipes contained relatively large amount of vegetables. When these dishes were included in the daily food, they were highly predictive of vegetable consumption especially for the mothers' diets. These main courses with higher vegetable content were often recognizable as typical Peruvian recipes suggesting that the promotion of these recipes would be a way of increasing vegetable intake.

Salads were also important sources of vegetable. However, this study was performed in summer, a time when salads are traditionally eaten, and they may play a smaller part in vegetable consumption in the winter. Soups are a more usual accompaniment to main meals in winter but contain only small amounts of vegetable and contributed less to determining vegetable intake in this study.

Dietary interventions to increase fruit and vegetable intake can be successful (Ammerman et al. 2002; Pomerleau et al. 2005) particularly in high‐risk groups. A review of studies that focused on children reported an increase of between 0.3 and 0.99 servings/day and a Cochrane review of dietary advice in adults interventions to reduce cardiovascular risk in adults reported an almost doubling in fruit and vegetable servings per day – 1.88 (95% CI 1.07,2.7) (Rees et al. 2013). Another recent metanalysis (Bhattarai et al. 2013) of interventions in primary health care settings in the USA, UK, Japan and Italy reported small beneficial changes in consumption of fruit and vegetables of 0.5 servings/day. Campaigns to promote ‘5‐a‐day’ five portions of fruit or vegetable/day have been implemented in Latin America, but we are not aware of any published trials of their impact on fruit and vegetable consumption in Peru.

This common approach to dietary advice is based on estimations that five portions of fruit or vegetable are desirable based on the 1990 WHO dietary guidelines that suggested a target of 400 g/person/day as being a reasonable and healthy amount of fruit and vegetable. In order to translate this total amount into a more readily understood message for the public, a standard portion size or serving of 80 g, roughly equivalent to an average size of a single apple or mandarin orange, was used to define a recommendation of five servings of fruit or vegetables every day (BMJ). These recommendations are now included in many national dietary guidelines, for instance, the USA recommends 4–5 portions of fruit or vegetables for a diet of 2000 kcal per day.

Our study suggests that a complementary strategy to increase intake, in particular of vegetables, would be to promote those traditional recipes that naturally contain high amounts of vegetable. This approach is novel in that rather than specific food items or dietary patterns, we have sought to analyze the ways in which fruits and vegetables are eaten, how they are included in the local cuisine and to identify specific preparations or dishes that are major sources of vegetable in the diet, that can be promoted to increase overall fruit and vegetable content. In this way, dietary advice does not need to promote a diet that may not be typical of local cuisine but selects from that cuisine preparations or dishes to be encouraged. Detailing the amounts of fruit and vegetable in different preparations and the amounts actually consumed by both children and adults in the household can give us the tools to develop the messages and to complement existing dietary advice for successful behaviour change interventions.

Our study has some weaknesses. We only collected information from one area of a district of Lima and on a single day. Amounts were estimated, albeit using methodology of direct weighing of kitchen equipment when possible combined with on careful questioning about each serving size and the amount actually eaten by the index child and the caregiver. We collected data on caregiver (usually the mother)/child pairs, and further analysis would be useful to understand to what extent maternal dietary patterns influence the child's consumption.

The study was performed in summer when children were not at school, which likely changes dietary habits. In summer, fruits and vegetables are cheaper and salads may be eaten in preference to hot plates such as soups, which may mean that yearly average intakes may be lower than our estimates.

Our study adds data to support the need for public health measures to increase consumption. A particular strength of this study is that it not only provides estimates of amounts of fruit and vegetable consumption but also describes how these foods are included in the diet and to what extent the choice of preparations determines daily intakes. Although estimates of fruit and vegetable intake based on the reported number of rations or portions of fruits and vegetables are conducted as part of the health and demographic surveys including in Peru (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica e Informatica (INEI) 2015), detailed quantitative data are much less common especially in these high‐risk urban populations of middle‐income countries experiencing this health transition.

From the culinary point of view, fruits and vegetables are not interchangeable, and the way that they are present in preparations and meals may be quite distinct between different countries and populations. Interventions to promote increased consumption of fruits and vegetables need to take this into account.

In conclusion, this study highlights the deficiencies of current diets in this population and adds to the evidence that interventions and programmes are needed to motivate an increase in the amount of fruits and vegetables in the diet and provides evidence to support the use of strategies that focus on promoting specific easily identified local dishes as a complement to programmes that seek to raise awareness of the benefits of fruit and vegetable consumption.

Source of funding

Funding for this research was provided by the CGIAR Global Research Program Agriculture for Nutrition and Health.

Conflict of interest

Mary Penny, Krysty Meza, Hilary Creed‐Kanashiro and Margot Marin have all participated in research projects funded by Nestle Ltd. Mary Penny has conducted consultancies for Food manufacturers: Alicorp S.A.C. and Backus. Jason Donovan declares no conflict of interest.

Contributions

MP, JD, HC‐K designed the research. KM assisted with research design and supervised fieldwork. MP and MM undertook the analysis of the data. MP wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and contributed to later drafts and the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the field staff of the IIN in Lima, Nutritionist Lizette Ganoza for maintenance of the IIN's list of food codes, and to the parents and children who participated in the study.

Penny, M. E. , Meza, K. S. , Creed‐Kanashiro, H. M. , Marin, R. M. , and Donovan, J. (2017) Fruits and vegetables are incorporated into home cuisine in different ways that are relevant to promoting increased consumption. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13: e12356. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12356.

References

- Ammerman A.S., Lindquist C.H., Lohr K.N. & Hersey J. (2002) The efficacy of behavioral interventions to modify dietary fat and fruit and vegetable intake: a review of the evidence. Preventive Medicine 35, 25–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellavia A., Larsson S.C., Bottai M., Wolk A. & Orsini N. (2013) Fruit and vegetable consumption and all cause mortality: a dose response analysis. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 98, 454–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez O., Tucker K. & Mayer J. (2003) Trends in dietary patterns of Latin American populations. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 19 (1), S87–S99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai N., Prevost A.T., Wright A.J., Charlton J., Rudisill C. & Gulliford M.C. (2013) Effectiveness of interventions to promote healthy diet in primary care: systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC Public Health 13, 1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigio R.S., Verly Junior E.I., de CastroI M.A., Galvão César C.L., Fisberg R.M. & Lobo Marchioni D.M. (2011) Determinants of fruit and vegetable intake in adolescents using quantile regression. Revista Saúde Pública 45 (3), 448–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhupathiraju S.N. & Tucker K.L. (2011) Coronary heart disease prevention: nutrients, foods, and dietary patterns. Clinica Chimica Acta 412, 1493–1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado C. (2003) Rising consumption of meat and milk in developing countries has created a new food revolution. Journal of Nutrition 133 (11 Suppl 2), 3907S–3910S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans C.E.L., Christian M.S., Cleghorn C.L., Greenwood D.C. & Cade J.E. (2012) Systematic review and meta‐analysis of school‐based interventions to improve daily fruit and vegetable intake in children aged 5 to 12y. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 96, 889–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandini S., Merzeninch H., Robertson C. & Boyle P. (2000) Meta‐analysis of studies on breast cancer risk and diet: the role of fruit and vegetable consumption and the intake of associated micronutrients. European Journal of Cancer 36, 636–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genkinger J.M., Platz E.A., Hoffman S.C., Comstock G.W. & Helzlsouer K.J. (2004) Fruit, vegetable, and antioxidant intake and all‐cause, cancer, and cardiovascular disease mortality in a community‐dwelling population in Washington County, Maryland. American Journal of Epidemiology 160, 1223–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley L., Igbinedion E., Holmes J., Flowers N., Thorogood M., Clarke A. et al. (2013) Increased consumption of fruit and vegetables for the primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013 (6), CD009874 DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009874.pub2 Instituto Nacional de Estadistica e Informatica ‐ NEI NCDs ref to F and V consumption. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadistica e Informatica (INEI) . (2015) Peru:Enfermedades No transmisibles y transmisibles, 2014. Available from INEI at ventas@inei.gob.pe.

- Keats S., Wiggins S., Overseas Development Institute (2014) Future diets, implications for agriculture and food prices. Available at: http://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/8776.pdf (Accessed 8 September 2015)

- Kimokati R.W. & Millen B.E. (2011) Diet, the global obesity epidemic, and prevention. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 111, 1137–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knai C., Pomerleau J., Lock K. & McKee M. (2006) Getting children to eat more fruit and vegetables: a systematic review. Preventive Medicine 42, 85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachat C., Otchere S., Roberfroid D., Abdulai A., Seret F.M.A. et al. (2013) Diet and physical activity for the prevention of noncommunicable diseases in low‐ and middle‐income countries: a systematic policy review. PLoS Medicine 10 (6), e1001465 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechtig A., Cornale G., Ugaz M.E. & Arias L. (2009) Decreasing stunting, anemia, and vitamin A deficiency in Peru: results of the Good Start in Life Program. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 30, 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock K., Pomerleau J., Causer L., Altmann D.R. & McKee M. (2005) The global burden of disease attributable to low consumption of fruit and vegetables: implications for the global strategy on diet. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 83, 100–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui R.H. (2013) Health‐promoting components of fruits and vegetables in the diet. Advances in Nutrition 4, 384S–392S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina‐Lezama J., Morey‐Vargas O.L., Zea‐Díaz H., Bolaños‐Salazar J.F., Corrales‐Medina F., Cuba‐Bustinza C. et al. (2008) Prevalence of lifestyle‐related cardiovascular risk factors in Peru: the PREVENCION study. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 24, 169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mente A., de Koning L., Shannon H.S. & Anand S.S. (2009) A systematic review of the evidence supporting a causal link between dietary factors and coronary heart disease. Archives of Internal Medicine 169, 659–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraki I., Imamura F., Manson J.E., Hu F.B., Willett W.C., van Dam R.M. et al. (2013) Fruit consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from three prospective longitudinal cohort studies. British Medical Journal 347, f5001 DOI: 10.1136/bmj.f5001 Errata: BMJ 2013;347:f6935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M., Fleming T., Robinson M., Thomson B., Graetz N., Margono C. et al. (2014) Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 384, 766–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penny M.E., Creed‐Kanashiro H.M., Robert R.C., Narro M.R., Caulfield L.E. & Black R.E. (2005) Effectiveness of an educational intervention delivered through the health services to improve nutrition in young children: a cluster‐randomised controlled trial. Lancet 365, 1863–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau J., Lock K., Knai C., McKee M.. (2005) Effectiveness of interventions and programmes promoting fruit and vegetable intake: background paper for the joint FAO/WHO Workshop on Fruit and Vegetables for Health. 1–3 September 2004, Kobe, Japan. Available at http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/f%26v_promotion_effectiveness.pdf

- Rasmussen M., Krølner R., Klepp K.‐I., Lytle L., Brug J., Bere E. et al. (2006) Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among children and adolescents: a review of the literature. Part I: quantitative studies. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 3, 22 DOI: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees K., Dyakova M., Wilson N., Ward K., Thorogood M. & Brunner E. (2013) Dietary advice for reducing cardiovascular risk (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013 (3), CD002128 DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002128.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds C., Buckley J., Weinstein P. & Boland J. (2014) Are the dietary guidelines for meat, fat, fruit and vegetable consumption appropriate for environmental sustainability: a review of the literature. Nutrients 6, 2251–2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strandhagen E., Hansson P.‐O., Bosaeus I., Isaksson B. & Eriksson H. (2000) High fruit intake may reduce mortality among middle‐aged and elderly men: the study of men born in 1913. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 54, 337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinburn B.A., Sacks G., Hall K.D., McPherson K., Finegood D.T., Moodie M.L. et al (2011) The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 378, 804–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Ouyang Y., Liu J., Zhu M., Zhao G., Bao W. et al. (2014) Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: Systematic review and dose‐response meta‐analysis of prospective cohort studies. British Medical Journal 349, g4490 DOI: 10.1136/bmj.g4490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization‐Noncommunicable Diseases (NCD) Country Profiles, 2011. Available at: http://www.who.int/nmh/countries/2011/per_en.pdf (Accessed 8 September 2015)

- World Health Organization ‐ Noncommunicable Diseases (NCD) Country Profiles, 2014. Available at: http://www.who.int/nmh/countries/per_en.pdf (Accessed 8 September 2015)

- Yusof A.S., Isa Z.M. & Shah S.A. (2012) Dietary patterns and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review of cohort studies (2000–2011). Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 13, 4713–4717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Fruit and Vegetables for Health: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Workshop, 1–3 September 2004, Kobe, Japan. Available at http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/fruit_vegetables_report.pdf (Accessed 8 September 2015)