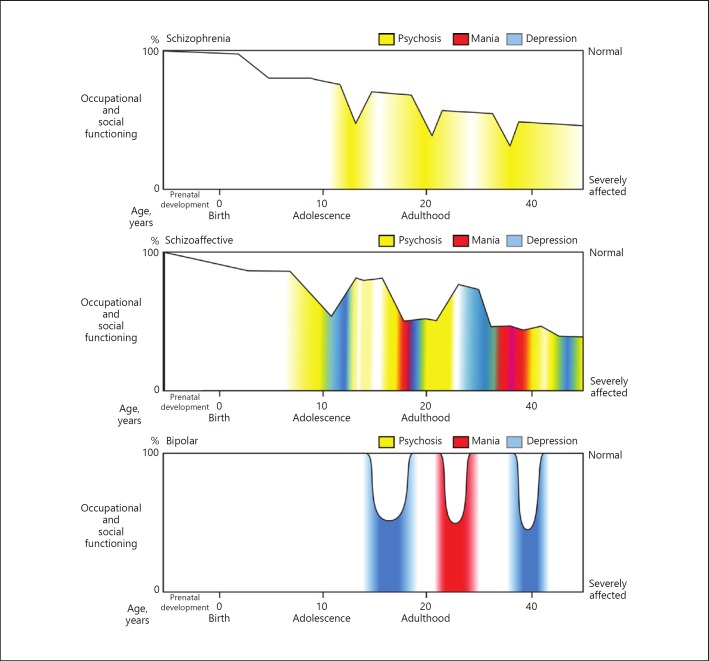

Fig. 2.

Idealized natural histories of forms of psychotic disorder. These schematics are based on simplified views of the natural histories of these disorders, originating with the ideas of Kraepelin, Bleuler, Baillarger, Falret, and Leonhard, and generally validated by longitudinal outcome studies. The broad distinction is between schizophrenia and bipolar illness. Schizophrenia is notable for subtle developmental abnormalities, detectible even in childhood. Manifest symptoms emerge in adolescence and young adulthood, with a functional and cognitive decline followed by a chronic course punctuated by episodes of more acute illness. By contrast, bipolar disorder, in its pure form, appears to involve fewer developmental abnormalities, and does not universally lead to cognitive and social decline. Instead, bipolar disorder, in its classic form, has an episodic course in which normality is interrupted by episodes of depression or mania. Many patients, however, have intermediate forms of illness, often termed schizoaffective disorder, characterized by a mixture of affective changes and psychotic phenomena, and a relatively chronic course. These three categories are oversimplifications of what is in reality a complex and heterogeneous group of diseases, which may be better described as a “spectrum” of related disorders. Nonetheless, the diagram emphasizes the importance of incorporating the natural history of the major mental illnesses, including the changes in pathophysiology that underlie changes in phenotype over the course of the disease. This concept that diseases are not static over time is one of the fundamental features of the biomedical approach to disease nosology and research, largely missing in RDoC. Illustrator: Joan M.K. Tycko.