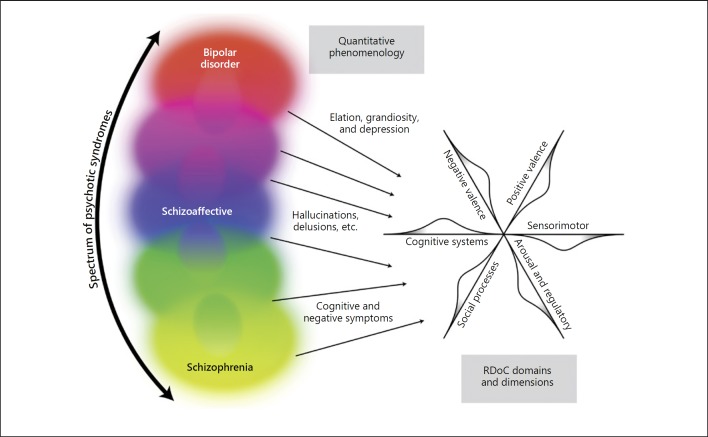

Fig. 4.

Disjunction between phenomenology of psychosis and “dimensions” of RDoC. The “spectrum” of psychosis is shown using current terminology, recognizing that both the terminology and the relationship among the various disorders will inevitably evolve in the future. Certain phenomena of this spectrum of diseases, such as delusions, hallucinations, and thought disorder, appear qualitatively distinct from normal phenomenology. Other characteristic phenomena (e.g., mood and cognition) can be measured quantitatively, and may resemble extremes of normal phenomenology. However, we argue that despite this phenomenological resemblance to extremes of normal variation, these quantitatively measurable phenomena do not necessarily correspond to the domains and constructs of the RDoC scheme (illustrated schematically as axes to show the six current RDoC domains and their dimensional nature). In our view, the phenomena of major mental illnesses represent a shift off dimensional axes of normal variation, the consequence of a breakdown in normal brain function caused by complex etiological and pathophysiological processes, and are best understood using the disease model. The main point is that even though a clinical phenomenon is quantifiable, it does not follow that such a phenomenon can best be understood as an extreme of dimensional variation along a normal axis. This line of argument also leads to the conclusion that, for disease research and clinical practice, it is better to focus attention on the quantitative phenomena observed in patients, rather than to make the a priori assumption that variations in quantitative phenomena observed in the normal population will be of direct relevance. Illustrator: Joan M.K. Tycko.