Abstract

Adenovirus (Ad) type 5 (Ad5) E4 deletion mutants including H5dl1007 (E4-) induce a DNA damage response (DDR) that activates the kinase ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM), which can interfere with efficient viral DNA replication. We find that localization of active phosphorylated ATM (pATM) to E4- viral replication centers (VRCs) is important for its inhibitory effect. ATM is necessary for localization of RNF8 and 53BP1 to E4 mutant VRCs, while recruitment of DDR factors Mre11, Mdc1 and γH2AX is ATM-independent, raising the possibility that ATM may affect viral chromatin at VRCs. We assessed E4- and Ad5 chromatin organization by micrococcal nuclease (MN) digestion. A significant fraction of Ad5 DNA is somewhat resistant to MN digestion, whereas E4- DNA is more susceptible. ATM inhibition increases the fraction of E4- DNA that is resistant to MN digestion. Our results address possible mechanisms through which ATM inhibits E4- DNA replication.

Keywords: Adenovirus, E4 ORF 3, E4 11kDa, E4 ORF 6, E4 34kDa, ATM, RNF8, 53BP1, DNA damage response, micrococcal nuclease

Introduction

Double-strand breaks (DSBs) are sensed by the Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 (MRN) complex, which activates the DNA repair kinases ATM, and ATM and Rad3-related (ATR). The DNA protein kinase (DNAPK) complex is also activated by binding of its Ku70/80 heterodimer subunits to DSBs. These kinases subsequently phosphorylate effector proteins involved in regulating DNA repair, cell cycle checkpoints, and apoptosis (reviewed in Blackford and Jackson, 2017). Activation of the DDR following ionizing radiation (IR) results in rapid accumulation of many DNA repair proteins at the site of DNA damage in distinct nuclear foci called IR-induced foci (IRIF). These foci can be readily visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy and develop through the ordered recruitment of DDR proteins (reviewed in Bekker-Jensen and Mailand, 2010). MRN, pATM, phosphorylated histone variant H2AX (γH2AX), and mediator of DNA damage checkpoint 1 (Mdc1) are examples of proteins that are found in IRIF. The MRN complex binds to ends of the broken DNA and recruits ATM (Lee and Paull, 2004). ATM is activated by auto-phosphorylation (Bakkenist and Kastan, 2003) and phosphorylates H2AX (Burma et al., 2001) to create a binding site for Mdc1 (Stucki et al., 2005). This in turn binds more molecules of the MRN complex and ATM, allowing for the spread of γH2AX modified chromatin hundreds of kilobases away from the initial site of the break (Stucki and Jackson, 2006). At DSBs, ATM also phosphorylates Mdc1 (Goldberg et al., 2003, Stewart et al., 2003) to create a docking site for ring finger protein 8 (RNF8), a ring finger-containing E3 ubiquitin ligase (Mailand et al., 2007). RNF8 recruits ring finger protein 168 (RNF168) (Stewart et al., 2009) and together they add lysine 63-linked polyubiquitin (K63Ub) chains to H2A and H2AX on damaged chromatin (Doil et al., 2009; Huen et al., 2007). The ubiquitinated histones create a docking site for repair proteins such as 53 binding protein 1 (53BP1) and breast cancer 1 (BRCA1) (Mailand et al., 2007). Recruitment of DDR proteins to IRIF is important for cell cycle checkpoint activation and repair of the damaged DNA (Bekker-Jensen and Mailand, 2010), resulting in a fully activated DDR.

Viruses deliver exogenous nucleic acid to cells. The ability of cellular DNA repair pathways to react to viral genomes can potentially either promote or interfere with the progress of viral infection. Viruses frequently manipulate DNA repair pathways by activation or inhibition to promote efficient replication and a productive infection (reviewed in Pancholi et al., 2017; Hollingworth and Grand, 2015). Since the discovery that Ad mutants lacking E4 activate DDR responses (Stracker et al., 2002; Carson et al., 2003) that result in genome concatenation (Weiden and Ginsberg, 1994; Stracker et al., 2002), there has been significant progress in deciphering the molecular mechanisms by which Ad E4 products inactivate the cellular DDR, and the impact of the DDR in interfering with E4 mutant DNA replication. Multiple Ad serotypes target DNA ligase IV to prevent genome concatenation during infection (Forrester et al., 2011; Baker et al., 2007). The MRN sensor complex is also targeted by several Ad serotypes via different mechanisms (Pancholi and Weitzman, 2018). These results indicate that the cellular DDR is an important target for Ad-mediated regulation. The interactions of subgroup C Ad5 and Ad5-derived E4 deletion mutants with cellular DDRs have been the most extensively studied. Soon after infection and the delivery of Ad DNA to the nucleus, Mre11, Mdc1, and pATM are reorganized into nuclear foci, at sites containing viral genomes (Gautam and Bridge, 2013; Karen and Hearing, 2011; Prakash et al., 2012; Prakash et al., in preparation). These observations indicate that viral genomes may trigger the recruitment of DNA repair factors in a similar fashion to their recruitment to IRIF followed DNA damage. As VRCs develop, many DDR proteins are maintained at these sites (Stracker et al., 2002; Carson et al., 2003; Gautam and Bridge, 2013), however the function of these proteins in VRCs is not known. Ad5 and E4 mutant infections both induce the accumulation of pATM in nuclear foci at early times of infection (Gautam and Bridge, 2013). However, many DDR proteins that are present in E4 mutant VRCs are not detected in Ad5 VRCs (Stracker et al., 2002; Carson et al., 2003; Gautam and Bridge, 2013), suggesting that the DDR is differentially regulated during E4 mutant and Ad5 DNA replication. The failure of Ad5 to sustain the accumulation of many DDR proteins at VRCs, is likely the result of viral early regulatory protein activity. A 34kDa protein synthesized from E4 Orf6 (E4 34kDa) forms a complex with a 55kDa viral protein expressed from E1b (E1b 55kDa) that targets several DNA repair proteins including Mre11, for proteasome-mediated degradation. An 11kDa protein from E4 Orf3 (E4 11kDa) interacts with Mre11 and redistributes it to nuclear tracks thereby preventing Mre11 association with VRCs (reviewed in Pancholi et al., 2018). These viral activities effectively interfere with activation of the cellular DDR during wild-type Ad infection (Stracker et al., 2002; Carson et al., 2003). E4 mutants that lack these regulatory proteins, activate cellular DDRs that negatively impact productive viral growth.

Activation of the DDR severely impacts E4 mutant DNA replication (Evans and Hearing, 2003; 2005; Mathew and Bridge, 2007; 2008; Lakdawala et al., 2008; Gautam and Bridge, 2013, Shah and O’Shea, 2015). Cells that lack a functional MRN complex substantially rescue E4 mutant growth defects (Evans and Hearing, 2005; Lakdawala et al., 2008; Mathew and Bridge, 2007; 2008). Furthermore, we and others have shown that activated ATM kinase interferes with E4 mutant DNA replication (Gautam and Bridge, 2013; Shah and O’Shea, 2015), suggesting that MRN may inhibit viral DNA replication at least in part through its ability to activate ATM. The mechanism of ATM-mediated inhibition of E4 mutant DNA replication is currently unknown. ATM is activated by the MRN complex that binds and recruits the kinase to the site of DSBs. Cells that lack Nbs1 are defective for ATM activation (Cerosaletti et al., 2006). Recruitment of ATM to the damage site and its activation requires its association with the C-terminal ATM binding domain in the Nbs1 protein (Falck et al., 2005; You et al., 2005). It is also known that E4 11kDa-mediated redistribution of Mre11 is sufficient to allow close to normal levels of Ad DNA replication in mutants that lack a functional E4 34kDa/E1b 55kDa complex (Evans and Hearing, 2005), despite the observation that such mutants still activate ATM (Carson et al., 2009). Since a functional MRN complex is required to recruit ATM to DSBs, this raises the possibility that E4 11kDa promotes viral DNA replication by preventing activated pATM from localizing to VRCs.

Previous studies have indicated that recruitment of the MRN complex to VRCs is correlated with inhibition of E4 mutant DNA replication (Mathew and Bridge, 2007; 2008). However, recruitment of Mre11 was not sufficient to inhibit E4 mutant DNA replication in the absence of activated ATM (Gautam and Bridge, 2013). Several studies have shown that ATM activation is required for recruitment of downstream DDR proteins and chromatin remodeling factors to DSBs (reviewed in Price and D’Andrea, 2013). ATM could inhibit E4 mutant DNA replication by recruiting additional DDR factors and/or chromatin remodeling complexes to viral chromatin, and possibly prevent the ability of viral proteins to access the terminally located origin of replication. Here, we have studied the localization of ATM and other DDR proteins to Ad VRCs as well as the chromatin organization of Ad5 and E4- DNA ends, to further investigate the mechanism of ATM-mediated inhibition of E4- DNA replication. Our results indicate that failure to localize activated pATM to E4- VRCs is correlated with increased viral DNA replication. Some DDR proteins, including γH2AX, Mre11, and Mdc1, were recruited to VRCs independently of ATM, and were not sufficient to interfere with viral DNA replication in the absence of ATM. In contrast, other DDR proteins such as RNF8 and 53BP1 were not found in E4- VRCs in the absence of pATM. When we examined viral chromatin by micrococcal nuclease (MN) digestion, Ad5 and E4- showed a similar pattern of MN protected fragments. The digestion pattern was different from the typical nucleosome organization seen for the cellular β-actin gene. However, a significant fraction of Ad5 DNA was undigested and somewhat resistant to MN treatment, while E4- DNA was relatively sensitive. Interestingly, treatment with an ATM inhibitor rescued E4- DNA replication, and also significantly increased the MN resistant fraction. This suggests that the MN resistant fraction could correspond to viral DNA protected in VRCs.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and viruses

HeLa and E4 mutant-complementing W162 cells (Weinberg and Ketner, 1983) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Fisher) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10 U/ml penicillin and 10 μg/ml streptomycin. Fibroblast cell lines that lack the ATM gene (GM16666, referred to here as ATM−) and lines that have normal ATM expression (GM00637, referred to here as ATM+) were purchased from the Coriell cell repository. These cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 10 U/ml penicillin, 10 μg/ml streptomycin. In some experiments the ATM inhibitor KU60019 (Tocris) (dissolved in DMSO) was added to the culture at 2 hpi to a concentration of 5 μM for the time indicated. Wild type Ad5, E4 mutant H5dl1007 (referred to here as E4-) and E4 mutant H5dl1010 (referred to here as dl1010) (Bridge and Ketner, 1989) viral stocks were prepared on W162 cells. Virus titers were measured on W162 cells according to (Philipson, 1961) and expressed as fluorescence forming units/ml (FFU/ml).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Immunofluorescence microscopy was performed as previously described (Gautam and Bridge, 2013) for all double immunostainings using two primary antibodies. For triple immunostaining, three primary antibodies generated in different species were incubated with the fixed cells for 1 h. After washing 3 times for 5 min each with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (Tris-buffered saline; 100 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl), and rinsing once with TBST (Tris-buffered saline Tween; 100 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20), donkey anti-mouse and donkey anti-goat secondary antibodies were incubated for 45 min. The cover glasses were then washed 3 times for 5 min each in TBS and cross-linked with 4% PFA in PBS (0.058 M Na2HPO4, 0.017 M NaH2HPO4, 0.069 M NaCl) to prevent cross reaction between secondary antibodies. Cover glasses were again washed 3 times for 5 min each in TBS prior to incubation with goat anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 405 IgG. After washing with TBS cover glasses were placed in mounting medium on a microscope slide and sealed with nail polish.

Primary antibodies were used for immunofluorescence microscopy at the dilutions indicated: goat polyclonal anti-Mre11 (Santa Cruz) (1:100), rabbit polyclonal anti-Mdc1 (Bethyl) (1:100), mouse monoclonal anti-γH2AX (Abcam) (1:200), mouse monoclonal B6–10 anti-72K (a gift from A. Levine) (1:100), rabbit polyclonal anti-72K (a gift from T. Linné) (1:1500), mouse monoclonal anti-pATM kinase (phospho epitope S1981, Novus) (1:200), rabbit polyclonal anti-RNF8 (Abcam) (1:30), rabbit polyclonal anti-53BP1 (Abcam) (1:100). Secondary antibodies from Invitrogen were used for immunofluorescence at the indicated dilutions: goat anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 405 IgG (1:250), donkey anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 594 IgG (1:250), donkey anti-mouse AlexaFluor 488 IgG (1:250), donkey anti-goat AlexaFluor 594 IgG (1:250).

A confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus FV500) was used to capture images with Fluoview software. Alexa 405, Alexa 488 and Alexa 594 channels were scanned sequentially to prevent bleed through between the channels. Images were assembled into figures using Adobe Photoshop CS5 extended software.

Micrococcal Nuclease (MN) Digestion in isolated nuclei

Nuclei were prepared and MN digestion was performed using the Zymo Research EZ Nucleosomal DNA Prep Kit, following instructions provided by the manufacturer. Briefly, 8 ×106 infected or uninfected HeLa cells were washed twice in ice-cold PBS and then scraped into 1ml of PBS. Some cultures were incubated with formaldehyde added to culture medium to a final concentration of 1% at room temperature for 15 minutes, and quenched with the addition of glycine to 125mM for 1 min, prior to washing and scraping the cells. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 1,400 × g for 1 minute. The supernatant was removed and cells were resuspended in a 1:1 mixture of Nuclei Prep Buffer and MN Digestion Buffer, incubated on ice for 5 minutes to extract the cytoplasm, and the nuclei were then pelleted by centrifugation. The nuclei were washed and resuspended in MN Digestion Buffer. Samples with ~ 2 × 106 nuclei were incubated with 0.1 (1X), 0.2 (2X), or 0.3 (3X) units of MN, and incubated at 4°C, 10°C or room temperature for 15 or 30 minutes. The digestion was stopped using Zymo MN Stop Buffer. Total DNA was then prepared from the nuclei as described below.

DNA Preparation

Total DNA from infected and uninfected cells or nuclei was prepared as previously described (Gautam and Bridge; 2013). Briefly, cells or nuclei were lysed in 1X Proteinase K buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS), digested with 0.4mg/ml proteinase K at 42°C overnight. Samples were extracted with phenol and chloroform to remove digested proteins. Samples were treated with 0.25 mg/mL RNase A for 1 hour at 37°C to digest the RNA, and following phenol chloroform extraction, DNA was precipitated with ethanol and resuspended in H2O. 10 – 20 μg of total DNA prepared as described was fractionated on 1.5% agarose gels and subsequently analyzed by Southern blotting.

Southern Blotting

Agarose gels were washed in denaturation solution (1.5 M NaCl, 0.5 M NaOH) for 30 minutes at room temperature. The gels were washed twice for 15 minutes at room temperature in neutralization solution (1.5 M NaCl, 0.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.2), 1 mM EDTA). DNA transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Hybond-NX-GE Life Sciences) was performed as described (Sambrook et al., 1989). After drying the membrane, the DNA was cross-linked to the membrane using a Fisher Scientific UV crosslinker at 120,000 μJ/cm2. The membrane was blocked for at least 2 hours at 65°C with pre-hybridization solution 6X SSC (0.9 M NaCl, 0.09 M sodium citrate), 5X Denhardt’s solution (100X (from VWR), 0.5% SDS) containing 75 μg/ml of denatured salmon sperm. Probes used were random primed PCR products corresponding to sequences overlapping the Ad left inverted terminal repeat (ITR) or the cellular β-actin gene. PCR primers for the ITR probe corresponded to (Forward: 5’ GGA TTG AAG CCA ATA TGA TAA TGA GG, Reverse: 5’ GTC TCC ACG TAA ACG GTC AAA GTC C). PCR primers for the β-actin exon 4 probe corresponded to (Forward: 5’ GAA GGA AGG CTG GAA GAG TGC C, Reverse: 5’ AGC CAT GTA CGT TGC TAT CCG). Viral or cellular DNA was amplified with these primers using a Taq PCR Core Kit (Qiagen) to generate template DNA for the random priming reaction. P32- labeled dCTP was incorporated into a random priming reaction (Takara Random Primer DNA Labeling Kit Version 2) with 100 ng of gel purified Ad ITR or β-actin PCR products. Radioactive probes were separated from unincorporated radioactive nucleotide using a 1 ml column of Sepharose G-50 beads suspended in 1X TE (10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA). The column was packed by centrifugation (Sorvall RT6000B) at 1000 rpm for 1 minute at 4°C. To purify the radioactive probes, 150 μl distilled water was added to the random priming reaction, and the contents were then loaded onto the packed G-50 column and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 3 minutes at 4°C, to elute the radioactive random primed probe fragments. The specific activity of the probes was typically ~ 1 × 109 cpm/μg. The probes generated from the random priming reaction were heated to 100°C for 5 minutes and chilled immediately on ice. Blots were incubated with 1 × 106 cpm/ml of ITR or β-actin probe for hybridization overnight at 65°C. The membrane was washed twice in low stringency buffer (2x SSC, 0.1% SDS) at room temperature for 10 minutes each wash, and twice with high stringency buffer (0.1x SSC, 0.1% SDS) at 65°C for 10 minutes each wash. The dried membrane was then exposed to autoradiography film and developed. Densitometry was performed using ImageJ software, version 1.52a.

Results

Localization of activated pATM to VRCs is important for inhibiting E4- DNA replication

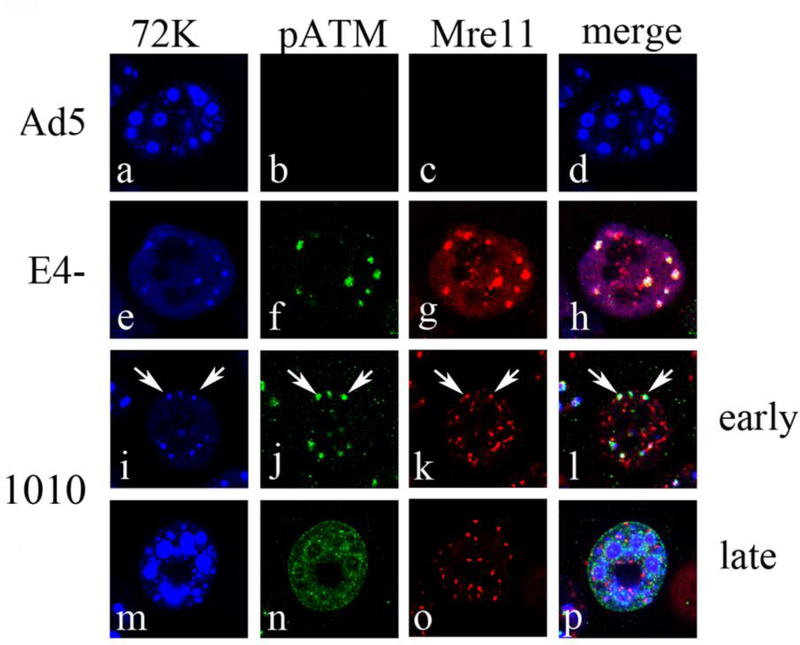

We have previously shown that the kinase ATM is important for interfering with E4 mutant DNA replication (Gautam and Bridge, 2013). E4 mutant dl1010 carries a deletion affecting the E4 34kDa Orf 6 gene (Bridge and Ketner, 1989), which is important for promoting degradation of multiple cellular factors, including the DDR protein Mre11 (Carson et al., 2003). However, dl1010 expresses E4 11kDa from an intact Orf 3 gene, and can redistribute Mre11 into nuclear tracks and cytoplasmic aggresomes, thereby preventing its localization at VRCs (Carson et al., 2003; Prakash et al., 2012; Araujo et al., 2005). It was shown previously that E4 11kDa is sufficient to promote efficient viral replication in mutants that fail to express E4 34kDa (Bridge and Ketner, 1989; Evans and Hearing, 2005), despite the observation that dl1010 and a similar Orf 6 mutant efficiently activate ATM (Prakash et al, in preparation; Carson et al., 2009). Since activated ATM inhibits DNA replication in E4 mutants that lack both E4 34kDa and E4 11kDa (Gautam and Bridge, 2013), we hypothesized that E4 11kDa mediated Mre11 redistribution might prevent pATM localization to VRCs in dl1010 infections, thereby preventing the inhibitory effect of pATM on viral DNA replication. We analyzed the localization of pATM relative to VRCs during dl1010 infections to address this hypothesis. The status of the 11kDa and 34kDa genes in the viruses studied is shown in Table 1. HeLa cells were infected with Ad5, E4-, or dl1010 at an MOI of 3FFU/cell for 17 h, and then fixed and immunostained with anti-72K, anti-pATM and anti-Mre11 (Fig. 1). During infections with Ad5, pATM staining was not detected in most cells and VRCs were well developed with no detectable Mre11 staining (Fig. 1 panels a to d). In contrast, pATM staining was consistently observed in E4- infections where it co-localized with poorly developed VRCs along with Mre11 (Fig. 1 panels e to h). During Ad infection VRCs are initially observed as small foci containing the viral 72K protein, that become larger and pleomorphic in shape as infection progresses. We have previously determined that by 17hpi at MOI 3 nearly 80% of cells in the Ad5 infected culture have large 72K centers. By contrast, less than 5% of cells in E4- infected cultures contained large 72K centers, while 65% of cells contained small 72K foci (Gautam and Bridge, 2013). We were able to detect some early phase dl1010 infected cells with small 72K foci; some of these foci still co-localized with both pATM and Mre11 suggesting that when Mre11 is localized to VRCs, pATM is also present there (Fig. 1 panels i to l, see arrowheads). In the majority of dl1010 infected cells 72K centers were large and similar to Ad5, indicating that the cells were in the late phase and had undergone significant DNA replication. In these cells Mre11 was completely redistributed into track like structures and pATM no longer closely colocalized with either 72K or Mre11 (Fig. 1, panels m to p). When viral DNA levels were measured by Southern blotting, dl1010 DNA levels were similar to Ad5 while E4- DNA levels were about 5-fold reduced (Table 1). The data indicate that dl1010 fails to sustain the localization of pATM at VRCs compared to E4- infections. This is correlated with an increase in the size of VRCs (Fig. 1, panels m to p), and the levels of viral DNA measured by Southern blotting (Table 1), in dl1010 vs. E4- infected cells. These results suggest that activated ATM may only interfere with viral DNA replication when it is associated with VRCs.

Table 1.

Status of the E4 11-kDa and 34-kDa genes and DNA replication phenotypes in the viruses studied.

| Virus | E4-11kDa gene status (E4 ORF3) | E4-34kDa gene status (E4 ORF6) | DNA replication* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ad5 | + | + | 1 |

| E4- | − | − | 0.19 |

| 1010 | + | − | 0.84 |

Measured by Southern blotting of total DNA prepared from cells infected at an MOI of 3FFU/cell. Values are expressed as the fraction of the Ad5 value as determined by densitometry.

Figure 1. pATM does not colocalize with VRCs in dl1010 infections.

HeLa cells were infected with Ad5, E4-, or dl1010 at 3FFU/cell. At 17 hpi cells were fixed and stained with anti-pATM (phosphoepitope S1981), anti-Mre11 and anti-E2 72kDa antibodies. Immunofluorescence confocal micrographs showing E2 72kDa (72K) in blue, pATM in green, Mre11 in red, and merged staining patterns are presented. Cells with early and late stage replication centers were identified based on size of E2 72kDa foci. Arrows indicate the location of 72K centers that are still colocalized with Mre11 and pATM in early stages of viral infection.

Differential recruitment of DDR proteins to VRCs in the presence and absence of ATM

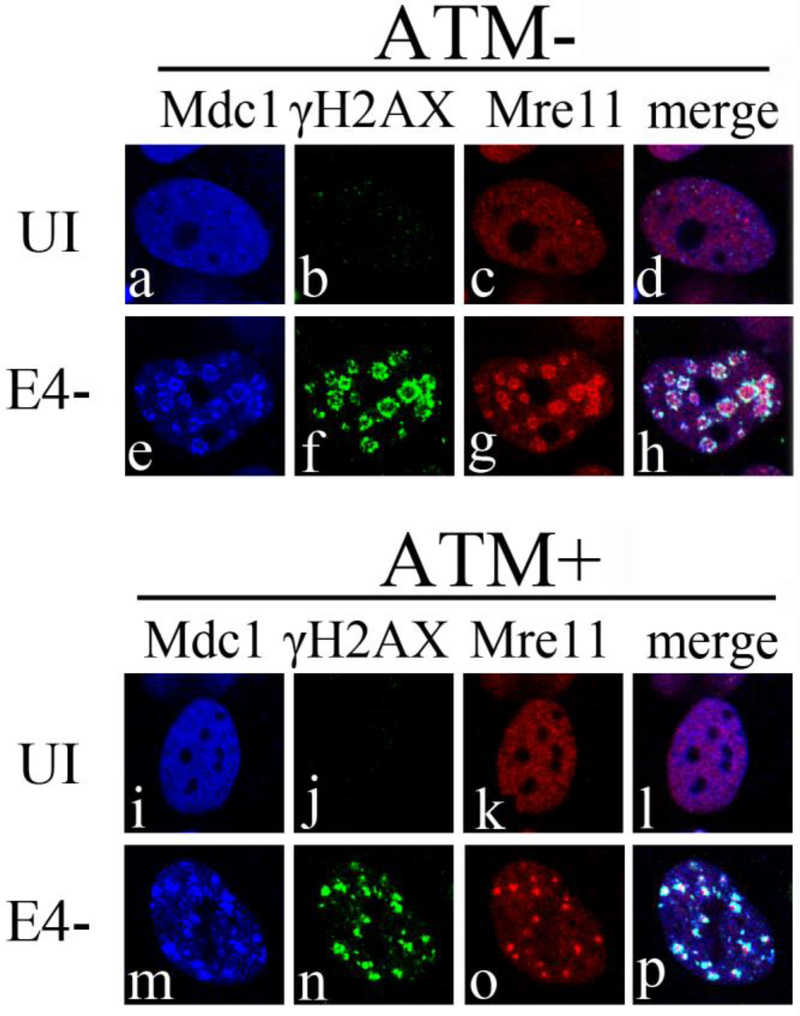

Several DDR proteins are recruited to sites of DNA damage (Bekker-Jensen and Mailand, 2010) as well as to E4 mutant VRCs (Carson et al., 2003; Stracker et al., 2002). Recruitment of these DDR proteins occurs in a temporal manner with Mre11, Mdc1 and γH2AX, recruited rapidly to the site of DNA damage (Bekker-Jensen and Mailand, 2010). Previously it has been suggested that binding of Mre11 to the viral genome might block access of the viral replication machinery to the origin of replication and hence inhibit DNA replication (Mathew and Bridge, 2008; Karen and Hearing, 2011). However, we have reported that recruitment of Mre11 to E4- VRCs is not sufficient to inhibit E4-DNA replication in absence of ATM or its kinase activity (Gautam and Bridge, 2013). Since Mre11 recruitment alone was not sufficient to inhibit E4- DNA replication, we determined if other early DDR proteins such as Mdc1 and γH2AX were localized with Mre11 during E4- infection in the presence and absence of ATM. ATM− and ATM+ cells were either uninfected or infected with E4- at an MOI of 3 FFU/cell and fixed at 17 hpi. Cells were then immunostained with anti-Mre11, anti-Mdc1 and anti-γH2AX antibodies. Confocal immunofluorescence micrographs are presented in Fig. 2. Since Mre11 is colocalized with E4- VRCs independent of activated ATM throughout infection (Gautam and Bridge, 2013), we used localization of Mre11 as a marker to represent sites of DNA replication. γH2AX and Mdc1 were recruited to VRCs containing Mre11 (Fig. 2, panels e to h and m to p) in both E4- infected ATM− and ATM+ cells. These results suggest that the early DDR proteins Mre11, γH2AX and Mdc1 are recruited to E4- VRCs irrespective of the presence or absence of ATM. Since E4- DNA replication is substantially rescued in ATM− cells (Gautam and Bridge, 2013), our data indicate that the recruitment of these early DDR proteins to VRCs is not sufficient to inhibit E4- DNA replication in the absence of ATM.

Figure 2. Mdc1 and γH2AX colocalize with Mre11 at E4- VRCs independent of ATM.

ATM+ and ATM− cells were infected with E4- at an MOI of 3 FFU/cell. At 17 hpi cells were fixed and immunostained with antibodies against Mdc1, γH2AX and Mre11. Immunofluorescence confocal micrographs show Mdc1 (blue), γH2AX (green), Mre11 (red), and merged staining patterns of uninfected (UI) or E4- infected cells.

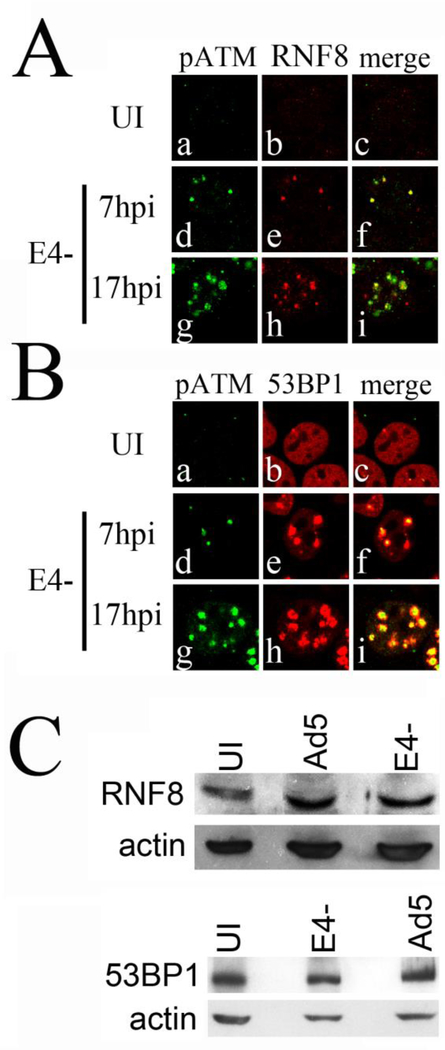

DDR proteins such as RNF8 and 53BP1 are recruited to DSBs following IR in a manner that depends on ATM induced chromatin modification in the vicinity of the DNA break. Activated pATM phosphorylates Mdc1, which in turn recruits RNF8, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, which adds polyubiquitin to γH2AX (Mailand et. al, 2007; Stewart et al., 2009; Doil et al., 2009; Huen et al., 2007). This is important for localization of DDR proteins such as 53BP1 and BRCA1 to the DSB (Mailand et al., 2007). We determined if RNF8 and 53BP1 were present at VRCs containing pATM in E4- infections. HeLa cells were uninfected or infected with E4-, fixed and immunostained at 7 and 17 hpi with anti-pATM and anti-RNF8 or anti-53BP1. Confocal micrographs of representative staining patterns are presented in Fig. 3. We found that RNF8 and 53BP1 were present with pATM at VRCs during E4- infections at both 7 hpi and 17 hpi (Fig. 3A and B). RNF8 and 53BP did not localize to VRCs in Ad5 infections (data not shown) as expected since Ad5 VRCs lack pATM (Gautam and Bridge, 2013). Although RNF8 appeared more visible by immunofluorescence in E4- infections, western blotting revealed similar levels of RNF8 and 53BP1 in Ad5, E4- infected, and uninfected cells Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. RNF8 and 53BP1 are recruited to pATM containing E4- VRCs.

HeLa cells were uninfected or infected with E4-, and at 7 and 17 hpi cells were fixed and immunostained with anti-pATM (phosphoepitope S1981) and anti-RNF8 (A) or 53BP1 (B) antibodies. Immunofluorescence micrographs showing pATM (green), RNF8 or 53BP1 (red), and merged staining patterns are presented. UI, uninfected cells. (C) Western blot showing levels of the RNF8 and 53BP1 proteins in uninfected (UI), Ad5 and E4- infected cells. Levels of β-actin in the samples were measured as a control.

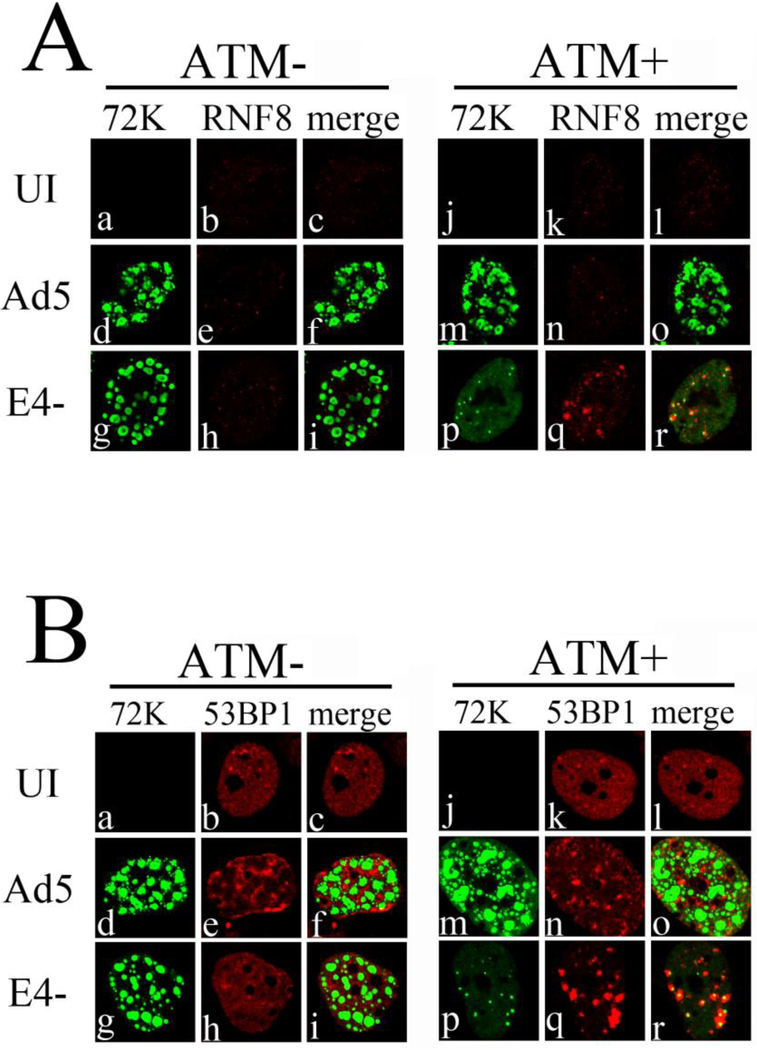

Since RNF8 and 53BP1 colocalized with pATM in E4- infections, we tested if RNF8 and 53BP1 were localized to VRCs in an ATM dependent manner. ATM− and ATM+ cells were infected with E4- or Ad5 at MOI 3FFU/cell for 17 h and cells were fixed and immunostained with anti-E2 72kDa to label VRCs, and either anti-RNF8 or anti-53BP1 antibodies. The results are presented in Fig. 4. In ATM+ cells RNF8 and 53BP1 colocalized with poorly developed VRCs in E4- infections (Fig. 4 A and B panels p–r), while in Ad5 infected cells RNF8 and 53BP1 were not detected in VRCs (Fig. 4 A and B panels m–o). Interestingly, during E4- infections in ATM− cells, both RNF8 and 53BP1 failed to localize with VRCs (Fig. 4 A and B panels g–i), similar to wild type Ad5 (panels d-f). E4- VRCs were much larger in the absence of ATM as expected (Gautam and Bridge, 2013). Our results indicate that while ATM is not required for recruitment of Mre11, Mdc1 or γH2AX to E4- VRCs, it is required to recruit DDR proteins RNF8 and 53BP to these sites.

Figure 4. Localization of RNF8 and 53BP1 to E4- VRCs requires ATM.

ATM+ and ATM− cells were infected with E4- and Ad5 viruses at an MOI of 3 FFU/cell for 17 h. Cells were then fixed and immunostained with antibodies against the viral DNA binding protein E2 72kDa (72K) and RNF8 (A) or 53BP1 (B). Immunofluorescence confocal micrographs show E2 72kDa (green), RNF8 or 53BP1 (red), and merged staining patterns of uninfected (UI), Ad5, or E4-infected cells.

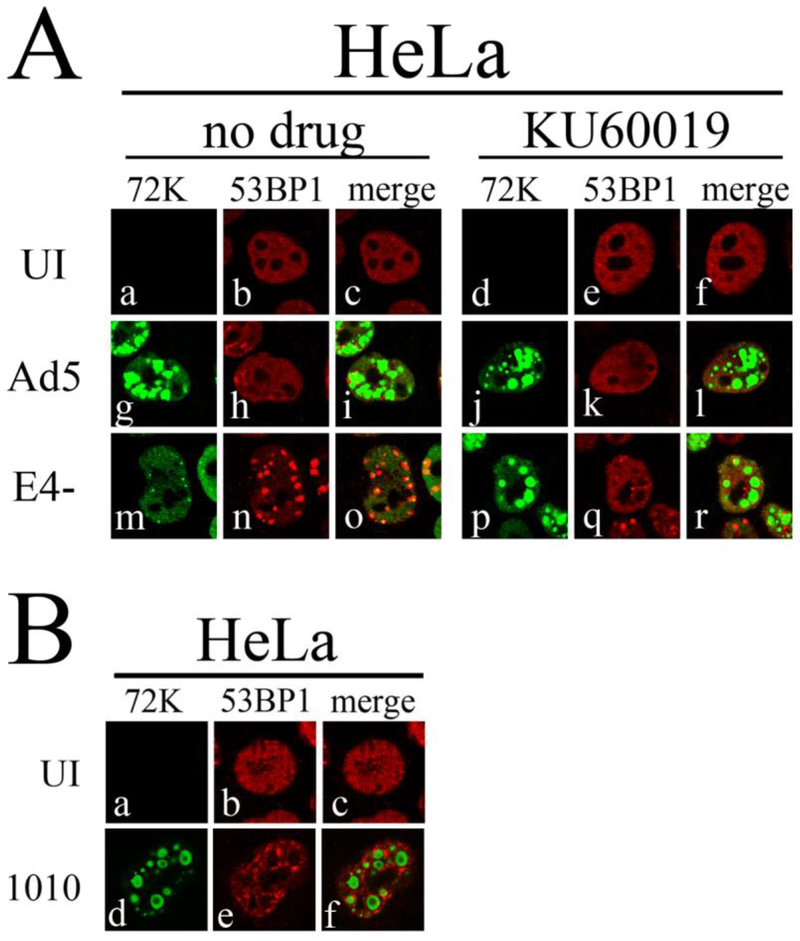

Failure to localize activated pATM to E4- VRCs prevents localization 53BP1 to these sites

53BP1 localization to DSBs depends on ubiquitination of H2A and H2AX, and is thus sensitive to ATM-mediated chromatin modifications in the vicinity of the break (Mailand et al., 2007). Since recruitment of 53BP1 to VRCs may depend on ATM-dependent modification of viral chromatin, we investigated the requirements for 53BP1 recruitment to VRCs. We first determined if active ATM was important for 53BP1 localization to VRCs. Treatment of HeLa cells with KU60019 prevents the accumulation of pATM at E4- DNA VRCs although unphosphorylated ATM is still present at these sites (Gautam and Bridge, 2013). We tested if 53BP1 localization to E4- VRCs was also affected by KU60019 treatment. HeLa cells were uninfected or infected with E4- and Ad5 at an MOI of 3 FFU/cell and at 2 hpi cells were either treated with the solvent DMSO or with KU60019. At 17 hpi cells were fixed and immunostained with anti-72K and anti-53BP1 antibodies. Confocal immunofluorescence micrographs are presented in Fig. 5A. Ad5 infected cells treated with or without KU60019 showed no 53BP1 colocalization with VRCs. During E4- infection in absence of the drug, 53BP1 was colocalized with VRCs as expected. However, in presence of KU60019, 53BP1 was not detected in E4- VRCs. The results suggest that localization of 53BP1 to VRCs requires activated ATM kinase. We next investigated 53BP1 localization in dl1010 infections that activate pATM but fail to recruit it to VRCs. HeLa cells infected with dl1010 for 17 h were immunostained with anti-53BP1 and anti-72K antibodies. Confocal immunofluorescence micrographs (Fig. 5B) show that 53BP1 does not localize with the well-developed VRCs that were previously shown to lack pATM (Fig. 1). The data indicate that 53BP1 recruitment to VRCs requires active pATM that is also localized to VRCs.

Figure 5. Failure to localize pATM to VRCs results in inefficient recruitment of 53BP1.

(A) HeLa cells were uninfected (UI), or infected with Ad5 or E4-. The ATM inhibitor KU60019 (5μM) or DMSO was added to the medium at 2 hpi, and cells were fixed and stained for immunofluorescence at 17 hpi. Immunofluorescence confocal micrographs showing E2 72kDa (green), 53BP1 (red), or merged staining patterns are shown. (B) HeLa cells were uninfected or infected with dl1010 for 17 h and cells were prepared for immunostaining with anti-72K and anti-53BP1 antibodies. Immunofluorescence confocal micrographs showing E2 72kDa (green), 53BP1 (red), or merged staining patterns are shown.

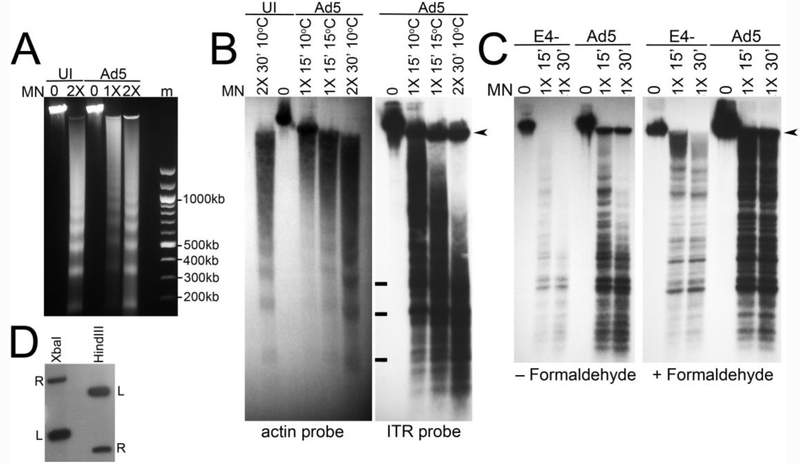

Chromatin organization of viral DNA during E4- and Ad5 infections

ATM is known to modify chromatin in the vicinity of DNA breaks (Price and D’Andrea, 2013). Since the linear double stranded Ad genome may mimic a DNA break, it is possible that ATM modifies viral chromatin in the vicinity of the genome ends when it is active. This could potentially impact viral DNA replication because the origin of replication is located at the ends of the viral genome within the inverted terminal repeat. We examined chromatin organization at the ends of the viral genome by measuring the sensitivity of this region to digestion by MN. HeLa cells were either uninfected or infected with Ad5 or E4- at 3 FFU/cell and harvested at 17 hpi. Nuclei were isolated and then were either untreated, or subjected to MN treatment. Total DNA was prepared and analyzed by Southern blotting using a probe that overlaps the 5’ inverted terminal repeat (ITR) or a probe corresponding to exon 4 of β-actin. MN treated DNA samples demonstrated a typical nucleosome ladder after fractionation of total DNA on an agarose gel and ethidium bromide staining (Fig. 6A). Southern blot analysis of these samples with the β-actin probe indicated that the β-actin gene was organized in nucleosomes as previously described (Jeong and Stein, 1994) (Fig. 6B left panel). Interestingly, when the blots were labelled with the Ad5 ITR probe we saw a series of protected fragments, but they did not completely correspond to the protected fragments of the nucleosome ladder. Bands that could correspond to 1, 2 and 3 nucleosomes are indicated, but several additional MN cleavage products are observed in the ITR probed samples compared to the β-actin probed samples (Fig. 6B). This raises the possibility that Ad DNA ends are not tightly organized in a typical nucleosome pattern. We observed a similar profile of MN protected fragments in E4- DNA samples (Fig. 6C left panel), although the labeling intensity was reduced as expected since E4- shows reduced DNA replication under these infection conditions (Table 1). We also measured the MN protection pattern in Ad5 and E4- infected cells that were fixed in formaldehyde to stabilize the chromatin configuration prior to MN digestion. These samples showed a similar banding pattern following Southern blot analysis of MN digested DNA, however the bands were sharper and more distinct (Fig. 6C right panel). We performed a Southern blot analysis of XbaI and HindIII cut DNA prepared from Ad5 infected cells to make sure our ITR probe only labelled the expected terminal fragments. The results shown in Fig. 6D indicate that in both digests, the expected left and right terminal fragments of the genome were detected by the probe. The left terminal fragments labelled more intensely than the right terminal fragments as expected, since the probe corresponds to nucleotides 26 – 384 of the left terminus of the genome. However, because the repeat sequence is also present in the right terminus, the probe also detects right terminal fragments.

Figure 6. Analysis of viral chromatin by MN digestion.

HeLa cells were infected with Ad5 or E4- at 3 FFU/cell. Nuclei were prepared and treated with MN as indicated, followed by preparation of total DNA from each sample. (A) Ethidium bromide stained gel showing nucleosome protected DNA prepared from uninfected (UI) and Ad5 infected cells. Samples were incubated with MN at the indicated amounts for 30 min at 10°C. (B) Southern blot analysis of MN digested DNAs. Samples were run on the same gel, and after transfer the membrane was cut and separately hybridized to radiolabeled β-actin (left panel) or Ad ITR probe (right panel) as indicated. The positons of bands corresponding to DNA protected by 1, 2 and 3 nucleosomes are marked with a bar. The arrowhead indicates the position of viral DNA that was not digested by MN treatment. (C) Southern blot analysis of MN treated DNA from Ad5 and E4- infected cells. Samples were treated with MN for the indicated amounts and times at 4°C. Some samples were fixed with formaldehyde prior to MN digestion as indicated. The arrowhead indicates the position of viral DNA that was not digested by MN treatment. (D) Southern blot analysis of Hind III and XbaI digested Ad5 DNA hybridized with the radiolabeled ITR probe. The probe labeled only the left (L) and right (R) terminal fragments in both digests. Sizes of the left and right terminal fragments are 1339 bp and 5469 bp for the XbaI digest, and 2804 bp and 1008 bp for the HindIII digest.

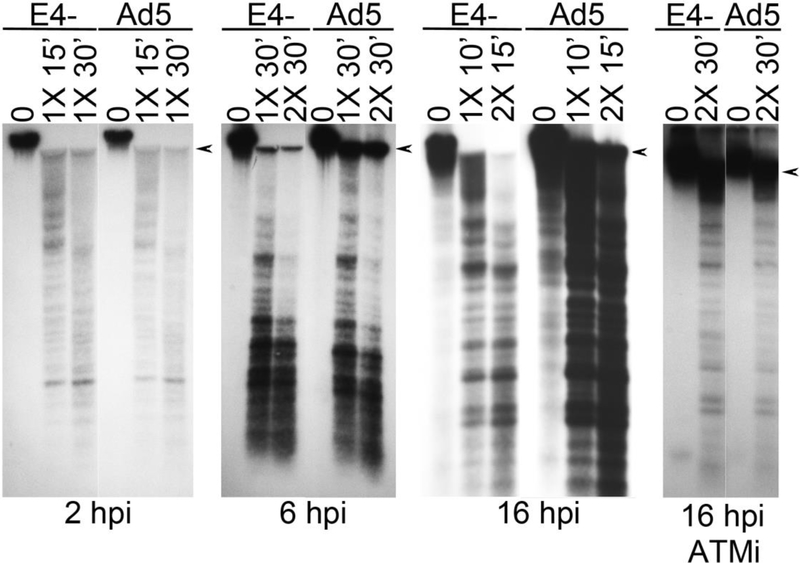

We next performed an analysis of the chromatin organization of viral genome ends in Ad5 and E4- infections at different time points. Cells were infected with the indicated virus for 2, 6 or 16h, fixed with formaldehyde, and then isolated nuclei were treated with MN as described in materials and methods. Total DNA was then prepared, fractionated on an agarose gel and analyzed by Southern blotting using the Ad5 ITR probe (Fig. 7). At 2 and 6hpi Ad5 and E4- DNA levels were similar in samples that were not treated with MN, indicating that similar levels of input virus were delivered to the cell prior to the onset of DNA replication. MN treatment resulted in a similar digestion pattern for both E4- and Ad5 at all three time points tested. Interestingly, by 6hpi wildtype Ad5 DNA was somewhat resistant to MN treatment, as indicated by the fraction of the high molecular weight DNA hybridizing to the ITR probe that remained undigested (marked with an arrowhead). In contrast, most of the high molecular weight DNA was digested in the E4- sample. Similar results were seen at 16hpi. At this time point Ad5 DNA levels were higher than E4-, consistent with the observation that E4 mutants have a DNA replication defect at this time point (Table 1). Although the MN protected fragments were less intense in the E4- samples because of the reduction in DNA levels compared to Ad5 at this time point, nevertheless the banding pattern of the lower molecular weight protected fragments was similar between the two viruses. In contrast, Ad5 showed a significantly higher fraction of nuclease resistant high molecular weight DNA than was detected in E4- samples. Densitometry revealed that the Ad5 MN resistant high molecular weight fraction in the 2X MN treated sample was about 49% of the input undigested sample, while the E4- resistant DNA fraction of the 2X MN treated sample was about 4%, at 16 hpi.

Figure 7. Analysis of MN digested viral chromatin at different time points.

HeLa cells were infected with Ad5 or E4- at 3 FFU/cell. Some cultures were treated with the ATM inhibitor KU60019 at 5 μM from 2 to 16hpi. Cells were fixed in formaldehyde and nuclei were prepared and treated with MN as indicated at 4°C, or at room temperature for 16hpi samples that were not treated with ATM inhibitor, followed by preparation of total DNA from each sample. DNA samples were then analyzed by Southern blotting using radiolabeled ITR probe. Arrowheads indicate the position of viral DNA that was not digested by MN treatment.

We examined the impact of ATM inhibition on the MN digestion pattern of E4- and Ad5 infected cells at 16hpi. Treatment with the ATM inhibitor KU60019 restored E4- DNA levels to those of Ad5 as expected (Gautam and Bridge, 2013), but did not dramatically affect the MN digestion pattern compared to untreated samples. The level of viral DNA in the high molecular weight resistant fraction was similar in Ad5 and E4-samples prepared from KU60019 treated cells (densitometry of a lighter exposure indicated 51% and 60% of the undigested sample, respectively). This suggests that the high molecular weight MN resistant fraction may be associated with efficient E4- DNA replication in the absence of functional ATM.

Discussion

We have previously reported that activated pATM interferes with Ad E4 mutant DNA replication (Gautam and Bridge, 2013). However, the mechanism by which ATM inhibits viral DNA replication is still unclear. Activated pATM could inhibit E4 mutant DNA replication by physically localizing to the viral DNA. Indeed, previous work has shown that pATM co-localizes with input E4 mutant viral genomes (Karen and Hearing, 2011) as well as at VRCs (Carson et al., 2003). In dl1010 infections the E4 11kDa protein is produced and redistributes Mre11 to nuclear tracks such that it fails to localize with VRCs (Fig. 1). Mislocalization of Mre11 by E4 11kDa does not prevent ATM activation in response to an Ad infection (Carson et al., 2009; Prakash et al., in preparation), but interestingly, we find that it does prevent the sustained localization of activated pATM at dl1010 VRCs (Fig. 1). Furthermore, loss of pATM co-localization correlates with robust growth of dl1010 VRCs. Our data are consistent with a scenario in which the MRN complex is important both for activating pATM, and localizing it to VRCs. These roles are important for the ability of pATM to inhibit E4- DNA replication, and support a model where the ATM kinase inhibits E4- DNA replication when it is physically localized to VRCs.

In contrast to earlier findings (Carson et al., 2003), Shah and O’Shea (2015) have reported activation of ATM in wild-type Ad5 infections. We have not detected high levels of pATM in Ad5 infections by western blotting (Gautam and Bridge 2013; Prakash et al., in preparation), consistent with more recent results published by the Weitzman group (Pancholi and Weitzman, 2018). Although we have seen diffuse pATM localization in a subset of Ad5 infected cells by immunofluorescence, similar to the diffuse pATM localization observed in late phase Ad5 infected cells by Shah and O’Shea (2015), in our experiments this signal was not reduced by the ATM inhibitor KU60019 (data not shown but discussed in Gautam and Bridge, 2013). ATM inhibition does not significantly affect Ad5 DNA replication (Gautam and Bridge, 2013; Shaw and O’Shea 2015), suggesting that when pATM is not retained at VRCs, it does not have an inhibitory affect on DNA replication. The observation that ATM is bound to the DNA of a replication defective E1b55K/E4orf 3 double mutant, but not to wild-type Ad5 in chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments (Shah and O’Shea, 2015) is also consistent with the idea that pATM must be physically recruited to viral DNA to mediate its inhibitory affect.

Although the MRN complex is well established as a host restriction factor for E4 mutant DNA replication (Evans and Hearing, 2003; 2005; Mathew and Bridge, 2007; 2008; Lakdawala et al., 2008), the role of the downstream ATM kinase in regulating viral replication is more controversial. Our results identify ATM as an important restriction factor for inhibiting E4 mutant DNA replication in HeLa cells, and SV40 transformed cells derived from a patient with Ataxia Telangiectasia (A-T) (Gautam and Bridge, 2013). Shah and O’Shea (2015) found that ATM inhibition substantially rescued DNA replication of an E1b55K/E4orf 3 double mutant in A549 cells. We also have found that the DNA replication defect of E4 mutants is rescued in A549 cells treated with an ATM inhibitor (Geehring and Bridge, unpublished data). In contrast, Lakdawala et al., (2008) reported that E4 mutant DNA replication was not substantially rescued in patient derived A-T cells that lack ATM. It is possible that the roles of MRN and ATM in interfering with E4 mutant DNA replication could vary in different cell lines. Different Ad serotypes have evolved different mechanisms of targeting the MRN complex and other DDR proteins (Pancholi and Weitzman, 2018). This could reflect differences in how MRN-dependent DDR activities affect Ad serotypes with different tissue tropisms.

We and others have proposed that recruitment of DDR proteins to E4 mutant genomes could inhibit viral DNA replication by masking the origin of replication (Mathew and Bridge, 2007; 2008; Karen and Hearing 2011). The MRN complex along with Mdc1, γH2AX, and pATM are among the early DDR proteins that localize to sites of DNA damage (Lisby et al., 2004). Mre11, Mdc1 and γH2AX are still efficiently recruited to E4 mutant VRCs in the absence of ATM (Fig. 2). This result is somewhat surprising since ATM is thought to be important for phosphorylating and amplifying the recruitment of γH2AX and Mdc1 to DSBs following IR (Bekker-Jensen and Mailand, 2010). Nevertheless, previous work has shown some redundancy during the DDR and other DDR kinases may be able to phosphorylate H2AX and recruit it and Mdc1 to DNA damage sites in the absence of ATM (Fernandez-Capetillo et al., 2004; Stiff et al., 2004). Mre11 and unphosphorylated ATM are still recruited to VRCs in the presence of the ATM kinase inhibitor KU60019 (Gautam and Bridge, 2013). Since E4 mutant DNA replication is rescued in cells lacking ATM, and in the presence of ATM kinase inhibitors (Gautam and Bridge, 2013), our data indicate that recruitment of these early DDR proteins is not sufficient to inhibit viral DNA replication.

Activated pATM could inhibit E4 mutant DNA replication by recruiting additional downstream DDR factors to VRCs. ATM-mediated phosphorylation of Mdc1 recruits RNF8 to DSBs, which in turn adds ubiquitin molecules to γH2AX to facilitate the recruitment of 53BP1 (Mailand et al., 2007). We found that RNF8 and 53BP1 are co-localized with pATM at VRCs during E4- infection (Fig. 3), consistent with the idea that pATM is important for localization of these proteins at DNA damage sites. Indeed, RNF8 and 53BP1 failed to localize with E4- VRCs in the absence of ATM (Fig. 4). Infection conditions that rescued E4 mutant DNA replication by preventing pATM activation or its localization at VRCs also resulted in decreased 53BP1 at VRCs. In dl1010 infected cells neither pATM (Fig. 1) nor 53BP1 (Fig. 5) were recruited to well-developed VRCs that form when E4 11kDa is expressed. Similarly, we also observed reduced 53BP1 localization to E4- VRCs following treatment of HeLa cells with the ATM kinase inhibitor KU60019 (Fig. 5A). Our data suggest that failure to recruit pATM to VRCs results in inefficient recruitment of 53BP1 to these sites. It is possible that ATM kinase-dependent recruitment of 53BP1 or other ATM-dependent DDR factors could interfere with viral DNA replication, and thereby prevent the normal development of VRCs.

The mechanism through which ATM interferes with E4- DNA replication is still unclear. Recent investigations have highlighted the importance of ATM in a multitude of chromatin changes that occur at DSBs including ubiquitination, acetylation and methylation of histones (reviewed in Price and D’Andrea, 2013). These changes promote local relaxation of the chromatin at DSBs thereby allowing DDR factors to access the broken DNA. Our data show that ATM is required for recruitment of RNF8 and 53BP1 to E4- VRCs (Fig. 4). RNF8 is a histone modifier that adds ubiquitin to histones. Ad genomes interact with cellular histones during infection (Komatsu and Nagata, 2012) and are organized in nucleosome like structures (Ross et al., 2011). It is possible that the E4- genome is subjected to chromatin modification during DDR induction that could make it a less favorable substrate for the viral DNA polymerase and subsequently inhibit DNA replication. This model is supported by the observation that RNF8 and 53BP1 are detected with pATM only at poorly developed E4- VRCs. When we interfere with activation or localization of pATM, this prevents RNF8 and 53BP1 localization to VRCs, and correlates with their robust development (Figs. 3–5).

MN analysis of the chromatin structure of viral DNA ends indicated that E4- and Ad5 displayed a similar profile of protected fragments (Fig. 6C). Viral DNA ends were not organized in the typical nucleosome ladder seen with β-actin DNA (Fig. 6B). While we did see some protected fragments that migrated at the positions expected for the nucleosome ladder, there were numerous additional protected fragments observed with viral DNA. Since our probe detected sequences present at the termini of Ad genomes this could indicate that termini are not tightly organized in nucleosomes resulting in a more complex MN digestion pattern. Komatsu and Nagata (2012) have shown that cellular histones associate with viral DNA. However, Shah and O’Shea (2015) have found that while histone 3 is bound to the ends of viral DNA, it is less abundant there than in cellular DNA. The reduced level of histone binding could reflect a less tightly organized configuration of nucleosomes in the terminal regions of viral DNA, potentially contributing to the relatively complex pattern of protected fragments we observed following MN digestion of viral DNA (Figs. 6 and 7).

Although we did not detect any dramatic differences in the profile of MN digested fragments in E4- and Ad5 infections, there was a striking difference in the amount of viral DNA that was more resistant to MN treatment and remained undigested (Fig. 6C arrowheads). Ad5 consistently demonstrated higher levels of undigested DNA running close to the position of viral DNA that was not treated with MN than E4-. When MN digested samples were analyzed at different time points, we found that E4- and Ad5 viral DNA was equally sensitive to MN digestion at 2hpi. At 6hpi more Ad5 DNA was protected from MN digestion than E4-, and this was also observed at 16hpi (Figs. 6 and 7). We first observe foci of the 72kDa viral DNA binding protein at about 6–7 hpi. While these focal replication centers grow rapidly in Ad5 infected cells they remain small in E4-infections (Gautam and Bridge, 2013). Treating infected cultures with ATM inhibitor increased the amount of E4- DNA detected in the samples as expected (Fig. 7), since ATM inhibition rescues E4- DNA replication (Gautam and Bridge, 2013). Interestingly, the proportion of E4- MN resistant viral DNA also increased with ATM inhibition (Fig. 7). It is possible that the development of robust VRCs in ATM inhibitor treated cells (Fig. 5) protects E4- DNA from MN digestion (Fig. 7).

We have not identified any specific differences in the chromatin organization of E4- and Ad5 termini that could account for the ATM-dependent DNA replication defect of E4-. However, our data do not rule out the possibility that ATM could recruit specific inhibitory factor(s) to viral chromatin. More specific assays to look for the presence of ATM-dependent histone modifications in E4- and Ad5 chromatin could further address possible differences in the chromatin configuration of viral DNA that are ATM-dependent. We have speculated that ATM dependent changes in viral chromatin organization could restrict the ability of viral replication proteins to interact with viral DNA and initiate synthesis. However, it is also possible that the recruitment of ATM to viral DNA could affect elongation, or the processivity of the viral DNA replication mechanism. Experiments to delineate these possibilities are in progress.

In conclusion, we have found that the presence of several early DDR proteins at VRCs is not sufficient to interfere with E4 mutant DNA replication. In contrast, localization of active pATM and ATM-dependent DDR proteins in VRCs, is correlated with poor development of these sites and reduced levels of E4 mutant DNA. Further investigations will be needed to determine if specific ATM dependent changes in viral chromatin or the viral DNA replication mechanism are responsible for reduced E4 mutant DNA levels following induction of the cellular DDR.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Arnold Levine and Tommy Linné for providing E2 72kDa antibodies used in this study. We thank undergraduate researcher Colleen Henry for her work on the project, and all the members of our laboratory for their suggestions and support. This research was supported by NIH National Cancer Institute (grant CA82111), and awards from Miami University.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Araujo FD et al. , 2005. Adenovirus type 5 E4orf3 protein targets the Mre11 complex to cytoplasmic aggresomes. J. Virol 79 (17) 11382–11391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker A et al. , 2007. Adenovirus E4 34 k and E1b 55 k oncoproteins target host DNA ligase IV for proteasomal degradation. J. Virol 81 (13), 7034–7040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB, 2003. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature 421 (6922), 499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekker-Jensen S, Mailand N, 2010. Assembly and function of DNA double-strand break repair foci in mammalian cells. DNA Repair (Amst). 9 (12), 1219–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackford AN, Jackson SP, 2017. ATM, ATR, and DNA-PK: The Trinity at the Heart of the DNA Damage Response. Mol. Cell 66 (6), 801–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge E, Ketner G, 1989. Redundant control of adenovirus late gene expression by early region 4. J. Virol 63 (2), 631–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burma S, et al. , 2001. ATM phosphorylates histone H2AX in response to DNA double-strand breaks. J. Biol. Chem 276 (45), 42462–42467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson CT, et al. , 2003. The Mre11 complex is required for ATM activation and the G2/M checkpoint. EMBO J. 22 (24) 6610–6620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson CT, et al. , 2009. Mislocalization of the MRN complex prevents ATR signaling during adenovirus infection. EMBO J. 28 (6), 652–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerosaletti K, Wright J, Concannon P, 2006. Active role for nibrin in the kinetics of Atm activation. Mol. Cell. Biol 26 (5), 1691–1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doil C, et al. , 2009. RNF168 binds and amplifies ubiquitin conjugates on damaged chromosomes to allow accumulation of repair proteins. Cell 136 (3), 435–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JD, Hearing P, 2003. Distinct roles of the adenovirus E4 ORF3 protein in viral DNA replication and inhibition of genome concatenation. J. Virol 77 (9), 5295–5304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JD, Hearing P, 2005. Relocalization of the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 complex by the adenovirus E4 ORF3 protein is required for viral replication. J. Virol 79 (10), 6207–6215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falck J, Coates J, Jackson SP, 2005. Conserved modes of recruitment of ATM, ATR and DNA-PKcs to sites of DNA damage. Nature 434 (7033), 605–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Capetillo O, et al. , 2004. H2AX: the histone guardian of the genome. DNA Repair (Amst.) 3 (8–9), 959–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester NA, et al. , 2011. Serotype-specific inactivation of the cellular DNA damage response during adenovirus infection. J. Virol 85 (5), 2201–2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam D, Bridge E, 2013. The kinase activity of ataxia-telangiectasia mutated interferes with adenovirus E4 mutant DNA replication. J. Virol 87 (15), 8687–8696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg M, et al. , 2003. MDC1 is required for the intra-S-phase DNA damage checkpoint. Nature 421 (6926), 952–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingworth R, Grand RJ, 2015. Modulation of DNA damage and repair pathways by human tumour viruses. Viruses 7 (5), 2542–2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huen MS, et al. , 2007. RNF8 transduces the DNA-damage signal via histone ubiquitylation and checkpoint protein assembly. Cell 131 (5), 901–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S, Stein A, 1994. Micrococcal nuclease digestion of nuclei reveals extended nucleosome ladders having anomalous DNA lengths for chromatin assembled on non-replicating plasmids in transfected cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 22 (3), 370–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karen KA, Hearing P, 2011. Adenovirus core protein VII protects the viral genome from a DNA damage response at early times after infection. J. Virol 85 (9), 4135–4142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu T, Nagata K, 2012. Replication-uncoupled histone deposition during adenovirus DNA replication. J. Virol 86 (12), 6701–6711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakdawala SS, et al. , 2008. Differential requirements of the C terminus of Nbs1 in suppressing adenovirus DNA replication and promoting concatemer formation. J. Virol 82 (17), 8362–8372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Paull TT, 2004. Direct activation of the ATM protein kinase by the Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 complex. Science 304 (5667) 93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisby M, et al. , 2004. Choreography of the DNA damage response: spatiotemporal relationships among checkpoint and repair proteins. Cell 118 (6), 699–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailand N, et al. , 2007. RNF8 ubiquitylates histones at DNA double-strand breaks and promotes assembly of repair proteins. Cell 131 (5), 887–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew SS, Bridge E, 2007. The cellular Mre11 protein interferes with adenovirus E4 mutant DNA replication. Virology 365 (2), 346–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew SS, Bridge E, 2008. Nbs1-dependent binding of Mre11 to adenovirus E4 mutant viral DNA is important for inhibiting DNA replication. Virology 374 (1), 11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pancholi NJ, Price AM, Weitzman MD, 2017. Take your PIKK: tumour viruses and DNA damage response pathways. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci 372 (1732) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pancholi NJ, Weitzman MD, 2018, Serotype-specific restriction of wild-type adenoviruses by the cellular Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 complex. Virology 518, 221–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipson L, 1961. Adenovirus assay by the fluorescent cell-counting procedure. Virology 15 (3), 263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash A, Jayaram S, Bridge E, 2012. Differential activation of cellular DNA damage responses by replication-defective and replication-competent adenovirus mutants. J. Virol 86 (24), 13324–13333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price BD, D’Andrea AD, 2013. Chromatin remodeling at DNA double-strand breaks. Cell 152 (6), 1344–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross PJ, 2011. Assembly of helper-dependent adenovirus DNA into chromatin promotes efficient gene expression. J. Virol 85 (8), 3950–3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fitsch EF, Maniatis T, 1989. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Ed., Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor. [Google Scholar]

- Shah GA, O’Shea CC, 2015. Viral and cellular genomes activate distinct DNA damage responses. Cell 162 (5), 987–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart GS, et al. , 2003. MDC1 is a mediator of the mammalian DNA damage checkpoint. Nature 421 (6926), 961–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart GS, et al. , 2009. The RIDDLE syndrome protein mediates a ubiquitin-dependent signaling cascade at sites of DNA damage. Cell 136 (3), 420–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiff T, et al. , 2004. ATM and DNAPK function redundantly to phosphorylate H2AX after exposure to ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 64 (7), 2390–2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracker TH, Carson CT, Weitzman MD, 2002. Adenovirus oncoproteins inactivate the Mre11- Rad50-NBS1 DNA repair complex. Nature 418 (6895), 348–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stucki M, et al. , 2005. Mdc1 directly binds phosphorylated histone H2AX to regulate cellular responses to DNA double-strand breaks. Cell 123 (7), 1213–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stucki M, Jackson SP, 2006. GammaH2AX and MDC1: anchoring the DNA-damage-response machinery to broken chromosomes. DNA Repair (Amst). 5 (5), 534–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiden MD, Ginsberg HS, 1994. Deletion of the E4 region of the genome produces adenovirus DNA concatemers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91 (1), 153–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg DH, Ketner G 1983. A cell line that supports the growth of a defective early region 4 deletion mutant of human adenovirus type 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80 (17), 5383–5386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You Z, et al. , 2005. ATM activation and its recruitment to damaged DNA require binding to the C terminus of Nbs1. Mol. Cell. Biol 25 (13), 5363–5379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]