Abstract

This paper discusses the need for research on the psychometric adequacy of self‐completed problem checklists to classify child and adolescent psychiatric disorder based on proxy assessments by parents and self‐assessments by adolescents. We put forward six theoretical arguments for expecting checklists to achieve comparable levels of reliability and validity with standardized diagnostic interviews for identifying child psychiatric disorder in epidemiological studies and clinical research. Empirically, the modest levels of test–retest reliability exhibited by standardized diagnostic interviews – 0.40 to 0.60 based on kappa – should be achievable by checklists when thresholds or cut‐points are applied to scale scores to identify a child with disorder. The few studies to conduct head‐to‐head comparisons of checklists and interviews in the 1990s concurred that no construct validity differences existed between checklist and interview classifications of disorder, even though the classifications of youth with psychiatric disorder only partially overlapped across instruments. Demonstrating that self‐completed problem checklists can classify disorder with similar reliability and validity as standardized diagnostic interviews would provide a simple, brief, flexible way to measuring psychiatric disorder as both a categorical or dimensional phenomenon as well as dramatically lowering the burden and cost of assessments in epidemiological studies and clinical research.

Keywords: checklists, child psychiatric disorder, interviews, reliability, validity

1. INTRODUCTION

Self‐completed problem checklists (i.e. questionnaires) and standardized diagnostic interviews are the two most common assessment instruments used to measure psychiatric disorder in children (Angold, 2002; Verhulst & Van der Ende, 2002). Interviews, developed to classify child disorders defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and International Classification of Diseases (ICD), are of two general types: (1) structured interviews which are scripts read by interviewers to respondents; they rely on the unaided judgement of respondents to report on the presence of symptoms, their duration and impact on functioning; and (2) semi‐structured interviews which direct interviewers to inquire about symptoms and rely on them to make informed judgements about the presence, duration and impact of symptoms, resolving discrepancies between informants (e.g. parent and youth).

Most self‐completed problem checklists include brief descriptions of symptoms of mental disorders rated on a frequency or severity continuum and then summed to compute a scale score. These scale scores are interpreted using a threshold or cut‐point to classify a child with disorder. Although most of these instruments have used factor analysis to identify items and dimensions for assessment, some like the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) Predictive Scales (Lucas et al., 2001) have created dimensions and selected items to reflect the categories and symptoms identified in the DSM; while others, such as the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) were initially created by factor analysis and have later drawn parallels between their items and dimensions, with DSM symptoms and disorders (Achenbach, Dumenci, & Rescorla, 2003).

There are a number of reasons to believe that standardized diagnostic interviews provide a better approach to classifying child disorder than checklists. Interviews were developed explicitly to operationalize DSM or ICD criteria, including symptoms and other prerequisites for classification; they also provide opportunities to: motivate participants, eliminate literacy problems, pursue complex lines of inquiry such as assessing disorder specific impairment and ensuring standardization of data collection – characteristics associated with high quality measurement. Unfortunately, most diagnostic interviews demand a lot of time from respondents and are expensive to implement. For example, the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Fourth Edition (DISC‐IV) takes on average 70 minutes to complete for a non‐clinic respondent (general population) and 90–120 minutes for a clinic respondent (Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab‐Stone, 2000). Training that can require 1–2 weeks and provisions for monitoring interviewers add substantially to assessment costs. Checklists, unlike interviews, are brief, simple, inexpensive to implement, pose little burden to respondents, can be administered in almost any setting to multiple informants (e.g. parents, teachers, and youth) using various modes of administration (e.g. in person, by mail, computer) and exhibit relatively little between‐subject variation in completion times (Myers & Winters, 2002).

The time burden to respondents and high cost of standardized diagnostic interviews raise concern about their viability for future use in epidemiological studies and clinical research. The pressure to limit interview time in general population studies is a function of cost, burden to participants and attempts to increase response which has been eroding for many years (Atrostic, Bates, Burt, & Silberstein, 2001). Even in routine clinical practice, there is resistance to using standardized diagnostic interviews (Angold & Costello, 2009), partly due to cost and time burden (Thienemann, 2004).

This paper argues for research that compares the reliability and validity of self‐completed checklists and standardized diagnostic interviews for classifying child psychiatric disorder. It is motivated by concerns about the respondent burden and high costs associated with the use of interviews, the practical advantages of checklists, arguments for expecting checklists to serve the objectives and requirements of classification as well as interviews and the absence of empirical evidence that interviews are more useful psychometrically than checklists for identifying child psychiatric disorder.

2. CHECKLISTS, INTERVIEWS AND CLASSIFICATION

Why should self‐completed problem checklists serve the objectives and requirements of classification as well as interviews? To begin, “structured” standardized interviews depend on respondents to identify symptoms and their characteristics without probing. The dependence on respondents in these interviews is similar to the dependence on respondents completing a checklist on their own except for the potential error introduced by interviewer characteristics and interviewer–respondent exchanges. Respondent–interviewer interaction is difficult to standardize and one of the most variable aspects of data collection (Martin, 2013). Arguably, this challenge of standardization is larger in “semi‐structured” interviews. Although directed probing is intended to enhance the quality of response, there is evidence that interviewer effects are associated positively with the rate at which they use follow‐up probes to obtain adequate responses (Mangione, Fowler, & Louis, 1992). Furthermore, there is evidence to indicate that self‐completed questionnaires versus structured interviews yield higher levels of disclosure when assessing sensitive information such as delinquency, suggesting that they may provide more valid information (Krohn, Waldo, & Chiricos, 1974).

Second, using brief descriptions, it is possible for checklists to cover the same symptom content as interviews. It may also be easier for respondents to process short behavioural descriptions seen on a page than to understand the meaning of extended, multi‐component questions read by an interviewer. Evidence exists that snap judgements based on brief observations or “thin slices” of behaviour can be intuitive, efficient and accurate and are undermined by excessive deliberation (Ambady, 2010). Furthermore, in their brevity, directness and single focus, checklist items mimic the qualities of good survey questions (Streiner & Norman, 2008).

Third, interview developers are concerned about participants using negative responses to shorten interview time (Kessler et al., 1998). In interviews, this has led to the use of screening questions that link participants with relevant modules before they can detect the advantages of negative responses. This response tendency in interviews exemplifies the perceived burden of participating in psychiatric interviews that could lead generally to the under‐identification of disorder. It also contributes to lost information about psychiatric symptoms. This is taken to the extreme in the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI‐KID: Sheehan et al., 2010). A negative response to a single question, “Has anyone – teacher, baby sitter, friend or parent – ever complained about his/her behaviour or performance in school?” directs interviewers to skip all questions associated with conduct, oppositional defiant and attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Fourth, DSM and ICD classifications of disorder require the presence of: (1) a predetermined number of symptoms, (2) significant impairment linked to those symptoms, and in some instances, (3) an age of onset and duration criteria. Interviews using conditional questions and skip patterns are well designed to assess compound criteria linked to individual disorders. However, assessing disorder this way may be counterproductive. The DSM has never explicitly defined impairment (Spitzer & Wakefield, 1999), leaving open its measurement to investigators. Also, it has been shown that combining multiple criteria can lead to increased error and reduce diagnostic accuracy (McGrath, 2009). By avoiding the use of compound criteria, checklists could have a slight reliability advantage over interviews. If impairment is deemed to be a criterion for disorder, checklists could measure it as a separate phenomenon, uncoupled from symptoms, as recommended by Rutter (2011).

Fifth, the emotional and behavioural symptoms used to define most of the common disorders of children and youth are quantitative traits that exist on a frequency or intensity continuum. Usually, they are given equal weight and summed to obtain a symptom score. While checklists ask respondents to rate the occurrence of problems on some underlying continuum (e.g. never, sometimes, often), interviews typically encourage respondents to decide if a symptom is present or absent. For example, the DISC allows a response of “sometimes” for questions on impairment but restricts symptom responses to “yes” or “no” (Fisher, Lucas, Lucas, Sarsfield, & Shaffer, 2006). The process of forcing respondents to make binary decisions about symptoms that exist along an underlying continuum could reduce reliability and validity, and decrease standardization across interviewers in the way they probe or the response expectancies they elicit in respondents.

If symptoms are quantitative traits given equal weight, is it logical to encourage binary responses when it may be more efficient, simpler cognitively and truer to the phenomenon to ask for graded responses (3+ options)? Graded compared to binary response options have the advantage of increasing the amount of construct variance associated with individual items, potentially reducing the number of items needed for achieving adequate reliability (Morey, 2003). Scales possessing more variance provide finer discriminations among individuals and more cut‐point or threshold options for classification. Although unproven, such scales may also result in higher levels of test–retest reliability when converted to binary classifications at any given threshold. This could occur if proportionately more respondents were located farther away from the threshold and less susceptible to drifting back and forth at random across the threshold depending on the timing or circumstances of assessment.

Sixth, child and adolescent disorders are judgements, formed by clinical consensus about patterns of observed emotional and behavioural problems in conjunction with normative judgements about their impact on functioning and perceived need for help. Debate about the true nature of psychopathology as categorical or dimensional is being replaced by the idea that both conceptualizations are appropriate (Coghill & Sonuga‐Barke, 2012) depending on the properties of disorder we wish to emphasize (Pickles & Angold, 2003) and the clinical circumstances and research questions we wish to address (Kraemer, Noda, & O'Hara, 2004). The categories of disorder created by diagnostic interviews serve many practical objectives associated with decision‐making by clinicians, administrators and policy developers, but does it make sense to create assessment instruments that restrict our conceptualization of disorder to one form of expression, especially if simple, brief measurement approaches which have many more uses can achieve the same classification objective with comparable psychometric adequacy?

The additional uses of checklists flow directly from the dimensional ratings that make up their individual scales. If using thresholds to identify child psychiatric disorder can produce classifications comparable in reliability and validity to structured interviews, then it would be possible to identify other thresholds (mild, moderate, severe) that would serve clinical needs to monitor progress. Extending this to the evaluation of clinical interventions or public health initiatives, dimensional measures of psychiatric disorder are the only viable option for assessing change. The binary classifications produced by structured interviews are too insensitive to change to be useful for evaluation purposes. Accordingly, it is notable that structured interviews close out two classic approaches to assessing the psychometric adequacy: internal‐consistency reliability which assesses the adequacy of sampled items for operationalizing a homogenous construct; and sensitivity to change which assesses the usefulness of measurement instruments for detecting true change when it occurs.

3. CHECKLISTS COMPARED TO INTERVIEWS: RELIABILITY AND VALIDITY OF CLASSIFICATIONS

To examine the reliability and validity of checklists compared to interviews for identifying child psychiatric disorder, we conducted an informal review. A search was conducted using PubMed and Google Scholar and focused on the terms “interview” and “checklist”. Terms for “interview” included: structural/structured/semi‐structured interview; clinical interview; diagnostic interview; psychiatric interview; and interviewer‐based assessment. Terms for “checklist” included: survey; questionnaire; scales; assessment; inventory; screen; self‐complete; and self‐report. Other keywords were: classification; comparison; concordance; external validator/validation; test–retest; reliability; validity, kappa; and agreement. The following interview names were also used (both as acronyms and full titles): K‐SADS; MINI‐KID; DICA; DISC; CAPA; CIDI; ADIS‐C/P; ISCA; CAS; and ChIPS. Digital “snowballing” techniques were used to retrieve related articles, and reference lists of relevant articles were also scanned.

The primary author reviewed the articles and selected those papers which either reported on the test–retest reliability of a standardized diagnostic interview or included a head‐to‐head comparison of the reliability or validity of checklist and interview classifications of three or more disorders from the following list: conduct disorder (CD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), separation anxiety disorder (SAD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and major depressive disorder (MDD). Only those studies with 30 or more participants were retained.

3.1. Reliability

Answers to questions may fluctuate from day‐to‐day for any number of reasons associated with respondents or the way instruments are administered. Reliability quantifies the extent to which variability in the answers of respondents is attributable to real differences between them versus random error (Shrout, 1998). When respondent answers or scores are used to identify the presence/absence of disorder, the typical approach to assessing reliability is to repeat the questions after a time interval long enough for respondents to forget their answers and short enough to prevent real change from occurring (test–retest reliability). In this circumstance, the kappa statistic – a chance corrected measure of agreement is often used to estimate test–retest reliability (Cohen, 1960). Kappa is calibrated from 0.0 (no agreement) to 1.0 (complete agreement) and is sensitive to the prevalence (base rates) of disorder: as prevalence approaches zero, so will kappa (Shrout, 1998).

In our search, we identified only one study which directly compared the test–retest reliability of an interview versus a checklist to classify child psychiatric disorder (Boyle et al., 1997). In that study, the revised version of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA‐R: Reich & Welner, 1988) was compared with the Ontario Child Health Study revised (OCHS‐R) scales (Boyle et al., 1993a). All six disorders were examined. Based on parent assessments of 210 6–16 year olds, kappa estimates of test–retest reliability over an average of 17 days for the DICA‐R went from 0.21 (CD) to 0.70 (MDD) with an average of 0.48. Kappa estimates for the OCHS‐R classifications over an average of 48 days went from 0.27 (MDD) to 0.61 (ODD) with an average of 0.42. The different retest intervals – 17 and 48 days – is an important study limitation.

We identified 17 studies which provided test–retest reliability estimates for interviews administered to parents only (mostly mothers), mothers and youth combined or youth only. Nine of the 17 studies involved clinic samples; two, in mixed clinic/community samples; and six in community samples. Six of the nine clinic samples had fewer than 100 participants. All six community samples had more than a 100 participants. (Checklists were excluded from this review because typically they are evaluated as dimensional measures of disorder which was out‐of‐scope for our review.)

Test–retest reliability estimates both within and between studies exhibit substantial variability (Table 1). For example, in the study by Egger et al. (2006), reliability goes from 0.39 (GAD) to 0.74 (ADHD). Across studies, reliability estimates for GAD go from −0.03 to 0.79. In general, average reliability estimates were higher in mothers or mothers and youth combined (0.57) than in youth alone (0.45); and in clinic or mixed clinic/community samples (0.58) than in community samples (0.48) (not shown). These results suggest that the reliability of interviews for identifying disorder is both sample and respondent dependent, sensitive to the type of disorder being assessed and subject to wide fluctuations. Shrout (1998, p. 308) assigned the following terms to kappa intervals: fair, 0.41–0.60; moderate 0.61–0.80; and substantial, 0.81–1.0. By this reckoning, interviews provide fair reliability at best.

Table 1.

Test–retest reliability (Kappa) of six child psychiatric disorders classified using five standardized diagnostic interviews administered to mothers and youth sampled from clinic‐referred and community populations

| ADHD | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument | Reference | Sample1 | M/F or total N 2 | Age in years3 | Res4 | Interval (days)5 | ADHD | ODD | CD | SAD | GAD | MDD | Ave7 |

| CAPA | Eggera | clin | 307 | 2–5 | P | 3–28 | .74 | .57 | .60 | .60 | .39 | .72 | .60 |

| Angoldb | clin | 77 | 10–16 | P | 1–11 | n/a | n/a | .55 | n/a | .79 | .90 | .75 | |

| K‐SADS‐PL | Chambersc | clin | 31/21 | 6–17 | Co | <3 | n/a | n/a | .63 | n/a | .24 | .54 | .47 |

| DISC | Hod | clin | 78 | 9–18 | P | 22 | .81 | .55 | n/a | n/a | .51 | .82 | .67 |

| Hod | clin | 78 | 9–18 | Y | 22 | .25 | .41 | n/a | n/a | .37 | .58 | .40 | |

| Bravoe | clin | 97/49 | 4–17 | P | 12 | .506 | .456 | .476 | .646 | .446 | .486 | .49 | |

| Bravoe | clin | 83 | 11–17 | Y | 12 | n/a | n/a | .62 | .18 | n/a | .15 | .32 | |

| Shafferf | clin | 84 | 9–17 | P | 6.6 | .79 | .54 | .43 | .58 | .65 | .66 | .61 | |

| Shafferf | clin | 82 | 9–17 | Y | 6.6 | .42 | .51 | .65 | .46 | n/a | .92 | .59 | |

| Schwab‐Stoneg | clin | 39 | 11–17 | P | 7–21 | .55 | .88 | .87 | n/a | n/a | .72 | .76 | |

| Schwab‐Stoneg | clin | 41 | 11–17 | Y | 7–21 | n/a | .16 | .55 | .72 | n/a | .77 | .55 | |

| Flisherh | comb | 71/34 | 15.0 (2.2) | P | 14 | .56 | .66 | n/a | n/a | .457 | .66 | .58 | |

| Jenseni | clin | 73/24 | 9–17 | P | 13 | .69 | .67 | .70 | n/a | .58 | .69 | .67 | |

| Jenseni | clin | 73/24 | 9–17 | Y | 13 | .59 | .46 | .86 | n/a | .39 | .38 | .54 | |

| Jenseni | comm | 129/149 | 9–17 | P | 21 | .57 | .65 | .66 | n/a | .40 | .00 | .46 | |

| Jenseni | comm | 129/149 | 9–17 | Y | 21 | .43 | .23 | .60 | n/a | .30 | .29 | .37 | |

| Bretonj | comm | 260 | 6–14 | P | 14 | .60 | .56 | n/a | .44 | .57 | .32 | .50 | |

| Bretonj | comm | 145 | 12–14 | Y | 14 | n/a | n/a | .49 | .59 | .53 | .55 | .54 | |

| Riberak | comm | 124 | 9–17 | Co | <14 | .53 | .56 | .82 | .46 | –.03 | .29 | .44 | |

| Schwab‐Stonel | comm | 130/117 | 9–18 | P | 1–15 | .606 | .686 | .566 | .456 | .606 | .556 | .57 | |

| Schwab‐Stonel | comm | 130/117 | 9–18 | Y | 1–15 | .106 | .186 | .646 | .276 | .286 | .376 | .31 | |

| DICA | Boylem | comm | 210 | 6–16 | P | 7–21 | .59 | .51 | .21 | .32 | .57 | .70 | .48 |

| Boylen | comm | 137 | 12–16 | Y | 7–21 | .24 | .28 | .92 | n/a | .54 | .45 | .49 | |

| Ezpeletao | clinic | 110 | 7–177 | P | 11 | .53 | n/a | .77 | .56 | .59 | .10 | .51 | |

| Ezpeletao | clinic | 110 | 7–177 | Y | 11 | .79 | n/a | .27 | .39 | .47 | .66 | .52 | |

| Ezpeletap | comm | 244 | 3–7 | P | 4–40 | .83 | .65 | n/a | .76 | .50 | .67 | .68 | |

| MINI‐KID | Sheehanq | comb | 83 | 6–17 | Co | 1–5 | .87 | .71 | .85 | .70 | .64 | .75 | .75 |

| Ave Parent/Co8 | .65 | .61 | .62 | .52 | .46 | .56 | .57 | ||||||

| Ave Youth9 | .34 | .32 | .67 | .44 | .40 | .50 | .45 | ||||||

Note: CAPA, Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment; K‐SADS‐PL, Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, Present and Lifetime; DISC, Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children; DICA, Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents; MINI‐KID, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder; CD, conduct disorder; SAD, separation anxiety disorder; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder; n/a, not assessed.

Sample: clin = clinic, comb = clinic and community, comm = community.

M/F = males/females or total N = total sample size.

Age in years = minimum/maximum or mean, standard deviation.

Res = Respondent, P = parent; Y = youth; Co = combined parent and youth.

Interval (days) = minimum‐maximum or mean.

Age groups 7–11 and 12–17 years combined and average kappa reported.

Ave = mean kappa value across disorders for parent/combined and for youth.

Ave Parent/Co = mean kappa value for disorders assessed by parents averaged across studies.

Ave Youth = mean kappa value for disorders assessed by youth averaged across studies.

Egger et al. (2006);

Angold and Costello (1995);

Chambers et al. (1985);

Ho et al. (2005);

Bravo et al. (2001);

Shaffer et al. (2000);

Schwab‐Stone et al. (1993);

Flisher, Sorsdahl, and Lund (2012)

Jensen et al. (1995)

Breton, Bergeron, Valla, Berthiaume, and St‐Georges (1998);

Ribera et al. (1996);

Schwab‐Stone et al. (1996);

Boyle et al. (1997);

Boyle et al. (1993b);

Ezpeleta, de la Osa, Domènech, Navarro, and Losilla (1997);

Ezpeleta, de la Osa, Granero, Domènech, and Reich (2011);

Sheehan et al. (2010).

3.2. Validity

Do the answers to questions provided by respondents produce meaningful and useful distinctions? The process used to address this question is called construct validity and it works from a set of fundamental principles grounded in the philosophy of science (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955). Briefly, to know the meaning of something is to set forth the laws that govern its occurrence. A nomological network is an interlocking system of laws which constitute a theory. To evaluate the meaning of a classification, the construct which it represents is placed within a nomological network. These placements are evaluated empirically by testing hypotheses about the declared linkages between the construct in question and other measured constructs which inhabit the network.

In assessing the meaningfulness and usefulness of instruments to classify disorder in child psychiatry, there is no strong, evidentiary‐based consensus that links a network of measured variables to specific child disorders (i.e. nomological network). Instead, we draw on the results of research studies linking individual child disorders to differences in age and gender, heritability, psychosocial risk factors, neuropsychological and biological features, and differences associated with long‐term course and response to treatment (Cantwell, 1996) to identify candidate variables that might be used to evaluate the construct validity of new or competing instruments.

In our search, we identified only four reports that attempted in the same study to make head‐to‐head construct validity comparisons between self‐administered problem checklists and diagnostic interviews administered by trained lay persons: these studies concurred that no construct validity differences existed between checklist and interview classifications of disorder, even though the classifications of youth with psychiatric disorder only partially overlapped across instruments. For example, the studies by Jensen (Jensen et al., 1996; Jensen & Watanabe, 1999) compared the strength of association between school dysfunction, need for mental health services, family risk and child psychosocial risk with classifications of disorder derived from the DISC versus CBCL and found few significant differences for parents or youth. Gould, Bird, and Jaramillo (1993) reported similar results for the DISC versus CBCL on the use of professional mental health services, teacher perceptions of need for mental health services, grade repetition and stress. Similar results were obtained for comparisons between the DICA and OCHS‐R scales on impaired social functioning, poor school performance and several other variables (Boyle et al., 1997). Although one might argue that problem checklists are able to classify child disorder as well as interviews, the evidence bearing on this is dated, sparse and too limited methodologically to convince anyone that checklists could replace interviews in epidemiological studies or clinical research.

4. CHALLENGES TO ADDRESS

If there are reasons to believe that checklists might serve classification objectives as well as interviews and no empirical evidence exists indicating that interviews are superior, what are some of the challenges to putting this question to the test? The first challenge is conventional wisdom. Substantial resources have gone into the development of interviews tailored to the DSM and ICD, and a belief has arisen that interviews provide the best possible way to operationalize diagnostic criteria. In fact, standardized diagnostic interviews have become the de facto gold standard for clinical research (Rettew, Lynch, Achenbach, Dumenci, & Ivanova, 2009).

The second challenge is confusion over the different objectives served by interviews and the scientific requirements for assessing their adequacy. We focus strictly on a measurement objective – classifying disorder. In clinical contexts, personal interviews serve the broader diagnostic objectives of describing and explaining patient problems and needs with the goal of formulating a treatment plan (Rutter & Taylor, 2008). This involves a complex exchange between clinicians and patients attempting to negotiate a successful course of action that takes into account the capabilities of patients, their families and the context of their difficulties. Although checklists might be used to inform diagnostic judgements, they were never meant to substitute for the clinical processes associated with diagnosis and treatment planning. This also applies to standardized diagnostic interviews. In the clinical context, the findings of such instruments provide directions for inquiry. The measurement objective in classifying disorder for epidemiological studies or clinical research is very specific – to maximize the reliability and validity of assessment data. This restricted objective is one of the reasons to believe that checklists might be capable of exhibiting the same levels of psychometric adequacy as interviews. It also renders the question of checklist versus interview for identifying disorder open to scientific scrutiny.

The third challenge is the burden, high cost and general difficulty of designing good measurement studies. Comparing the test–retest reliability of competing instruments requires two assessment waves which will double respondent burden and increase the difficulty of enlisting participants. Added to this, reliability estimates are sample dependent. If the same instruments are to be used in both clinical and general populations, then a comparative study of instruments should sample from both groups to maximize the generalizability of the findings. However, the low prevalence of child psychiatric disorder in the general population means that there will be less between‐subject variability in the risk for disorder, fewer individuals testing positive for disorder, and proportionately more random measurement error. This results in the need to implement more complex two‐stage studies in the general population (i.e. screen for risk of disorder in stage 1, stratify on the basis of risk and then, at stage 2 over sample higher risk children for intensive study) or simply to select larger samples from general populations than clinics to ensure adequate statistical power for testing between‐instrument differences. Finally, in making head‐to‐head reliability comparisons between instruments, there are several design requirements: the sample and time interval for re‐assessments must be the same; order effects, neutralized by randomly allocating the sequence in which instruments are administered; and contamination arising from respondents remembering their answers to questions on the different instruments minimized by inserting tasks and asking other questions between instrument administrations when they are done in the same session.

Several strategies exist to help alleviate the practical challenges associated with study implementation. One, families are more likely to participate in studies when convinced that the study findings will have a discernible impact on our understanding of child psychiatric disorder or resource allocations for children's mental health. Two, compensating families for their time is a reasonable and effective strategy for aiding enlistment. Three, sampling from both clinical and general populations should not be difficult for most researchers and epidemiologists working out of university settings. Developing a research culture among clinicians in child mental health settings and pursuing research partnerships with local school boards can provide an effective way of facilitating access to these important groups. Finally, carefully developed, standard interview protocols can provide assurance that the reliability comparisons are internally valid.

In the absence of criterion measures of disorders (Faraone & Tsuang, 1994), the fourth challenge is comparing the validity of instruments. Researchers must draw on epidemiological studies to identify putative risk factors and correlates of disorder to examine construct validity. The importance of these variables for public health objectives (identifying groups of children at elevated risk) does not guarantee their usefulness for measurement studies (identifying individual children at risk) because their predictive values for disorder in measurement studies may be too low. For example, child sex and age exhibit differential associations with specific types of disorder such as depression (e.g. elevated among adolescent girls); and ADHD (e.g. elevated among pre‐adolescent boys). However, the validity coefficients for these disorders in measurement studies (phi correlations) are likely to be <0.15, providing little effect size room for testing instrument differences. In addition, many risk factors are associated with disorder in general and are not specific to an individual disorder, a challenge exacerbated by excessive overlap or comorbidity observed between disorders. The problem of specificity – the lack of clear, separable distinctions between disorders defined by the DSM and the factors associated with them – was identified 30 years ago in seminal studies conducted by Werry and colleagues (Reeves, Werry, Elkind, & Zametkin, 1987; Werry, Elkind, & Reeves, 1987a; Werry, Reeves, & Elkind, 1987b).

Several strategies exist to help alleviate the challenges associated with establishing construct validity. One, great care must be taken in the selection of construct validity variables. This requires an extensive literature review to ensure that the most promising variables are included in the study with a distinction made between variables that might be useful for distinguishing between individual disorders versus disorder as a general phenomenon (Shanahan, Copeland, Costello, & Angold, 2008). Two, because of the uncertainty associated with the selection of construct validity variables, it is prudent to assess as many variables as possible within the bounds of respondent tolerance. This will provide additional flexibility for testing hypotheses. Three, in the face of excessive overlap or comorbidity among individual disorders, they can be grouped into larger domains such as internalizing and externalizing disorders. This will increase the prevalence and variability of the disorders measured and likely improve distinctiveness of the groupings for hypothesis testing (Mesman & Koot, 2000). Four, strategies that increase the reliable between‐subject differences of the validity variables can increase effect sizes for hypothesis testing. There are several ways to do this. First, one can improve the reliability of measurement by repeating the assessments at a second occasion and combining them. Second, one can use multiple indicator variables to create latent variable representations of validity constructs in the context of structural equation modelling. Third, one can sample respondents in a way that maximizes between‐subject differences. For example, a mixture sample comprised of children and youth selected from the general population and from those attending mental health clinics may be the best strategy for maximizing the variability associated with both the psychiatric disorders of interest and the construct validity variables used in the instrument comparisons. Fourth, rather than testing validity differences between instruments one construct validity variable at a time, one can use identical sets of construct validity variables to predict child disorders identified by different instruments. Comparing the associations between the predicted and observed classifications of disorder would provide an omnibus test of instrument differences in their construct validity. Using sets of validity variables will also increase observed effect sizes while serving the objective of parsimony (fewer tests and less risk of type I errors). Finally, in the measurement of selected construct validity variables, we must be mindful of methodological factors (method of assessment and source of information) that could distort instrument comparisons because of correlated errors. If it is not possible to avoid these errors by using independent observations and tests, it is important that they be distributed evenly between the instruments of interest.

5. DISCUSSION

Many important objectives are served by representing child psychiatric disorder categorically; these include setting priorities for individual treatment (clinical decision‐making); programme planning and development (administrative decision‐making); and resource allocation to address population needs (government decision‐making). At the same time, dimensional representations of disorder offer psychometric premiums. These premiums have been quantified as a 15% increase in reliability and a 37% increase in validity over categorical measures (Markon, Chmielewski, & Miller, 2011). This argues for measures of child psychiatric disorder which can serve the pragmatics of measurement and analysis (dimensional measures) and the needs of decision‐makers (categorical measures). The binary response options of diagnostic interviews and their use of screening questions to skip modules limits and may foreclose their use as dimensional measures. In assessing child disorder, being able to substitute self‐completed problem checklists for diagnostic interviews could significantly reduce the costs and burden of data collection, facilitate the scientific study of child disorder and respond to the needs of decision‐makers.

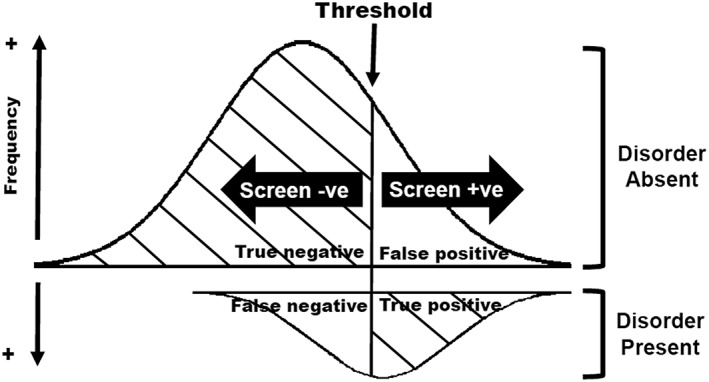

There is an urgent need for research studies that test hypotheses on the psychometric adequacy of checklists versus interviews in classifying child psychiatric disorder in general population and clinical samples. The modest and widely discrepant test–retest reliabilities associated with disorders classified by standardized diagnostic interviews shown in Table 1 is a key reason to undertake this research. In treating the standardized diagnostic interview as de facto criterion standard for classifying disorder, we overlook the fact that Figure 1 applies equally to interviews and checklists: children with and without disorder come from two hypothetical populations and our attempt to identify them are subject to classification errors (false positives and false negatives). Presumably, in both types of instruments, classification errors will be concentrated at the threshold used to identify risk. For any given threshold, random error associated with the person or measurement process will cause individuals to migrate back and forth across the boundary. This effect will be magnified for disorders that have low prevalence because random error will account for proportionately more of the between‐person variability in risk. In comparing the validity of checklists versus interviews for classifying disorder, the effects of instrument random error carry‐over to the validity tests and are compounded by measurement error embedded in the validity variables themselves. To ensure fair comparisons, the validity variables and models used to generate validity estimates must be identical for both instruments and, as much as possible, free of method variance that might give one type of instrument a biased advantage over the other.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical frequency distribution of interview symptoms or checklist scale scores attempting to classify childhood disorder

If test–retest reliability is similar for checklists and interviews, validity coefficients can also be similar even when these instruments identify different individuals with disorder. This raises the important methodological question of choosing checklist thresholds. Choosing a checklist threshold that matches the test positive rate (prevalence) of the interview will maximize the potential for between‐instrument agreement on the classification of disorder and equate the number of individuals testing positive and negative that are used in validity comparisons. Using a different criterion such as expected levels of disorder based on independent studies will lead to checklist identification rates that are higher or lower than the interview, depending on the specific disorder. This latter approach has the advantage of being independent of the interview: it makes no assumptions about the usefulness and meaningfulness of the interview for classifying disorder. The disadvantage is that estimates generated by independent studies will be higher or lower than those obtained by the interview, resulting in psychometric advantages (higher reliability) or disadvantages (lower reliability) to the checklist. Of course, head‐to‐head comparisons of the psychometric properties of competing standardized diagnostic interviews would be affected by prevalence in the same way.

In our view, the most serious impediments to comparing the psychometric adequacy of checklists versus interviews for classifying child psychiatric disorder are (1) the pervasive belief that reliable and valid classifications of child disorder can only be achieved by standardized diagnostic interviewers and (2) the tendency to conflate the clinical objectives of the diagnostic process with the practical measurement requirements of classification. Received wisdom is a formidable challenge to overcome. Agreeing on the difference between the clinical objectives served by the diagnostic process and the scientific requirements of classification should be an easier issue to address. If checklists can be substituted for interviews in epidemiological studies and clinical research, we will need to understand the psychometric implications associated with changing the number of items included as well as their content and placement. The flexibility of checklists makes them well suited for classification in a variety of circumstances such as community mental health agencies, as adjunctive measures in health surveys and even for monitoring child mental health trends over time in the general population.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All of the authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by research operating grant FRN111110 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Dr Boyle is supported by CIHR Canada Research Chair in the Social Determinants of Child Health; Dr Georgiades by a CIHR New Investigator Award and the David R. (Dan) Offord Chair in Child Studies; Dr Gonzalez by a CIHR New Investigator Award; Dr MacMillan by the Chedoke Health Chair in Child Psychiatry; and Dr Ferro by a Research Early Career Award from Hamilton Health Sciences.

Boyle MH, Duncan L, Georgiades K, et al. Classifying child and adolescent psychiatric disorder by problem checklists and standardized interviews. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1544 10.1002/mpr.1544

REFERENCES

- Achenbach, T. M. , Dumenci, L. , & Rescorla, L. A. (2003). DSM‐oriented and empirically based approaches to constructing scales from the same item pools. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 32, 328–340. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3203_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambady, N. (2010). The perils of pondering: Intuition and thin slice judgments. Psychological Inquiry, 21, 271–278. doi: 10.1080/1047840x.2010.524882 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angold, A. (2002). Chapter 3. Diagnostic interviews with parents and children In Rutter M., & Taylor E. (Eds.), Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (fourth ed.) (pp. 32–51). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Angold, A. , & Costello, E. J. (1995). A test–retest reliability study of child‐reported psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment. Psychological Medicine, 25, 755–762. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700034991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold, A. , & Costello, E. J. (2009). Nosology and measurement in child and adolescent psychiatry. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50, 9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01981.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atrostic, B. K. , Bates, N. , Burt, G. , & Silberstein, A. (2001). Nonresponse in US governmental household surveys: Consistent measures, recent trends, and new insights. Journal of Official Statistics, 12, 209–226. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, M. H. , Offord, D. R. , Racine, Y. A. , Fleming, J. E. , Szatmari, P. , & Sanford, M. N. (1993a). Evaluation of the revised Ontario Child Health Study Scales. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 34, 189–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb00979.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, M. H. , Offord, D. R. , Racine, Y. A. , Sanford, M. , Szatmari, P. , Fleming, J. E. , … Price‐Munn, N. (1993b). Evaluation of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents for use in general populations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 21, 663–681. doi: 10.1007/bf00916449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, M. H. , Offord, D. R. , Racine, Y. , Szatmari, P. , Sanford, M. , & Fleming, J. E. (1997). Adequacy of interviews versus checklists for classifying childhood psychiatric disorder based on parent reports. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54, 793–797. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830210029003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo, M. , Ribera, J. , Rubio‐Stipec, M. , Canino, G. , Shrout, P. , Ramirez, R. , … Taboas, A. (2001). Test–retest reliability of the Spanish version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC‐IV). Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29, 433–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton, J. J. , Bergeron, L. , Valla, J. P. , Berthiaume, C. , & St‐Georges, M. (1998). DISC 2.25 in Quebec: Reliability findings in light of the MECA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 37, 1167–1174. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199811000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell, D. P. (1996). Classification of child and adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 37, 3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01377.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, W. J. , Puig‐Antich, J. , Hirsch, M. , Paez, P. , Ambrosini, P. , Tabrizi, M. A. , … Davies, M. (1985). The assessment of affective disorders in children and adolescents by semistructured interview. Archives of General Psychiatry, 42, 696–702. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790300064008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 37–46. doi: 10.1177/001316446002000104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coghill, D. , & Sonuga‐Barke, E. J. S. (2012). Annual research review: Categories versus dimensions in the classification and conceptualisation of child and adolescent mental disorders – implications of recent empirical study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 469–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02511.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L. J. , & Meehl, P. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52, 281–302. doi: 10.1037/h0040957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger, H. L. , Erkanli, A. , Keeler, G. , Potts, E. , Walter, B. K. , & Angold, A. (2006). Test–retest reliability of the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA). Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 45, 538–549. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000205705.71194.b8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezpeleta, L. , de la Osa, N. , Domènech, J. M. , Navarro, J. B. , & Losilla, J. M. (1997). Fiabilidad test–retest del la adaptacion Espanola del la Diagnostic Interview for Child and Adolescents (DICA‐R). Psicothema, 9, 529–539. [Google Scholar]

- Ezpeleta, L. , de la Osa, N. , Granero, R. , Domènech, J. M. , & Reich, W. (2011). The Diagnostic Interview of Children and Adolescents for Parents of Preschool and Young Children: Psychometric properties in the general population. Psychiatry Research, 190, 137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone, S. V. , & Tsuang, M. T. (1994). Measuring diagnostic accuracy in the absence of a “gold standard”. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 650–657. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.5.650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, P. , Lucas, L. , Lucas, C. , Sarsfield, S. , & Shaffer, D. (2006). Columbia University DISC Development Group: Interviewer Manual. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/limited_access/interviewer_manual.pdf [12 June 2002].

- Flisher, A. J. , Sorsdahl, K. R. , & Lund, C. (2012). Test–retest reliability of the Xhosa version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children. Child: Care, Health and Development, 38, 261–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01195.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould, M. S. , Bird, H. , & Jaramillo, B. S. (1993). Correspondence between statistically derived behavior problem syndromes and child psychiatric diagnoses in a community sample. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 21, 287–313. doi: 10.1007/bf00917536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, T. , Leung, P. W. , Lee, C. , Tang, C. , Hung, S. , Kwong, S. , … Shaffer, D. (2005). Test–retest reliability of the Chinese version of the DISC‐IV. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 1135–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01435.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, P. S. , Watanabe, H. K. , Richters, J. E. , Roper, M. , Hibbs, E. D. , Salzberg, A. D. , … Liu, S. (1996). Scales, diagnosis and child psychopathology: II Comparing the CBCL and the DISC against external validators. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 24, 151–168. doi: 10.1007/bf01441482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, P. S. , & Watanabe, H. K. (1999). Sherlock Holmes and child psychopathology assessment approaches: The case of the false‐positive. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 38, 138–146. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199902000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, P. S. , Roper, M. , Fisher, P. , Piacentini, J. , Canino, G. , Richters, J. , … Schwab‐Stone, M. (1995). Test–retest reliability of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC 2.1). Archives of General Psychiatry, 52, 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C. , Wittchen, H.‐U. , Abelson, J. M. , Mcgonagle, K. , Schwarz, N. , Kendler, K. S. , … Zhao, S. (1998). Methodological studies of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) in the US National Comorbidity Survey. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 7, 33–55. doi: 10.1002/mpr.33 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer, H. C. , Noda, A. , & O'Hara, R. (2004). Categorical versus dimensional approaches to diagnosis: Methodological challenges. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 38, 17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(03)00097-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krohn, M. , Waldo, G. P. , & Chiricos, T. G. (1974). Self‐reported delinquency: A comparison of structured interviews and self‐administered checklists. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 65, 545–553. doi: 10.2307/1142528 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, C. P. , Zhang, H. , Fisher, P. W. , Shaffer, D. , Regier, D. A. , Narrow, W. E. , … Friman, P. (2001). The DISC Predictive Scales (DPS): Efficiently screening for diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 40, 443–449. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangione, T. W. , Fowler, F. J. , & Louis, T. A. (1992). Question characteristics and interviewer effects. Journal of Official Statistics, 8, 293–307. [Google Scholar]

- Markon, K. E. , Chmielewski, M. , & Miller, C. J. (2011). The reliability and validity of discrete and continuous measures of psychopathology: A quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 856–879. doi: 10.1037/a0023678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, E. (2013). Chapter 16. Surveys as social indicators: Problems in monitoring trends In Rossi P. H., Wright J. D., & Anderson A. B. (Eds.), Handbook of Survey Research (pp. 677–744). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, R. E. (2009). Predictor combination in binary decision‐making situations. Psychological Assessment, 20, 195–207. doi: 10.1037/a0023678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesman, J. , & Koot, H. M. (2000). Common and specific correlates of preadolescent internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 428–437. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.109.3.428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey, L. C. (2003). Chapter 15. Measuring personality and psychopathology In Weiner I. B. (Ed.), Handbook of Psychology. Volume 2. Research Methods in Psychology (pp. 377–406). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, K. , & Winters, N. C. (2002). Ten‐year review of rating scales. I: Overview of scale functioning, psychometric properties, and selection. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 41, 114–122. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200202000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickles, A. , & Angold, A. (2003). Natural categories or fundamental dimensions: On carving nature at the joints and the rearticulation of psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 15, 529–551. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, J. C. , Werry, J. S. , Elkind, G. S. , & Zametkin, A. (1987). Attention deficit, oppositional, and anxiety disorders in children: II Clinical characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 26, 144–155. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198703000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich, W. , & Welner, Z. (1988). Revised Version of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA‐R). St Louis, MO: Washington University School of Medicine.

- Rettew, D. C. , Lynch, A. D. , Achenbach, T. M. , Dumenci, L. , & Ivanova, M. Y. (2009). Meta‐analyses of agreement between diagnoses made from clinical evaluations and standardized diagnostic interviews. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 18, 169–184. doi: 10.1002/mpr.289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribera, J. C. , Canino, G. , Rubio‐Stipec, M. , Bravo, M. , Bauermeister, J. J. , Alegria, M. , … Guevara, L. (1996). The DISC 2.1 in Spanish: Reliability in a Hispanic population. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 37, 195–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01391.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, M. (2011). Child psychiatric diagnosis and classification: Concepts, findings, challenges and potential. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 647–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, M. , & Taylor, E. (2008). Chapter 4. Clinical assessment and diagnostic formulation In Rutter M., & Taylor E. (Eds.), Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (fourth ed.) (pp. 42–57). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab‐Stone, M. E. , Fisher, P. , Piacentini, J. , Shaffer, D. , Davies, M. , & Briggs, M. (1993). The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children‐Revised Version (DISC‐R), II: Test–retest reliability. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 32, 651–657. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199305000-00024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab‐Stone, M. E. , Shaffer, D. , Dulcan, M. K. , Jensen, P. , Fisher, P. , Bird, H. , … Rae, D. (1996). Criterion validity of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Version 2.3 (DISC‐2.3). Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 35, 878–888. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, D. , Fisher, P. , Lucas, C. P. , Dulcan, M. K. , & Schwab‐Stone, M. E. (2000). NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC‐IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 39, 28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, L. , Copeland, W. , Costello, E. J. , & Angold, A. (2008). Specificity of putative psychosocial risk factors for psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 49, 34–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01822.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, D. V. , Sheehan, K. H. , Shytle, R. G. , Janavs, J. , Bannon, Y. , Rogers, J. E. , … Wilkinson, B. (2010). Reliability and validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI‐KID). Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71, 313–326. doi: 10.4088/jcp.09m05305whi [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout, P. (1998). Measurement reliability and agreement in psychiatry. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 7, 301–317. doi: 10.1191/096228098672090967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R. L. , & Wakefield, J. C. (1999). DSM‐IV diagnostic criterion for clinical significance: Does it help solve the false positive problem? American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 1856–1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streiner, D. L. , & Norman, G. R. (2008). Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to their Development and Use (fourth ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thienemann, M. (2004). Introducing a structured interview into a clinical setting. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 43, 1057–1060. doi: http://www.axantum.com/axcrypt/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst, F. C. , & Van der Ende, J. (2002). Chapter 5. Rating scales In Rutter M., & Taylor E. (Eds.), Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (fourth ed.) (pp. 70–86). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Werry, J. S. , Elkind, G. S. , & Reeves, J. C. (1987a). Attention deficit, conduct, oppositional, and anxiety disorders in children: III Laboratory differences. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 15, 409–428. doi: 10.1007/bf00916458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werry, J. S. , Reeves, J. C. , & Elkind, G. S. (1987b). Attention deficit, conduct, oppositional, and anxiety disorders in children: I A review of research on differentiating characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 26, 133–143. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198703000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]