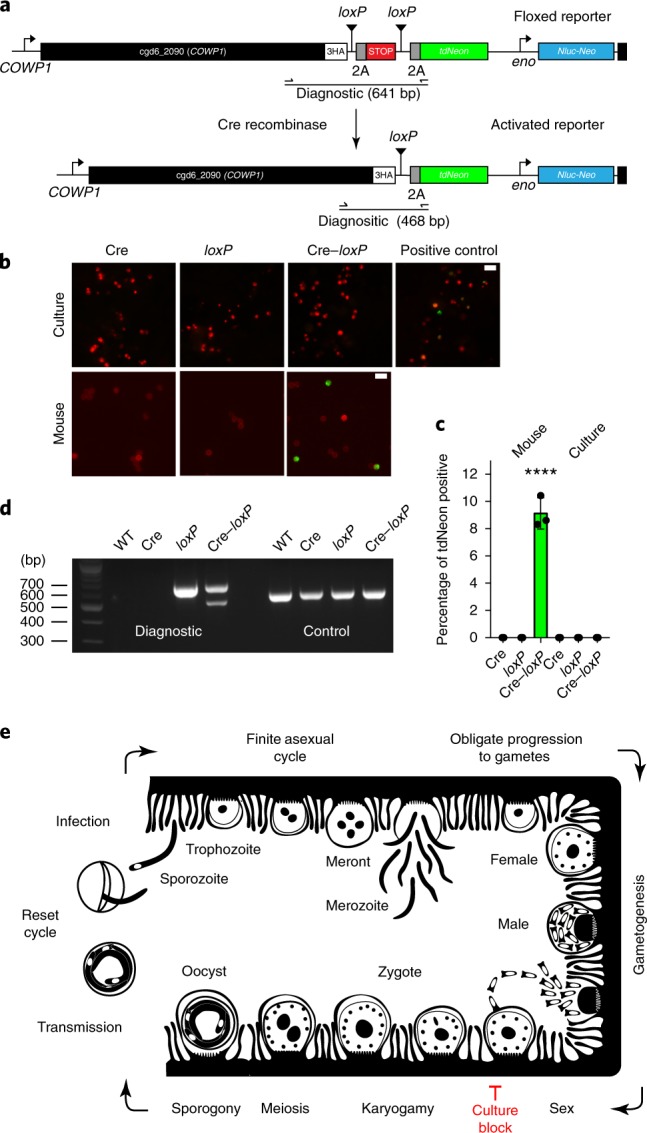

Fig. 6. A genetic fusion assay demonstrates fertilization in vivo but not in vitro.

a, To detect gamete fusion, we engineered two C. parvum strains, one that constitutively expresses Cre recombinase (Supplementary Fig. 11) and a second that carries a tdNeon reporter flanked by loxP at the COWP1 locus. b, Cre-mediated excision of a terminator results in reporter expression. HCT-8 cultures and Ifng−/− mice were infected with each strain individually or in combination. This experiment was performed twice. Cultured parasites were counterstained with anti-TrpB antibodies, oocysts with Macula pomifera agglutinin (both red) and scored for tdNeon expression. Scale bars, 10 µm. c, Three replicates were quantified for green fluorescence and 1,000 cells were counted for each replicate. Data are mean ± s.d. Green fluorescence was only observed after in vivo infection and only when both strains were present (****P = 0.0002, two-sided Student’s t-test). As a positive control, cells were infected with parasites that were crossed in vivo (indicated in b). d, PCR mapping of the floxed (diagnostic) and α-tubulin (control) loci using the primer pair shown in a. Genomic DNA was isolated from wild-type parasites as well as oocysts from the mouse infection experiments. Crossing resulted in a new amplicon that was consistent with precise Cre excision. This experiment was performed twice with similar results. e, Schematic model of the C. parvum life cycle that highlights the model of obligate progression to sex and the fertilization block in HCT-8 culture. We do not show type II meronts here, which are often depicted as an obligate step towards gametes. Although we observed meronts with four and eight nuclei, we did not find a quantitative link between the meronts with four nuclei and gametes (Supplementary Fig. 12).