Abstract

Pancreatic primary squamous cell carcinoma is rarer and no optimal treatment has been validated according to the tumor stage. The surgical resection was the only curative option. The radiotherapy or chemotherapy was performed for the other cases.

Keywords: chemotherapy, pancreatic cancer, radiotherapy, squamous cell carcinoma

Pancreatic primary squamous cell carcinoma is rarer and no optimal treatment has been validated according to the tumor stage. The surgical resection was the only curative option. The radiotherapy or chemotherapy was performed for the other cases.

1. INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer‐related death in most Western countries. Adenocarcinoma is the most common subtype. Primary squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is much rarer, with an incidence rate of 0.2%‐4%.1, 2 Squamous cells do not naturally exist in the pancreas. Squamous metaplasia of ductal columnar cells has been observed in chronic pancreatitis 3 and in 9%‐64% of cases examined at autopsy.4 Despite this high frequency, transformation to SCC is rare. Diagnosis of primary pancreatic SCC is made only after excluding other neoplastic lesions of the pancreas that contain squamous epithelial components, adenosquamous carcinoma, or metastatic disease.3 No optimal treatment has been validated. This study analyzed the management of pancreatic SCC in the literature. Additionally, we present a case of primary SCC in an elderly female with abnormal liver function tests and acute onset of painless jaundice.

1.1. Systematic literature review

We conducted a comprehensive, systematic search of the literature using the Medline and Cochrane Database, combined with a manual search from the years 1945 to 2017. The key words used were “Primary squamous cell carcinoma” OR “SCC” OR “Epidermoid carcinoma”, and “Pancreas.” The primary criteria were age, sex, symptoms, tumor location, tumor size, site of metastasis, tumor markers, imagery, treatment, and overall survival (OS). The advanced T stage of pancreatic cancer was defined according to the involvement of the vessels (superior mesenteric artery, portal vein, and celiac axis).

1.2. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism, version 6.01. Descriptive statistics were calculated. The Kaplan‐Meier method was used to calculate separate OS curves based on tumor resectability. A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

2. CASE REPORT

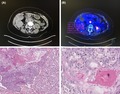

A 72‐year‐old woman with a medical history of arthrosis was admitted to our institution with jaundice. Laboratory testing indicated elevated transaminase levels (Alanine aminotransferase (ALT): 83 UI/L; aspartate aminotransferase (AST): 206 UI/L) and an elevated total bilirubin level (206 µmol/L). The carcinoembryonic antigen level was normal, and the cancer antigen 19‐9 level was slightly elevated (51 U/mL). The patient received an abdominal ultrasound and chest plus abdominal computed tomography (CT), which revealed a mass in the head of the pancreas measuring 2.2 × 1.7 cm with biliary and pancreatic ductal dilatation (Figure 1A). Positron emission tomography (PET)‐CT was used to investigate the origin of this mass, which revealed a unique pancreatic mass with a standardized uptake value of 12.5 (Figure 1B). Endoscopic ultrasound‐guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) was performed. The histopathology of the biopsy was consistent with SCC. The workup for identifying an alternative primary tumor was negative, including the gynecological, dermatological, “ear, nose, throat” examinations, and endoscopic evaluation of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tracts. A diagnosis of primary SCC of the pancreas was made. Based on the patient's age, performance status, and the nonmetastatic tumor stage, curative therapy was rapidly implemented. The pancreas tumor was treated by “en bloc” resection because it was adherent to transverse colon. We performed a cephalic duodenopancreatectomy (Whipple procedure) and transverse colectomy with manual anastomosis by laparotomy. The definitive histology confirmed the diagnosis of primary pancreatic SCC with perineural neoplastic invasion (Figure 1C–D). Based on the tumor‐node‐metastasis‐resection classification, the tumor was diagnosed as T2N0M0R0. Subsequent to surgery, the patient received chemotherapy using gemcitabine (six cycles). The patient is currently in complete remission after a follow‐up interval of 26 months. The nature and objectives of the study were explained to the patient, and informed consent was formally obtained. No reference to the patient's identity was made at any stage during data analysis or in the report.

Figure 1.

A, Abdominal CT scan showed a head pancreatic mass with greatest dimensions of 2.2 × 17 cm. B, PET scan showed hypermetabolic mass. C, Image of carcinoma with central necrosis and focal squamous differentiation (hematoxylin and eosin stain (H&E) ×200). D, H&E stained cell block shows a group of malignant squamous cells (×400)

3. DISCUSSION AND LITERATURE REVIEW

The literature search identified 44 eligible articles, written in English, French, German, or Spanish. A total of 52 cases of primary pancreatic SCC were included in the analysis (Table 1).1, 4, 9, 10, 11, 21, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53 The median age at diagnosis was 63.5 (range: 33‐81) years, and the majority (58.8%) of patients were male. A comparison of the clinicopathologic characteristics (n = 40) indicated that 31(75%) patients experienced abdominal pain, 19 (47.5%) anorexia or weight loss, and 11 (27.5%) jaundice. Of the reported cases with sufficient information (n = 45), tumor location was variable: head (48.9%), body (17.8%), tail (20%), and corporeo‐caudal (17.8%). In approximately half of the cases, a large pancreatic tumor (median size: 6.2 [range: 3‐10] cm) was diagnosed at the metastatic stage. The most common metastatic sites were the liver and lymph nodes. Of 36 patients with available information, abdominal CT, abdominal ultrasound, and PET were performed in 94.7%, 38.9%, and 16.7% of patients, respectively. The histological diagnosis was confirmed for 42 (82.4%) patients.

Table 1.

Clinical and radiological features of patients

| Reference | Year | Sex | Symptoms | Tumor location | Size (cm) | Extra pancreatic sites | Tumor markers | Imagery | Diagnosis method | Therapy |

Survival (Mo) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 57 | F | Epigastric pain | Body and tail | 5 × 6 | LN | CA 19‐9 (ND) | CT scan | Biopsy | Neoadjuvant radio‐chemo and surgery | 10 |

| 4 | 72 | M | Painless jaundice | Head | 6 | Invasion of the mesenteric vessels | NR |

AUS ERCP CT Scan EUS |

FNA | Palliative Roux en Y hepato‐jejunostomy and gastro‐enterostomy. | 4 |

| 42 | 77 | M | NR | Head | 6.5 | Lymph node | NR | NR | Surgery | Surgery | 26 (A) |

| 5 | 61 | M | Fatigue, weight loss, jaundice, pain, dark urine, and light‐colored stool | Head | 6.5 × 5.9 | Liver | ACE (ND)CA 19‐9 (ND) | CT Scan | NR | Palliative care | 2 |

| 6 | 68 | F | Abdominal pain | Head | 3 × 4 | Invasion of the superior mesenteric | CA 19‐9 (ND) |

CT scan EUS |

FNA | Palliative Radio | 3 |

| 7 | 62 | M | Tarry stool, fever, and general fatigue | Body, Tail | 8 | Expanding to the spleen and the left transverse colon with suspected invasion in the stomach |

CA 19‐9 (ND) ACE (ND) |

EG CT scan |

Surgery | 1) Pancreatectomy, total gastrectomy, splenectomy, and partial colectomy | 16 (A) |

| 8 | 70 | M | Weight loss, pruritus, and icterus | Head | 5.5 | LN | NR |

AUS CT scan ERCP |

Surgery |

1) Pancreaticoduodenectomy 2) Recurrence at 2 mo: Cisplatine 3) Docetaxel |

17 |

| 9 | 76 | M | Weight loss, painless jaundice, and abdominal pain | Head | 5.8 | Lymph node | NR |

CT scan PET scan ERCP |

FNA | Radio + 5 FU | 18 |

| 10 | 56 | M | Pain | Tail | 13 | None | NR | NR | Surgery |

1) Surgery 2) Recurrence at 3 mo: chemo |

3 (A) |

| 11 | 79 | M | Asymptomatic | Tail | 5 | LN, Liver | NR |

CT scan MRI PET‐CT |

Biopsy |

1) Tegafur/Gimeracil/Oteracil (S‐1) 2) Gemcitabine |

7 |

| 12 | 61 | M | Anorexia, epigastric pain | Head | NR | Liver |

CEA (ND) CA 19‐9 (ND) |

CT Scan EUS PET‐CT |

NR |

1) Gemcitabine + cisplatin +5FU 2) Leucoverin |

9.9 |

| 14 | 66 | F | Epigastric pain | Body | 4 × 3 | Superior mesenteric and celiac arteries |

CA 19‐9 (ND) ACE (ND) |

ASU CT scan |

FNA |

1) Gemcitabine + Oxaliplatine 2) Gemcitabine only |

9 |

| 14 | 79 | F | Upper abdominal pain and vomiting | Uncinate process | 5 × 8 | Invasion of the retroperitoneum | NC | CT scan | Autopsy | None | 1.5 |

| 15 | 70 | M | NR | NR | NR | Liver | NR | NR | NR | 5 FU + Cisplatine | 15 |

| 16 | 55 | M | NR | Head | 5 | NR | NR | NR | Surgery | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 10 |

| 17 | 63 | F | Anorexia | Body | 3 × 2 | Invasion of the celiac axis, the supraclavicular node, liver, cervical vertabra | CA 19‐9:209 UI/ml | CT scan | Node Biopsy FNA |

1) 5 FU + Cisplatine 2) Gemcitabine + Vinotelbine (2nd lign) + Radio |

12 |

| 18 | 48 | F | Anorexia, pain, jaundice | Head and uncinate process | 4.4 × 4.2 | Liver, spleen | NR |

ASU CT scan |

Liver Biopsy | Gastrojejunostomy, choledochojejunostomy, open cholecystectomy and then, Gemcitabine + Carboplatine | 4 |

| 19 | 67 | F | Anorexia, back pain | Tail | 6 × 6 × 7 | LN |

ACE (ND) CA 19‐9 (ND) |

CT scan | Surgery |

1) Total gastrectomy, distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy 2) Recurrence at 4 mo: Radio |

11 |

| 20 | 69 | F | Abdominal pain, jaundice | Head | 5 × 5 × 6 |

LN Locoregional invasion |

NR |

CT scan MRI ERCP |

Surgery | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 3 |

| 20 | 49 | M | NR | Tail | 7.5 | Peritoneal, lombo‐aortique, mediastinal adenopathy, Liver | NR | NR | Liver Biopsy |

1) Radio + 5 FU + Cisplatine 2) Gemcitabine |

8 |

| 20 | 68 | M | Abdominal pain, weight loss | Body | NR | None | NR | CT scan | FNA | Surgery | 3 |

| 20 | 63 | M | Abdominal pain, weight loss | NR | NR | Lung | NR | CT scan | FNA | Cisplatine + 5 FU and Radio | 1 |

| 20 | 80 | M | Abdominal pain, weight loss | NR | NR | Lung Liver Bone | NR | CT scan | FNA | Cisplatine + 5 FU and Radio | 1.5 |

| 20 | 79 | M | Abdominal pain, weight loss | NR | NR | None | NR | CT scan | FNA | Radio | 3.5 |

| 21 | 63 | M | Abdominal pain, weight loss | NR | NR | Lung Liver Bone | NR | CT scan | FNA | Cisplatine + Vinblastine | 7 |

| 21 | 38 | M | Abdominal pain, weight loss | NR | NR | Lung Liver | NR | CT scan | FNA | Radio | 1 |

| 22 | 69 | F | Epigastric pain | Body | 5 | Superior mesenteric artery | NR |

CT scan ERCP |

Biopsy | Radio | 7 (A) |

| 22 | 48 | M | Epigastric pain | Head | 4 × 6 | Superior mesenteric artery | CA19‐9:980 U/mL |

AUS CT scan |

CT‐ guided biopsy |

1) 5‐FU + Cisplatine 2) Palliative radio |

9 |

| 23, 38 | 42 | M | Vomiting, periumbilical pain. | Body and tail | 4 × 3.7 × 3.1 | Splenic vessels | CA 19‐9 (–) |

AUS CT scan |

Surgery | Spleno‐corporeo‐caudal pancreatectomy and FUFOL | 26 (A) |

| 24 | 73 | M | Abdominal pain, anorexia | Tail | 6 × 5.7 × 5.5 | NR | CA 19‐9:464 µ/mL |

CT scan PET scan |

FNA biopsy | Palliative care | 2 |

| 25 | 58 | F | NR | Body and tail | 8 | Infiltration of the gastric wall and mucosal ulceration, invasion of the spleen, the left renal capsule, the left adrenal gland. | NR | CT scan | Surgical biopsy | Surgery and Cisplatine + 5 FU | 3 (A) |

| 26 | 68 | F | Abdominal pain, weight loss | Body | 7 | None | NR | CT scan | Surgery | Surgery | 8 (A) |

| 27 | 57 | M | Hypercalcemia | Body and tail | NR | Periaortic, Peripancreatic, mediastinal LN, Liver, kidneys, adrenal gland metastasis | NR | NR | Autopsy | None | 3 |

| 28 | 63 | M | NR | Head | 3.5 | Liver | NR | NR | NR | Gemcitabine + 5 FU + Leucoverine | 6 |

| 29 | 52 | M | Melena, icteric, a large painful liver | NR | NR | Stomach, Liver | NR | AUS | Autopsy | None | 0.4 |

| 30 | 69 | F | NR | Head | 4 | NR | NR | NR | Intraoperative needle aspiration | Palliative care | 4 |

| 31 | 26 | F |

Rapidly worsening, jaundice |

Head | 3.5 | LN, muscle, bone | NR | CT scan | Surgery | Surgery and Gemcitabine + Oxaliplatine | 8 (A) |

| 32 | 57 | F | NR | Tail | 10.5 | None | NR | NR | Surgery | Surgery | 6 |

| 33 | 76 | M | NR | Body and tail | 9 | LN, metastasis | NR | NR | NR | None | 1 |

| 34 | 70 | F | NR | Head | 6 | Porta hepatis | NR | NR | NR | Radio | 3 |

| 35 | 50 | M | NR | Tail + Head | 8 | Liver | NR | NR | NR | Gemcitabine, FU and Goserelin | 5 |

| 36 | 33 | F | NR | Head | 13 | Lymph node | NR | NR | NR | Unconventional Immunotherapeutic regimen | 9 (A) |

| 37 | 76 | M | Painless jaundice. | Head | 5 | None | NR | CT scan | EUS biopsy |

Chemo (5FU) + radio then surgery |

10 (A) |

Abbreviations: (A), Alive; ASU, abdominal sonography ultrasound; Chemo, chemotherapy; CT, computerized tomography; EG, Esophago‐gastroscopy; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangio‐pancreatography; EUS, endoscopy sonography ultrasound; F, female; FNA, fine needle aspiration; FU, fluorouracil; FUFOL, 5‐fluorouracil; folinic acid; LN, lymph node M, male; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; ND, not detected; NR, not reported; Radio, radiotherapy; PET, positron emission tomography‐computed tomography.

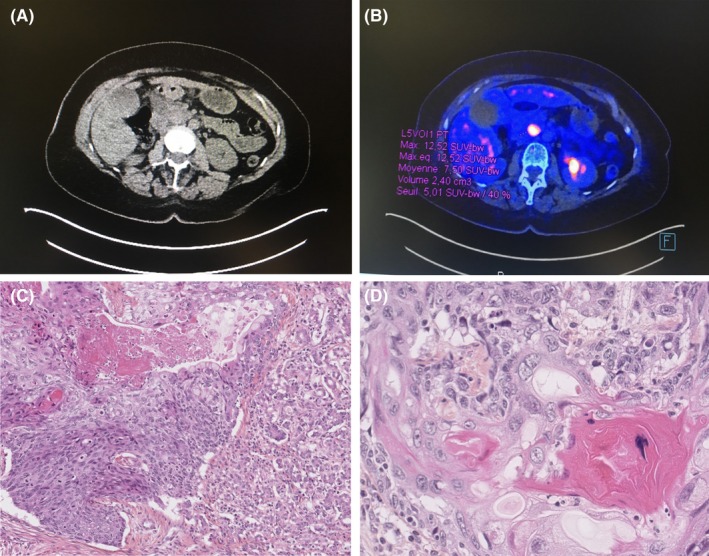

A total of 15 of 50 (30%) SCC cases were resectable. Of these 15 patients, 2 (13.3%) received neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and 3 (20%) received adjuvant chemotherapy (Figure 2). Three (20%) cases of local recurrence or metastasis were observed in this group after curative treatment (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the management of patients (n = number of patients, (%) percentage)

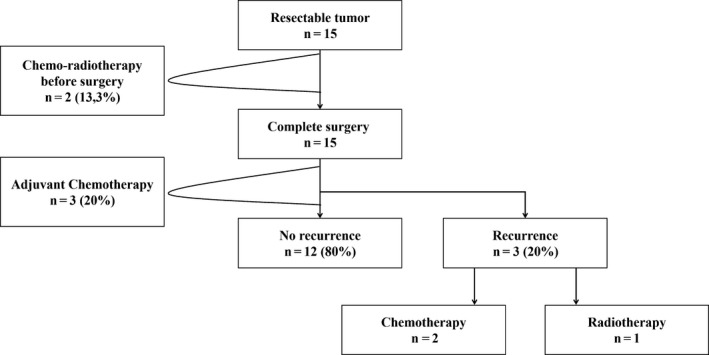

A total of 11 patients had a locally advanced tumor, and 10 (90%) of these patients received chemo‐ or radiotherapy (Table 2). The 24 (38.5%) patients with metastasis received palliative care (Table 2). The majority of patients with inoperable SCC received gemcitabine and cisplatin, either alone or in combination, as a first‐line treatment (Table 1).1, 4, 9, 10, 11, 21, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53 A total of eight cases in the metastasis group were excluded from the survival analysis because of insufficient information. The median OS was 17 months in the resectable group, compared with 8 months in the locally advanced tumor group and 4 months in the metastasis group (P = .0008; Figure 3).

Table 2.

Management of patients with locally advanced tumor or metastasis

| Palliative surgery | Chemotherapy | Radiotherapy | Chemo‐radiotherapy | Palliative care | Not reported | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locally advanced tumorn = 11 | 1 (9%) | 3 (27.3%) | 5 (45.5%) | 2 (18.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Metastatic SCC n = 26 |

1 (3.8%) | 6 (23.1%) | 1 (3.8%) | 6 (23.1%) | 10 (38.5%) | 2 (7.7%) |

Abbreviation: n, number of patients.

Figure 3.

Kaplan‐Meier survival estimates regarding overall survival (OS), by resectability status

Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas is exceedingly rare, with an incidence rate of 0.5%‐5%.39 Because of this rarity, it is often presumed to be a result of metastasis from another primary site.40 The pathogenesis is not well understood, and a number of mechanisms underlying its development have been proposed: malignant transformation of squamous metaplasia of ductal cells, squamous metaplasia in adenocarcinoma, and squamous differentiation with malignant transformation of pluripotent primitive cells.41 The first case of SCC was described by Lowry in 1949.42 Since then, only case reports from the literature have been available to guide workup and treatment. This review is the first study to examine the management of SCC and to describe the neoadjuvant, adjuvant, and palliative chemoradiotherapy used to treat it. Identification of the initial stage is necessary for the management of pancreatic cancer. Patients who may be eligible for potentially curative surgery must be identified accurately. Patients with locally advanced disease or metastasis must also be identified and treated with chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

3.1. Clinical symptoms

The literature review confirmed that the clinical presentation of SCC was similar to that of adenocarcinoma,5 with anorexia and epigastric pain as the main symptoms. The presenting symptom was often obstructive jaundice with involvement of the pancreatic head. The tumor location was the pancreatic head in 53% of cases and the body or tail in 20% of cases. A recent epidemiologic study, which identified 214 cases during 2000‐2012 using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, reported tumor locations of the pancreatic head in 47.7% of cases and the body or tail in 27.1% of cases.2

3.2. Examinations

In many of the cases included in this review, diagnosis of primary SCC of the pancreas was confirmed after eliminating other possibilities, in addition to immunohistological confirmation prior to treatment. In our case, the patient received an otorhinolaryngological assessment, endoscopic examination of the gastrointestinal tract, and gynecological examination, which were all normal. Additional biopsies may be needed to confirm that the malignant cells are not of adenosquamous origin.6 Minimally invasive methods, such as FNA, are replacing traditional surgical approaches to obtaining pancreatic tissue.7 FNA was the method used in this case report. Abdominal CT is often the first imaging test performed when a patient's symptoms suggest a pancreatic tumor.43 Other procedures and imaging tests used to aid diagnosis and identify metastasis include PET and pancreatic MRI.

3.3. Histological analysis

Histological examination of the pancreatic lesion confirmed the diagnosis of SCC.

3.4. Management of resectable tumors

It is necessary to identify the pancreatic tumor stage (resectable, locally advanced, or metastatic tumor) prior to initiating treatment. Surgery is the only effective therapy for pancreatic SCC. The quality of surgery is considered a key factor in the long‐term survival of patients with pancreatic cancer. In our case, the patient had a small, localized pancreatic tumor and received a cephalic duodenopancreatectomy with transverse colectomy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy. The resectability rate of SCC in this review was 29.4%, similar to the rates reported by Makarova‐Rusher et al: 10.4% for patients with SCC and 14.2% for patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma.2 Although significant progress has been made in the field of pancreatic resection recently, only 15%‐25% of patients present with resectable disease at the time of the primary diagnosis.44 This finding emphasizes the need for early diagnosis of, and therapeutic approaches to, pancreatic cancer.

No studies have evaluated the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy in pancreas SCC. All patients with resectable pancreatic tumors received curative surgery, subsequent to neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy if the patient's general condition permitted (13.3%). Neoadjuvant or exclusive chemoradiotherapy is critical in the management of rectal, anal, and esophageal SCC.45, 46, 47 The pancreas is a deep organ located near large vessels, and any progression of the tumor can render surgery impossible. Similar to adenocarcinoma of the pancreas, neoadjuvant treatment may be deemed unnecessary by radiochemotherapy or chemotherapy if the pancreatic SCC is resectable.48

Only 20% of patients received chemotherapy after curative surgery. For pancreatic adenocarcinoma, there is now irrefutable evidence that adjuvant chemotherapy improves both overall and disease‐free survival and that gemcitabine is the gold standard adjuvant drug.49 For other squamous cell cancers, such as of the esophagus, adjuvant chemotherapy is not systematically recommended but may be indicated based on poor prognostic factors such as incomplete resection.50

3.5. Management of locally advanced tumors

The majority of patients with locally advanced tumors received radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy exclusively. This treatment has been validated for other tumor locations, including anal, rectal, and esophageal SCCs.51 In pancreatic adenocarcinoma, neoadjuvant treatment is indicated only for patients initially staged as locally advanced/unresectable, enabling one‐third of patients to receive curative surgery.51 Since the approval of gemcitabine in 1997, more effective cytotoxic substances, such as nab‐paclitaxel, and combination regimens, such as FOLFIRINOX, have become available for locally advanced tumors, possibly leading to more effective adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatment concepts for potentially resectable tumors.8 Gemcitabine and cisplatin were the two principle drugs utilized.

3.6. Metastatic tumors

In this review, the majority (51%) of patients with SCC had stage IV disease on initial presentation, similar to the rate of 56.4% reported by Makarova‐Rusher et al.2 The primary metastatic seeding sites were the liver and lung. The majority of metastatic patients received palliative care, which was also the preferred treatment for patients in generally poor health. The other patients were treated with a combination of cisplatin and 5‐fluorouracil or gemcitabine and, less frequently, with radiochemotherapy. This approach is consistent with the recommendations for patients with pancreatic metastatic adenocarcinoma.

3.7. Survival

Even with therapy, SCC of the pancreas is associated with a high mortality rate and overall poor prognosis.52 Resectable cases had significantly better OS than that of nonresectable cases (17 months vs 7 months [locally advanced tumors] and 3 months [metastatic tumors]). Klain et al reported that prognosis remained poor whether the disease was resectable (median survival of 15 months) or unresectable (median survival of 3 months).53 Makarova‐Rusher et al reported a median OS of 9 months for the patients who underwent surgery compared with 3 months for those who received palliative treatment.2

This review has several limitations. The analysis was based on retrospective registers, and only case reports and case series were retrieved. Misclassification as primary pancreatic carcinoma is possible in the case of metastatic disease from another site. Consequently, there are few estimates of the degree of misdiagnosis. Despite these limitations, this review is the first study to evaluate the management of pancreatic SCC. This review reflects a global perspective, utilizing data from many countries, and can be used by medical personnel for treatment of a new case of pancreatic SCC.

4. CONCLUSION

Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas is aggressive and rare. Clinical presentation and diagnostic approaches are similar to those for other pancreatic tumors. Surgical resection is the only curative option but is often limited by local and distant metastases. A multidisciplinary approach is needed to improve long‐term survival in this still‐challenging disease. Prospective international research is required to validate the management of SCC.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

AT: involved in conception of paper, writing, and critical appraisal. JJ: involved in writing and critical appraisal. SDF: involved in writing and critical appraisal. AC: involved in conception of paper, writing. SBM: involved in writing and critical appraisal. NC: involved in critical appraisal. FF: involved in critical appraisal DV: treated the patients MM: involved in critical appraisal, expert opinion, and current oncology evidence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

Taibi A, Jacques J, Durand Fontanier S, et al. Long‐term survival after surgery of pancreatic primary squamous cell carcinoma: A case report and literature review. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7:2092–2101. 10.1002/ccr3.2429

REFERENCES

- 1. Schultheis AM, Nguyen GP, Ortmann M, et al. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Pancreas in a Patient with Germline BRCA2 Mutation‐Response to Neoadjuvant Radiochemotherapy. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2014;2014:860532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Makarova‐Rusher OV, Ulahannan S, Greten TF, Duffy A. Pancreatic squamous cell carcinoma: a population‐based study of epidemiology. Clinicopathologic Characteristics and Outcomes. Pancreas. 2016;45(10):1432‐1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Layfield LJ, Cramer H, Madden J, Gopez EV, Liu K. Atypical squamous epithelium in cytologic specimens from the pancreas: cytological differential diagnosis and clinical implications. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001;25(1):38‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anagnostopoulos GK, Aithal GP, Ragunath K, Kaye P, Rowlands BJ. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas: report of a case and review of the literature. JOP. 2006;7(1):47‐50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Minami T, Fukui K, Morita Y, et al. A case of squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas with an initial symptom of tarry stool. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16(9):1077‐1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lin E, Veeramachaneni H, Addissie B, Arora A.Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas. Am J Med Sci. 2018;355(1):94‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zacharia G, Levine J, Winstead NS, Antillon MR, Davis NK. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound‐guided fine needle aspiration. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2012;21(3):321‐323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sinn M, Bahra M, Denecke T, Travis S, Pelzer U, Riess H. Perioperative treatment options in resectable pancreatic cancer ‐ how to improve long‐term survival. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology. 2016;8(3):248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kashani A, Kahn M, Jamil LH. Diagnosis of primary squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas using endoscopic ultrasound‐guided core needle biopsy. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2015;5(1):72‐74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ikeda A, Okuno T, Miki I, Yokozaki H, Kutsumi H, Azuma T. A case report: pancreatic squamous cell carcinoma with effective response by S‐1 therapy. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2014;7(1):79‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. De Souza AL, Saif MW. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas. JOP. 2014;15(6):630‐631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nikfam S, Sotoudehmanesh R, Pourshams A, Sadeghipour A, Sotoudeh M, Mohamadnejad M. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas. Arch Iran Med. 2013;16(6):369‐370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nakashima H, Hayakawa T, Hoshino M, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas with massive invasion of the retroperitoneum. Intern Med. 1995;34(1):61‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen Q, Ou K, Guan Q, Zhang F. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas with liver metastasis: a case report. Chin Med J. 2008;121(9):853‐854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Soto Iglesias S, Baltar Arias R, Vázquez Rodríguez S, et al. Virchow’s node as the form of onset of squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;32(10):693‐696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Al‐Shehri A, Silverman S, King KM. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas. Curr Oncol. 2008;15(6):293‐297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Adachi K. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a case report. JOP. 2011;12(2):181‐184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Terada T. Adenosquamous carcinoma and pure squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas: report of two cases. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2010;4(3):369‐373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bideau K, Metges J‐P, Bayle S, et al. Treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas with gemcitabine. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30(10):1217‐1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Itani KM, Karni A, Green L. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3(5):512‐515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Koduri VG, Ravi TJ. Squamous‐cell carcinoma of the pancreas: report of a case and review of ERCP findings. Endoscopy. 1994;26(3):333‐334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ben Kridis W, Khanfir A, Toumi N, Ben Amar M, Boudawara T, Frikha M. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Intern Med. 2015;54(11):1357‐1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mehta M, Sinha J, Ogawa M, Ganguly A, Xiang D, Poddar N. Unusual case of squamous cell carcinoma of pancreas with review of literature. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2018;46(4):426e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aurello P, Petrucciani N, D’Angelo F, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Am Surg. 2012;78(5):E284‐E285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bralet MP, Terris B, Brégeaud L, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma and lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas. Virchows Arch. 1999;434(6):569‐572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Colarian J, Fowler D, Schor J, Poolos S. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas with cystic degeneration. South Med J. 2000;93(8):821‐822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brayko CM, Doll DC. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas associated with hypercalcemia. Gastroenterology. 1982;83(6):1297‐1299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. da Fonseca J, Brito MJ, Castro C, et al. Pancreatic squamous carcinoma mimicking a bleeding duodenal ulcer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51(3):362‐363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gupta RK, Wakefield SJ, Fauck R, Stewart RJ. Immunocytochemical and ultrastructural findings in a case of rare carcinoma of the pancreas with predominance of malignant squamous cells in an intraoperative needle aspirate. Acta Cytol. 1989;33(2):153‐156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marucci G, Betts CM, Liguori L, Eusebi V. Basaloid carcinoma of the pancreas. Virchows Arch. 2005;446(3):322‐324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Morgan J, Amazon K, Termin L. Squamous cell carcinoma infiltrating a pancreatic pseudocyst. South Med J. 1989;82(9):1161‐1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pedrajas JM, Valverde JJ, Téllez MJ, Castaño A, Pieltain R, Fernández‐Cruz A. Epidermoid carcinoma of the pancreas associated with malignant humoral hypercalcemia. Rev Clin Esp. 1993;193(2):73‐75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Raghavapuram S, Vaid A, Rego RF. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Pancreas: Mystery and Facts. J Ark Med Soc. 2015;112(3):42‐43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sears HF, Kim Y, Strawitz J. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas. J Surg Oncol. 1980;14(3):261‐265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Winder JS, Kulaylat AN, Schubart JR, Hal HM, Pauli EM. Management of non‐acute gastrointestinal defects using the over‐the‐scope clips (OTSCs): a retrospective single‐institution experience. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(6):2251‐2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Beyer KL, Marshall JB, Metzler MH, Poulter JS, Seger RM. Díaz‐Arias AA. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas. Report of an unusual case and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37(2):312‐318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Salla C, Chatzipantelis P, Konstantinou P, Karoumpalis I, Pantazopoulou A, Tsiotos G. EUS‐FNA contribution in the identification of autoimmune pancreatitis: a case report. JOP. 2007;8(5):598‐604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Raghavapuram S, Vaid A, Rego RF Squamous cell carcinoma of pancreas: mystery and facts. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46(4):426‐429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Modi RM, Kamboj AK, Shen R, Krishna SG. Endosonography and confocal endomicroscopy of primary keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas. ACG Case Rep J. 2017;4:e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ntanasis‐Stathopoulos I, Tsilimigras DI, Georgiadou D, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas: A systematic review and pooled survival analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2017;79:193‐204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bixler HA, Castro MJ, Stewart J. Cytologic differentiation of squamous elements in the pancreas. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39(7): 536–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lowry CC, Whitaker HW, Greiner DJ. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas. South Med J. 1949;42(9):753‐757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wong JC, Lu D. Staging of pancreatic adenocarcinoma by imaging studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(12):1301‐1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Pancreatic cancer. The Lancet. 2011;378(9791):607‐620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Loganadane G, Servagi‐Vernat S, Schernberg A, et al. Chemoradiation in rectal squamous cell carcinoma: Bi‐institutional case series. Eur J Cancer. 2016;58:83‐89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Osborne MC, Maykel J, Johnson EK, Steele SR. Anal squamous cell carcinoma: an evolution in disease and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(36):13052‐13059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wijnhoven B, van Lanschot J, Tilanus HW, Steyerberg EW, van der Gaast A. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for esophageal cancer: a review of meta‐analyses. World J Surg. 2009;33(12):2606‐2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gillen S, Schuster T, Meyer zum Büschenfelde C, Friess H, Kleeff J. Preoperative/neoadjuvant therapy in pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of response and resection percentages. PLoS Medicine. 2010;7(4):e1000267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jones OP. Adjuvant therapy in pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(40):14733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Neuzillet C, Gaujoux S, Williet N, et al. Pancreatic cancer: French clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50(12):1257–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Balaban EP, Mangu PB, Khorana AA, et al. Locally advanced, unresectable pancreatic cancer: american society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(22):2654‐2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kodavatiganti R, Campbell F, Hashmi A, Gollins SW. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2012;13(6):295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Klair JS, Kaur H, Vaid A, Rego R. Surviving primary pancreatic squamous cell carcinoma: a rare entity. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46(3):301‐303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]