Abstract

Background & Aims

The histone lysine demethylase 3A (KDM3A) demethylates demethylates H3K9me1 and H3K9Me2 to increase gene transcription and is upregulated in tumors, including pancreatic tumors. We investigated its activities in pancreatic cancer cell lines and its regulation of the gene encoding doublecortin calmodulin-like kinase 1 (DCLK1), a marker of cancer stem cells.

Methods

We knocked down KDM3A in MiaPaCa-2 and S2–007 pancreatic cancer cell lines and overexpressed KDM3A in HPNE cells (a human pancreatic cell line); we evaluated cell migration, invasion, and spheroid formation under hypoxic and normoxic conditions. Nude mice were given orthotopic injections of S2–007 cells, with or without (control) knockdown of KDM3A, and HPNE cells, with or without (control) overexpression of KDM3A; tumor growth was assessed. We analyzed pancreatic tumor tissues from mice and pancreatic cancer cell lines by immunohistochemistry and immunoblotting. We performed RNA-seq analysis of MiaPaCa-2 and S2–007 cells with knockdown of KDM3A and evaluated localization of DCLK1 and KDM3A by immunofluorescence. We analyzed the cancer genome atlas for levels of KDM3A and DCLK1 mRNA in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) tissues and association with patient survival time.

Results

Levels of KDM3A were increased in human pancreatic tumor tissues and cell lines, compared with adjacent non-tumor pancreatic tissues such as islet and acinar cells. Knockdown of KDM3A in S2–007 cells significantly reduced colony formation, invasion, migration, and spheroid formation, compared with control cells, and slowed growth of orthotopic tumors in mice. We identified KDM3A-binding sites in the DCLK1 promoter; S2–007 cells with knockdown of KDM3A had reduced levels of DCLK1. HPNE cells that overexpressed KDM3A formed foci and spheres in culture and formed tumors and metastases in mice, whereas control HPNE cells did not. Hypoxia induced sphere formation and increased levels of KDM3A in S2–007 cells and in HPNE cells that overexpressed DCLK1, but not control HPNE cells. Levels of KDM3A and DCLK1 mRNA were higher in human PDAC than non-tumor pancreatic tissues and correlated with shorter survival times of patients.

Conclusions

We found human PDAC samples and pancreatic cancer cell lines to overexpress KDM3A. KDM3A increases expression of DCLK1, and levels of both proteins are increased in human PDAC samples. Knockdown of KDM3A in in pancreatic cancer cell lines reduced their invasive and sphere-forming activities in culture and formation of orthotopic tumors in mice. Hypoxia increased expression of KDM3A in pancreatic cancer cells. Strategies to disrupt this pathway might be developed for treatment of pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: epigenetics, gene regulation, oncogene, repression

Lay Summary

We found levels of histone lysine demethylase 3A (KDM3A), a transcriptional regulator, to be increased in pancreatic cancer cells and human pancreatic tumors. KDM3A increases activities of cells that contribute to tumor formation.

Introduction

About 55,440 patients in 2018 were diagnosed with pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC)1 and most of them are projected to die within 5 years2. Most of the PDAC patients will die due to metastasis to the liver, lung and peritoneum3. PDAC is difficult to identifyearly in its natural history, leading to late diagnoses where curative treatment is limited, resulting in poor prognoses4. KRAS has been demonstrated to be commonly mutated in PDAC, and the question arises as to whether mutant KRAS is the only initiation factor for PDAC tumorigenesis5. Therefore, it is necessary to identify other factors including epigenetic marks that could influence pancreatic carcinogenesis.

Methylation of histone lysine is important for epigenetic-associated gene expression profiles in cancer6, 7 Histone methylation profiles have been demonstrated to be critical in developmental biology, neurological disorders and numerous cancer types8–10. Additionally, hypoxia modulates histone-modifying factor expression, leading to changes in histone marks. The hypoxia-inducible transcription factors (HIFs such as HIF1α and HIF1β) utilize co-activators that bind to hypoxia-responsive elements (HRE) of target genes, resulting in demethylation of histones ultimately leading to enhanced growth and differentiation in cancer 11. Recently, the pivotal role of Jumonji-C (Jmj) domain containing iron (II), 2-oxoglutarate (2OG)-dependent histone lysine demethylases (KDMs) in hypoxia response have been studied12. Hypoxia induces expression of four KDM enzymes (aso known as Jarid1b, Jmjd1a, Jmjd2b, and Jmjd2c) through the direct binding of HIF to the HREs present at their promoter regions13. Many cancers overexpress members of the Jmjd2 family of KDMs14. Their inhibition suppresses the growth of tumor cells, suggesting the therapeutic implications of targeting these proteins12, 15, 16. KDM3A (lysine demethylase 3A or JMJD1A or JHDM2A) is involved in regulating gene expression in numerous biological processes by demethylating mono- or di-methylated H3K917, 18 While KDM3A seems to selectively regulate gene expression, chromatin modifiers often lack intrinsic sequence recognition specificity. Therefore, understanding how KDM3A specifically regulates gene expression is an area of current inquiry and vital for understanding epigenetics in human disease. KDM3A activity is deregulated in several cancers, including prostate7, 18, breast19 and Ewing’s sarcoma20, 21. KDM3A regulates several transcription factors such as PPARG, KLF2, ESR1, and HOXA113, 18, 22–25. Emerging evidence suggests that epigenetic modifications by histone demethylases play pivotal roles in modulating gene expression19, 26, ultimately regulating both biological and pathological processes that include embryonic development, stem cell self-renewal and differentiation, genome integrity, and tumorigenesis9, 27.

Current literature indicates the presence of small populations of cancer-initiating cells (or also known as CSC) that are believed to be accountable for tumor initiation and progression as well as resistance to chemotherapy and radiation. Pancreatic CSCs can grow in ultra-low attachment culture dishes to form multicellular spheroids called pancospheres28, 29. In this regard, the protein doublecortin calmodulin-like kinase 1 (DCLK1) has been shown to mark a morphologically distinct subpopulation of cells with stem-like properties in preinvasive PDAC30, 31. DCLK1 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in human pancreatic cells through a miR-200a-dependent mechanism32 and plays a critical role in CSCs by in vivo lineage tracing33–35. With respect to PDAC, subpopulations of cells with tumor-initiating capacities have been identified in human PDAC cell lines as well as in primary xenografts of human PDAC36–38. To distinguish cells containing DCLK1 from non-stem cells, Baily et al39 demonstrated the temporal onset of cellular and functional heterogeneity in early PDAC. These studies have revealed a novel and morphologically distinct tumor-initiating PDAC cell type, marked by expression of DCLK139. Identification of the regulatory mechanisms and signaling pathways involved in CSCs are expected to help to identify and design novel agents that target this refractory cell population in PDAC.

In this study, we aim to elucidate the functional relationship of KDM3A with PDAC progression and stemness. We demonstrate, for the first time, crucial roles of KDM3A in PDAC oncogenic and stem-like properties using tissue culture and human PDAC tissues and show that KDM3A upregulates a CSC marker DCLK1 by binding to the DCLK1 promoter.

Material and Methods

Cells and culture condition

MiaPaCa-2 and Suit2–007 (S2–007) were cultured in RPMI media along with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma Aldrich) and 1% antibiotics (Fisher Scientific) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. All the cell lines used in this study were within 20 passages after receipt or resuscitation. The cell lines were authenticated at Arizona State University.

Luciferase expression vector and animal imaging

pcDNA 3.1(+) Luc2-tdT expression vector was obtained from Addgene. The expression vector stably transfected (Lipofectamine 2000) into control and KDM3A knock-down cells (S2–007 and MiaPaCa-2) and selected with Neomycin. The tdT.Luc2 expressing cells (1 ×106) were mixed with Matrigel (BD Bioscience). Five-week-old male athymic nude mice, purchased from Charles River Laboratory were utilized for in vivo experiments. They were maintained with water and standard mouse chow ad libidum and used in protocols approved by the University of Kansas Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The cells were orthotopically injected into the pancreas of nude mice, allowing for two weeks to develop a palpable tumor40. After two weeks, D-Luciferin (150 μg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally before imaging by the IVIS Imaging system.

Results

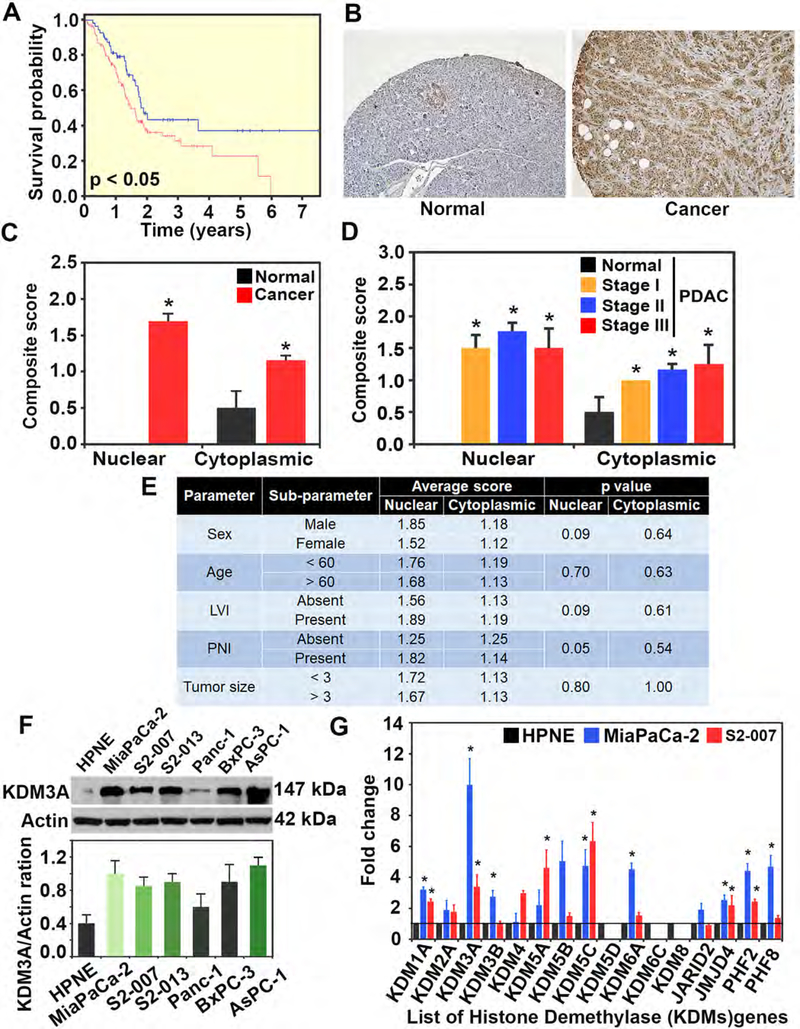

KDM3A is upregulated in PDAC

We first analyzed the cancer genome atlas (TCGA) datasets and observed decreased survival in PDAC correlates with elevated expression of KDM3A (Figure 1A). In addition, immunohistochemistry analysis showed low levels of KDM3A expression in acinar cells of the pancreas, while islet cells showed moderate expression. More importantly, KDM3A protein was present in the cytoplasm in normal pancreas. However, in the case of PDAC tissues, there were significantly higher levels of KDM3A in both nucleus and cytoplasm (Figures 1B and C). Nuclear expression of KDM3A was high compared to cytoplasmic expression in all stages of PDAC (Figure 1D). Further, KDM3A expression did not correlate significantly with patient characteristics, such as sex, age, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, and tumor size (Figure 1E).

Figure 1. Upregulation of KDM3A in PDAC.

(A) TCGA data of survival with KDM3A in PDAC: Patients with high expression of KDM3A is significantly (p < 0.05) correlated with poor survival probability as compared to low KDM3A expression.

(B) Immunohistochemistry for KDM3A showing that KDM3A is overexpressed in PDAC tissues when compared to adjacent normal tissues.

(C) Quantification of Immunohistochemistry for KDM3A showing that nuclear and cytoplasmic expression of KDM3A is significantly increased in PDAC tissues as compared to the normal pancreas (p < 0.01).

(D) Quantification of Immunohistochemistry for KDM3A showing that KDM3A is overexpressed at all stages of PDAC tissues as compared to the normal pancreas (p < 0.01).

(E) Quantification of Immunohistochemistry for KDM3A showing that KDM3A expression is not correlated with age, sex, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, tumor size of patients.

(F) Western blot of KDM3A in multiple human PDAC cell lines in comparison with a human non-cancerous pancreatic ductal cell line (HPNE). A summary of densitometric analyses of KDM3A protein levels is shown below the blot.

(G) KDM3A gene expression data in PDAC cells in comparison to other KDMs: Fold changes of gene expression using qPCR data suggested that KDM3A is upregulated higher than other KDMs in both S2–007 and MiaPaCa-2 cells (p < 0.05).

Next, using western blotting we examined KDM3A protein expression in multiple human PDAC cell lines and compared it with human non-cancerous pancreatic ductal cell line (HPNE) (Figure 1F). KDM3A protein expression was upregulated in human PDAC cell lines compared to HPNE as quantified by densitometry. KDM3A levels were significantly higher than other KDM family members in PDAC cell lines (Figure 1G) indicating KDM3A is specifically upregulated in PDAC. While KDM3A expression is elevated in MiaPaCa-2 compared to other PDAC cell lines, the relationship with aggressiveness was dependent on the cellular derivation from the primary tumor. MiaPaCa-2 is derived from primary PDAC41, while S2–007 is derived from a metastatic PDAC lesion within the liver. While such a correlation is not fully characterized, we felt these two cell lines would be appropriate for our studies.

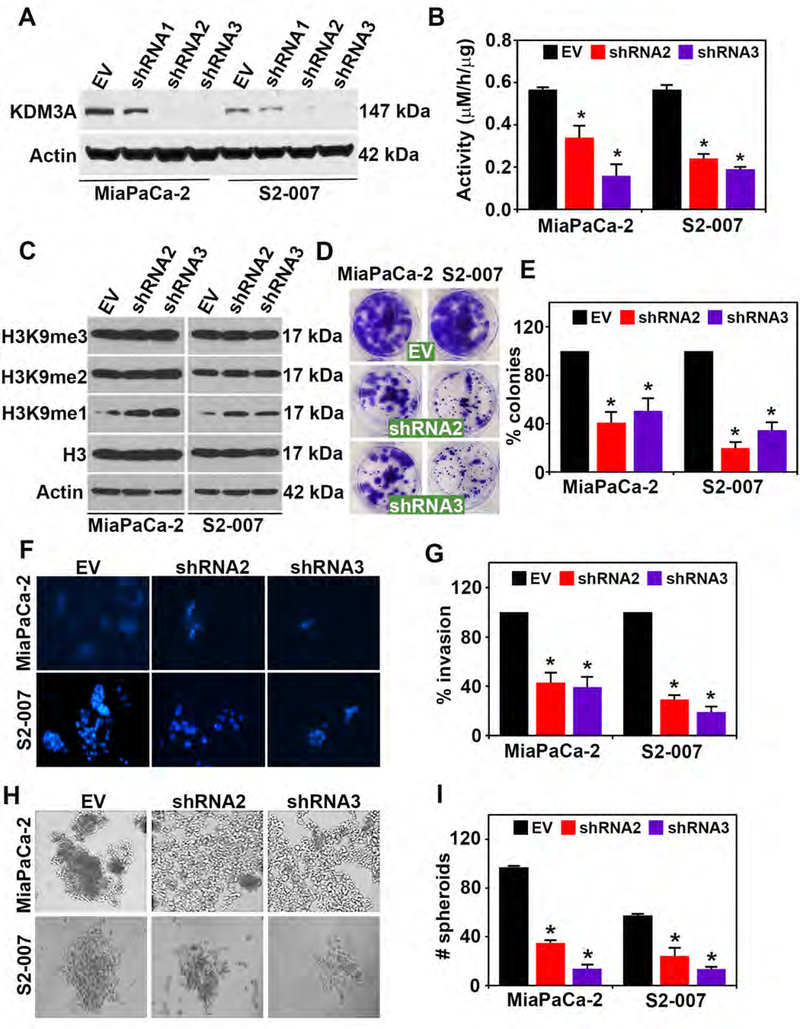

KDM3A knockdown inhibits malignant properties of PDAC cells

To investigate biological effects of KDM3A knockdown, we first validated two shRNA (shRNA2 and shRNA3) specific to human KDM3A, which successfully reduced protein levels of KDM3A in both S2–007 and MiaPaCa2 human PDAC cell lines (Figure 2A). Quantitative RT-PCR analyses for Jumonji domain KDM family of genes confirmed the reduction in KDM3A mRNA only by shRNA 2 and 3 in both MiaPaCa2 and S2–007 cells (Supplementary Figures 1A and B). Knockdown of KDM3A by both shRNA2 and shRNA3 significantly decreased the enzymatic activity as measured by formaldehyde formation in both S2–007 and MiaPaCa2 (Figure 2B). This was due to the increased availability of substrate H3K9me1 after inhibition of KDM3A (Figures 2C). It is also noted that H3K9me2 showed little or no change, suggesting KDM3A demethylates only H3K9me1 methylated histone marks (Figure 2C). We then demonstrated that knockdown of KDM3A in S2–007 cells significantly reduced colony formation (Figure 2D and E), cell invasion (Figure 2F and G), and spheroid formation (Figure 2H and I), in comparison to the empty vector control. Knockdown of KDM3A also inhibited cell migration in scratch plate assays in both S2–007 and MiaPaCa-2 cells (Supplementary Figure 2A and B).

Figure 2. KDM3A knockdown inhibits malignant properties of PDAC cells.

(A) Western blot analysis for KDM3A in MiaPaCa-2 and S2–007 cells showing shRNA 2 and shRNA 3 efficiently lowered expression of KDM3A protein levels in comparison to an empty vector.

(B) Knockdown of KDM3A (shRNA 2 and shRNA 3) resulted in reduced KDM3A enzyme activity seen by measuring formaldehyde levels and increased substrate H3K9me1, a substrate for KDM3A, without altering H3, H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 levels in MiaPaCa-2 and S2–007 cells (p < 0.05).

(C) Knockdown of KDM3A (shRNA 2 and 3) reduced the specific substrate of KDM3A in particular H3K9me1, not the other substrate H3K9me2. H3K9me3 is not the specific substrate of KDM3A. Knockdown of KDM3A also inhibited (D-E) colony formation, (F-G) invasion and (H-I) spheroid formation in MiaPaCa-2 and S2–007 cells in PDAC cell lines

We further demonstrated that reintroduction of KDM3A in KDM3A-knockdown S2–007 cells by shRNA3 (sh3RE1) rescued pancosphere formation reduced by KDM3A knockdown, strongly suggesting that the observed phenotypes formed by KDM3A-specific shRNA3 are not off-target effects (Supplementary Figures 3A and B).

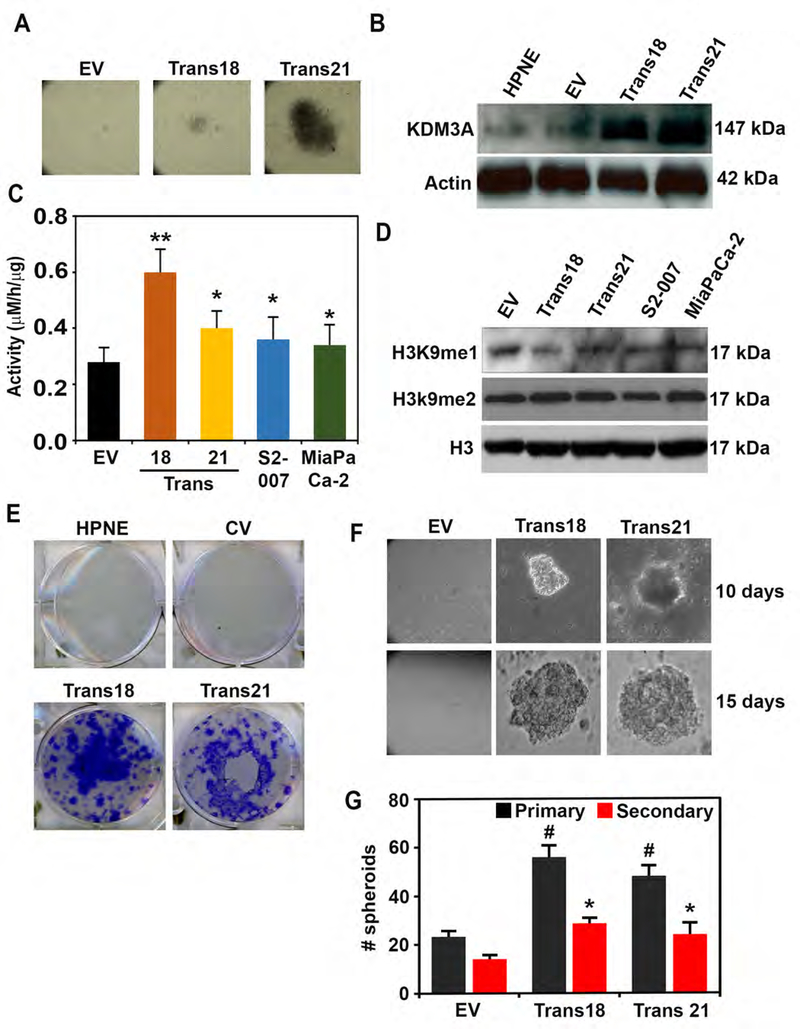

Overexpression of KDM3A induces transformation in non-cancerous pancreatic ductal cells

We next examined the effects of KDM3A overexpression on malignant characteristics of PDAC. First, transduction of a KDM3A cDNA-encoding lentiviral vector into non-cancerous pancreatic ductal HPNE cells transformed cells to form foci; we selected two colonies (Trans 18 and 21) and expanded them to culture for further experiments (Figure 3A). Both transformed foci expressed KDM3A at high levels (Figure 3B) and showed increased KDM3A enzymatic activity (Figure 3C). The levels of substrate concentrations, particularly in H3K9me1 but not H3K9m2, were lower in Trans 18 and 21 cells than in empty vector-infected HPNE cells (Figure 3D). Both clones demonstrated increased colony- and spheroid-forming potential (Figures 3E–G). They also exhibited accelerated migration and wound closure, as well as invasion, within 24–48 hours (Supplementary Figure 4A–C). Moreover, we confirmed that depletion of KDM3A in KDM3A-overexpressing HPNE trans 18 cells by siRNA1 (si1) reduced pancosphere formation, strongly suggesting that the observed phenotypes induced by KDM3A overexpression are not off-target effects (Supplementary Figures 5A and B). Additionally, increased levels of several hallmarks of PDAC, including phospho-EGFR, phospho-Akt, 14–3-3σ, and CA-19–9, were found in both Trans 18 and 21 cells, as compared to parental HPNE cells (Supplementary Figure 6).

Figure 3. Overexpression of KDM3A induces transformation in non-cancerous pancreatic ductal cells.

(A) Overexpression of KDM3A in HPNE resulted in forming two transformed clones of Trans21 and Trans18.

(B) Western blot image showing KDM3A overexpression in Trans18 and Trans21 compared to parental HPNE cells and those carrying empty vector (EV).

(C) Increased KDM3A enzyme activities observed in both Trans21 and Trans 18 HPNE clones as well as MiaPaCa2 and S2–007 cells in comparison with HPNE EV (empty vector) cells (p < 0.05)

(D) H3K9Me1 (a substrate of KDM3A) levels are lower and H3K9me2 levels were unchanged among cell lines examined.

(E) Overexpression of KDM3A increased colony formation of Trans 18 and Trans 21 colonies

(F-G) Overexpression of KDM3A increased spheroid forming potential (size and number) of Trans 18 and Trans 21 (p < 0.05).

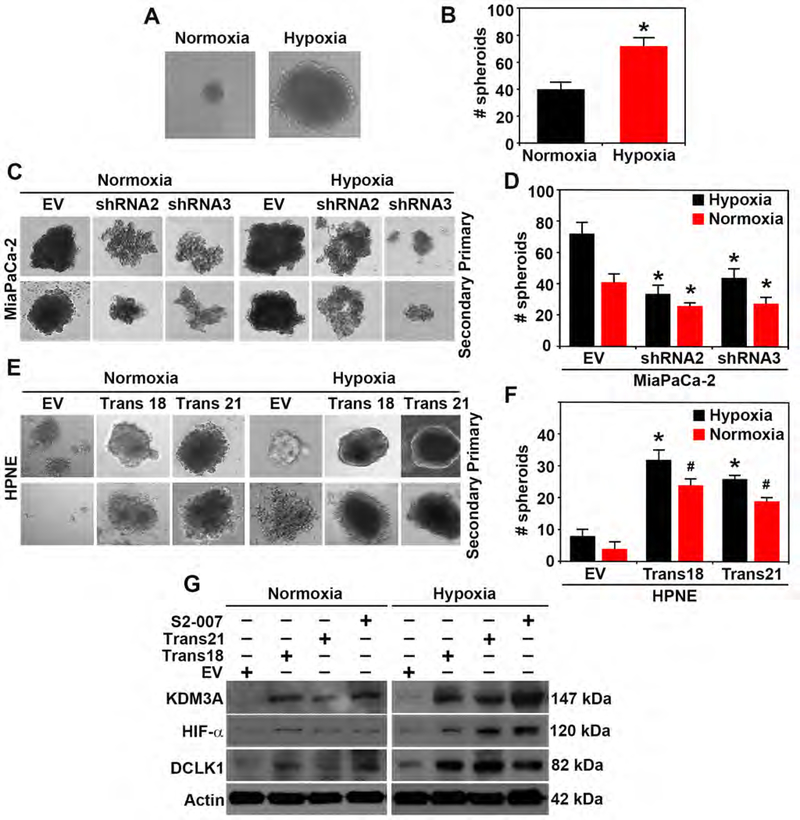

Hypoxia induces pancosphere formation and increased KDM3A in PDAC and transformed HPNE cells

Since hypoxia increases KDM3A expression13, we examined the contributions of KDM3A in hypoxia-induced spheroid formation. First, we confirmed that hypoxic conditions significantly increased the spheroid formation of MiaPaCa-2 cells. Spheroid formation was significantly increased with hypoxia (Figures 4A and B), while KDM3A knockdown (shRNA2 and shRNA3) inhibited primary and secondary spheroid-forming ability in both hypoxic and normoxic conditions (Figures 4C and D). Overexpression of KDM3A in transformed HPNE clones (Trans 18 and 21) showed increased spheroid forming potential (primary) and self-renewability of the spheroids (secondary) in both hypoxic and normoxic conditions in comparison to empty vectors (Figures 4E and F). We next examined whether there was correlation of KDM3A levels with HIF1a, a hypoxia-related protein, and DCLK1, a CSC-related protein. In normoxic conditions, proteins levels of KDM3A were positively correlated with HIF1-α and DCLK1, while hypoxia further enhanced protein levels of KDM3A, HIF1-α, and DCLK1 in S2–007 and KDM3A-overexpressing Trans 18 and 21 cells (Figure 4G). These results strongly suggest the involvement of KDM3A in stem-like properties of PDAC cells and a possible link of KDM3A with HIF1α and/or DCLK1 in hypoxia.

Figure 4. Hypoxia induces pancosphere formation and increased KDM3A in PDAC and transformed HPNE cells.

(A & B) Pancosphere formation (size and number) is significantly increased during hypoxic conditions (p < 0.05).

(C-D) Primary and secondary spheroids formation (size and number) are significantly inhibited by silencing of KDM3A (shRNA2 and shRNA3) in hypoxic and normoxic conditions in MiaPaCa2 PDAC cells (p < 0.05).

(E-F) Overexpression of KDM3A in HPNE non-cancerous cell (Trans18 and Trans21 transformed clones) showed a significant increase in size and number of spheroids (p < 0.05) in both normoxic and hypoxic conditions in comparison to empty vectors (EV).

(G) Western blot analysis of KDM3A, HIF-α and DCLK1 in S2–007, Trans18 and Trans21 HPNE in comparison to EV during normoxic and hypoxic condition demonstrating hypoxia increased the expressions of those proteins.

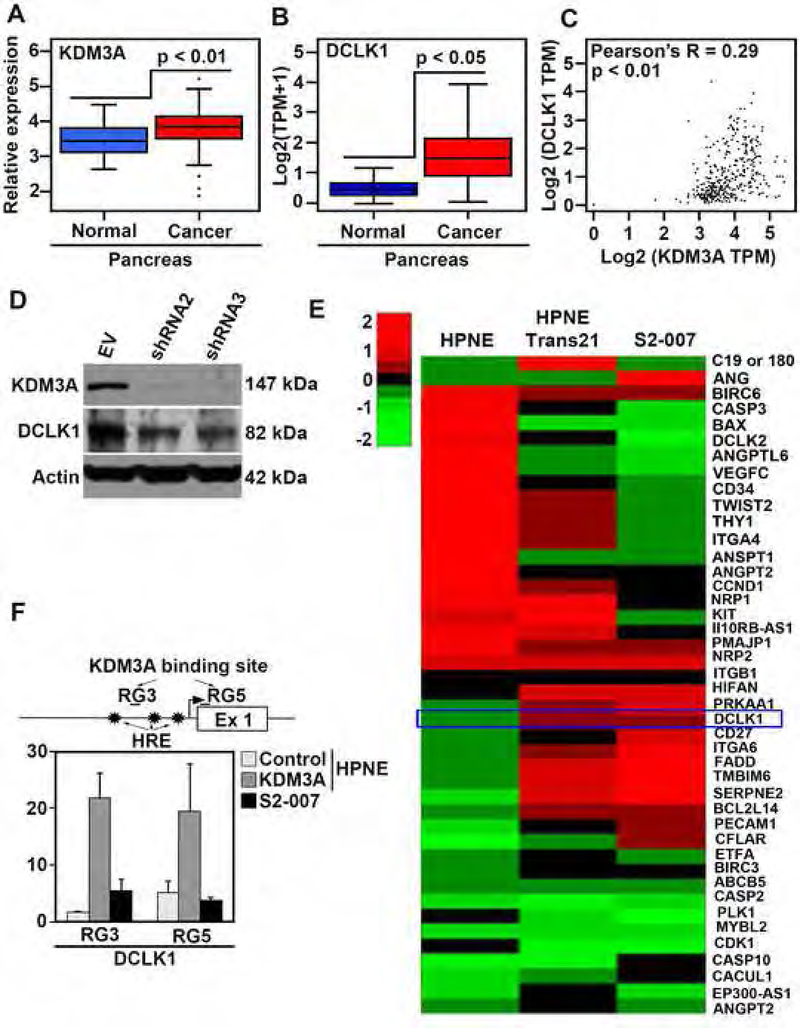

KDM3A transcriptionally regulates mRNA expression of DCLK1, a pancreatic stem cell marker

To investigate a link between KDM3A and DCLK1, we examined mRNA expression levels of KDM3A and DCLK1 using available microarray data published by Moffitt et al42 as well as the TCGA database. Both KDM3A and DCLK1 mRNA expression in PDAC was higher than in normal tissues (Figures 5A and B). Additionally, there was a positive correlation (Pearson’s R = 0.29, p < 0.01) between KDM3A and DCLK1 mRNA expression in human PDAC tissues (Figure 5C). Immunohistochemistry result using human PDAC tissues supports the above finding DCLK1 levels were higher in PDAC than adjacent normal tissues (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure 7A). Moreover, immunofluorescence showed coexpression of KDM3A with DCLK1 in PDAC tissues (Supplementary Figure 7B) and cells (Supplementary Figure 7C). To further examine the positive correlation between KDM3A and DCLK1, we knocked down KDM3A and examined DCLK1 protein levels. Knockdown of KDM3A in S2–007 cells reduced DCLK1 levels (Figure 5D). Correspondingly, Trans 18 and 21 cells expressed higher levels of DCLK1 than HPNE cells (Figure 4G). ACLK1 protein levels in the clones are similar to that seen in S2–007 PDAC cells. A clustergram representing RNA-seq data demonstrated up-regulation of DCLK1 in Trans21 HPNE and S2–007 cells (Figure 5E). ChIP-seq data also confirmed that KDM3A bound to genomic DNA sequences within the DCLK1 gene in both Trans 21 and S2–007 cells (Supplementary Figure 7D). Chromatin-immunoprecipitation (ChIP) using a KDM3A antibody showed that a RG3 region in the promoter and a RG5 region in exon 1 of the DCLK1 gene were bound with KDM3A near the HIF-responsive elements (HREs) (Figure 5F). These results strongly suggest that KDM3A binds to the DCLK1 promoter to upregulate DCLK1 expression.

Figure 5. KDM3A transcriptionally regulates mRNA expression of DCLK1, a pancreatic stem cell marker.

(A) A boxplot showing KDM3A is upregulated in PDAC comprised of normal pancreatic tissue (n=46) and primary pancreatic adenocarcinomas (n=145) (p < 0.01). The data is acquired through microarray analysis performed by Moffitt et al.

(B) A boxplot showing significantly increased expression of DCLK1 in TCGA PDAC (PAAD) samples as compared to the normal pancreas (TCGA-PAAD normal and GTEx pancreas) (p < 0.05).

(C) The TCGA database showed a positive correlation between KDM3A and DCLK1 in PDAC (R = 0.29, p < 0.01).

(D) Knockdown of KDM3A in S2–007 cells (shRNA2 and shRNA3) showing the reduced expressions of KDM3A and DCLK1.

(E) Clustergram of RNA-seq data of HPNE overexpressed HPNE and S2–007 cells showing DCLK1 upregulation in PDAC cells associated with KDM3A overexpression.

(F) ChIP assay using KDM3A antibody shows one site at the promoter and another in Exon 1 in DCLK1 that is pulled down by anti-KDM3A antibody. The HIF-responsive element (HRE) is located in the promoter region downstream from the RG3 site.

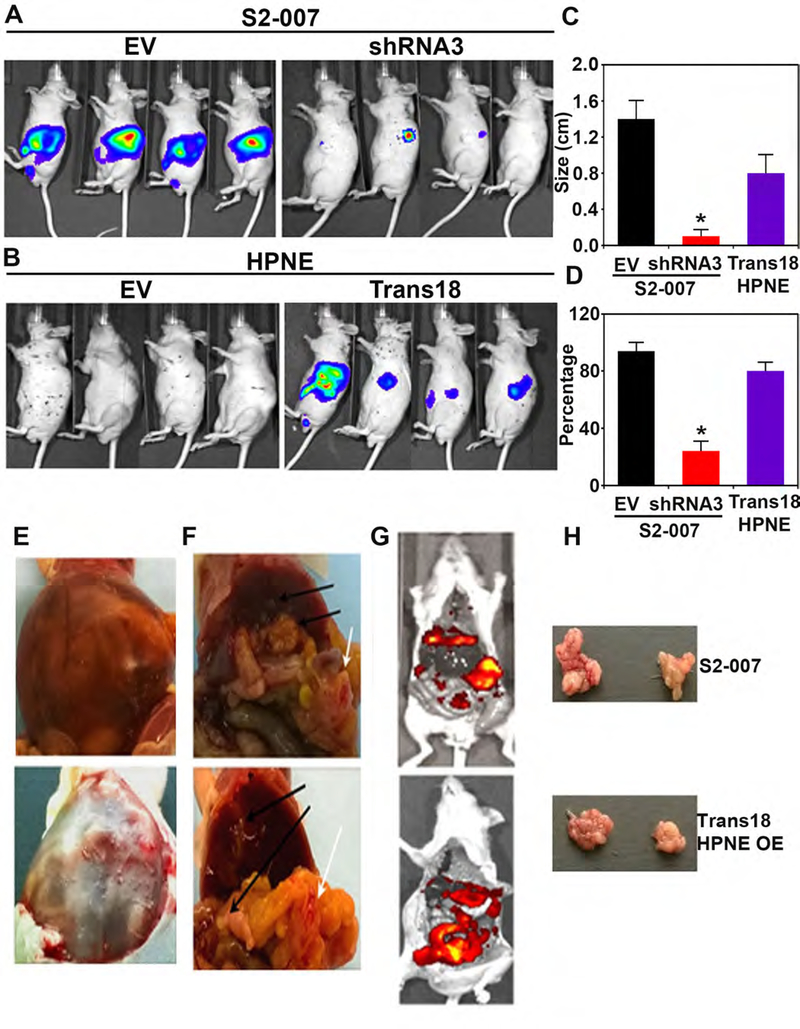

KDM3A silencing inhibits tumor formation while overexpression of KDM3A stimulates tumor development

Finally, we examined the in vivo effects of KDM3A in PDAC progression. For this, luciferase gene-labeled S2–007 cells where KDM3A was knocked down using shRNAwere orthotopically injected, and tumor formation was measured following D-Luciferin injection. Parental S2–007 cells used as a positive control. KDM3A knockdown significantly inhibited the tumor growth of S2–007 cells (Figures 6A and C–D). Also, Trans 18 cells, overexpressing KDM3A, formed tumors, while parental HPNE cells failed to do so, further supporting the oncogenic potential of KDM3A in vivo (Figures 6B and C–D). Interestingly, liver and lung metastases were detected in mice injected with S2–007 or Trans 18 HPNE cells (Figures 6E–H). We also detected high levels of KDM3A and DCLK1, as well as the proliferation marker PCNA, in Trans 18 HPNE and S2–007 tumors (Supplementary Figure 8A). Moreover, KDM3A levels in Trans 18 HPNE and S2–007 tumors were even higher in lung and liver metastases compared with corresponding primary tumors (Supplementary Figure 8B). Further, DCLK1 and KDM3A coexpress in S2–007 tumor cells (Supplementary Figure 8C). Additionally, KDM3A and DCLK1 protein expression were also increased in PanIN and PDAC tissues collected from KPC mice (Supplementary Figure 8D).

Figure 6. KDM3A silencing inhibits tumor formation while overexpression of KDM3A stimulates tumor development.

(A) Luciferase-labeled S2–007 cells (5 × 108) with knockdown of KDM3A (right) or without (left) were orthotopically injected into the pancreas of nude mice. Representative images of in vivo imaging of luciferas-expressing S2–007 cells.

(B) Luciferase-labeled control HPNE (EV, left) or Trans18 HPNE (right) cells (5 × 108) were orthotopically injected into the pancreas of nude mice. Representative images of in vivo imaging of luciferase-expressing HPNE cells.

(C) A summarized graph showing tumor size of each group (n=4).

(D) A summarized graph showing the percentage of tumor size of each group (n=4).

(E-G) Luciferase fluorescence of peritoneal cavity metastasis of Trans18 HPNE cells. Luciferase fluorescence of peritoneal cavity metastasis of S2–007 cells without knockdown of KDM3A.

(H) Tumor pictures of S2–007 and HPNE OE (Trans 18) clone in the orthotopic model in mice.

N-oxalyl glycine (NOG) is a putative inhibitor of KDMs that nonspecifically inhibits Jumanji domain proteins, including KDM3A43, 44, and also decreases tumor growth45, 46 Using NOG, we synthesized an analog (PSNA) (Supplementary Figure 9A). We first performed molecular docking studies to evaluate potential binding of these compounds to KDM3A and found that the compound, PNSA, showed a more favorable binding energy (−10.8 Kcal/mol respectively) than NOG (−5.3 Kcal/mol) with increased hydrogen bond formation to stabilize the interaction (Supplementary Figure 9B). Moreover, PNSA showed a better inhibitory activity than NOG against KDM3A in the in vitro enzyme assay (Supplementary Figure 9C). Next, we examined the biological activity of PNSA and found that PNSA inhibited proliferation and colony formation of MiaPaCa-2 and S2–007 cell lines (Supplementary Figures 9D and E). PNSA treatment also reduced DCLK1 and KDM3A protein expression in MiaPaca-2 and S2–007 cells (Supplementary Figure 9F). Moreover, nude mice orthotopically injected with S2007 cells and intraperitoneally treated with PNSA daily for 21 days revealed a significant reduction of the tumor growth, as compared with mice treated with DMSA/buffer vehicle (Supplementary Figures 9G and H).

Discussion

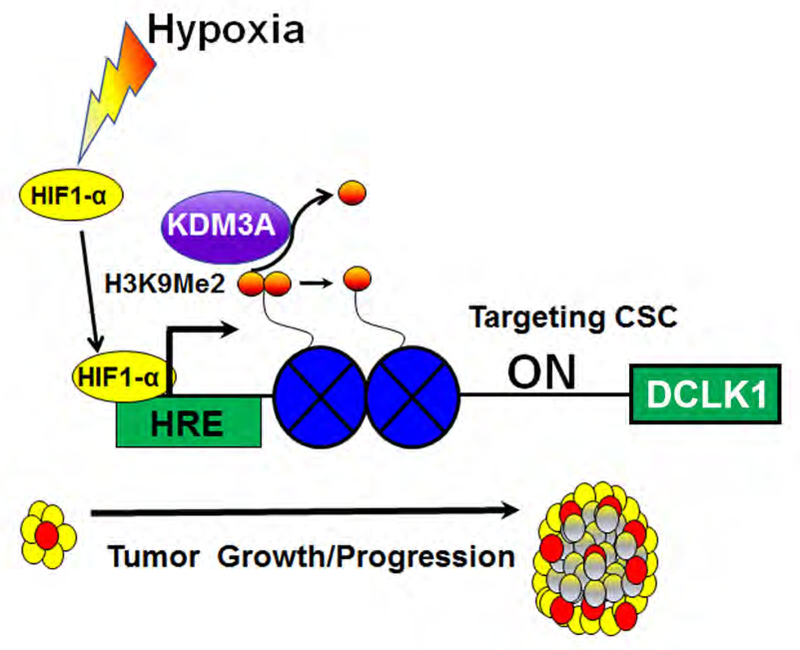

Our findings strongly suggest an oncogenic function for KDM3A in promoting pancreatic tumorigenesis. KDM3A regulates many biological and pathophysiological mechanisms involving sexual differentiation, germ cell development, obesity and chemoresistance14. It also promotes cancer progression by epigenetic regulation of gene expression13, 17, 47, 48. KDM3A demethylates histone marks H3K9me1 and H3K9Me2 thereby playing a central role in the histone code7. KDM3A is one of the histone demethylases which lacks a defined histone-binding domain and may require assistance from DNA/histone binding proteins27, 49 KDM3A demethylates mainly repressive marks of H3K9me1 in PDAC, which is presumably the mechanism regulating malignant properties. Among the partners of KDM3A are the hypoxia-inducible factors. Hypoxic regulation of KDM3A acts as an amplifier to facilitate tumor growth, not only by stimulating hypoxia-related genes13 but also by enhancing stemness through DCLK1 expression.

In previous studies, it has been suggested that DCLK1 acts as a tumor-initiating cell marker in different cancer types32, 50, 51. It is suggested that both preinvasive and invasive PDAC rely on specialized subpopulations of DCLK1-expressing cells with capabilities directly related to CSC 39. In this regard, KDM3A supports a CSC marker by regulating expression of SOX2 in ovarian cancer19. Our findings are the first to demonstrate that KDM3A could be crucial for the progression of PDAC tumorigenesis via regulation of DCLK1. KDM3A demethylates H3K9me1 in PDAC cells and binds to the promoter regions in DCLK1. Our data suggest a cooperation between HIF1α and KDM3A to control hypoxia-induced stemness via upregulation of DCLK1. Under hypoxia, HIF1α activates KDM3A52, which in turn, increased DCLK1 mRNA expression. Hypoxia-activated oncogenes are regulated by histone demethylases has been previously described13, 53, 54.

These molecular changes result in clinically important phenotypic changes as well. KDM3A knockdown inhibited invasion and stemness and also tumor formation. Moreover, overexpression of KDM3A transformsed cells and promotesd tumor formation. Taken together, our data suggest that KDM3A-mediated upregulation of DCLK1 is important for tumorigenesis of PDAC during hypoxia, and is critical for tumor initiation, metastasis, and progression.

To further understand the involvement of KDM3A in PDAC tumorigenesis, we used NOG and developed analogs that could bind to KDM3A at specific motifs of the enzyme and showed a reduction of KDM3A and DCLK1, leading to inhibited tumor formation in orthotopic mouse models. To demonstrate the in vivo significance of KDM3A on tumor development, we could not use KDM3A knockout mice, since KDM3A knockout mice have low sperm counts due to arrested spermatogenesis and apoptosis of developing germ cells, which complicates generation of cohorts for spontaneous tumorigenesis experiments55. Therefore, we took an approach of using a KDM3A inhibitor to further explore the in vivo role of KDM3A in PDAC progression. Our data using a NOG analog, PNSA, strongly promotes the idea that inhibition of KDM3A regulating PDAC stemness may have profound therapeutic implications.

In summary, this study describes a new role for histone demethylase KDM3A in the regulation of DCLK1, as well as PDAC stemness and progression. This newly described molecular mechanism appears especially relevant to the hypoxic environment of PDAC (Figure 7). Given the aggressiveness of PDAC, understanding the roles of epigenetic marks in PDAC malignancy could have important implications for the regulation of pathways promoting PDAC progression. Hence, the development of inhibitors to this regulatory pathway may provide new opportunities for therapeutic targeting of PDAC via KDM3A.

Figure 7. KDM3A regulating DCLK1 promoting tumorigenesis.

KDM3A transcriptionally regulate DCLK1 by binding with at the promoter region of DCLK1, promoting tumorigenesis in PDAC.

Supplementary Material

What you need to know.

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

The histone lysine demethylase 3A (KDM3A) regulates gene expression and is upregulated in tumors. We investigated its activities in pancreatic cancer cell lines and its regulation of the doublecortin calmodulin-like kinase 1 gene (DCLK1), a marker of cancer stem cells.

NEW FINDINGS

Human and mouse pancreatic tumor tissues and cells have increased levels of KDM3A. KDM3A increases expression of DCLK1. Knockdown of KDM3A in in pancreatic cancer cells reduced their invasive and stem cell properties.

LIMITATIONS

This study was performed in mice and cell lines

IMPACT

Strategies reduce activities or expression of KDM3A might be developed for treatment of pancreatic cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by NIH grants CA 151727 (Dhar), CA182872, CA135559, and CA109269 (S. Anant); the U.S. Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-18-1-0031); the Kansas Bioscience Authority; the Thomas P. O’Sullivan Foundation; the Rod Rogers Pancreatic Cancer Charity, and grants from the Braden’s Hope Foundation and Midwest Cancer Alliance. Dr. Dhar was supported by a pilot project from the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant CA168524, which supports the Biospecimen Repository Shared Resource that provided the deidentified patient samples. The University of Kansas Medical Center-Genomics Core is supported by HD090216 and GM104936. We also acknowledge the help of undergraduate students Yuto Iwakuma and Ritu Agarwal from University of Kansas. We also gratefully acknowledge the generous gift of SUIT2 cell lines from Dr. Tony Hollingsworth (Eppley Cancer Center).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors disclose no conflicts.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material includes nine figures and material and method section can be found with this article online at

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yachida S, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. The pathology and genetics of metastatic pancreatic cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2009;133:413–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le N, Sund M, Vinci A, et al. Prognostic and predictive markers in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Digestive and Liver Disease 2016;48:223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eser S, Schnieke A, Schneider G, et al. Oncogenic KRAS signalling in pancreatic cancer. British journal of cancer 2014;111:817–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonda TJ, Ramsay RG. Directly targeting transcriptional dysregulation in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2015; 15:686–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson S, Fan L, Sahgal N, et al. The histone demethylase KDM3A regulates the transcriptional program of the androgen receptor in prostate cancer cells. Oncotarget 2017;8:30328–30343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albert M, Helin K. Histone methyltransferases in cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2010;21:209–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kooistra SM, Helin K. Molecular mechanisms and potential functions of histone demethylases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012;13:297–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedersen MT, Helin K. Histone demethylases in development and disease. Trends Cell Biol 2010;20:662–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factors in physiology and medicine. Cell 2012;148:399–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan DA, Giaccia AJ. Hypoxia, gene expression, and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2007;26:333–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krieg AJ, Rankin EB, Chan D, et al. Regulation of the histone demethylase JMJD1A by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha enhances hypoxic gene expression and tumor growth. Mol Cell Biol 2010;30:344–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sainathan S, Paul S, Ramalingam S, et al. Histone Demethylases in Cancer. Current Pharmacology Reports 2015;1:234–244. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berry WL, Janknecht R. KDM4/JMJD2 histone demethylases: epigenetic regulators in cancer cells. Cancer research 2013;73:2936–2942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cloos PA, Christensen J, Agger K, et al. The putative oncogene GASC1 demethylates tri- and dimethylated lysine 9 on histone H3. Nature 2006;442:307–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okada Y, Scott G, Ray MK, et al. Histone demethylase JHDM2A is critical for Tnp1 and Prm1 transcription and spermatogenesis. Nature 2007;450:119–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamane K, Toumazou C, Tsukada Y, et al. JHDM2A, a JmjC-containing H3K9 demethylase, facilitates transcription activation by androgen receptor. Cell 2006;125:483–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramadoss S, Guo G, Wang CY. Lysine demethylase KDM3A regulates breast cancer cell invasion and apoptosis by targeting histone and the non-histone protein p53. Oncogene 2017;36:47–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sechler M, Parrish JK, Birks DK, et al. The histone demethylase KDM3A, and its downstream target MCAM, promote Ewing Sarcoma cell migration and metastasis. Oncogene 2017;36:4150–4160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parrish JK, Sechler M, Winn RA, et al. The histone demethylase KDM3A is a microRNA-22-regulated tumor promoter in Ewing Sarcoma. Oncogene 2015;34:257–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang Y, Wang S, Zhao Y, et al. Histone H3K9 demethylase JMJD1A modulates hepatic stellate cells activation and liver fibrosis by epigenetically regulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Faseb j 2015;29:1830–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahajan K, Mahajan NP. ACK1/TNK2 tyrosine kinase: molecular signaling and evolving role in cancers. Oncogene 2015;34:4162–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohguchi H, Hideshima T, Bhasin MK, et al. The KDM3A-KLF2-IRF4 axis maintains myeloma cell survival. Nat Commun 2016;7:10258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wade MA, Jones D, Wilson L, et al. The histone demethylase enzyme KDM3A is a key estrogen receptor regulator in breast cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:196–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res 2011;21:381–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi Y, Whetstine JR. Dynamic regulation of histone lysine methylation by demethylases. Mol Cell 2007;25:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ponnurangam S, Dandawate PR, Dhar A, et al. Quinomycin A targets Notch signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer stem cells. Oncotarget 2016;7:3217–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rangarajan P, Subramaniam D, Paul S, et al. Crocetinic acid inhibits hedgehog signaling to inhibit pancreatic cancer stem cells. Oncotarget 2015;6:27661–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito H, Tanaka S, Akiyama Y, et al. Dominant Expression of DCLK1 in Human Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cells Accelerates Tumor Invasion and Metastasis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0146564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mwangi SM, Srinivasan S. DCAMKL-1: a new horizon for pancreatic progenitor identification. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2010;299:G301–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sureban SM, May R, Lightfoot SA, et al. DCAMKL-1 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human pancreatic cells through a miR-200a-dependent mechanism. Cancer Res 2011;71:2328–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen L, Kasai T, Li Y, et al. A model of cancer stem cells derived from mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. PloS one 2012;7:e33544–e33544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Driessens G, Beck B, Caauwe A, et al. Defining the mode of tumour growth by clonal analysis. Nature 2012;488:527–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schepers AG, Snippert HJ, Stange DE, et al. Lineage tracing reveals Lgr5+ stem cell activity in mouse intestinal adenomas. Science 2012;337:730–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hermann PC, Huber SL, Herrler T, et al. Distinct populations of cancer stem cells determine tumor growth and metastatic activity in human pancreatic cancer. Cell Stem Cell 2007;1:313–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olempska M, Eisenach PA, Ammerpohl O, et al. Detection of tumor stem cell markers in pancreatic carcinoma cell lines. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2007;6:92–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rasheed Z, Wang Q, Matsui W. Isolation of stem cells from human pancreatic cancer xenografts. J Vis Exp 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bailey JM, Alsina J, Rasheed ZA, et al. DCLK1 marks a morphologically distinct subpopulation of cells with stem cell properties in preinvasive pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology 2014;146:245–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghosh C, Paul S, Dandawate P, et al. Super-enhancers: novel target for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget 2019;10:1554–1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deer EL, Gonzalez-Hernandez J, Coursen JD, et al. Phenotype and genotype of pancreatic cancer cell lines. Pancreas 2010;39:425–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moffitt RA, Marayati R, Flate EL, et al. Virtual microdissection identifies distinct tumor- and stroma-specific subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Genet 2015;47:1168–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rose NR, Ng SS, Mecinovic J, et al. Inhibitor scaffolds for 2-oxoglutarate-dependent histone lysine demethylases. J Med Chem 2008;51:7053–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rose NR, Woon EC, Kingham GL, et al. Selective inhibitors of the JMJD2 histone demethylases: combined nondenaturing mass spectrometric screening and crystallographic approaches. J Med Chem 2010;53:1810–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamada S, Kim TD, Suzuki T, et al. Synthesis and activity of N-oxalylglycine and its derivatives as Jumonji C-domain-containing histone lysine demethylase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2009;19:2852–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hancock RL, Dunne K, Walport LJ, et al. Epigenetic regulation by histone demethylases in hypoxia. Epigenomics 2015;7:791–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuroki S, Matoba S, Akiyoshi M, et al. Epigenetic regulation of mouse sex determination by the histone demethylase Jmjd1a. Science 2013;341:1106–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tateishi K, Okada Y, Kallin EM, et al. Role of Jhdm2a in regulating metabolic gene expression and obesity resistance. Nature 2009;458:757–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim KY, Huerta SB, Izumiya C, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) latency-associated nuclear antigen regulates the KSHV epigenome by association with the histone demethylase KDM3A. J Virol 2013;87:6782–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakanishi Y, Seno H, Fukuoka A, et al. Dclk1 distinguishes between tumor and normal stem cells in the intestine. Nat Genet 2013;45:98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vega KJ, May R, Sureban SM, et al. Identification of the putative intestinal stem cell marker doublecortin and CaM kinase-like-1 in Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;27:773–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krieg AJ, Rankin EB, Chan D, Razorenova O, Fernandez S, Giaccia AJ. Regulation of the histone demethylase JMJD1A by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha enhances hypoxic gene expression and tumor growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:344–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wellmann S, Bettkober M, Zelmer A, et al. Hypoxia upregulates the histone demethylase JMJD1A via HIF-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008;372:892–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yuen A, Diaz B. The impact of hypoxia in pancreatic cancer invasion and metastasis. Hypoxia (Auckl) 2014;2:91–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu Z, Zhou S, Liao L, et al. Jmjd1a demethylase-regulated histone modification is essential for cAMP-response element modulator-regulated gene expression and spermatogenesis. J Biol Chem 2010;285:2758–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.