Abstract

Background

Assistive technology (AT) has the potential to support and enhance self-management of people living with dementia. However, a range of special and heterogeneous needs must be considered when designing and deploying AT for people with dementia, and consequently the involvement of end-users throughout the design process is essential to provide usable and effective AT solutions.

Objective

The ReACT study was conducted to investigate how a tailor-made app, the ReACT app, can be designed and deployed to meet the needs of people with dementia in relation to self-management.

Methods

This paper presents 4 steps of an iterative user-involving app design process. In the first step, a pilot study was conducted to explore the potential benefits and challenges of using existing off-the-shelf apps to support self-management when living with early-stage dementias. In the second step, focus group interviews provided in-depth understanding of the perspectives and needs of potential end-users of the app. The third step was a product benchmarking process, which served to further qualify the design process. Finally, results from these first 3 steps were included in the fourth step where the ReACT app was designed through an iterative codesign process. In total, 28 people with dementia, 17 family caregivers, and 10 professional caregivers were involved through these 4 iterative steps.

Results

The functionalities and the design of the ReACT app directly reflect the perspectives and needs of end-users in relation to self-management. Support of memory and structure in daily living were identified as main needs, and the ReACT app was designed as a holistic and adaptable solution with a tailor-made calendar as a key feature.

Conclusion

Based on this extensive iterative user-involving design process, the ReACT app has great potential to support and enhance self-management of people living with dementia. Further studies are needed to test and validate the usability and impact of the app, and methods for deployment and adoption of AT for people with dementia also need to be considered.

Keywords: Dementia, Assistive technology, Self-management, Rehabilitation, User-involving design

Introduction

Societies worldwide are faced with the challenge of providing suitable and affordable support and care for the fast-growing number of people living with dementia [1, 2]. Crucial breakthroughs are still awaited in the effort to find pharmaceutical treatments for the range of dementia diseases [2], but there is growing emphasis on how other methods and approaches, for example, psychosocial interventions, can play a crucial role in reducing the impact of dementia symptoms, and enable people with dementia and their supporters to cope and live with dementia [3, 4]. One of the advancing approaches is the use of assistive technology (AT) to support and enhance the capacity of people living with dementia, and this potential impact of technology is emphasized in international initiatives to counteract dementia [1, 5].

AT can be defined as “Any item, piece of equipment, software program, or product system that is used to increase, maintain, or improve the functional capabilities of persons with disabilities” [6], and it spans a wide variety of solutions, ranging from basic everyday low-tech devices to advanced high-tech hardware or software technology [6].

Both the technology industry and dementia researchers have growing interest in AT for people with dementia [7, 8], and AT is applied to meet a range of needs of people with dementia, for example, assisting management of everyday life, engagement in meaningful and pleasurable activities, and supporting professionals and organizations who provide health and social care for people with dementia [9]. However, as much as there is optimism that AT can be a key solution in the support, rehabilitation and care for people with dementia, there is also a growing awareness of the lack of high-quality research to provide evidence-based solutions and methods within this field [9, 10]. Recent reviews and position papers point to various topics that are not adequately met in current development and research into AT and dementia: for example, the benefits of end-user involvement in the design of AT, exploration of barriers to deployment and adoption, the need for high-quality research on usability and effectiveness of AT, and ethical considerations [7, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14].

The ReACT study (Rehabilitation in Alzheimer's disease using Cognitive support Technology) is based on the promising perspectives of using AT to support people with dementia in coping with the consequences of cognitive symptoms and thereby support self-management in everyday life [9, 15].

The first aim of the study was to design an app (the ReACT app) as an easily accessible AT, which can meet the heterogeneous needs of people with mild to moderate dementia in relation to self-management. The second objective was to develop and assess methods, which can reinforce deployment and adoption of this kind of AT. The third objective was to explore relevant outcome measures for capturing the possible benefits of using AT to support self-management of people with dementia.

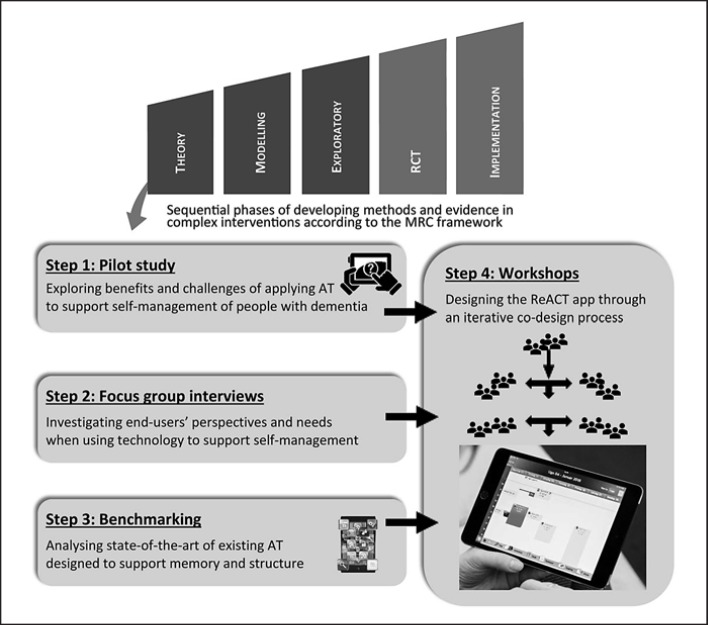

The ReACT study comprises a range of interacting components and its design is therefore based on the principles of the Medical Research Council framework for development and evaluation of complex interventions [16], as illustrated in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

The 4 steps of the theoretical phase of the ReACT study.

Methods

This paper describes the initial theoretical phase of the ReACT study, which led to the design of the ReACT app. The iterative process of designing the ReACT app comprised 4 steps, which are illustrated in Figure 1. They include an explorative pilot study, focus group interviews, a product benchmarking process, and the final codesign process. To provide a clear overview of this iterative stepwise process, the methods and results of these 4 steps are presented separately in this paper, and subsequently compiled and elaborated in the discussion.

The initial step, the explorative pilot study, was conducted in 2014, and the following 3 steps were conducted from January to June 2016.

Step 1: Explorative Pilot Study

A pilot study was conducted to explore the potential benefits and challenges of applying apps to support self-management of people with early-stage dementia.

The apps were provided on tablet computer (iPad), and they were introduced as part of a group-based self-management programme for people with early-stage Alzheimer's disease, where participants were introduced to various compensatory strategies, aids and tools that could support self-management in everyday life (unpublished data). It was not mandatory for participants to use the tablet and specific apps, but they were encouraged to try these solutions. At the time, no apps were available that were specifically designed for people with dementia, so other readily accessible off-the-shelf apps were selected for this pilot study. Selection criteria were that the app was in Danish, and that it was considered the best possible app solution to meet the participants' needs, preferences, and technology skills. Examples of apps were a calendar app, an Internet search app, an app for E-Mail communication, and a news app.

Step 1: Methods

Participants and Setting

Fourteen participants were recruited from the Memory Clinic at Danish Dementia Research Centre, where the pilot-study was also conducted. All participants had a clinical diagnosis of probable Alzheimer's disease, according to the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for Alzheimer's disease [17]. Based on clinical evaluation, they were assessed to be at an early stage of the disease.

The study ran as a group intervention with 2 consecutive groups of 7 participants. The participant's baseline characteristics are summarised in Table 1. One aim of the pilot was to explore if inexperienced users of touchscreen technology could also benefit from the intervention, and therefore it was not mandatory for participants to be previous user of a touchscreen device (smartphone or tablet). All participants were provided with an iPad during the intervention. The study was conducted by the first author (specialist in clinical neuropsychology with expertise in cognitive rehabilitation) and a psychology assistant.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics in step 1 (pilot study), step 2 (focus-group interviews), and step 4 (workshops)

| Participants1 | 1. Pilot study |

2. Focus group interviews |

4. Workshops |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PwD | FCG | PwD | FCG | PCG | PwD | FCG | PCG | |

| Number | 11 | 11 | 13 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Gender (male/female) | 5/6 | 6/5 | 7/6 | 1/1 | 1/5 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 0/4 |

| Age, years, mean (SD, range) | 66.3 (9.7, 53–82) | 61.5 (11.6, 41–86) | 60 (4.2, 57–63) | 49 (8.67, 40–64) | 72 (5.7, 65–78) | 71 (2.5, 68–73) | ||

| Diagnosis,n2 | AD: 11 | AD: 7 VaD: 1 Mixed: 1 Other: 4 | AD: 4 | |||||

| Time since diagnosis, years, mean (SD, range) | All <1.5 years | 2.4 (1.71, 1–6) | 1 (1.4, 0.5–1.5) | |||||

| Previous user of touchscreen technology (user/nonuser)3 | 5/6 | 10/3 | 2 | 6 | 4/0 | 4/0 | 4/0 | |

| Caregiver relation | Spouse: 9 Parent: 1 Son/daughter: 1 | Spouse: 1 Parent: 1 | Spouse: 4 | |||||

| Professional caregiver4 | Teacher: 3 OT: 1 CCW: 1 Nurse: 1 | OT: 2 CCW: 2 | ||||||

Participants: PwD, person with dementia; FCG, family caregiver; PCG, professional caregiver.

Diagnosis: AD, Alzheimer's disease; VaD, vascular dementia; Mixed, mixed AD and VaD.

Previous user of touchscreen technology: Tablet computer and/or smartphone.

Professional caregiver: Teacher (adult education), OT, occupational therapist; CCW, community care worker.

Procedure

The programme comprised 1 weekly 2-h session for a period of 10 weeks. Prior to the group programme, the participant and a family caregiver came to an individual session with staff conducting the intervention to discuss and specify the participants' needs and preferences in relation to self-management and compensatory means. During the group intervention, the compensatory strategies and tools, including the apps, were gradually introduced, practiced, and adapted to meet the user's individual needs and preferences.

Data Collection

The intervention was evaluated through individual semi-structured interviews with the participants and caregivers separately at the end of the programme. The interviews were based on 2 rather open-ended questions addressing the overall experience of participating in the programme and the use of touchscreen technology and apps to support self-management. Data from these interviews were collected by note-taking.

Three participants were excluded from the data set; 1 participant dropped out during the intervention after 3 sessions, she expressed discomfort with the group-based intervention, and 2 participants were absent at the time of post-intervention evaluations.

Data Analysis

Results from the interviews were coded by hand and processed and interpreted according to the principles of the general inductive approach [18]. The data analysis was conducted by the first author. To target the aim of this paper, only the results related to the use of technology are included.

Step 1: Results

Both participants and their caregivers reported benefits of using apps to support cognitive functions and self-management. A calendar app was used by 5 participants, and in these cases, all participants and caregivers pointed out advantages of using an electronic calendar compared to a paper version, for example, the use of notifications and the possibility for caregivers to support the use of the web-based calendar by having access to it from their own device. An E-Mail app was used by 7 participants, and they all reported that using an E-Mail app on a touchscreen device was a more accessible and convenient way to communicate by e-mail, compared to using a computer. Caregivers supported this observation. Three of the participants specifically reported that they felt more included in technology-based communication with friends and family after being introduced to the E-Mail app. Nine of the participants used an app for Internet search and they all mentioned that this gave them the advantages of a more effortless and independent access to information, compared to the often troublesome use of a computer.

However, the use of technology also presented obstacles. All participants expressed frustration with the need to set up and maintain software, for example, updating apps. It was generally perceived as difficult, and in many cases, impossible to accomplish for the person with dementia, even for participants who were experienced users of touch-screen technology. Moreover, all participants and caregivers requested apps that were tailor-made to the needs of people with dementia. They generally did not find the off-the-shelf apps sufficiently adaptable, well designed, or reliable.

Step 2: Focus Group Interviews

In the second step, people with dementia, family caregivers, and professional caregivers participated in focus group interviews. Adding to the results of step 1, the aim of the second step was to conduct an in-depth investigation of needs and wishes regarding the use of technology to support and enhance self-management of people with dementia.

Step 2: Methods

Participants and Setting

To include a broad range of perspectives, participants were recruited through purposive sampling. Interviews were conducted at 2 different established group settings for community-dwelling people with dementia: a meeting center and an adult education center offering tailor-made activities for people with dementia. To recruit participants, written information was handed out by staff to people attending activities at the settings. Those who showed interest were invited to participate in the interviews. People with dementia and staff participated at both settings, and at the meeting center family caregivers were also present. All participants clearly indicated that they were comfortable with giving their opinion in a joint group. Prior experience with technology was not mandatory to join the interviews. A total of 13 people with dementia, 2 family caregivers, and 6 professional caregivers participated in the interviews. Characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1.

Procedure

The focus group interviews were facilitated by the first author. To embrace all participants' experiences and views in the most flexible manner, interview questions were prepared as rather general questions addressing: positive experiences with technology, challenges in relation to technology, and wishes for future technology. It was specified that the focus of the interview was the use of technology to support self-management. To guide the interviews, and to support the participants' attention and memory, the interview questions were presented on posters. The questions were addressed in a flexible manner during the interviews to adapt to the pace and atmosphere of the specific group. The length of the focus group sessions varied between 1 and 2 h and were audio recorded in full agreement with all participants.

Data Analysis

Recordings from the focus group interviews were transcribed verbatim, and the data were subsequently processed and summarized in emerging themes, based on the principles of the Constant Comparison Analysis [19]. Analysis and coding were done by hand by the first author, and the themes, subthemes, and related quotes were subsequently translated into English to be included in this publication.

Step 2: Results

The themes that emerged in the focus group interviews covered a wide range of perspectives on the use of technology when living with dementia. For an overview of these themes and subthemes, see Table 2. These themes serve as headlines of the results and related quotes below and it is indicated whether a person with dementia (P) family caregiver (C) or staff (S) is quoted.

Table 2.

Emerging themes and subthemes in the focus group interviews

| Emerging themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Individual approaches to the use of technology | Common use of technology as an integrated part of modern life Preference for nontechnological solutions |

| Technology's influence on self-management | Positive influence on self-management Reduced access to society caused by the mandatory use of technology Feeling of inadequacy caused by technology use Stigmatizing caused by technology tailor-made for people with special needs |

| Special needs when using technology | People with dementia's need for education and support when using technology Caregivers' needs for education on how to support the use of technology Needs caused by cognitive symptoms |

| Special features of technology | Individualized and adaptable technology Reliable and efficient technology |

| Perspectives and wishes for future technology | Holistic solutions that provide user-friendly technology Features that can ease the use of technology and support cognition |

| Ethical and human right issues | Privacy Equal rights and access to technology |

Individual Approaches to the Use of Technology

Various approaches to the use of technology were discussed, underlining the broad range of individual preferences and needs. Both the common need and wish to use technology as an integrated part of modern life and the opposite, a preference for nontechnological solutions, was discussed.

P: “I try to use technology in the same as I have always done, it is necessary in so many ways nowadays.” (The participant explains that it is necessary to use technology for example to communicate with public authorities and to access e-banking.)

P: “With a paper diary it is easier to get an overview – you can sort of see everything at the same time … whereas with technology … you have to shut down and open up (programmes and apps) ... and you forget what you were doing.”

Technology's Influence on Self-Management

Participants gave examples of how technology can positively influence coping and self-management when living with dementia:

P: “I often forget to take my pills in the evening. Or I did … now I set an alarm in my phone…it reminds me.”

P: “You can put the appointment in (the calendar) … then you can always find it. Those calendars are quite smart.”

There were also examples of how a mandatory use of technology can limit access to society and services, and how specific technology features can obstruct access. For instance, the use of access codes seemed generally frustrating:

P: “You have access codes for everything ... even if I just want to look at special offers at the supermarket website … it's a nightmare. And then if you forget the code … you can ask for a new password, but you then have to remember your username, and if you can't you're lost.”

The growing demand to use web-based solutions to access services was also part of these discussions:

P: “My sister tells me that I should order my medicine through the web-site instead of calling (the doctor's secretary) and being on hold for ages. But I can't, and I'm just not able to learn how to do it.”

Some participants explained how these experiences often led to the feeling of inadequacy and incompetence when using technology:

P: “I get so frustrated … I cannot learn how to do it … I have tried, but it just goes into a muddle.”

P: “… then I tell my brain to slow down and not get too confused…but it doesn't understand … and it just gets worse. Then I turn it against myself ... and I withdraw.”

Some also gave examples of how technology tailor-made for people with cognitive disability had features that made them feel stigmatized:

P: “I was so happy when I found out how to turn off the sound on my GPS … for a long time the whole village could hear when I came riding on my bike…arguing with that nagging woman.” (Referring to the device voice).

C: (Talking about using cognitive training games on a touch-screen computer, participants describe them as oversimplified and childish) “ … there is a need for some (games) that are relevant for adults.”

Special Needs when using Technology

Education and support when using technology was one of the special needs of people with dementia that was highlighted during the discussions:

P: “It would be nice to have somewhere to go when things don't work, some person you could go to.”

P: “I have a son who can fix these things, he can sort things, so I cannot fiddle with it and that makes me feel comfortable.”

P: “Then you know … your community support worker comes in 2 weeks, and she can help you, but that is not useful. There has to be someone who can help right now.”

Also, family caregivers put forward their needs for education on how to assist and support the use of technology:

C: “… it is important that you know what to do … when you are so close (to the person with dementia) it can be difficult … So, I would find it useful to have someone explain exactly how to do it.”

The special needs of people with dementia caused by cognitive symptoms were stated as an essential issue to address if technology should be usable.

P: “We need something that isn't too confusing, things that are manageable.”

P: “It is important … to maintain your identity … that you have a calendar which you can manage.”

Special Features of Technology

The request for individualized and adaptable technology was highlighted when talking about designing technology for people with dementia:

P: “I think a good calendar is a calendar which can be set-up to be exactly how you want it.”

S: “The possibility to choose solutions … that is what's important.”

The need for reliable and efficient technology was also stressed:

P: “I love my GPS, but it is terrible when it crashes … it is so important that it is reliable.”

P: “It has to be working from day one and it must be flawless … I know it's a high demand.”

Perspectives and Wishes for Future Technology

Participants put forward specific ideas and wishes for future technology. Among these were various examples stressing the wish for more user-friendly technology. One example of user-friendly technology was to have holistic solutions that could combine multiple functionalities. It was also suggested that integration of various functionalities between apps could relieve the troublesome process of transferring information, for example, when looking up a contact person's address in a contact app and having to manually add this to an appointment in a calendar app, it was suggested that technology could provide a smarter solution. More specific ideas were also put forward. One example was the use of photos as a supplement to text and thereby support memory and communication. It was also suggested that integrating voice recognition could relieve users of typing text. Another idea was that technology could provide alternative ways to indicate time of the day that would be easier to understand for a person with dementia, for example, monitoring time of the day on a line.

Ethical and Human Right Issues

Ethics and human right issues were also discussed. Privacy was a main subject, and the wish for privacy was discussed in contrast to exposing private matters, for instance in situations where they needed assistance and support from professionals to use technology. This dilemma was considered unavoidable, but the participants in general relied on the ethics and confidentiality of professionals.

P: “… we have this disease, and we need help … that's the way it is, so we have to give permission that someone comes and helps us with our calendar … and the people who come and do this … well, they are bound to maintain privacy.”

Issues on equal rights and access to technology were also discussed, and participants argued for the request to give technology the same status as other assistive devices when it comes to accessibility and support:

P: “If you have a wheelchair and it breaks down you get a new one (assistive devices are provided by the public sector in Denmark). When my GPS broke down I could not get a new one. So, I was lost, and I could just sit back home and do nothing for 3 weeks.”

Step 3: Benchmarking Existing AT Solutions

The third step was a product benchmarking process, which was conducted to gain an overview and analyze state-of-the art of existing solutions. Benchmarking is a multifaceted technique widely used in many organizational and business contexts to support innovation and enhance operational efficiency and effectiveness [20]. In this study, the benchmarking process was conducted to identify potential advantages and gaps of current solutions to further qualify the app design process.

In steps 1 and 2, end-users had emphasized the need to support memory as essential to self-management, and consequently products promoted to meet such needs were the focus of this benchmarking process.

Step 3: Methods

Procedure

An explorative search was conducted in January 2016 to identify apps and other software products that were accessible in Denmark and therefore could be reviewed. A search was conducted in Apple's App Store [21] and Google Play [22], and a Danish online catalogue of assistive technologies was searched [23] to explore other software solutions that were not designed as apps.

The following search terms were used independently: Dementia, memory, and calendar. Both English terms and the equivalent Danish terms were used in both app stores. Only products that were promoted to support memory and mentioned people with dementia as potential users were included. Products that were not within this scope, for example, products targeting cognitive training, testing of cognitive functions, information about dementia, or support for caregivers, were excluded. The benchmarking process was not intended to be a systematic review, but an overview of features and designs in current solutions promoted for people with dementia. However, a Google Scholar search was conducted to explore if any of the identified solutions were associated with any research activity.

Data Analysis

The solutions that were identified were analyzed based on information that was provided by developers in the app stores and the online catalogue at the current time. If available, websites describing the solutions were also accessed, to collect additional information. Due to copyright issues and later modification of products and product information, it is not possible to include specific references.

Step 3: Results

The search in app stores and the online catalogues of assistive technologies did not identify any solutions that were specifically designed for people with dementia. However, we did identify 3 solutions that were promoted as applicable for people with dementia, but not exclusively. They were also promoted as suitable for other groups of people with cognitive symptoms (e.g., caused by ADHD, autism, or brain injury). These were an app and 2 series of tailor-made software packages that could be applied on a small variety of smart phones and tablets.

A calendar was a key functionality in these 3 solutions, and other features were, for instance, reminders, individualized activity guiding, and picture messages. The design of these products was in general characterized by simple layouts, use of symbols, pictograms, photos, and a few contrasting colors. There was no documentation available to specify if and how the solutions were designed, tested, or validated in relation to people with dementia or other potential end-users, and the Google Scholar search did not identify any scientific publications in relation to the solutions.

Step 4: The Iterative User-Involving Design Process

In the fourth and final step, the ReACT app was designed based on an iterative user-involving design process. As illustrated in Figure 1, the perspectives and ideas for functionalities and design were based on the results of the previous 3 steps, and in this fourth step, the functionalities and the layout of the app were discussed and gradually developed during the workshops.

The app was produced in a public–private innovation partnership-involving professionals with expertise on dementia from the public partner and experts on app development from the private partner.

To reach a manageable diversity in the design scope, it was decided to focus on the needs and perspectives of community-dwelling people with early-stage Alzheimer's disease as the primary target group for the app. Consequently, people matching this profile and their family caregivers were recruited to participate in the design process. Also, the professional caregivers participating in the process were instructed to base their views and advice on this subgroup.

Step 4: Methods

Participants

Four dyads of people with early-stage Alzheimer's disease and their closest relative were recruited from the memory clinic at Danish Dementia Research Centre, and 4 professional caregivers were recruited from the research center's network of dementia specialists. To have the richest possible dialogue and feedback during the design process, it was essential for all participants to be familiar with the use of touch screen technology. The characteristics of participants are included in Table 1.

Procedure

The 5 workshops that were conducted during the iterative design process are illustrated in Figure 1.

The first workshop only involved the professionals. The aim of this workshop was to initiate the design process by identifying user scenarios, user journeys, flows, and scopes and limits of the app. To introduce the perspectives and needs of end-users, and to the begin narrowing down the scope and features of the ReACT app, the workshop was initiated with a condensed overview of the results from steps 1, 2, and 3. Material for the successive workshops was based on the results of this workshop.

This first workshop was followed by 2 sets of parallel workshops with separate groups of end-users: 1 group included people with early-stage Alzheimer's disease and family caregivers and the other group included professionals. The workshops were conducted with separate groups to adapt the setting and discussion to the needs of the participants. The workshops with professionals were more extensive and included discussions on complex design and technical issues that were difficult to access for nonspecialists. The first set of parallel workshops focused on user-flows and ideas for design. In the second set of parallel workshops, the design of the app was discussed and validated.

The workshops were conducted at the Danish Dementia Research Centre and were facilitated by the first author and a coworker (expert on communication and technology).

Data from the workshops were collected as notes and illustrations on flip charts. The workshops were also audio recorded, but recordings were not transcribed, they were used to support note-taking if necessary.

Step 4: Results

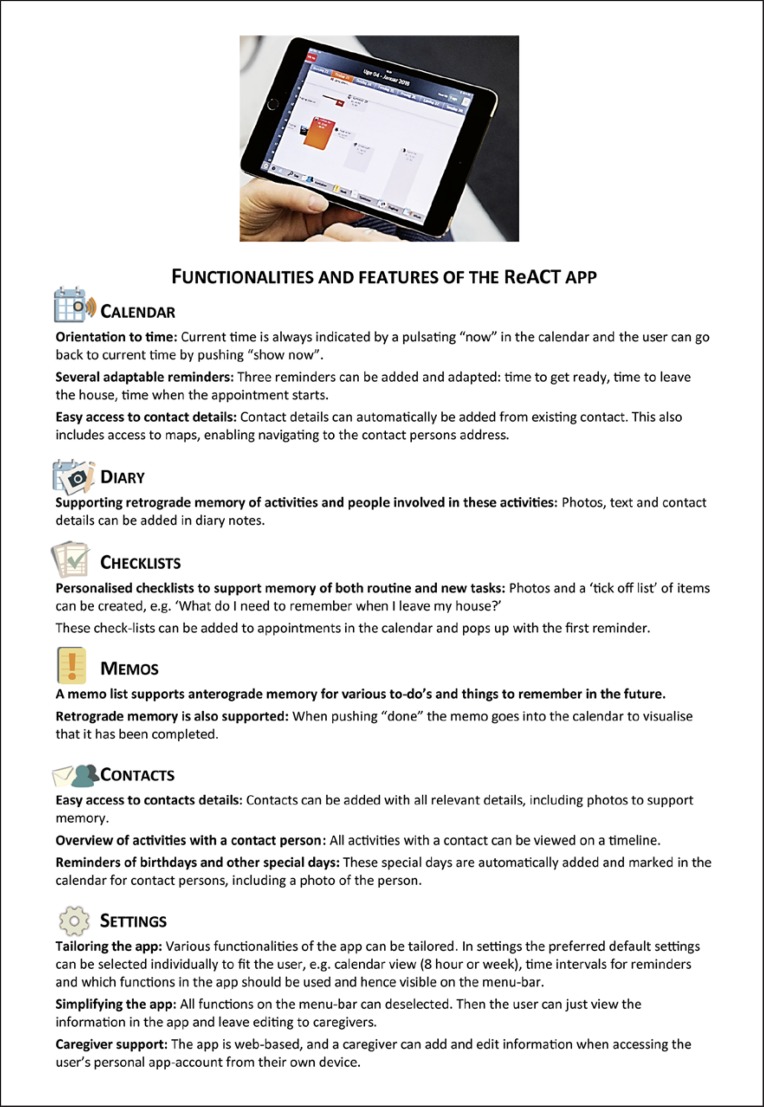

The result of the iterative innovation process is the ReACT app, and the design and functionalities of the app are illustrated in Figure 2. The app is a holistic solution with a calendar as a main framework for the multiple integrated and interacting functionalities: diary, checklists, and contacts. As described in Figure 2 the various special features of the app are tailor-made to meet the needs of end-users that were pointed out by participants during the various steps of this study. Moreover, the app can be adapted to individual preferences, needs, and skills; this is done by editing various features in the “Settings” menu. This includes the possibility to select individualized default settings and selecting/deselecting the various functionalities of the app. The app works in overlays and animations were added to support memory, structure, orientation to current time, and the flow within and between functionalities.

Fig. 2.

Functionalities and features of the ReACT app.

The ReACT app is a native cloud-based app that enables caregivers to have parallel access to the app, and both view, add and edit information, and thereby giving people with dementia access to support from caregivers when using the app.

Discussion

The ReACT app was designed to comply with the request for AT that genuinely reflects and meets the self-management needs of people with dementia.

The perspectives and needs of the end-users were essential throughout the 4 iterative steps presented in this paper, which led to the final design of the app: In the initial step, the explorative pilot study revealed the potential benefits and challenges of using apps to support self-management when living with early-stage dementias. In the second step, focus-group interviews provided varied perspectives on the use of technology to support self-management of people with dementia. In the third step, a product benchmarking process served to further qualify the design process. Finally, the results from these first 3 steps served as a basis for the fourth step, where the ReACT app was designed through an iterative process with direct user-involvement. The 4 steps are illustrated in Figure 1.

Results from the pilot study in step 1 and the focus group interviews in step 2 underlined the request for AT, for example, apps, tailor-made for people with dementia and this was supported by the results from the product benchmarking process in step 3, where very few existing solutions promoted as suitable for people with dementia were identified. These solutions were not specifically developed for people with dementia and no specified information was provided regarding end-user involvement in the design process and testing. This lack of user-involvement when designing and testing AT for people with dementia has been highlighted in several position papers and reviews, all advocating the strong need for user-involvement to promote applicability and acceptability of AT [9, 13, 24, 25].

The solutions that we identified in the benchmarking process were also promoted without any evidence for effectiveness and applicability for people with dementia, and this is in line with the observation of a general lack of evidence for the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of AT solutions for community-dwelling people with dementia [8, 9]. Designing and deploying AT solutions for people with dementia is a new and fast expanding field, and large investments are being made, but this is apparently based on very limited evidence, which is in striking contrast with the demand for evidence-based solutions when considering pharmacological and other nonpharmacological solutions for people with dementia [2].

The involvement of end-users in the ReACT study facilitated various decisions during the study. Initially, the decision to develop software technology for an off-the-shelf touchscreen device in the ReACT project was based on the positive results from both steps 1 and 2. Participants and caregivers in the explorative pilot study generally appreciated the accessibility and usability of the touchscreen devices and the apps. Accessibility and usability were also discussed as essential for initiating and maintaining use of technology in the focus-group interviews. This preference for touch-screen devices is in line with the results of other studies, emphasizing the intuitive interface, user-friendliness, adaptability, and multifunctional nature of such devices [26, 27].

The results from steps 1 and 2 also led to the selection of the specific touch-screen device used in the study. For practical reasons, it was necessary to build the ReACT app for one specific hardware device during the design and test phase. The selection of hardware device was not based on actual tests comparing different hardware solutions; however, the Apple tablet (iPad) was found user-friendly both by people with dementia and caregivers in step 1, and users who had no previous experience with tablet computers learned to use an iPad in this pilot study. This selection of device was also supported by the fact that iPads are the most commonly used tablets in Denmark [28]. Based on these findings, it was decided that the ReACT app should be built for iPads. The preference for iPads by people with dementia is also supported by other studies [27, 29], emphasizing the user-friendliness and intuitive interface of these specific devices. In future dissemination of the app, it should of course be provided for a variety of touchscreen hardware, to meet the individual preferences of end-users.

Results from both the pilot-study and focus group interviews in steps 1 and 2 indicated the potential benefits of using apps to support self-management when living with dementia. More specifically, the need to support both prospective and retrospective memory in daily living was put forward as essential to self-management by both people with dementia and caregivers. This is in line with other studies documenting that people with dementia experience unmet needs in relation to memory support [30, 31], and support of memory and other cognitive functions have been described as essential in relation to the wish for self-management [29]. The potential of using AT to support people with dementia when coping with the consequences of cognitive symptoms, and thereby support self-management in everyday life, has also been discussed and confirmed by others [9, 15, 29].

Based on the results from our pilot study and focus group interviews a calendar seemed to be the essential part of the solution that most end-users requested. The products that were identified in the benchmarking process were also based on various approaches to designing a calendar solution. In addition to a calendar system, the need for a holistic solution was also pointed out in both steps 1 and 2. In the focus-group interview, it was discussed how features of various programmes/apps could be integrated and thereby relieve the troublesome process of manually transferring information, which sometimes led to abandonment of technology. It was also suggested that solutions which could integrate various features such as personal photos and voice recognition were useful to support memory and other cognitive functions. The advantages of designing holistic solutions for people with dementia have also been emphasized in other studies [32, 33]. As a result, the ReACT app was designed as a holistic solution, using a calendar as a main framework and integrating a variety of functionalities that were emphasized by end-users as essential to support self-management in their everyday life. This led to the functionalities, and interaction between functionalities, that are described in Figure 2.

However, the effects of using electronic memory aids for people with dementia have until now been sparsely explored by a small number of studies with limited generalizability [15, 34]. Further studies in the ReACT project will address the usability and effect of applying this kind of AT to people with dementia.

Our initial explorative pilot study revealed that apps that are tailor-made and adaptable to fit individual needs and preferences for people with dementia are requested. The debates in the focus-group interviews also underlined the broad range of individual preferences and needs that should be addressed when designing AT for people with dementia. The adaptability of AT to meet the heterogeneousness of people living with dementia has also been requested by others [26, 35, 36]. Ideally, the adaptability should comply both with the varied needs and individual preferences of people with dementia and with the change in these individual needs caused by the nature of progressive dementia diseases. To meet these requirements, the ReACT app was made adaptable by enabling individualized default settings in various features of the app and by the option to deactivate functions, as described in Figure 2.

Results from both steps 1 and 2 underlined the general need for education and support of people with dementia when using technology. In the pilot study, participants generally found setting up and updating software unmanageable, and requested support for this, and the need for continued education and support was also discussed in the focus-group interviews. These need for support and education have also been discussed by others [9, 37, 38]. To meet these needs, the ReACT app was designed as a web-based solution, which allows access to a user's personal app account from various devices, and this can facilitate caregiver support, even at a distance. Furthermore, the needs for education and support will be addressed in the subsequent studies of the ReACT project, which will address the equally important issues of deployment and adoption of AT to people with dementia [13, 39].

The design and methods of this study caused some limitations. One limitation was that participants in the sub-studies were recruited through convenience sampling. The intention was to include a wide variety of people with early-stage dementia from various settings, but this resulted in a neglect of people with dementia who do not take active part in regular activities for people with dementia or are not in close contact with a memory clinic. Processing of data also implied potential limitations. Coding of data, checking of coding, analysis, and translation of interviews were conducted by only one researcher and this could have been added more rigor if additional researchers had been involved. Also, the splitting of workshops into 2 parallel groups in step 4 could be a potential limitation, since the benefits of directly combining views of end-users and professionals could be missed. The groups were split during the workshops to adapt the codesign process to the participants' needs, for example, spare the end-users the more extensive discussions on complex design and technical issues. The ReACT study was not designed to be a participatory study, but we found it highly beneficial to have end-users participating as codesigners in the iterative design phase [24]. We find that general principles of user-centered system design [40] can be directly applied when designing AT for people with dementia and should be applied. This framework considers end-users at each stage of the design process and actively involves users throughout the entire development process and system lifecycle [40]. However, conducting research in relation to design and creation of technology such as apps does imply issues that are highly complex, and it can be challenging to modify and adapt all research issues to be adequately dementia friendly. Based on these considerations, we find that conducting genuine participatory research when designing AT for people with dementia does imply specific challenges that have to be addressed in future studies.

Conclusion

The ReACT app was designed to support the needs of people with dementia in relation to self-management. The app was designed through an extensive iterative user-involving process where we identified a request for a holistic and adaptable solution with main features supporting memory in daily living.

The usability and applicability of the app are promising, since the app functionalities and design are directly based on user needs and perspectives. However, the app will be tested by end-users in further studies of the ReACT project, to see if adaptions are needed. Further studies will also address the equally important request for methods to promote deployment and adoption of AT tailor-made for people with dementia.

Statement of Ethics

The study protocol was evaluated by the regional scientific ethical committees of The Capital Region of Denmark (protocol number H-15005558), where it was decided the study did not need approval, since it was not considered to be within the framework of biomedical research.

All participants received oral and written information about the overall study objectives and the details of the specific step they participated in. They all gave written informed consent.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The study presented in this paper did not receive external funding.

Author Contributions

The corresponding author was involved in all aspects of conceptualizing and designing the study, the acquisition of data, and the analysis and interpretation of data. All authors made substantial contributions to designing the study and were involved in writing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the cooperation and great engagement of all participants, family caregivers, and professionals involved in the various steps of the study. The study greatly benefited from collaboration with app development experts from the private partner BridgeIT Aps during the public–private innovation partnership in step 4. We are also grateful to our colleagues at Danish Dementia Research Centre, for their extensive support and involvement in the ReACT project, including Mette Tandrup Hansen, who participated in the facilitation of workshops and the design process in step 4.

Danish Dementia Research Centre is supported by the Danish Ministry of Health.

References

- 1.WHO Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025. 2017 [Cited 2018 Dec 3]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259615/?sequence=1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winblad B, Amouyel P, Andrieu S, Ballard C, Brayne C, Brodaty H, et al. Defeating Alzheimer's disease and other dementias: a priority for European science and society. Lancet Neurol. 2016 Apr;15((5)):455–532. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moniz-Cook E, Vernooij-Dassen M, Woods B, Orrell M, Interdem Network Psychosocial interventions in dementia care research: the INTERDEM manifesto. Aging Ment Health. 2011 Apr;15((3)):283–90. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.543665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olazarán J, Reisberg B, Clare L, Cruz I, Peña-Casanova J, Del Ser T, et al. Nonpharmacological therapies in Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review of efficacy. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;30((2)):161–78. doi: 10.1159/000316119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ADI Bibliography of References to National Plans. 2016 [Cited 2018 Dec 3] Available from: https://www.alz.co.uk/sites/default/files/pdfs/national-plans-bibliography-2016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Assistive Technology Industry Association 2018 [Cited 2018 Dec 3] Available from: http://www.atia.org/at-resources/what-is-at/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asghar I, Cang S, Yu H. Assistive technology for people with dementia: an overview and bibliometric study. Health Info Libr J. 2017 Mar;34((1)):5–19. doi: 10.1111/hir.12173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibson G, Newton L, Pritchard G, Finch T, Brittain K, Robinson L. The provision of assistive technology products and services for people with dementia in the United Kingdom. Dementia. 2016 Jul;15((4)):681–701. doi: 10.1177/1471301214532643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meiland F, Innes A, Mountain G, Robinson L, van der Roest H, García-Casal JA, et al. Technologies to support community-dwelling persons with dementia: a position paper on issues regarding development, usability, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, deployment, and ethics. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol. 2017 Jan;4((1)):e1. doi: 10.2196/rehab.6376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van der Roest HG, Wenborn J, Pastink C, Dröes RM, Orrell M. Assistive technology for memory support in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jun;6:CD009627. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009627.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett B, McDonald F, Beattie E, Carney T, Freckelton I, White B, et al. Assistive technologies for people with dementia: ethical considerations. Bull World Health Organ. 2017 Nov;95((11)):749–55. doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.187484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ienca M, Jotterand F, Elger B, Caon M, Pappagallo AS, Kressig RW, et al. Intelligent assistive technology for Alzheimer's disease and other dementias: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;56((4)):1301–40. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenigsberg PA, Aquino JP, Bérard A, Brémond F, Charras K, Dening T, et al. Assistive technologies to address capabilities of people with dementia: from research to practice. Dementia. 2017 Jan;•••:1471301217714093. doi: 10.1177/1471301217714093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zwijsen SA, Niemeijer AR, Hertogh CM. Ethics of using assistive technology in the care for community-dwelling elderly people: an overview of the literature. Aging Ment Health. 2011 May;15((4)):419–27. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.543662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King AC, Dwan C. Electronic memory aids for people with dementia experiencing prospective memory loss: A review of empirical studies. Dementia. 2017 Jan;•••:1471301217735180. doi: 10.1177/1471301217735180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M, Medical Research Council Guidance Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008 Sep;337:a1655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984 Jul;34((7)):939–44. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Eval Pract. 2006;27((2)):237–46. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leech NL, Onwuegbuzie AJ. An array of qualitative data analysis tools: a call for data analysis triangulation. Sch Psychol Q. 2007;22((4)):557–84. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yasin MM. The theory and practice of benchmarking: then and now. Benchmark Int J. 2002;9((3)):217–43. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Apple Itunes App store. [Cited 2016 June 1]. Available from: https://itunes.apple.com/dk/genre/ios/id36?mt=8.

- 22.Google Play Apps [Cited 2016 June 1]. Available from: https://play.google.com/store.

- 23.Denmark AT. [Cited 2016 June 1] Available from: https://hmi-basen.dk/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Span M, Hettinga M, Vernooij-Dassen M, Eefsting J, Smits C. Involving people with dementia in the development of supportive IT applications: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2013 Mar;12((2)):535–51. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Topo P. Technology studies to meet the needs of people with dementia and their caregivers: a literature review. J Appl Gerontol. 2009;28((1)):5–37. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joddrell P, Astell AJ. Studies involving people with dementia and touchscreen technology: a literature review. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol. 2016;3((2)) doi: 10.2196/rehab.5788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim FS, Wallace T, Luszcz MA, Reynolds KJ. Usability of tablet computers by people with early-stage dementia. Gerontology. 2013;59((2)):174–82. doi: 10.1159/000343986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World C. Nye danske data afslører: Her er de mest populære smartphones i Danmark. 2016 [Cited 2016 Dec 1] Available from: https://www.computerworld.dk/art/238637/nye-danske-data-afsloerer-her-er-de-mest-populaere-smartphones-i-danmark. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerkhof Y, Bergsma A, Graff M, Dröes R. Selecting apps for people with mild dementia: identifying user requirements for apps enabling meaningful activities and self-management. J Rehabil Assist Technol Eng. 2017;4:2055668317710593. doi: 10.1177/2055668317710593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miranda-Castillo C, Woods B, Orrell M. The needs of people with dementia living at home from user, caregiver and professional perspectives: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013 Feb;13((1)):43. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Roest HG, Meiland FJ, Comijs HC, Derksen E, Jansen AP, van Hout HP, et al. What do community-dwelling people with dementia need? A survey of those who are known to care and welfare services. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009 Oct;21((5)):949–65. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boman IL, Persson AC, Bartfai A. First steps in designing an all-in-one ICT-based device for persons with cognitive impairment: evaluation of the first mock-up. BMC Geriatr. 2016 Mar;16((1)):61. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0238-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meiland FJ, Hattink BJ, Overmars-Marx T, de Boer ME, Jedlitschka A, Ebben PW, et al. Participation of end users in the design of assistive technology for people with mild to severe cognitive problems; the European Rosetta project. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014 May;26((5)):769–79. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214000088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Imbeault H, Gagnon L, Pigot H, Giroux S, Marcotte N, Cribier-Delande P, et al. Impact of AP@LZ in the daily life of three persons with Alzheimer's disease: long-term use and further exploration of its effectiveness. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2018 Jul;28((5)):755–78. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2016.1172491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ancient C, Good A, Considering people living with dementia when designing interfaces . Design, User Experience, and Usability. In: Marcus A, editor. User Experience Design Practice DUXU 2014 Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Volume 8520. Cham: Springer; 2014. pp. pp. 113–23. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Egan KJ, Pot AM. Encouraging innovation for assistive health technologies in dementia: barriers, enablers and next steps to be taken. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016 Apr;17((4)):357–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dewar BK, Kapur N, Kopelman M. Do memory aids help everyday memory? A controlled trial of a Memory Aids Service. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2018 Jun;28((4)):614–32. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2016.1189342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kerkhof YJ, Graff MJ, Bergsma A, de Vocht HH, Dröes RM. Better self-management and meaningful activities thanks to tablets? Development of a person-centered program to support people with mild dementia and their carers through use of hand-held touch screen devices. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016 Nov;28((11)):1917–29. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216001071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Papoutsi C, Lynch J, Hughes G, A'Court C, et al. Beyond adoption: a new framework for theorizing and evaluating nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. J Med Internet Res. 2017 Nov;19((11)):e367. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gulliksen J, Göransson B, Boivie I, Blomkvist S, Persson J, Cajander Å. Key principles for user-centred systems design. Behav Inf Technol. 2003;22((6)):397–409. [Google Scholar]