Institutions should develop, implement, and monitor processes to ensure transparency and appropriate consent from patients for medical students performing pelvic examinations under anesthesia.

Abstract

The pelvic examination is a critical tool for the diagnosis of women's health conditions and remains an important skill necessary for students to master before becoming physicians. Recently, concerns regarding student involvement in pelvic examinations—specifically those performed while a woman is under anesthesia—have been raised in the scientific, professional, and lay literature. These concerns have led to calls to limit or halt the performance of pelvic examinations by students while a woman is under anesthesia. Although ensuring adequate informed consent for teaching pelvic examinations is a priority, we must not lose sight of the critical pedagogical value of teaching pelvic examination in familiarizing students with the female anatomy and instilling a physician workforce with confidence in pelvic examination skills. A compromise that addresses all of these values is possible. In this commentary, we review the educational and legal aspects of the pelvic examination under anesthesia, then provide strategies that individuals and institutions can consider to optimize processes regarding consent for pelvic examination under anesthesia.

The pelvic examination is a critical tool to aid in the diagnosis of women's health conditions and remains an important skill necessary for students to master before becoming physicians. Recently, concerns regarding student involvement in pelvic examinations—specifically those performed while a woman is under anesthesia—have been raised in the scientific, professional, and lay literature.1–4 Patients describe a pelvic examination under anesthesia without adequate consent as a violation; students describe the practice as shameful. These concerns have led to calls to limit or even halt the performance of pelvic examinations by students while a woman is under anesthesia.1–3 Patient safety, informed consent, and transparency are of paramount importance. Yet we must not lose sight of the pedagogical value of familiarizing students with the female anatomy and instilling a physician workforce with confidence in pelvic examination skills. A compromise that addresses all of these values is possible.

VALUE OF THE PELVIC EXAMINATION

Pelvic examination is an integral part of the evaluation of women presenting with many common conditions, including pelvic pain, abnormal bleeding, vaginal discharge, and sexual dysfunction.5 Pelvic examination—both in the office and while under anesthesia—is also a crucial component of preoperative evaluation for gynecologic procedures to ensure safe completion of the planned procedure.5 Therefore, pelvic examination skills are important for physicians across specialties and must continue to be taught and mastered during undergraduate medical education.

PELVIC EXAMINATION UNDER ANESTHESIA BY STUDENTS

Students often initially learn pelvic examination skills on simulation mannequins or on nonpatient volunteers, and then typically achieve proficiency with these skills on the family medicine and obstetrics and gynecology clerkships.6 In outpatient settings, women have the capacity to readily consent—or decline—student involvement in their care, including performing the pelvic examination. In the operating room, students may perform pelvic examinations while a woman is under anesthesia. In this setting, whether the woman fully understood and consented to a student’s involvement can be less clear, and the potential for harm arises. That potential harm may range from a student experiencing guilt or anxiety to the distrust that may develop in the operating room team if the nursing staff, for instance, feel that the patient is being violated, to a patient herself feeling violated, experiencing posttraumatic stress disorder, or losing trust in women's health care providers if she discovers such an examination was performed without her understanding or consent.4,7,8 Health care providers must recognize the importance of ensuring the safety of both our patients and our learners by providing transparency surrounding the pelvic examination under anesthesia.

Explicit consent for pelvic examination under anesthesia has been endorsed by medical professional societies for nearly a decade.9–12 Statements from professional societies and laws by states that address the issue of pelvic examination under anesthesia consistently note that the examination should not be performed when it is unrelated to the procedure being done (eg, an examination under anesthesia preceding a tonsillectomy). As well, each indicates that women should be aware whenever learners will be involved in their care and that women be permitted to decline student involvement without reprisal. Yet, controversy exists as to how consent for examination under anesthesia should be obtained, documented, and communicated to the health care team. Processes surrounding consent for pelvic examination under anesthesia vary between and within institutions (Carungo JA. Practicing pelvic examinations by medical students on women under anesthesia: why not ask first? [letter] Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:1479–80).11,13

Students should be made explicitly aware of institutional consent procedures related to examination under anesthesia.13 The consent process for examination under anesthesia typically occurs well in advance of the procedure, when the student is unlikely to be present. Many studies regarding examination under anesthesia—which have also informed the lay literature on this topic—rely on student impression as to whether consent was obtained rather than review of consent forms or discussion with consenting physicians or the patients themselves.8,14,15 Improving processes—and student awareness of the processes—related to examination under anesthesia will therefore serve to both reduce student stress regarding examination under anesthesia and improve our understanding of how often unconsented examination under anesthesia truly occurs.

LEGAL ASPECTS OF PELVIC EXAMINATION UNDER ANESTHESIA

Informed consent for medical interventions began as a legal requirement in the United States at the turn of the 20th century. Interestingly, the foundational consent case, Schloendorff v Society of New York Hospital (1914), was a gynecologic one. This and subsequent cases established that, if a clinician touches a patient in an “unconsented and offensive” fashion, the clinician may be held liable in a court of law. Later case law refined the conceptualization of clinical consent to mandate consent that is actually “informed.” Specifically, patients consenting to a procedure must 1) have adequate capacity to understand the situation; 2) have enough information regarding risks, benefits, and alternatives to make a good decision for themselves; and 3) be free from coercion. Case law does not anticipate that clinicians simply dump all possible information on patients—instead, they have an affirmative obligation to use discretion to present the most important information to the patient. This discretion does not, however, protect clinicians from disclosing information they worry might dissuade a patient from making a choice they recommend.

Starting in 2004, states began passing laws mandating certain standards for pelvic examination under anesthesia. As of 2019, seven states (California, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Oregon, Utah, and Virginia) have such laws, and others are considering them. However, these state laws focus on prohibiting the obvious affront to a patient's autonomy of receiving an examination under anesthesia when a pelvic examination is otherwise outside the scope of care for the procedure or examination they are undergoing. For example, the California law says that a student, “may not perform a pelvic examination on an anesthetized or unconscious female patient unless the patient gave informed consent to the pelvic examination OR the performance of a pelvic examination is within the scope of care for the surgical procedure or diagnostic examination…” (Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code §2281, 2017). Unlike other state informed consent laws (eg, genetic testing) that lay out in detail disclosures necessary and type of informed consent,16 these state laws do not offer guidance on how informed consent for examination under anesthesia should be obtained (eg, an affirmative opt-in process vs standard disclosure language on an informed consent form) or other best practice procedures to protect patients' dignity.

PROCESSES REGARDING CONSENT FOR PELVIC EXAMINATION BY STUDENTS

Nonanesthetized Pelvic Examinations

Nonanesthetized patients are able to provide verbal consent for student participation in their care, including pelvic examination. Typical practices for nonanesthetized pelvic examinations include a verbal exchange between a medical assistant and the patient as to her willingness to involve a medical student in her care, often followed by a second verbal exchange between the clinician and the patient before the examination is done.6

To ensure transparency and protect both patients and learners, institutions and clinicians may consider standardized documentation of patient assent. Approaches for documentation of patient assent to student participation in nonanesthetized pelvic examination may include:

Adding checkboxes to medical record templates.

Adding a line within progress notes in electronic medical record templates.

A sticker—similar to a “time out” sticker—affixed to paper medical records indicating that the patient agreed to pelvic examination by a student.

Pelvic Examination Under Anesthesia

Once under anesthesia, a woman is no longer able to consent to what happens to her body. Surgeons recognize this loss of capacity by preemptively discussing intraoperative decisions such as whether a patient would accept blood transfusion. Although patients vary in the amount of information they need to make an informed decision regarding their procedure, generally patients are to be apprised of risks, benefits, and alternatives to any procedure. Most women report that they would want to know if a learner would be performing a pelvic examination while they are under anesthesia (Bibby J, Boyd N, Redman C, Luesley D. Consent for vaginal examination by students on anaesthetized patients [letter]. Lancet 1988;2:1150),17 although it is not legally clear whether that potential dignitary harm should be considered an actual “risk” of the overall procedure the woman is about to undergo.

Processes for obtaining and documenting informed consent should be compliant with state and local laws and vetted by institutions' legal departments. Institutions are responsible for disseminating and training clinicians and staff on these processes, as well as monitoring for compliance. Ensuring consent for examination under anesthesia should be the responsibility of the clinician obtaining consent for the procedure and should be initiated before the day of the procedure for nonemergent procedures.13 Consent for examination under anesthesia should not be the sole responsibility of the student.13

Examples of standard processes to ensure that consent for examination under anesthesia is obtained and documented include:

Supplemental consents for student examination under anesthesia (similar to refusal of blood products consent forms).

Stickers on the main consent form attesting that discussion of examination under anesthesia was done and consent obtained (similar to “time out” documentation stickers).

Including the term “exam under anesthesia” preceding the surgical procedure on consent forms (eg, “exam under anesthesia, laparoscopic salpingectomy” on the procedure line of a consent form rather than simply “laparoscopic salpingectomy”) to complement language already common to surgical consent forms regarding student involvement.

Examination under anesthesia within the surgical consent form.

Inclusion of an item on preinduction checklists confirming whether the patient consented to examination under anesthesia by learners.

STRATEGIES TO IMPROVE STUDENT SAFETY AND WELL-BEING REGARDING EXAMINATION UNDER ANESTHESIA

In addition to the issues of patient safety and dignity associated with examination under anesthesia, it is medical students who have initiated the call for improved transparency regarding examination under anesthesia.7,8,14,15 In 2012, then-medical student Barnes7 published a widely circulated commentary in which he described the guilt he experienced after performing examination under anesthesia during his obstetrics and gynecology clerkship. In the years since, much of the research surrounding examination under anesthesia has used students' perceptions of the consent process as the means to determine whether consent had been obtained.8,14,15 Regardless of whether this is a valid surrogate, students' safety and well-being should be another consideration in efforts to improve transparency surrounding examination under anesthesia. A student unaware of the consent process specifically for examination under anesthesia may experience distress unnecessarily when asked to perform examination under anesthesia in the operating room. Improving the processes surrounding obtaining, documenting, and ensuring consent for examination under anesthesia will not only benefit the patient–provider relationship, but will also reassure our students and protect them from unnecessary psychological harm. Additionally, this serves as an opportunity to highlight the values of respect for persons, shared decision-making, and the consent process itself that we aspire to instill in physicians-in-training.14

The Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics has long recognized the importance of the consent process for pelvic examination under anesthesia by students, yet also acknowledges the renewed attention directed to this issue. In March 2019, the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics released a statement on teaching pelvic examinations to medical students, recommending that students perform a pelvic examination only when the patient provides explicit consent and recognizes that the student is part of their care team, when the examination is clinically relevant (eg, not done during a tonsillectomy), and when an educator directly supervises the examination.18

Organizations should prioritize patient autonomy and safety in policies regarding examination under anesthesia; however, improving student awareness of these patient protections should also be emphasized. Strategies to inform and support our learners in examination under anesthesia include:

Sharing the organizational approach to examination under anesthesia at clerkship orientations.

Preinduction checklists that include examination under anesthesia by learners (yes or no) as part of surgical protocols.

Supervision of students during examination under anesthesia, including confirmation of findings, describing rationale for examination under anesthesia before the planned procedure, and how examination under anesthesia informs the planned procedure.

CONCLUSION

As clinicians, obstetrician–gynecologists (ob-gyns) are entrusted to preserve the health and dignity of our patients, and this remains our utmost priority. As medical educators, we must balance our obligation to develop the next generation of physicians with women's freedom to decide from whom they receive treatment and what aspects of their care are performed by learners. It is also our obligation to ensure that our learners do not experience shame, guilt, or anxiety about their involvement in women's health care. When students witness transparent communication processes regarding consent for examination under anesthesia by students, we model the values of respect, autonomy, and shared decision-making that we strive to imbue within medical education.

Ob-gyns must go above and beyond in our efforts to preserve the trust that is central to our relationships with individual patients and with society at large. Institutions should develop, implement, and monitor processes to ensure transparency regarding pelvic examinations under anesthesia. Physicians should support and comply with these processes in our interactions with patients and with learners. The trust of our patients and the safety of our learners depend on it.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure Kayte Spector-Bagdady reports receiving funds from Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center; University of Central Florida, Board of Trustees. Meg O'Reilly disclosed that she is am a current board member of the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO), a past OBGYN Clerkship Director at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU), current director of the Reproductive Health Block at OHSU where pelvic exam skills are taught to medical students, and current Associate OBGYN Residency Program Director at OHSU. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal's requirements for authorship.

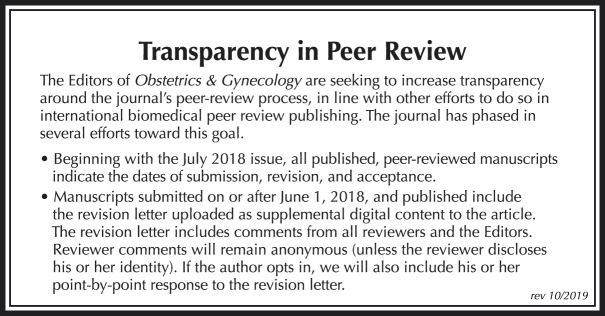

Peer reviews and author correspondence are available at http://links.lww.com/AOG/B608.

Figure.

No available caption

REFERENCES

- 1.Friesen P. Educational pelvic exams on anesthetized women: why consent matters. Bioethics 2018;32:298–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adashi EY. JAMA forum: teaching pelvic examination under anesthesia without patient consent. Available at: https://newsatjama.jama.com/2019/01/16/jama-forum-teaching-pelvic-examination-under-anesthesia-without-patient-consent/. Retrieved March 16, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Kasprak A. Is performing pelvic exams on unconscious women without informed consent legal? Available at: https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/pelvic-exams-informed-consent/. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- 4.Sullivan L. This American life: while you were out. Available at: https://www.thisamericanlife.org/661/but-thats-what-happened/act-two-3. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- 5.The utility of and indications for routine pelvic exam. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 754. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2018;132:e174–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van den Einden LC, te Kolste MG, Lagro-Janssen AL, Dukel L. Medical students' perceptions of the physician's role in not allowing them to perform gynecologic examinations. Acad Med 2014;89:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes SS. Practicing pelvic examinations on women under anesthesia: why not ask first? Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:941–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coldicott Y, Pope C, Roberts C. The ethics of intimate examinations—teaching tomorrow's doctors. BMJ 2003;326:97–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Professional responsibilities in obstetric-gynecologic medical education and training. Committee Opinion No. 500. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:400–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Medical Association. Code of medical ethics 9.2.1. Medical student involvement in patient care. Available at: https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/medical-student-involvement-patient-care. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- 11.Weiner S. What “informed consent” really means. Available at: https://news.aamc.org/patient-care/article/what-informed-consent-really-means/. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- 12.Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. Obtaining valid consent (clinical governance advice no. 6). Available at: https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/clinical-governance-advice-6/. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- 13.York-Best CM, Ecker JL. Pelvic examinations under anesthesia. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:741–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ubel PA, Jepson C, Silver-Isenstadt A. Don't ask, don't tell: a change in medical student attitudes after obstetrics/gynecology clerkships toward seeking consent for pelvic examinations on an anesthetized patient. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;188:575–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schniederjan S, Donovan GK. Ethics versus education: pelvic exams on anesthetized women. J Okla State Med Assoc 2005;98:386–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spector-Bagdady K, Prince AER, Yu JH, Appelbaum PS. Analysis of state laws on informed consent for clinical genetic testing in the era of genomic sequencing. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2018;178:81–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wainberg S, Wrigley H, Fair J, Ross S. Teaching pelvic examinations under anesthesia: what do women think? J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2010;32:539–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics. APGO releases statement on teaching pelvic exams to medical students. Available at: https://www.apgo.org/teaching-pelvic-exams-to-med-students. Retrieved July 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]