To the Editor:

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic, progressive, fibrosing lung disorder characterized by an unavoidable decline in pulmonary function and poor clinical outcomes. Despite significant efforts in basic and translational research over the past two decades, many aspects of the pathobiology of IPF remain elusive. The recent introduction of two effective agents for the treatment of the disease has significantly changed the clinical management of patients with IPF; however, the behavior of the disease and response to therapy are highly variable among patients. The individuation of new therapeutic targets and the validation of diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic biomarkers are widely recognized as urgent clinical needs (1).

In a recent study published in the Journal, Allden and coworkers elegantly demonstrated by means of a modern flow-cytometry approach that in IPF airways there is a distinct subset of alveolar macrophages (AMs) that downregulate the expression of the surface transferrin receptor CD71 and are phenotypically distinct with regard to their expression of profibrotic genes and impaired ability to take up transferrin in vitro (2). This subset of AMs was not significantly present in any of the healthy subjects tested in the study as the control population, and interestingly, its presence was correlated with worse clinical outcomes for patients.

In recent years, our group has proposed disruption of lung iron homeostasis as a possible key mechanism in IPF pathogenesis and progression. We demonstrated an increased iron burden in the IPF lung, both in the alveolar epithelial lining fluid and in AMs (3). Furthermore, we demonstrated that AMs produce an increased amount of reactive oxygen species via an iron-dependent mechanism (4) and display at the transcriptomic level a proinflammatory, prorepair, and proangiogenic activation pattern likely induced by iron accumulation (5).

With that as a background, we learned with great interest the results reported by Allden and coworkers, which again put iron metabolism under the spotlight in the pathobiology of IPF. In particular, the presence of an AM population lacking one of the fundamental mechanisms of intracellular iron uptake is intriguing and appears to be, at least in part, in line with our previous results. However, we believe that it would be of great interest to understand whether the presence of CD71− AMs represents a unique characteristic of the IPF lung or if they can also be detected in other chronic degenerative lung diseases. To address this issue, we performed a retrospective flow-cytometry analysis on BAL cell samples that were collected during our previous studies on iron metabolism and pulmonary fibrosis (4, 5). In particular, BAL cell samples from 21 patients with IPF and 18 patients without IPF (six with hypersensitivity pneumonitis, six with connective tissue disease–interstitial lung disease [ILD], three with nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, two with sarcoidosis, and one with Churg-Strauss syndrome) were tested for a panel of cell-surface markers that included CD45, CD11c, and CD71.

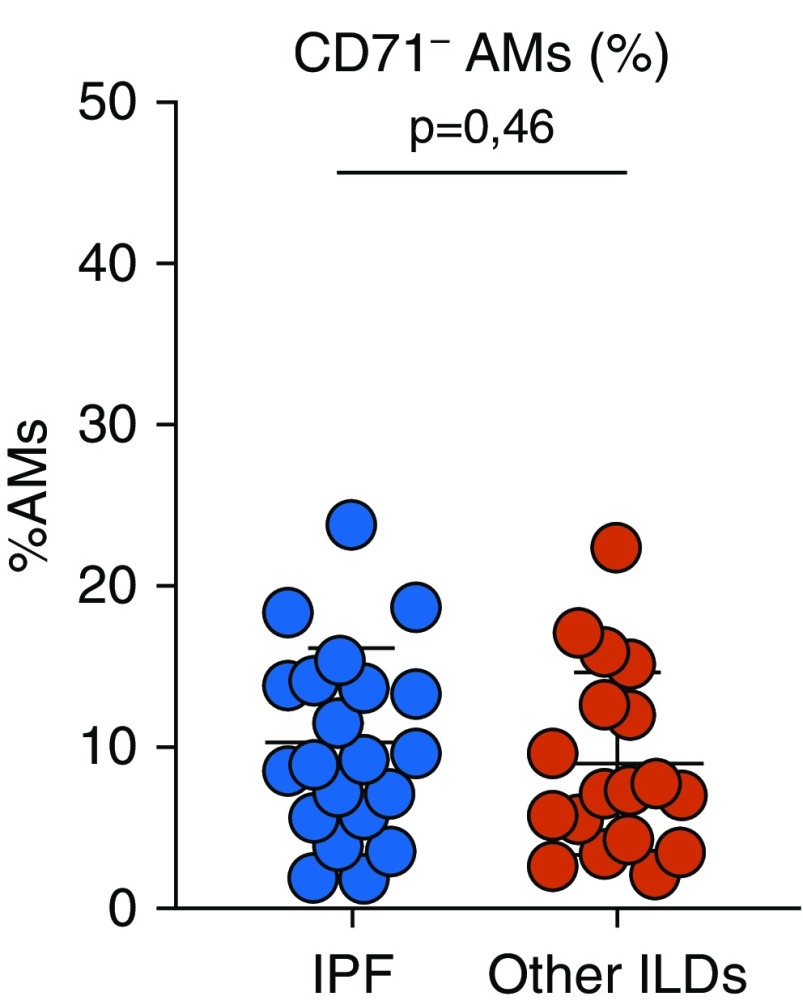

Applying the same gating strategy reported by Allden and coworkers to the above-mentioned flow-cytometry data, we were able to confirm the presence of two populations of AMs based on CD71 expression not only in patients with IPF but also in patients without IPF (Figure 1). In particular, the proportions of CD71− cells were similar between the two populations (10.90% ± 5.88% vs. 8.95% ± 5.75%; P = 0.46; Figure 2), although they appeared to be slightly lower than those reported by Allden and coworkers. Interestingly, among patients without IPF, the highest proportions of CD71− AMs were found in patients with a final diagnosis of Churg-Strauss syndrome and patients with stage II sarcoidosis.

Figure 1.

Gating strategy applied for flow-cytometry analysis and individuation of BAL CD71-expressing alveolar macrophages.

Figure 2.

Proportions of CD71− alveolar macrophages (AMs) in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and non-IPF BAL. ILD = interstitial lung disease.

As discussed by Allden and coworkers in their article, among other hypotheses, CD71− AMs could be an expression of a subpopulation of immature monocytes recruited into the alveolar space from the bloodstream during active inflammation/tissue injury, as was previously shown in a preclinical animal model of lung fibrosis (6). We believe that the lack of specificity about the presence of CD71− AMs in IPF that we show in this brief report supports the latter interpretation. Furthermore, the reported association between the proportion of CD71− cells and the clinical course of patients with IPF may reflect the ongoing fibrotic process that characterizes the rapidly progressive form of the disease and may also characterize other, non-IPF ILDs that in some cases display an accelerated pathological/clinical evolution. Although further studies on large populations of patients with ILD will be needed to confirm these preliminary observations, we believe that the study by Allden and coworkers is very promising and reinforces the role of BAL as a potential source of fundamental information in the field of translational medicine in respiratory diseases.

Footnotes

Supported by institutional funds from the University of Rome Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201906-1159LE on July 26, 2019

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Maher TM. Precision medicine in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. QJM. 2016;109:585–587. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcw117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allden SJ, Ogger PP, Ghai P, McErlean P, Hewitt R, Toshner R, et al. The transferrin receptor CD71 delineates functionally distinct airway macrophage subsets during idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:209–219. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201809-1775OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puxeddu E, Comandini A, Cavalli F, Pezzuto G, D’Ambrosio C, Senis L, et al. Iron laden macrophages in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: the telltale of occult alveolar hemorrhage? Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2014;28:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sangiuolo F, Puxeddu E, Pezzuto G, Cavalli F, Longo G, Comandini A, et al. HFE gene variants and iron-induced oxygen radical generation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:483–490. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00104814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee J, Arisi I, Puxeddu E, Mramba LK, Amicosante M, Swaisgood CM, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis express a complex pro-inflammatory, pro-repair, angiogenic activation pattern, likely associated with macrophage iron accumulation. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0194803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Misharin AV, Morales-Nebreda L, Reyfman PA, Cuda CM, Walter JM, McQuattie-Pimentel AC, et al. Monocyte-derived alveolar macrophages drive lung fibrosis and persist in the lung over the life span. J Exp Med. 2017;214:2387–2404. doi: 10.1084/jem.20162152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]