Abstract

Background:

Efficient and scalable models for HIV treatment are needed to maximize health outcomes with available resources. By adapting services to client needs, differentiated antiretroviral therapy (DART) has the potential to use resources more efficiently. We conducted a systematic review assessing the cost of DART in sub-Saharan Africa compared to the standard of care.

Methods:

We searched PubMed, Embase, Global Health, EconLit, and the grey literature for studies published between 2005 and 2019 that assessed the cost of DART. Models were classified as facility- vs community-based and individual vs group-based. We extracted the annual per-patient service delivery cost and incremental cost of DART compared to standard of care in 2018 USD.

Results:

We identified 12 articles that reported costs for 16 DART models in seven countries. The majority of models were facility-based (n=12) and located in Uganda (n=7). The annual cost per patient within DART models (excluding drugs) ranged from $27 to $889 (2018 USD). Of the 11 models reporting incremental costs, seven found DART to be cost saving. The median incremental savings per patient per year among cost-savings models was $67. Personnel was the most common driver of reduced costs, but savings were sometimes offset by higher overheads or utilization.

Conclusions:

DART models can save personnel costs by task shifting and reducing visit frequency. Additional economic evidence from community-based and group models is needed to better understand the scalability of DART. To decrease costs, programs will need to match DART models to client needs without incurring substantial overheads.

Keywords: Cost, Antiretroviral therapy, Differentiated care, Africa, HIV

INTRODUCTION:

In sub-Saharan Africa, over 25 million people are living with HIV of whom only 60% are on life-saving antiretroviral therapy (ART).1 Though additional scale-up of ART is needed, donor funding is expected to remain flat or decline.2 Thus, efficient and scalable models for ART delivery are needed to maximize health outcomes with available resources and reduce ongoing transmission. These strategies must increase access to high quality care and ensure long-term retention while addressing challenges such as healthcare worker shortages, clinic crowding, and other resource constraints.3

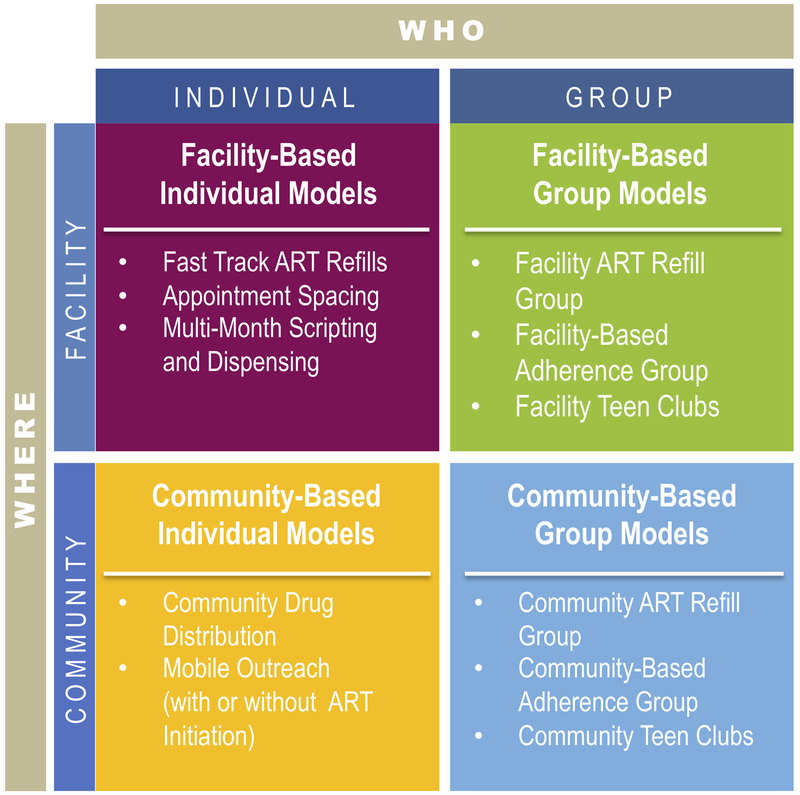

Differentiated service delivery (DSD) is “a client-centered approach that simplifies and adapts HIV services across the [HIV care] cascade, in ways that both serve the needs of [people living with HIV] better and reduce unnecessary burdens on the health system”.4 Differentiated ART (DART) models may alter the provider, intensity, location, or frequency of ART services for specific populations.5 Rather than a “one-size-fits-all” approach, DART models strive to allocate resources more effectively by tailoring delivery strategies to the needs of diverse groups of clients. DART models have been implemented across sub-Saharan Africa that differ from standard clinic-based care and are often targeted to stable patients (e.g., with undetectable viral loads) on ART.6,7 These approaches are classified into either group-based, in which the care of multiple clients is coordinated, or individual models.8 Models can be further classified into facility-based models that leverage existing infrastructure but tailor treatment services to different subgroups and community-based models that deliver ART closer to clients (Figure 1). Examples of DART models include multi-month prescribing, task shifting, community drug distribution points, and adherence clubs.

Figure 1:

Differentiated ART delivery framework (courtesy of ICAP at Columbia University48)

With an increasing number of models available, countries must assess factors such as client preference, quality of care, scalability, and efficiency to develop national strategies. Because DART models often require fewer professional staff and fewer, faster clinic visits, these models have the potential to be cost-saving compared to more intensive traditional models; however, it is unknown how often DART models actually decrease costs in practice. Cost is a key outcome in implementation science frameworks and directly affects intervention acceptability and adoption.9-11 In the context of limited funding for HIV programs,12 evidence on the cost of implementing differentiated models for ART delivery is necessary to inform policymakers deciding how to improve ART coverage while operating under constrained budgets. Our overall aim was to assess the cost of DART services compared to the standard of care. To address this aim, we conducted a systematic review to assess and summarize the available evidence for the cost of DART models in sub-Saharan Africa.

METHODS:

We conducted this review following the Cochrane Collaboration and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.13

Eligibility criteria

We considered articles with study data from 2005 or later describing the cost of differentiated ART models implemented in sub-Saharan Africa. Eligible DART models altered the service provider (e.g., task shifting), location of services (e.g., community-based ART delivery), or frequency of ARV (antiretroviral drug) refills (e.g., multi-month prescribing) compared to standard of care. We included studies that collected primary costing data; modeling studies without an empirical costing component were excluded. We restricted our review to articles reporting annual per-patient treatment costs and/or annual incremental per-patient treatment costs compared to standard of care. We extracted costs as implemented; modeled scenarios of staff substitution, price changes, or increased efficiency were excluded. We included costs from the provider perspective; therefore, our review does not include costs to the recipient of care. The review focuses on DART delivery models and does not include studies comparing laboratory monitoring procedures (e.g., CD4 vs. viral load testing) and client support.

Search strategy

We searched PubMed, Embase, Global Health Database, and EconLit for articles published between January 1, 2005 and May 23, 2019. We compiled keywords and MeSH terms related to antiretroviral therapy, service delivery models, cost, and sub-Saharan Africa. Full search terms for each database are provided in the Supplemental Digital Content (Tables S1-S4). We hand-searched the grey literature, including conference abstracts, reports from HIV funding agencies, non-governmental organizations, and program implementers, and HIV treatment consortia websites. We also cross-referenced citations in papers included in this analysis and consulted subject matter experts to identify additional references.

Data extraction and analysis

Three researchers (DAR, NL, NT) screened titles and abstracts identified in the search. Two researchers (DAR, NL) reviewed references identified for full-text screening. Discrepancies related to study inclusion were resolved through discussion with a third researcher (RVB).

Using a standardized form, we extracted key program features, including DART classification (facility- vs. community-based and individual- vs. group-based), country, year, client eligibility criteria, provider, ARV refill frequency, location of ART services, cost estimation method, nominal annual ARV drug costs per patient, and nominal fully-loaded annual treatment costs per patient. To compare costs, we first subtracted ARV drug costs from total ART costs due to sharp declines in drug prices over the review period (Supplemental Digital Content, Figure S1). We then inflated the remaining costs to 2018 US dollars (USD) using US gross domestic product (GDP) implicit price deflators.14 We also report incremental costs (when available) in 2018 USD by subtracting the annual treatment cost per patient per year (excluding drugs) under standard of care from that under DART. For studies describing multiple models, we reported results from each program separately.

RESULTS:

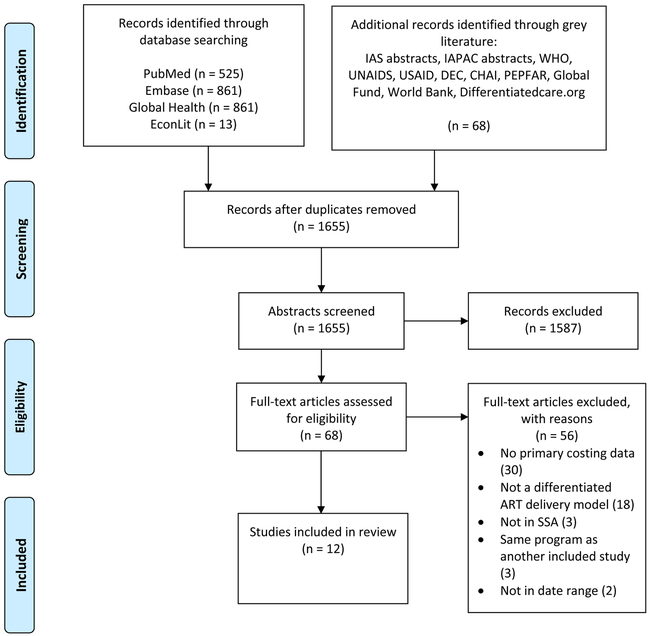

Our search identified 2,328 records, of which 673 were removed as duplicates (Figure 2). Of the 1,655 records remaining, we assessed 68 full-text articles for eligibility. Of these, we included 12 articles describing 16 DART models in the review (Table 1). Models were most commonly reported from Uganda (seven models) and South Africa (four models). Two studies (describing four models) included data from 2016 or later. Most studies estimated annual costs per patient by multiplying unit costs by the quantities of resources utilized over 12 months; in contrast, one study divided the total cost incurred in a calendar year by the total number of patients in care at mid-year.15 Among reported models, drug and non-drug costs reported for both DART models and comparator models declined over time in nominal and real USD, respectively (Figures S1-S3). The annual cost per patient within DART models (excluding drugs) ranged from $27 to $889 (2018 USD). Of the 11 models reporting incremental costs, seven found DART to be cost saving (Table 2, Figure S4). The median incremental savings per patient per year among cost-savings models was $67, whereas the median incremental cost per patient per year among DART models with higher costs compared to standard of care was $56 (2018 USD).

Figure 2:

PRISMA13 flow diagram for the selection of studies on the cost of differentiated ART delivery strategies in sub-Saharan Africa

Table 1: Service delivery models included in the systematic review.

ART = antiretroviral therapy; DART = differentiated ART delivery model

| Author (Pub Year) |

Model Description |

Country | Study Years |

DART eligibility criteria | Provider | Frequency | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FACILITY-BASED INDIVIDUAL | |||||||

| Babigumira (2011)16 | Task shifting | Uganda | 2005-2007 | Stable clients defined based on CD4, adherence, retention, disclosure to partner, and clinical status | Pharmacy nurse vs. doctor | Monthly | Regional HIV treatment center |

| Barton (2013)17 | Task shifting | South Africa | 2007-2010 | Cohort 1 = CD4 < 350, not on ART; cohort 2 = on ART ≥ six months |

Nurse vs. doctor | Monthly | Primary care clinics |

| Foster (2012)22 | Task shifting | South Africa | 2009-2010 | None given | Indirectly-supervised pharmacist assistant vs. nurse | Monthly for one year, then every two months | Primary care clinics |

| Jain (2015)18 | Task shifting | Uganda | 2011-2015 | Patients with CD4 ≥ 350 and asymptomatic clinical status | Nurse instead of doctor | Monthly for first two months, then every three months | Health center |

| Johns (2014)20 | Task shifting | Ethiopia | 2008-2009 | None given | Nurse or clinical officer vs. doctor for treating drug side effects and switching regimens | Not specified | Hospitals and health centers |

| Johns (2016)19 | Down-referral and task shifting | Nigeria | 2010-2012 | ART for at least one year | Nurse/pharmacist at spoke facility vs. doctor at hub facility | Not specified | Hospitals (hub) and health centers (spoke) |

| Long (2011)21 | Down-referral and task shifting | South Africa | 2008-2009 | Stable clients defined based on retention, clinical status, CD4 count, and viral load | Nurses instead of doctor | Every two months | Hospital or primary health clinic |

| Prust (2017)23 | Multi-month scripting | Malawi | 2016 | Stable clients defined based on age, retention, clinical status, adherence, and viral load | Consultation by nurse or clinician; dispensing by pharmacist | Every three months instead of monthly | Hospital, health center, or clinic |

| Prust (2017)23 | Fast-track refills | Malawi | 2016 | Stable clients defined based on age, retention, clinical status, adherence, and viral load | Consultation by a nurse or clinician; dispensing by health surveillance assistant | Every three months instead of monthly | Hospital, health center, or clinic |

| Shade (2017)24 | Multi-month scripting | Uganda, Kenya | 2015-2016 | All HIV-positive patients in study communities | Nurse-driven care with physician consultation if necessary | Every three months instead of monthly | Health facilities |

| Vu (2016)15 | Task shifting (Uganda Cares) | Uganda | 2012 | None given | Nurse-driven care with physician referral | Every 1-2 months | Health facilities |

| COMMUNITY-BASED INDIVIDUAL | |||||||

| Jaffar (2009)25 | Home-based delivery | Uganda | 2005-2009 | None given | Community health workers supported by counsellors and medical officers | Monthly | Home |

| Vu (2016)15 | Community distribution points (TASO) | Uganda | 2012 | Stable clients | Nurses and expert clients with supervision by doctors | Every 2-3 months | Community locations |

| Vu (2016)15 | Community-based delivery (Kitovu Mobile) | Uganda | 2012 | None given | Expert clients with supervision by doctors | Every 1-2 months | Community locations |

| FACILITY-BASED GROUP | |||||||

| Bango (2016)30 | Adherence clubs | South Africa | 2007-2011 | Stable clients defined based on retention, CD4 count, viral load, and clinical status | Groups of 25-30 patients receive symptom screening, education, and medication refills from lay counsellor. Annual clinical check-ups done by nurse. | Every two months instead of monthly | Clinic |

| COMMUNITY-BASED GROUP | |||||||

| Prust (2017)23 | Community ART groups | Malawi | 2016 | Stable clients defined based on age, retention, CD4 count, viral load, and clinical status | Peer-led groups manage drug distribution and peer discussion. Nurse/clinician provides facility consultation for visiting member | One group member visits each month; each individual attends ~ every six months | Community locations and health facility |

Table 2: Economic results from included studies.

Costs are reported from the provider’s perspective. USD = United States Dollar; ARV = antiretroviral drug; ART = antiretroviral therapy; DART = differentiated ART delivery model; ISPA = indirectly-supervised pharmacist assistant. *Negative values indicate DART model costs less than comparator. Positive values indicate DART model costs more than comparator.

| Author (Pub Year) |

Model Description |

Country | USD Year | Annual DART cost per patient (Nominal USD) |

Annual DART cost per patient, excluding ARVs (2018 USD) |

Annual incremental cost per patient (DART - Comparator) (2018 USD)* |

Drivers of incremental cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FACILITY-BASED INDIVIDUAL | |||||||

| Babigumira (2011)16 | Task shifting | Uganda | 2009 | $496 | $294 | −$132 | Personnel |

| Barton (2013)17 | Task shifting | South Africa | 2009 | $400 (Cohort 1); $481 (Cohort 2) | $326 (Cohort 1); $233 (Cohort 2) | $101 (Cohort 1); $69 (Cohort 2) | Personnel, visit length and frequency, start up, supervision |

| Foster (2012)22 | Task shifting | South Africa | 2010 | NA | ISPA: $71 Nurse-driven: $114 | ISPA vs. pharmacist: $12 Nurse-driven vs. pharmacist: $56 | Number of visits, personnel |

| Jain (2015)18 | Task shifting | Uganda | 2012 | $987 (baseline), $628 (steady state) | $889 (baseline), $494 (steady state) | NA | Personnel, lab testing |

| Johns (2014)20 | Task shifting | Ethiopia | 2011 | $216 | $106 | $8 | Reduced personnel costs offset by higher costs for training, supervision, and drugs |

| Johns (2016)19 | Down-referral and task shifting | Nigeria | 2011 | $265 (Site 1); $324 (Site 2) | $165 (Site 1), $247 (Site 2) | $62 (Site 1), -$166 (Site 2) | Personnel |

| Long (2011)21 | Down-referral and task shifting | South Africa | 2009 | $486 | $260 | −$91 | Personnel, lab tests, fixed costs |

| Prust (2017)23 | Multi-month scripting | Malawi | 2016 | $121 | $28 | −$15 | Personnel |

| Prust (2017)23 | Fast-track refills | Malawi | 2016 | $121 | $27 | −$15 | Personnel |

| Shade (2017)24 | Multi-month scripting | Uganda, Kenya | 2016 | $270 (Uganda), $309 (Kenya) | $166 (Uganda); $178 (Kenya) | NA | NA |

| Vu (2016)15 | Task shifting (Uganda Cares) | Uganda | 2009 | $257 | $76 | NA | NA |

| COMMUNITY-BASED INDIVIDUAL | |||||||

| Jaffar (2009)25 | Home-based delivery | Uganda | 2008 | $793 | $438 | −$51 | Personnel |

| Vu (2016)15 | Community distribution points (TASO) | Uganda | 2012 | $322 | $201 | NA | NA |

| Vu (2016)15 | Community-based delivery (Kitovu Mobile) | Uganda | 2012 | $404 | $258 | NA | NA |

| FACILITY-BASED GROUP | |||||||

| Bango (2016)30 | Adherence clubs | South Africa | 2011 | $300 | $178 | −$83 | Personnel |

| COMMUNITY-BASED GROUP | |||||||

| Prust (2017)23 | Community ART groups | Malawi | 2016 | $122 | $29 | −$14 | Personnel |

Facility-based individual models

Eleven of the 16 models identified in the review are classified as facility-based individual models (Table 1). Eight analyses examined task-shifting. Six of these compared task shifting from doctors to either nurses, pharmacists, or both.16-21 In two of these studies, nurse-led care occurred after referral to a lower-tier health facility.19,21 A study from South Africa by Foster et al. involved task shifting from pharmacists to either nurses or indirectly-supervised pharmacist assistants and another model from Malawi (Prust et al.) described dispensing by health surveillance assistants instead of a nurse or pharmacy staff.22,23 Three models increased the drug prescribing interval from one to three months.23,24 Of these, one program in Malawi (Prust et al.) additionally enabled stable clients to alternate clinical consultations with refill-only visits (fast-tracked refills).23 Six models explicitly included only stable clients (though definitions varied)16-19,21,23, one model analyzed costs for both stable clients as well as clients initiating ART17, and the rest did not specify client eligibility criteria.15,18,22,24

The annual per-patient HIV treatment costs reported by included studies are shown in Table 2. In an analysis from Malawi of multi-month prescribing and fast-track refills (Prust et al.), the cost per patient (excluding drugs) in 2018 USD was estimated to be $28 and $27, respectively.23 In contrast, a 2012 study in Uganda of a nurse-driven streamlined ART delivery found costs (excluding drugs) of $889 (as observed, which included low volumes during study initiation) and $494 (at steady state, once full enrollment had been achieved) per patient per year.18 This study had high salaries due to the employment of research staff in the provision of care; modeled scenarios involving government personnel and increased efficiency projected costs as low as $236 (2018 USD, excluding ARVs) and $143 (without viral load testing).18

Eight studies of facility-based individual models reported incremental costs with respect to standard of care. Of these, four models reported reduced costs in the DART model due to lower personnel costs, which were achieved through task shifting to a lower cadre in two models16,21, reducing visit frequency in one model (Prust et al.,23 multi-month prescribing), and both in one model (Prust et al., 23 fast-track refills). The incremental savings ranged from $15 to $132 per patient per year (2018 USD).16,23 All of the models reporting incremental savings were evaluated among stable clients. Babigumira et al. found that a pharmacy-based refill program implemented in Uganda could save $132 per patient per year (2018 USD) by task shifting from doctors to pharmacy staff.16 An analysis by Long et al. in South Africa found that stable patients who were down-referred from doctor-led care at central hospitals to nurses at primary health centers incurred lower personnel, lab testing, and non-ARV drug costs.21 The authors attributed increased drug and lab test costs to doctors’ power to prescribe beyond what is mandated by guidelines. In comparison, three studies reported higher costs in the task shifted model, with incremental costs ranging from $8 to $101 per patient per year (2018 USD).17,20,22 In two of these, additional start-up and supervision costs offset the lower per-visit personnel costs in the task shifted model.17,20 In a randomized trial of nurse-led vs. doctor-led care in South Africa (Barton et al.), nurse-led care resulted in more frequent and longer clinical visits.17 Among clients with CD4 ≤ 350 who had not yet initiated ART, nurse-led care also resulted in more doctor visits, which the authors hypothesized reflected closer adherence to physician referral procedures. Combined with set-up and implementation costs incurred in the nurse-led model, nurse-led care resulted in higher costs per-patient for both new clients (Cohort 1, $101 per patient per year) and existing clients (Cohort 2, $69 per patient per year). A study by Foster et al. also reported increased visit frequency in the task shifted DART model, such that despite a lower cost per visit using either indirectly-supervised pharmacist assistants or nurses compared to pharmacists, the overall cost per year was higher.22 The authors predicted that annual costs in the task-shifted models, which were implemented in newer facilities, would decrease over time as the proportion of stable patients (who have longer refill intervals) increased. An analysis from Nigeria (Johns et al.) compared nurse-led care at primary health centers to doctor-led care hospitals and found mixed results, with one state (Cross Rivers) having increased costs ($66 higher per patient per year in the decentralized model) and the other (Kaduna) having lower costs ($166 lower per patient per year in the decentralized model).19 The hospital in Cross Rivers had relatively low salaries and involved counsellors in treatment, reducing the personnel cost savings that could be achieved through decentralization. Furthermore, the hospital operated at high volumes, so scale economies may explain the lower per-patient costs as compared to the primary health center. In contrast, labor costs per visit in the hospital in Kaduna were over five times higher than those in the hospital in Cross Rivers. As a result, task shifting to nurses in the decentralized facility in Kaduna resulted in substantial savings despite increased visit frequency.

Community-based individual models

Two studies described three community-based individual models, all in Uganda.15,25 In a randomized trial from 2005-2009, participants in the home-based arm initiated ART at a clinic and then received monthly refills and symptom screening at home, returning to the clinic every six months for a clinical consultation with a medical officer.25 In an economic evaluation conducted concurrently with the trial, the annual cost per patient enrolled in home-based care was estimated to be $51 (2018 USD) lower than under facility-based care. While transportation, overheads (costs not directly attributable to a patient’s medical care), and capital costs were higher in the home-based arm, these were offset by lower personnel costs using lay health workers for refills rather than nurses and clinical officers at the health facility.

Another study in Uganda described two community-based models of ART delivery that both used a combination of nurses and expert clients for service delivery.15 One program implemented by The AIDS Support Organization (TASO, a Ugandan non-governmental organization) used community-based drug distribution points (CDDPs) for ARV refills. The CDDPs were supported by central clinics and allowed nurses and expert clients to dispense drugs to stable patients. In a more decentralized model implemented by Kitovu Mobile, mobile units of expert clients provided drug refills and adherence counseling at 111 non-facility-based community locations in 10 districts in southwestern Uganda. This model incurred a higher annual per-patient cost ($258 in 2018 USD, excluding drugs) than the CDDP model ($201), which the authors attributed to increased refill location flexibility and higher numbers of visits per patient per year in the mobile unit model compared to CDDPs. The analysis did not cost facility-based care but noted that both models had comparable costs to facility-based estimates from other studies.26-29

Group models

Two articles analyzed group-based models. A study by Bango et al. of a Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) program in South Africa described facility-based adherence clubs that included groups of 25-30 stable clients managed by a lay counsellor.30 Groups met at the health facility and received symptom screening and fast-tracked ART refills every two months as well as an annual clinical consultation with a nurse. Compared to standard facility-based care, the annual per patient cost in the adherence club was $83 lower (2018 USD) due to lower personnel unit costs and fewer annual visits. In Malawi, Prust et al. described a community ART group (CAG) model for stable clients in which one client visits the health facility each month to receive a clinical consultation and to pick up ART refills for the entire group.23 Refills are distributed to the rest of the group in a community setting with peer-led discussion. By rotating who picks up the medication, each client travels to the facility about once every six months. The analysis found that the CAG model saved $14 per client (2018 USD) per year by reducing the number of encounters with facility personnel.

DISCUSSION:

In this systematic review, we found that DART models often but not always reduced costs relative to standard of care. Personnel costs were the most common driver of cost savings due to task shifting client encounters to lower cadres or, for multi-month prescribing or community ART groups, reducing clinic visit frequency. However, several studies reported that task shifted and decentralized models incurred higher costs due to increased numbers of visits or significant start-up and supervision costs. While the importance of start-up and supervision costs may be diminish over time since implementation, these results highlight the importance of conducting empirical costing studies to both measure resource utilization and capture costs above service delivery incurred in DART programs.

Differences in the reported annual per-patient treatment cost between studies may be attributed to several factors, which restricts the generalizability of the findings. The studies included in this review took place across a range of years and countries, limiting comparability and the utility of a summary measure of the incremental cost of differentiated care. For example, the lowest cost was reported from a study in Malawi, which has lower personnel costs compared to other sub-Saharan African countries.31 In addition, as HIV care has become increasingly decentralized and task shifted over time,32,33 lower costs (after excluding ARV drug costs) reported in more recent studies of DART models (Figure S2) may reflect decreases in the cost of standard of care (Figure S3). If standard of care per-patient costs are declining over time, then the potential savings per-patient under DART may diminish. Nevertheless, DART implementation could still translate to substantial reductions in overall spending if models can be successfully scaled to a large number of patients, or if improved retention and adherence can impact ongoing transmission and prevent new HIV cases. A modeling study estimated that widespread implementation of DART models based on age and clinical stability could save nearly 18% of costs over a five-year period.34 Furthermore, DART models may address other health system constraints that are not necessarily reflected in unit costs, such as human resource shortages and clinic crowding.35

This review also identified several evidence gaps. The majority of studies reported care models for stable clients, but DART models are also needed for unstable patients who could benefit from more intensive care as well as for key populations who might benefit from alternative service delivery strategies.36 Several models did not report client eligibility criteria or client characteristics, which limits our understanding of the potential generalizability and scalability of the model. The two studies that evaluated multi-month prescribing only considered intervals of up to three months, while WHO guidelines recommend intervals of up to six months for stable clients.37 Economic evaluations from ongoing studies of six month dispensing intervals will help fill this gap.38,39 We identified relatively few community-based individual models that spanned a spectrum of decentralization of ART delivery, from home to CDDPs. Health systems considering community-based ART delivery will need to optimize the tradeoff between accessibility and cost of implementation, which will vary by context and deserves evaluation. In addition, we found only two group-based models that reported costs, indicating that additional economic evidence is needed to inform scale-up of such models. The per-patient cost of CAGs in Malawi was similar to fast-tracked refills and multi-month prescribing, but only six percent of eligible patients were enrolled in CAGs compared to over 70% in the other two models.23 While several studies have demonstrated high retention in pilot studies of group-based models,40,41 a recent randomized trial reported high dropout from club-based care within two years of enrollment.42 Assessing the cost-effectiveness of group-based models will require further research into scalability and long-term sustainability.

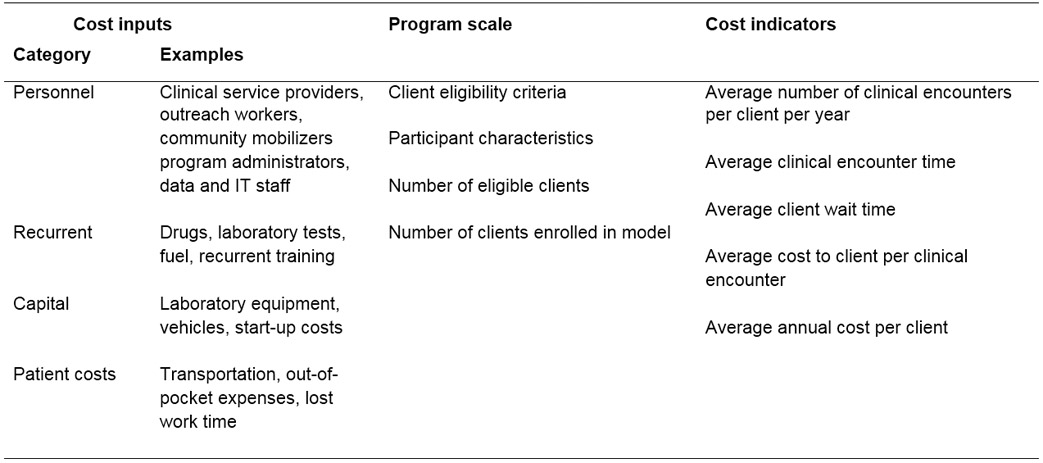

This review has several limitations. While most studies of the incremental cost of DART models in this review found lower costs under DART implementation, it is possible that findings of higher costs of DART models are less likely to be published. Our review focused only on provider-level costs, but DART models also can impact client costs and outcomes. A previous review found that all identified studies reported decreased client costs in DART models compared to standard of care.7 Decisions about DART implementation must consider client benefits in addition to provider costs. Cost-effectiveness analyses should consider how the benefits of DART are distributed across the population in order to ensure equity in access to high-quality HIV care.43 Last, differences in costs across included studies could reflect variation in methodology and reporting practices. Standardized methods for estimating and reporting the cost of HIV programs are needed to improve the comparability and utility of cost data.44 Using these data, facilities and programs can tailor DART models for their patient population and context. In addition to routine monitoring of program outcomes indicators,45,46 we recommend programs collect a minimum economic data set, including above service-delivery costs such as supervision, administration, and training, and report key indicators of cost and efficiency (Table 3). These data also have the potential to inform budget impact analyses.47

Table 3:

Minimum economic dataset for differentiated ART delivery programs

|

The results from this review have implications for future implementation science studies. Researchers and program implementers designing DART models should consider factors such as personnel cadre and refill interval to maximize ART service efficiency. The dearth of economic evidence from community- and group-based models hinders comparisons to facility-based individual approaches. When feasible, head-to-head comparisons of DART models can help decision makers select efficient strategies for local contexts. Last, resource utilization should be compared with health outcomes in economic evaluations to identify cost-effective service delivery strategies.

In conclusion, the majority of economic evidence for DART models comes from facility-based individual models. DART models can save personnel costs by task shifting and reducing visit frequency, but these savings may be offset by increased start-up and supervision costs. Additional economic evidence from community-based and group models is needed to better understand the scalability and sustainability of differentiated ART delivery.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

We would like to thank Dr. Miriam Rabkin and Dr. Wafaa El-Sadr for scientific input and guidance, Diana Louden for assistance in designing the search strategy, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation for support.

Sources of support: This work was funded by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1152764). DAR is supported by National Institutes of Health/Health and Human Services T32 GM007266/GM/NIGMS.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data from this manuscript were presented at the 22nd International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2018, Amsterdam, July 23-27, 2018)

REFERENCES:

- 1.UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS Statistics: 2018 Fact Sheet. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet. Published 2018. Accessed April 11, 2019.

- 2.Kaiser Henry J Family Foundation and UNAIDS. Donor Government Funding for HIV in Low- and Middle-Income Countries in 2018.; 2019.

- 3.Boyd MA, Cooper DA. Optimisation of HIV care and service delivery: doing more with less. Lancet. 2012;380(9856):1860–1866. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61154-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grimsrud A, Bygrave H, Doherty M, et al. Reimagining HIV service delivery: the role of differentiated care from prevention to suppression. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):21484. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.1.21484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duncombe C, Rosenblum S, Hellmann N, et al. Reframing HIV care: putting people at the centre of antiretroviral delivery. Trop Med Int Heal. 2015;20(4):430–447. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis N, Kanagat N, Sharer M, Eagan S, Pearson J, Amanyeiwe U “Ugo.” Review of differentiated approaches to antiretroviral therapy distribution. AIDS Care. 2018;30(8):1010–1016. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1441970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagey JM, Li X, Barr-Walker J, et al. Differentiated HIV care in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review to inform antiretroviral therapy provision for stable HIV-infected individuals in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2018;30(12):1477–1487. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1500995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grimsrud A, Barnabas R V, Ehrenkranz P, Ford N. Evidence for scale up: the differentiated care research agenda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(Suppl 4):22024. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.5.22024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for Implementation Research: Conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda. Adm Policy Ment Heal Ment Heal Serv Res. 2011;38(2):65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Padian NS, Holmes CB, McCoy SI, Lyerla R, Bouey PD, Goosby EP. Implementation Science for the US Presidentʼs Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(3):199–203. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820bb448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Global Burden of Disease Health Financing Collaborator Network JL, Haakenstad A, Micah A, et al. Spending on health and HIV/AIDS: domestic health spending and development assistance in 188 countries, 1995-2015. Lancet (London, England). 2018;391(10132):1799–1829. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30698-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Energy Information Administration. GDP Implicit Price Deflator. https://www.eia.gov/opendata/qb.php?category=1039997&sdid=STEO.GDPDIUS.A. Published 2019. Accessed June 7, 2019.

- 15.Vu L, Waliggo S, Zieman B, et al. Annual cost of antiretroviral therapy among three service delivery models in Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(5 Suppl 4):20840. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.5.20840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Babigumira JB, Castelnuovo B, Stergachis A, et al. Cost Effectiveness of a Pharmacy-Only Refill Program in a Large Urban HIV/AIDS Clinic in Uganda van Baal P, ed. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e18193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barton GR, Fairall L, Bachmann MO, et al. Cost-effectiveness of nurse-led versus doctor-led antiretroviral treatment in South Africa: pragmatic cluster randomised trial. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18(6):769–777. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jain V, Chang W, Byonanebye DM, et al. Estimated Costs for Delivery of HIV Antiretroviral Therapy to Individuals with CD4+ T-Cell Counts >350 cells/uL in Rural Uganda. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0143433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johns B, Baruwa E. The effects of decentralizing anti-retroviral services in Nigeria on costs and service utilization: two case studies. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(2):182–191. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czv040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johns B, Asfaw E, Wong W, et al. Assessing the Costs and Effects of Antiretroviral Therapy Task Shifting From Physicians to Other Health Professionals in Ethiopia. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(4):e140–e147. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Long L, Brennan A, Fox MP, et al. Treatment outcomes and cost-effectiveness of shifting management of stable ART patients to nurses in South Africa: an observational cohort Ford N, ed. PLoS Med. 2011;8(7):e1001055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster N, McIntyre D. Economic evaluation of task-shifting approaches to the dispensing of anti-retroviral therapy. Hum Resour Health. 2012;10(1):32. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-10-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prust ML, Banda CK, Nyirenda R, et al. Multi-month prescriptions, fast-track refills, and community ART groups: results from a process evaluation in Malawi on using differentiated models of care to achieve national HIV treatment goals. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(Suppl 4):21650. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.5.21650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shade SB, Osmand T, Luo A, et al. Costs of streamlined HIV care delivery in rural Ugandan and Kenyan clinics in the SEARCH Studys. AIDS. 2018;32(15):2179–2188. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaffar S, Amuron B, Foster S, et al. Rates of virological failure in patients treated in a home-based versus a facility-based HIV-care model in Jinja, southeast Uganda: a cluster-randomised equivalence trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9707):2080–2089. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61674-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menzies NA, Berruti AA, Berzon R, et al. The cost of providing comprehensive HIV treatment in PEPFAR-supported programs. AIDS. 2011;25(14):1753–1760. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283463eec [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tagar E, Sundaram M, Condliffe K, et al. Multi-country analysis of treatment costs for HIV/AIDS (MATCH): facility-level ART unit cost analysis in Ethiopia, Malawi, Rwanda, South Africa and Zambia. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e108304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galárraga O, Wirtz VJ, Figueroa-Lara A, et al. Unit Costs for Delivery of Antiretroviral Treatment and Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29(7):579–599. doi: 10.2165/11586120-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larson BA, Bii M, Henly-Thomas S, et al. ART treatment costs and retention in care in Kenya: a cohort study in three rural outpatient clinics. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bango F, Ashmore J, Wilkinson L, van Cutsem G, Cleary S. Adherence clubs for long-term provision of antiretroviral therapy: cost-effectiveness and access analysis from Khayelitsha, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2016;21(9):1115–1123. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tagar E, Sundaram M, Condliffe K, et al. Multi-country analysis of treatment costs for HIV/AIDS (MATCH): facility-level ART unit cost analysis in Ethiopia, Malawi, Rwanda, South Africa and Zambia. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e108304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zachariah R, Ford N, Philips M, et al. Task shifting in HIV/AIDS: opportunities, challenges and proposed actions for sub-Saharan Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103(6):549–558. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Callaghan M, Ford N, Schneider H. A systematic review of task- shifting for HIV treatment and care in Africa. Hum Resour Health. 2010;8(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-8-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barker C, Dutta A, Klein K. Can differentiated care models solve the crisis in HIV treatment financing? Analysis of prospects for 38 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(Suppl 4):21648. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.5.21648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mikkelsen E, Hontelez JAC, Jansen MPM, et al. Evidence for scaling up HIV treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: A call for incorporating health system constraints. PLOS Med. 2017;14(2):e1002240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. Key Considerations for Differentiated Antiretroviral Therapy Delivery for Specific Populations: Children, Adolescents, Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women and Key Populations.; 2017.

- 37.World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection.; 2016. [PubMed]

- 38.Fatti G, Ngorima-Mabhena N, Chirowa F, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of 3- vs. 6-monthly dispensing of antiretroviral treatment (ART) for stable HIV patients in community ART-refill groups in Zimbabwe: study protocol for a pragmatic, cluster-randomized trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):79. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-2469-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoffman R, Bardon A, Rosen S, et al. Varying intervals of antiretroviral medication dispensing to improve outcomes for HIV patients (The INTERVAL Study): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18(1):476. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2177-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Decroo T, Koole O, Remartinez D, et al. Four-year retention and risk factors for attrition among members of community ART groups in Tete, Mozambique. Trop Med Int Heal. 2014;19(5):514–521. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vandendyck M, Motsamai M, Mubanga M, et al. Community-Based ART Resulted in Excellent Retention and Can Leverage Community Empowerment in Rural Lesotho, A Mixed Method Study. HIV/AIDS Res Treat - Open J. 2015;2(2):44–50. doi: 10.17140/HARTOJ-2-107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanrahan CF, Schwartz SR, Mudavanhu M, et al. The impact of community- versus clinic-based adherence clubs on loss from care and viral suppression for antiretroviral therapy patients: Findings from a pragmatic randomized controlled trial in South Africa Newell M-L, ed. PLOS Med. 2019;16(5):e1002808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Verguet S, Kim JJ, Jamison DT. Extended Cost-Effectiveness Analysis for Health Policy Assessment: A Tutorial. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(9):913–923. doi: 10.1007/s40273-016-0414-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vassall A, Sweeney S, Kahn J, et al. Reference Case for Estimating the Costs of Global Health Services and Interventions.; 2017.

- 45.Ehrenkranz PD, Calleja JM, El-Sadr W, et al. A pragmatic approach to monitor and evaluate implementation and impact of differentiated ART delivery for global and national stakeholders. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(3):e25080. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reidy WJ, Rabkin M, Syowai M, Schaaf A, El-Sadr WM. Patient- and program-level monitoring of differentiated service delivery for HIV. AIDS. 2017;32(3):1. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bilinski A, Neumann P, Cohen J, Thorat T, McDaniel K, Salomon JA. When cost-effective interventions are unaffordable: Integrating cost-effectiveness and budget impact in priority setting for global health programs. PLOS Med. 2017;14(10):e1002397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. ICAP. https://icap.columbia.edu/. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.