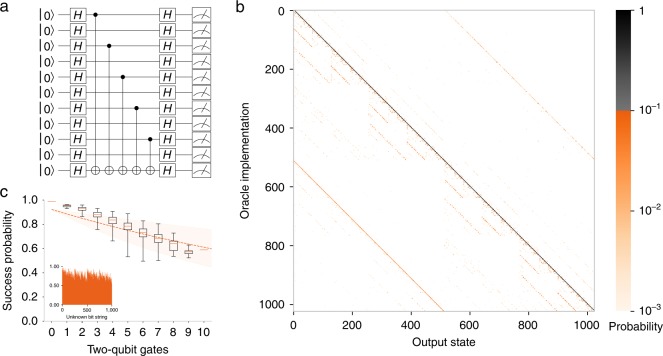

Fig. 3.

Bernstein–Vazirani (BV) algorithm. a Shows a textbook implementation of the BV algorithm with hidden bit string 1010101010. b Shows the full output distribution for all 1024 oracle implementations calculated from 500 iterations of each oracle after conditioning on the ancilla. c Shows the probability (inset plot) of detecting the encoded hidden bit string for all 1024 oracle implementations, as a function of the number of ones in the binary representation of the unknown bit string, which is equivalent to the number of two-qubit gates (n), which is maximally 10 in the case of this algorithm. The boxplots highlight the minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum of the data. Note that there is only one oracle implementation for n = 0, 10, which explains the lower observed variances for these points. In contrast, there are many more oracles that consist of five two-qubit gates, where each included gate has slightly different fidelity. This leads to increased variance across the full set of five two-qubit gate oracle implementations. The shaded area spans the expected fidelity (excluding crosstalk errors) (where is the fidelity of two-qubit gates, is the fidelity of single-qubit gates, and is the average SPAM fidelity) if all of our gates share the best measured fidelity or, alternatively, all share the worst fidelity. The result of a shared average fidelity is plotted as a dashed line. The average probability of success is 78 with 899 out of the 1024 oracle implementations exceeding the BQP single-shot success threshold.