Figure 3.

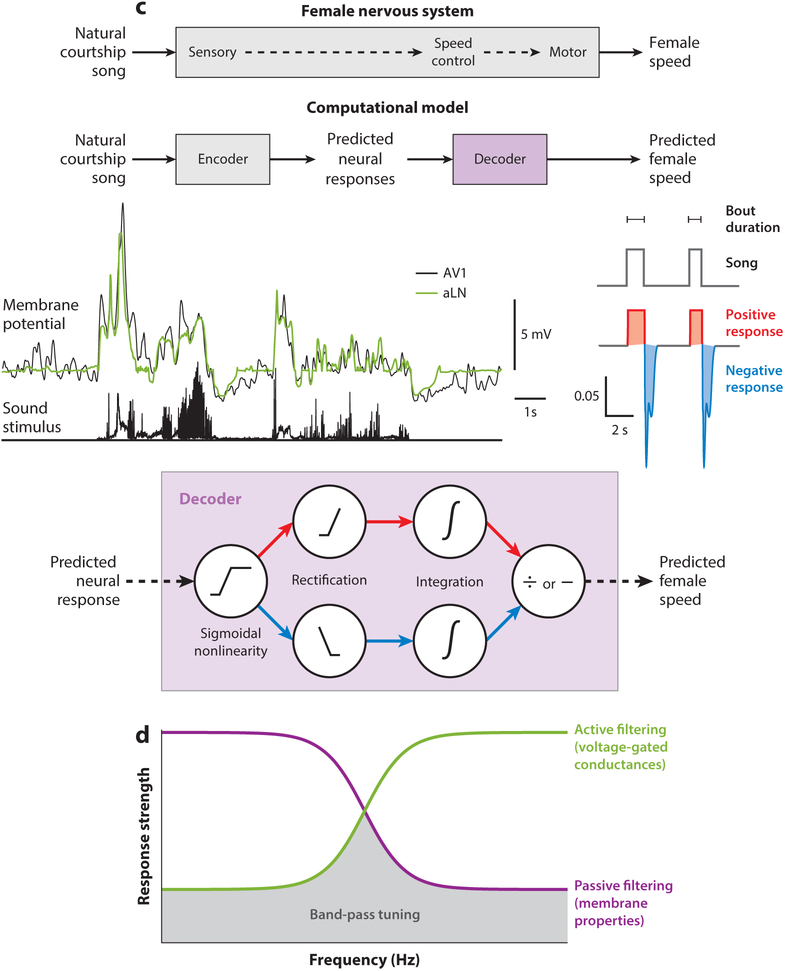

Mechanisms for temporal pattern recognition in insects. (a) Cricket phonotaxis behavior is tuned to species-specific pulse periods, or the time intervals between successive pulses (left) (Schöneich et al. 2015). The responses of the neuron LN4 match behavioral tuning. LN4 achieves its interval tuning through a delay line and coincidence detection mechanism (right). AN1 provides sound-evoked excitation to LN2 and LN3. LN2 in turn inhibits LN5, which produces a postinhibitory rebound at the end of each song pulse. LN3 acts as a coincidence detector by combining postinhibitory rebound from LN5 with excitation from AN1. LN3 responds when the rebound co-occurs with AN1 excitation, which happens only for conspecific intervals. Finally, interval selectivity is enhanced by LN4, which spikes only when input from LN3 is maximal. Panel a adapted from (left) Schöneich et al. (2015) and (right) Hedwig (2016). (b) Grasshopper behavioral responses are selective for a narrow range of syllable and pause durations (top left) (Creutzig et al. 2010). An increase in temperature causes shorter syllables and pauses but leaves the syllable:pause ratio constant. The AN12 neuron in the metathoracic ganglion exhibits temperature-independent selectivity for conspecific syllable:pause ratios (top right) (Creutzig et al. 2009). AN12 generates bursts at the onset of each syllable, with the number of spikes per burst depending on the duration of the preceding pause but not syllable. Higher temperatures cause shorter pauses, evoking fewer spikes per burst, but more syllables per second, evoking more bursts (bottom). The overall result is the same total number of spikes per second. AN12’s responses are hypothesized to result from interactions between excitation and inhibition. AN12 could receive an excitatory copy of the adapted responses of auditory receptors and a delayed, inhibitory, low-pass version of the adapted responses. The upper subpanels of panel b are adapted with permission from Creutzig et al. (2009). (c) In flies, female locomotor speed is sensitive to song bout duration on timescales up to 1 s (Clemens et al. 2015). This bout duration sensitivity could arise from the integration of positive bout duration–dependent voltage changes during song and negative bout duration–independent voltage changes at song offset in early auditory neurons (middle). Summing the positive responses over a defined window provides a measure of the total amount of song, and counting the number of negative responses provides a measure of the total number of bouts. Dividing total song amount by total number of bouts provides an estimate of bout duration. Panel c adapted with permission from Clemens et al. (2015). (d) Band-pass frequency tuning (gray shading) in Drosophila B1 neurons results from a combination of passive and active filtering mechanisms (Azevedo & Wilson 2017). Active processes, such as voltage-gated conductances, suppress responses at low frequencies, and passive membrane properties, such as capacitive and leak currents, suppress responses at high frequencies. Variation in the relative strengths of passive and active filtering properties within B1 neurons gives rise to variation in frequency selectivity across the population. Abbreviations: AN, ascending neuron; LN, local neuron.