Abstract

The aim of the current study was to assess reliability of the Functional Threshold Power test (FTP) and the corresponding intensity sustainable for 1-hour in a “quasi-steady state”. Highly-trained athletes (n = 19) completed four non-randomized tests over successive weeks on a Wattbike; a 3-min incremental test (GxT) to exhaustion, two 20-min FTP tests and a 60-min test at computed FTP (cFTP). Power at cFTP was calculated by reducing 20-min FTP data by 5% and was compared with power at Dmax and lactate threshold (TLac). Ventilatory and blood lactate (BLa) responses to cFTP were measured to determine whether cFTP was quasi-steady state. Agreement between consecutive FTP tests was quantified using a Bland-Altman plot with 95% limits of agreement (95% LoA) set at ± 20 W. Satisfactory agreement between FTP tests was detected (95% LoA = +13 and −17 W, bias +2 W). The 60-min effort at cFTP was successfully completed by 17 participants, and BLa and ventilatory data at cFTP were classified as quasi-steady state. A 5% increase in power above cFTP destabilized BLa data (p < 0.05) and prompted VO2 to increase to peak GxT rates. The FTP test is therefore deemed representative of the uppermost power a highly-trained athlete can maintain in a quasi-steady state for 60-min. Agreement between repeated 20-min FTP tests was judged acceptable.

Keywords: Functional threshold power, incremental exercise test, critical power, maximum lactate steady state

INTRODUCTION

Functional threshold power (cFTP) is defined as the uppermost power sustainable for 60-min in a quasi-steady state (1). Data for cFTP is calculated as 95% of the mean power output during a maximal 20-min effort, the sole outcome measure assessed is power, see Table 1. This 20-min maximum effort does not reflect a specific energy system, rather a performance, derived from all available energetics. Dissimilarly, exercise physiologists commonly break-down the elements of whole-body energetics to enhance our understanding of how a competitive performance is derived, such as blood lactate (BLa) and ventilation to determine physiological thresholds; namely, load at lactate threshold (TLac), load at ventilatory threshold (Tvent) and load at Dmax (4). Ordinarily these results are used to appraise the effectiveness of the preceding training and to direct future preparation. However, BLa and ventilation measures are impacted upon by test format; namely, increment duration and magnitude (4, 24). A new power-based test may add insight into these already established physiological test indices.

Table 1.

Test protocol for assessing FTP(1)

| Duration | Description | % FTP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warm-up | 20-min | Endurance pace | 65 |

| 3 by 1-min with 1-min recoveries | Fast pedaling, 100 rev·min−1 | Not applicable | |

| 5-min | Easy riding | 65 | |

| 5-min | Time-trial | Maximum effort | |

| 10-min | Easy riding | 65 | |

| FTP test | 20-min | Time-trial | Maximum effort |

| Cool down | 10 to 15-min. | Easy riding | 65 |

(FTP) – Functional threshold power, (min) – minute, (rev·min−1) – revolutions per minute

The authors of the FTP test (1) state that the test can be trialed satisfactorily in the field. Irrespective, we felt it prudent, at this juncture, to appraise the FTP test in a controlled laboratory setting. The complexities of controlling the multitude of variables required for ecological validation were beyond the scope of the current investigation.

The first hypothesis of the current study was that, in a highly-trained athletic cohort, repeated 20-min FTP tests would be reliable and reproducible. The second hypothesis was that the FTP test was sustainable for 60-min. The prefatory description “quasi-steady state” BLa and VO2 was assessed using already established definitions of steady state BLa (20) and VO2 (26). The interchangeability of cFTP with the following mathematical calculations of a threshold intensity; Tvent, TLac and Dmax were examined. The aim was to find a comparable intensity to cFTP. The variation in each calculation (Tvent, TLac and Dmax) was foreseen to add a range of threshold powers and therefore enhance the likelihood of a possible match. The computation of Tvent, TLac and Dmax is shown in the data reduction section below. For statistical reasons, the null hypothesis was that no significant differences (p > 0.05) would be detected between the load at cFTP and TLac, Dmax and/or Tvent. Where the null hypothesis was accepted, agreement between tests was assessed using statistical measures of reliability and reproducibility.

METHODS

Participants

The current study obtained ethical approval from the Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee in Trinity College Dublin and was performed in accordance the ethics standards of the International Journal of Exercise Science (16). Participants completed a consent form prior to beginning any trials. Nineteen (12 male, 7 female) highly-trained cyclists and triathletes, mean age 28-yr (± 6) participated. The mean VO2peak, body mass, body mass index (BMI) and % body fat of enlisted participants are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean (± SD) VO2peak, mass, BMI and % body fat data for participants.

| GxT VO2peak (mL·kg−1·min−1) | VO2peak FTP (mL·kg−1·min−1) | Mass (kg) | BMI (kg·m−2) | Body fat (%) | Age (yr) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 59.3 ± 6.9 | 57.2 ± 3.3 | 57.0 ± 4.1 | 20.1 ± 1.2 | 16.3 ± 1.4 | 28 ± 6 |

| Male | 66.3 ± 5.5 | 65.1 ± 5.5 | 66.1 ± 4.9 | 22.0 ± 1.0 | 10.5 ± 1.3 | 28 ± 7 |

(SD) – standard deviation, (BMI) – Body mass index, (GxT VO2peak) – Peak maximum oxygen uptake during graded incremental test, (VO2peak FTP) – peak maximum oxygen uptake during functional threshold power test, (mL·kg−1·min−1) -milliliter of Oxygen consumed per kilogram body mass per minute, (kg) – kilogram, (kg·m−2) – kilogram divided by meter squared, (yr) – year.

Protocol

Participants attended the laboratory on four occasions, in a rested, carbohydrate loaded and well-hydrated state, having abstained from alcohol and caffeine in the 24-h prior to testing. Trials were separated by a minimum of 6 and maximum of 10-day. Training load was agreed with both athletes and coaches prior to commencing the study, with weekly training load and stimulus remaining as constant as possible for the testing period. Exercise was limited to aerobic work for 48-h prior to each test. A 24-h food diary was completed prior to the first trial. A copy of the food diary was retained by both the researcher and the participant. Each participant was requested to replicate their food intake prior to all tests, or if different, to consume comparable carbohydrate quantities. When necessary, participants were helped to plan their meals. Pre-test hydration status was assessed as urine specific gravity (USG) by refractometry (Bellingham & Stanley, Kent, UK) prior to all tests, euhydration was defined as USG < 1.020. In addition, a full blood count was performed to screen for sub-clinical anaemia and infection.

Visit one involved a detailed medical assessment and a 3-min graded incremental test (GxT) to volitional exhaustion. Participants completed a 10-min warm-up on an air-braked cycle ergometer (WattBike, Nottingham, UK) below the initial power output required for the GxT (female < 90 W, male < 120 W). This time interval allowed participants to make minor adjustments to their cycling position (saddle height and fore-aft position, handlebar height and reach); these individual positions were noted and replicated during subsequent visits. The increments for the female and male cohort were 20 and 25 W, respectively, and cadence was controlled between 75 and 110 rev·min−1. Finger-tip capillary blood samples for lactate analysis were collected at 2-min into each 3-min increment and assessed using a calibrated YSI 1500 Sports Lactate analyzer (YSI, OH, USA). Breath-by-breath ventilatory (VE, VO2 and VCO2) and heart rate (HR) data, recorded using a calibrated cardio-metabolic cart (CPET; Cosmed, Rome, Italy), were averaged across the final minute of each increment. Each participant’s VO2peak was determined as the highest consecutive five breath average during the final test increment.

All participants had previously completed an FTP test prior to participation in the current study. During visits two and three, 20-min FTP tests were completed in the laboratory and projected 60-min FTP (cFTP) was computed (cFTP = 95% of the 20-min trial). Five participants were available for 3 visits only due to race commitments; therefore, they completed the GxT, one 20-min FTP test and the 60-min cFTP test. Data for these five participants were omitted from all analyses pertaining to test-retest reliability and repeatability. However, their data were included in the assessment of the validity of the assertion that cFTP could be sustained in a quasi-steady state for 60-min. Endeavoring to adhere as closely as possible to the construct of the FTP warm-up, the first FTP test warm-up used 65% Dmax as a proxy for 65% cFTP, the 5-min time-trial effort during the second FTP test was controlled at the same power attained during the initial FTP test and cadence during the warm-up was un-controlled. Table 3 outlines the timelines for capillary blood sample collection and measurement of ventilatory variables during all test sessions.

Table 3.

Time intervals during tests when BLa and ventilatory data were measured.

| Test | Lactate sample | Ventilatory data |

|---|---|---|

| GxT | 2-min into each workload | Continuously |

| FTP1 and FTP2 | Post 5-min time-trial | From 31 to 66-min |

| Pre 20-min time-trial | ||

| Post 20-min time-trial | ||

| 60-min at cFTP | 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 and 60-min | Start (0 to 10-min) |

| End (50 to 60-min) |

(BLa) – Blood lactate, (GxT) - graded incremental test, (FTP) – functional threshold power, (min) - minute

During visit four, participants (n = 19) were tasked with sustaining their cFTP power for 60-min. The pre-test warm-up was standardized as 7-min at 55% of Dmax, 5-min at 65% of Dmax, 3-min at cFTP and 3-min stationary rest. On-line VO2 and HR data were recorded during the 60-min cFTP test at the start and end (0 to 10 and 50 to 60-min). The facemask was removed from 11 to 49-min to facilitate participants drinking carbohydrate beverage ad libitum. Participants were asked to bring their normal race beverage, with the only stipulation being that the drink contained carbohydrate. Fingertip capillary blood samples were collected for lactate analysis at 10-min intervals throughout the 60-min trial, see Table 3.

Threshold loads (W) for Tvent, TLac and Dmax were determined from the recorded GxT data. VO2 was used as the dependent variable; the associated power output was used to estimate Tvent and Dmax (4). Load at Tvent data were identified using a segmented regression model minimizing the squared sum of the residuals following logarithmic transformation of VO2 and load data (SigmaPlot 13.0; Systat, IL, USA). Load at TLac and Dmax was identified using “Lactate E” software (17). The line of best fit for the Dmax calculation is calculated using third order curvilinear regression using VO2 and BLa data at each workload. Thereafter, the maximum perpendicular distance to the straight line between the lowest and highest BLa data identified load at Dmax (4). The calculation of TLac is accomplished using a linear spline minimizing the sum of the squared differences between workload and BLa, the workload preceding a departure from the straight line is identified as TLac (12). A single factor repeated measures ANOVA, quantified using post-hoc Bonferroni tests with p < 0.05 inferring significance, compared threshold data and was used to cull variables on the basis of there being a statistically significant difference compared to cFTP (2).

Statistical Analysis

An a priori power test was conducted for expected outcomes with a Type 1 error probability of 0.05, a power of 0.85 and a projected effect size 0.3. This analysis indicated that n = 19 would provide a statistical power of 85% (G*Power v3.0.10 free software; Institute of Experimental Psychology, Heinrich Heine University, Dusseldorf, Germany). All data were checked for normality using both the D’Agostino and Pearson, and the Shapiro-Wilk tests. The reliability of the FTP test was assessed using intra-class correlation (ICC), standard deviation of the residuals (Sy.x), coefficient of determination (r2) and computing 95% confidence intervals of r (95% CI). The reproducibility of the FTP test was assessed using relative technical error of the measure (% TEM) and Bland Altman 95% limits of agreement (95% LoA). These analyses were performed using Prism 7 (Graph Pad, CA, USA).

Group data are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). VO2 measured during the 60-min trial was classified as steady-state if it remained significantly lower (p < 0.05, paired Student’s T test) than VO2peak, a specific demarcation used in identifying critical power (CP), a metric described as the boundary between steady- and non-steady-state cycling (26). Steady-state BLa data were assessed using maximal lactate steady state (MLSS) criteria, that is, an increase in BLa < 0.05 mmol·L−1·min−1 (8). We hypothesized that peak 60-min BLa would be significantly (p < 0.05) lower than GxT peak BLa. This might be sufficient to affirm Allen and Coggan’s (1) assertion that cFTP elicits a steady-state VO2 response. However, this would not elucidate whether the intensity was the upper-limit intensity. MLSS can be identified using increases of 0.2 W·kg−1 until the load destabilized BLa data (19). The difference in power output between the 20-min time-trial and cFTP was 5%. Consequently, we reasoned that if the 5% difference in power equated to ≤ 0.2 W·kg−1 and marked the boundary between steady and non-steady state, then the 60-min FTP power was the upper limit of steady-state.

For the purpose of comparing cFTP data with alternate threshold tests, acceptable 95% LoA were set as ± 20 W. These LoA were considered appropriate for clinical use (2); namely, to discern biological change whilst mitigating against the risk of erroneous or misleading results. “Performance VO2” was calculated by expressing VO2 data during the 60-min test at cFTP as a percent of VO2peak (5). During the 60-min test, HR data were recorded during the initial and final 10-min of exercise, individual changes in mean HR data are reported. Peak HR measures were assessed for significant differences (p < 0.05, paired Student’s T test) with GxT HR maxima.

RESULTS

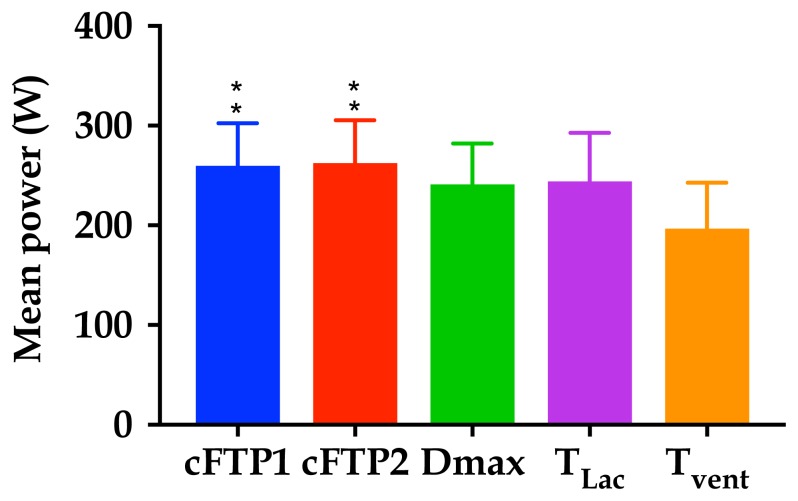

ANOVA identified no significant (p > 0.05) difference in power output between cFTP (259 ± 40 W) and Dmax or TLac (246 ± 38 and 244 ± 47 W, respectively). However, the load at Tvent (197 ± 43 W) was significantly lower (p < 0.01) than cFTP, consequently, Tvent data were excluded from further data analysis, see Figure 1. Mean group and gender specific power, normalized to body mass (W·kg−1), at Dmax, TLac, cFTP and last completed GxT stage (peak GxT) are listed in Table 4. The 95% LoA, the mean bias, r2, Sy.x and 95% CI associated with; cFTP1 vs. cFTP2, cFTP vs. Dmax and cFTP vs. TLac are detailed in Table 5.

Figure 1.

Bar graph of load at computed thresholds, bars denote SD, n = 15. Asterisk symbol (*) infers significantly higher than Tvent, ** infers p < 0.01.

Table 4.

Mean power (W·kg−1) associated with load at Dmax, TLac, cFTP and peak GxT load. Columns indicate the whole population sample, female only and male only.

| Group | Female | Male | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dmax (W·kg−1) | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.4 |

| TLac (W·kg−1) | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.6 |

| cFTP (W·kg−1) | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 4.1 ± 0.5 |

| Peak GxT (W·kg−1) | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 5.0 ± 0.4 |

(W·kg−1) – Watt per kilogram of body mass, (Dmax) – Load at maximum displacement, (TLac) – Lactate threshold, (cFTP) – Functional threshold power, (GxT) – graded incremental test.

Table 5.

Results of comparisons for cFTP, Dmax and TLac computing % TEM, ICC, r2 and 95% CI.

| cFTP1 vs. cFTP2 | cFTP vs. Dmax | cFTP vs. TLac | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 95% LoA (W) | + 13 to −17 | + 43 to − 7 | + 68 to − 37 |

| Mean bias (W) | −2 | 18 | 16 |

| % TEM | 2.3 | 7.1 | 8.5 |

| ICC | 0.980 | 0.832 | 0.791 |

| r2 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 0.64 |

| 95% CI | 0.87 to 1.11 | 0.72 to 1.10 | 0.51 to 1.33 |

| Sy.x (W) | 9 | 14 | 30 |

(cFTP) – Functional threshold power, (Dmax) – Load at maximum displacement, (TLac) – Lactate threshold, (% TEM) – Relative technical error of measurement, (ICC) - Inter-class correlation coefficient, (r2) – Coefficient of determination, (CI) – confidence interval, (LoA) – limits of agreement, (Sy.x) – Standard deviation of the residuals, (W) – Watt.

No significant difference (p > 0.05) was detected comparing GxT peak BLa data with 20-min FTP BLa maxima (6.9 ± 1.3 vs. 6.9 ± 1.9 mmol·L−1, respectively). However, peak BLa data were significantly lower (p < 0.05) during the 60-min cFTP test than peak GxT BLa (4.0 ± 1.1 vs. 6.9 ± 1.3 mmol·L−1, respectively). During the 60-min test, mean HR after 10-min at cFTP (158 ± 14 beats·min−1) increased across time by 9% (14 ± 7 beats·min−1), however, mean HR between 50 and 60-min at cFTP remained significantly (p < 0.05) lower (178 ± 11 beats·min−1) than peak HR data recorded during the GxT (186 ± 12 beats·min−1). In addition, mean VO2 data increased by 6% from start to end of the cFTP test (52.0 ± 6.4 vs. 55.0 ± 5.7 mL·kg−1·min−1, respectively), but similarly to HR data, remained significantly (p < 0.05) lower than peak GxT data (62.9 ± 6.2 mL·kg−1·min−1). The 5% power output difference between the 20 and 60-min trials equated to an average of 0.19 ± 0.02 W·kg−1. “Performance VO2” increased from 84% at 10-min to 88% of VO2peak during the last 10-min of the 60-min cFTP trial.

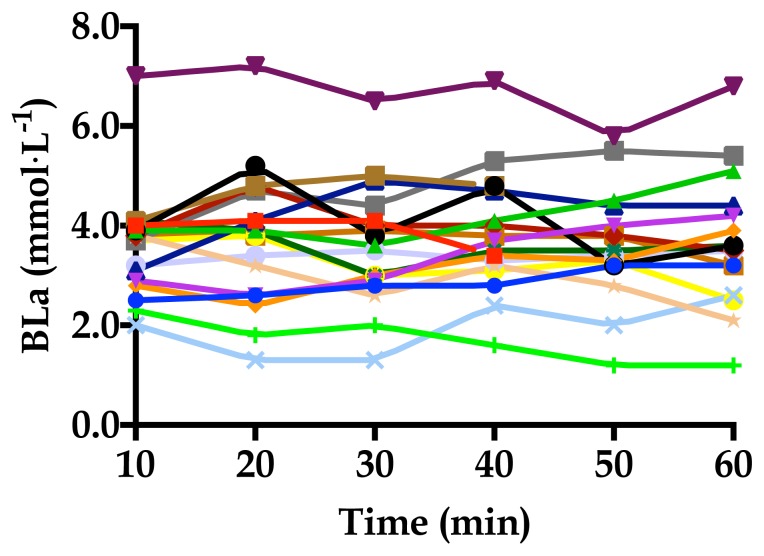

In the current study, individual power at cFTP was sustained for 60-min by seventeen (89 %) of nineteen athletes assessed; the two athletes unable to complete the cFTP trial aborted at 35 and 52-min, respectively. Analysis of their BLa kinetics from 10 to 60-min indicated that the rate of change in BLa data from 10-min onwards remained below 0.05 mmol.L−1.min−1 (Figure 2). The two athletes that could not complete the 60-min trial had their BLa data assessed at test termination. Neither participant’s BLa had increased by > 0.05 mmol·L−1·min−1 upon termination. As the facemask was removed to facilitate drinking, determination as to whether their VO2 was also in a steady-state was not possible. Individual BLa data measured at 10-min intervals during the 60-min trial at cFTP are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Individual BLa data at 10-min intervals during the 60-min trial at cFTP (n = 19).

DISCUSSION

The results of the current study demonstrate that FTP is a reliable test. Both ICC and r2 were high, while the corresponding residuals had a low standard deviation (ICC = 0.98 r2 = 0.96, Sy.x = 9 W). The FTP test was also found to be repeatable with satisfactory limits of agreement (+13 to −17 W; mean bias −2 W) and a low relative TEM of 2.3%. Consequently, the reliability and repeatability of the FTP test supports the inclusion of the 5 participants who completed a single FTP prior to the validity trial.

The FTP test was shown to identify a cycling power output that could be sustained for 1-hour in seventeen of nineteen (89%) athletes. Participants were asked to stop cycling after 1-hr as this met the criteria specified as FTP (1). The purpose of the trial was not to determine a time to exhaustion. This eliminates the establishment of an absolute 60-min limit of tolerance. However, the FTP test itself provides a 20-min limit of tolerance, supporting the contention that 60-min maximum power is < 5 % above cFTP. Of note, this study group were highly trained, mean fraction of VO2max sustained during the 60-min trial was 84 % (using the first 10-min rather than the last 10-min VO2 data as the numerator), a fraction reflective of elite endurance athletes (8). The high sustained fraction of VO2 at cFTP is particularly relevant if percentages of FTP are used to formulate exercise prescription, as currently recommended (1). Were a trained and untrained cyclist to train at the same percentage of their FTP, each would likely be cycling at different percentages of absolute maximum 60-min power. In the context of training at percentages of maximum, overtraining and / or a poor response to training zones has previously been described (18). The cause of volition exhaustion appears beyond the scope of this investigation. The two unsuccessful participants were euhydrated, reportedly carbohydrate loaded and adhered to all pre-trial exercise controls. The two participants also met the definitions of steady state BLa. As a consequence of the face mask being removed to allow drinking, it cannot be discerned whether VO2 was steady state on cessation. However, both participants maintained steady-state VO2 for in excess of 30-min. Both cyclists were observed to be under a lot of stress on volitional exhaustion and consequently motivation did not appear to be the limiting factor. These investigators would recommend future research include an examination of the reliability of the 60-min trial. Additionally, future research into the trained state of the cyclist may prove insightful. The distinction between an index for a 35-min versus a 60-min limit of tolerance is worth considering. In the context of exercise prescription, where the ideal intensity is to be steady-state, one might suggest the FTP metric adequate.

Strategies taken from investigations into MLSS and CP were used to measure whether quasi-steady state VO2 and BLa data were attained, not to expound whether FTP was interchangeable with MLSS or CP. The BLa and VO2 responses in this investigation support the concept of a steady state being reached at cFTP. Furthermore, the ≤ 0.2 W·kg−1 increment required to destabilize BLa and VO2 support the claim that cFTP was the uppermost intensity whereby a quasi-steady state could be maintained.

The strength of the relationship between cFTP and Dmax was stronger than the relationship between cFTP and TLac (r2 = 0.89, Sy.x = 14 W, 95% CI = 0.72 to 1.10 vs. r2 = 0.73, Sy.x = 26 W, 95% CI = 0.64 to 1.38, respectively). Nonetheless, the LoA associated with cFTP and Dmax were greater (+ 43 to − 7 W) than the LoA set a priori (+20 to −20 W). As such, we recommend that cFTP should not be used interchangeably with Dmax or TLac. Dmax and TLac are commonly used to determine physiological thresholds, but do not have associated limits of tolerance; namely, a defined upper limit duration (time) associated with a specific power output. This potentially highlights another likely function for the FTP test. A uniform racing pace tactic has been reported to be the fastest strategy where terrain is even, conditions still and duration extensive (7). Under these circumstances, cFTP is most likely a superior index to TLac or Dmax as a uniform power output pacing strategy is possible, unlike pacing using physiological indices, which are susceptible at some level to temporal changes (9).

An investigation into the interchangeability of cFTP with CP may be worthwhile. CP “is mathematically defined as the power-asymptote of the hyperbolic relationship between power output and time to exhaustion” (26). However, of note, CP is reported sustainable for < 30-min (22), although this disparity may be explained in part by the untrained status of the participants in investigations (21). The landmark paper by Monod and Scherrer (13) stated that exercise at CP could be sustained indefinitely, although the context was in respect to local muscle work, illustrated as being equivalent to “one leg” exercises, independent of respiratory and cardiovascular factors. The determination of CP also furnishes a metric named W′ which represents the fixed amount of work that can be performed above CP (21). The energy provided by W′ is likely to include anaerobic substrates and energy derived from oxygen stores, although, the exact physiological underpinnings of W′ are unknown (22). Were CP and cFTP are found to be interchangeable, one might posit that the difference between quasi-steady state (cFTP) and maximum power to be correlated with the size of W′. The FTP test has been appraised elsewhere, whereby participants were tasked with completing a 60-min time-trial as fast as possible, and the mean power achieved said to reflect cFTP (3). This methodology appears to consider cFTP as the maximum intensity a participant can maintain, rather than that of a quasi-steady state. Vanhatalo et al. (26) categorized a W′ of 25 kJ as “large”, however, extrapolated across a 1-h period a W′ of 25 kJ equates to 7 W, this is equivalent to a 2.3 % increase in power above cFTP for an elite rider weighing 60-kg with a cFTP of 5 W·kg−1. The reproducibility in common performance cycling tests is typically 2 to 3% (11) and meaningful change in elite sport is suggested as being approximately 0.4 to 1.5 % (11, 23). The practical and or experimental significance of a 2.3% differential between cFTP and maximum power should perhaps be considered in the context of the purpose of the test.

The current investigation used the upper-limit of BLa change in MLSS to establish a tenet criteria to assess the claim that cFTP was a quasi-steady state intensity. Currently, there is a scarcity of peer-reviewed investigations into FTP. A single investigation into the interchangeability of FTP and MLSS reported “trivial” differences between cFTP and MLSS (3). The associated LoA in “well trained” and “trained” populations (11.8 and 6.4 %, respectively) were reported in percentage format (3). The determination of absolute differences (W) versus percentages of differences likely requires deliberation, as a higher cFTP would result in larger absolute LoA.

Researchers have indicated that maximum sustainable power can only be achieved with the concession of aerodynamic position (6, 19, 25). If the FTP test data were derived from a power maximized position, consideration would need to be given when applying cFTP to a less powerful drag-optimized position. Beyond the cycling position adopted by the cyclist, part of our reluctance to appraise FTP in the field was that the average power might be affected negatively by the topography of the testing environment. Allen and Coggan (1) introduce a non-validated algorithm termed “normalized power” (NP), which purportedly overcomes underestimates of mean power as a consequence of stochastic cycling. If validated, this weighted average could potentially facilitate the appraisal of the FTP test in the field. To compute NP the power data are smoothed using a 30-s moving average, raised to the fourth power, averaged over time and lastly the fourth root computed (10). The adopted pacing strategy in the Borszcz et al. (3) investigation was open and variable. This strategy is very clear but may overlook the negating effect of a variable versus a uniform pacing strategy (7). The current study required position and power output to be held constant, and as such, our findings only reflect similar pacing strategies and conditions. Our focus was to determine whether it was possible physiologically to maintain FTP power for 60-min rather than to factor in “all” pacing strategies and / or positions.

In conclusion, the FTP test was shown to be a reliable and repeatable test. The current investigation demonstrated that the FTP test successfully determined 60-min power in 89% of assessed participants and prompted a quasi-steady state BLa and VO2 in all assessed participants. These findings are however limited to a similarly highly trained, highly motivated cohort. Extrapolation to lesser-trained groups would require fresh investigation. The findings herein support the utility of FTP as part of a pacing strategy in competition. Proceeding forwards, it appears that research into the interchangeability of FTP with MLSS and or CP may be worthwhile. In the instance that these tests were found interchangeable with FTP, the benefits would include more affordable and less time-consuming testing. Noteworthy, the disadvantages of using the FTP test in lieu of physiological data is the lack of insight as to where performance gains might be made. A performance is the sum of whole-body energetics that does not provide information such as fuel use, efficiency, aerobic versus anaerobic capacity. The principle limitation of the current study is that FTP was not assessed outside; where for the most part the majority of cycling is performed. However, the current investigation provides a starting point for further ecological assessment, given the demonstrated efficacy of the test. Inevitably, as Morton stated, “the single most remarkable conclusion is on the one hand such a plethora of models fit the real world so well, yet there is so much more to discover” (14).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest or financial arrangements related to this research. We would like to thank all athletes for their gracious participation in this research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen H, Coggan A. Training and racing with a power meter. VeloPress; CO, USA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bland J, Altman D. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;8:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borszcz F, Tramontin A, Costa V. Is the functional threshold power interchangeable with the maximal lactate steady state in trained cyclists? Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2019 doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2018-0572. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng B, Kuipers H, Snyder A, Keizer H, Jeukendrup A, Hesselink M. A new approach for the determination of ventilatory and lactate thresholds. Int J Sports Med. 1992;13:518–522. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costill D. Metabolic responses during distance running. J Appl Physiol. 1970;28:251–255. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1970.28.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fintelman D, Sterling M, Hemida H, Li F-X. Optimal cycling time-trial position models; aerodynamics versus power output and metabolic energy. J Biomech. 2014;47:1894–1898. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukuba Y, Whipp B. A metabolic limit on the ability to make up for lost time in endurance events. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:853–861. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.2.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heck H, Mader G, Hess G, Mucke S, Muller R, Hollmann W. Justification of the 4-mmol·L−1 lactate threshold. Int J Sports Med. 1985;6:117–130. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1025824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeukendrup A, van Diemen A. Heart rate monitoring during training and competition in cyclists. J Sports Sci. 1988;16:S91–S99. doi: 10.1080/026404198366722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jobson S, Passfield L, Atkinson G, Barton G, Scarf P. The Analysis and Utilization of Cycling Training Data. Sports Med. 2009;39:833–844. doi: 10.2165/11317840-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamberts R, Swart J, Woolrich R, Noakes T, Lambert M. Measurement error associated with performance testing in well-trained cyclists: Application to the precision of monitoring changes in training status. Int Sports Med J. 2009;10:33–44. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lundberg M, Hughson R, Weisiger K, Jones R, Swanson G. Computerised estimation of lactate threshold. Comput Biomed Res. 1986;19:481–486. doi: 10.1016/0010-4809(86)90042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monod H, Sherrer J. The work capacity of a synergic muscular group. Ergonomics. 1965;8:329–338. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morton R. The critical power and related whole-body bioenergetic models. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006;96:339–354. doi: 10.1007/s00421-005-0088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naimark A, Wasserman K, McIlroy M. Continuous measurement of ventilatory exchange ratio during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1964;19:644–652. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1964.19.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Navalta J, Stone W, Lyons T. Ethical issues relating to scientific discovery in exercise science. Int J Exerc Sci. 2019;12:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newell J, Higgins D, Madden N, Cruickshank J, Einbeck J, Mc Millan K, Mc Donald R. Software for calculating blood lactate endurance markers. J Sports Sci. 2007;25:1403–1409. doi: 10.1080/02640410601128922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olbrecht J. Planning, periodizing and optimizing swim training. F & G Partners; Belgium: 2007. The science of winning; pp. 115–117. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Padilla S, Mujika I, Angulo F, Goirene J. Scientific approach to the 1-h cycling world record: A case study. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:1522–1527. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.4.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palleres J, Moran-Navarro R, Ortega J, Fernandez-Elias V, Mora-Rodriguez R. Validity and reliability of ventilatory and blood lactate thresholds in well-trained cyclists. PLoS ONE. 11:e0163389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poole D, Ward S, Garner G, Whipp B. Metabolic and respiratory profile of the upper limit for prolonged exercise in man. Ergonomics. 1988;31:1265–1279. doi: 10.1080/00140138808966766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poole D, Burnley M, Vanhatalo A, Rossiter H, Jones A. Critical power: An important fatigue threshold in exercise physiology. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48:2320–2334. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pyne D. Physiological tests for elite athletes. Second edition. Australian Institute of Sport Human Kinetics; Champaign, IL, USA: pp. 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stockhausen W, Grathwohl D, Burklin C, Spranz P, Keul J. Stage duration and increase of work load in incremental testing on a cycle ergometer. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1997;76:295–301. doi: 10.1007/s004210050251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Underwood L, Schumacher J, Burette-Pommay J, Jermy M. Aerodynamic drag and biomechanical power of a track cyclist as a function of shoulder and torso angles. Sports Eng. 2011;14:147–154. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vanhatalo A, Jones A, Burnley M. Application of critical power in sport. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2011;6:128–136. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.6.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]