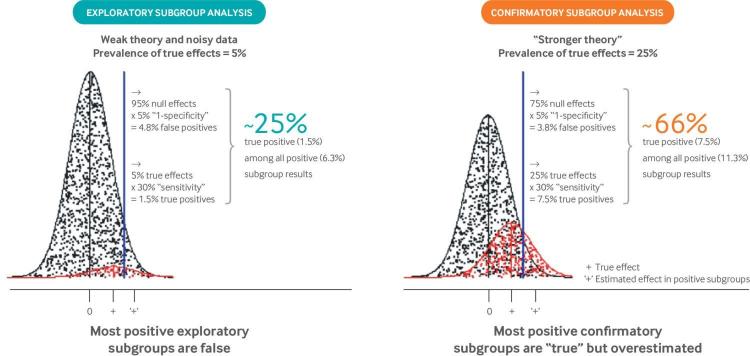

Fig 2.

Why most positive subgroup effects are false or overestimated. The well known unreliability of subgroup analysis arises from the fact that interaction tests typically have weak power when performed in randomized clinical trials designed to have 80% or 90% power to detect main treatment effects, and also by the fact that multiple poorly motivated subgroups are typically evaluated.48 “Exploratory” analyses are depicted by the distributions on the left, in which subgroup analyses are undertaken across multiple variables to detect the 5% that represent true effect modification (shown in red). This prevalence of “true effects” was chosen to emulate previous meta-epidemiologic studies.42 Assuming 30% power to detect interaction effects,38 47 only a minority of these true effects (1.5/5=30%) are anticipated to show statistically significant effects. Meanwhile, with an α of 0.05 (P value threshold), 5% of the null variables (shown in black) are also anticipated to be statistically significant (5/95=4.8%). Thus, only a minority of results with a P value <0.05 (1.5/6.3 of the effect estimates falling to the right of the blue threshold) represent true subgroup effects. The false discovery rate is much lower when only variables with a higher prior probability are tested. The distribution on the right depicts “confirmatory” analyses with a prior probability of 25%. Here, about two thirds of subgroups with a P value <0.05 (7.5/11.3) are anticipated to represent true effects. Even then, subgroup effects will generally be overestimated because exaggerated effects are preferentially identified. This exaggeration of effects has been referred to as “testimation bias” because it arises when hypothesis testing statistical approaches (eg, for biomarker discovery) are combined with effect estimation.49