Abstract

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is sensed by cells and can trigger signals to modify gene expression in different tissues leading to changes in organismal functions. Despite accumulating evidence that several pathways in various organisms are responsive to CO2 elevation (hypercapnia), it has yet to be elucidated how hypercapnia activates genes and signaling pathways, or whether they interact, are integrated, or are conserved across species. Here, we performed a large-scale transcriptomic study to explore the interaction/integration/conservation of hypercapnia-induced genomic responses in mammals (mice and humans) as well as invertebrates (Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster). We found that hypercapnia activated genes that regulate Wnt signaling in mouse lungs and skeletal muscles in vivo and in several cell lines of different tissue origin. Hypercapnia-responsive Wnt pathway homologues were similarly observed in secondary analysis of available transcriptomic datasets of hypercapnia in a human bronchial cell line, flies and nematodes. Our data suggest the evolutionarily conserved role of high CO2 in regulating Wnt pathway genes.

Subject terms: Evolutionary genetics, Gene regulation

Introduction

Cells and tissues sense and respond to changes in concentration of gaseous molecules through evolutionarily conserved pathways. Oxygen- and nitric oxide-activated cellular signaling pathways are well described1,2, but much less is known about the mechanisms by which non-excitable cells sense and respond to changes in carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations3,4. In humans, an increase in CO2 levels (hypercapnia) is a consequence of inadequate alveolar gas exchange in patients with lung diseases such as the acute respiratory distress syndrome5,6, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease7 and others4,8. Although initially thought to be benign or even protective5,6, it is becoming increasingly evident that hypercapnia has significant pathophysiological effects that may be deleterious to organs such as the lung7–10 and skeletal muscles11. Recent discoveries suggest that elevation of CO2 activates specific signal transduction pathways with adverse consequences for cellular and organismal functions not only in mammals7,9,12–14, but also fish15, fly Drosophila melanogaster16,17, and nematode Caenorhabditis elegans17,18. Hypercapnia has also been reported to alter gene expression in different tissues, cells and species7,12,16,18,19. However, a systems-level understanding of elevated CO2 effects and of how they are integrated into signaling pathway network, and whether hypercapnia-induced gene programs are similar in different tissues/cells and species is not completely understood.

Here, we performed a large-scale comparative transcriptomic study to explore the interaction/integration/conservation of hypercapnia-responsive genes combining multi-tissue microarray analysis in mice with secondary analysis of transcriptomic datasets of hypercapnia in human bronchial epithelial cells (HBEC)12, Drosophila melanogaster16 and Caenorhabditis elegans18. We found that hypercapnia activates genes that regulate Wnt signaling in mouse cells, lungs and skeletal muscles. Hypercapnia-activated Wnt pathway homologues were similarly observed in the human bronchial cells, flies and nematodes at gene expression level. Our data suggest that the role of high CO2 as a gaso-signal in regulating Wnt signaling pathways is evolutionarily conserved.

Results

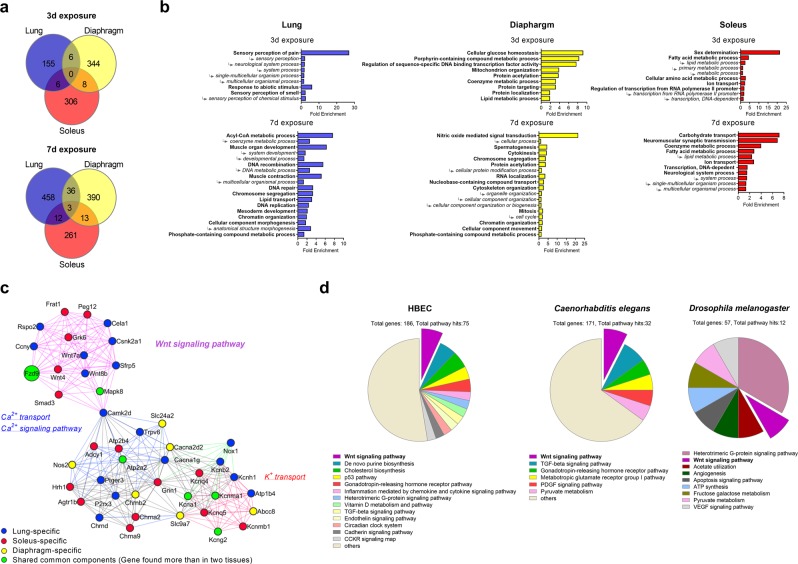

Multi-tissue microarray analysis identifies functional similarity in gene networks across different mouse tissues exposed to normoxic hypercapnia

In mammals, lung diseases are associated with suboptimal function of other metabolic organs including skeletal muscle20. To elucidate whether hypercapnia activates conserved genes or gene networks governing specific signaling pathways on an organismal level, we performed a multi-tissue microarray analysis, contrasting available transcriptomic datasets in mouse lungs7 with microarray analysis of skeletal muscles, diaphragm and soleus, isolated from mice exposed to normoxic hypercapnia (60 to 80 mmHg = 10% CO2 and 21% O2) or sea-level room air for up to 7 days (Fig. 1). The microarray analysis in the lungs, as compared to the skeletal muscles, revealed increased number of differentially expressed genes (DEG) dependent on CO2 exposure time (Fig. 1a), suggesting that the transcriptional response differs in terms of genes regulated and/or the kinetics of gene activation among the different tissues. Although up-regulated hypercapnia-responsive gene sets differed among the tissues, we found three genes of which was robustly represented in all the tissues, Fzd9, Gm7120 and LOC100044171, at 7-day exposure conditions (Fig. 1a and Table S1). We next examined effects of hypercapnia on the functional categorization of the DEG in the tissues. A biological process analysis of the DEG was performed by the Protein ANalysis THrough Evolutionary Relationships (PANTHER) classification system (Fig. 1b). A network diagram constructed from the DEG at 7-day exposure conditions revealed groups of genes and pathways that shared common components (green circles) but was also comprised of lung-specific, diaphragm-specific, soleus-specific response to hypercapnic exposure (Fig. 1c, blue, yellow and red circles, respectively). Despite differences of gene signatures in biological processes observed among the tissues, an unbiased functional analysis of hypercapnia-responsive genes showed that the impact of hypercapnia on gene expression was highly similar. We found three functionally conserved gene networks in response to hypercapnia; Wnt signaling pathway, calcium ion (Ca2+) transport/signaling pathway and potassium ion (K+) transport (Fig. 1c). To identify transcription factors potentially regulatory for the hypercapnia-responsive genes and conserved in different tissues, we further analyzed our microarray data using an inference transcription factor analysis (Fig. S1). We identified several transcription factors regulatory for hypercapnia-responsive genes, as inferred from differential gene expression signatures of day-3, day-7, or both, hypercapnia responses.

Figure 1.

A large-scale transcriptomic study of hypercapnia to combine mouse multi-tissue microarray analysis with secondary analysis of available transcriptomic datasets. (a–c) C57BL/6 J mice were exposed to normoxic hypercapnia for 3 (n = 4) or 7 (n = 3) days or maintained in sea-level room air (n = 3). (a) Venn diagrams showing the overlap between DEG from lung, diaphragm and soleus. (b) Gene ontology analysis of the DEG in each tissue using the PANTHER GO-Slim Biological Process annotation dataset. Arrows indicate hierarchical grouping between GO terms. (c) A network diagram constructed from the DEG in each dataset at 7-day exposure conditions. The network diagram revealed groups of genes and pathways that shared common components (green circles) but was also comprised of lung-specific, diaphragm-specific, soleus-specific responsive to hypercapnic exposure (blue, yellow and red circles, respectively). (d) Secondary analysis of transcriptomic datasets of hypercapnia in HBEC, Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster. PANTHER classification system categorized the DEG in each dataset into signaling pathways.

Analysis of transcriptomic datasets of hypercapnia in a human bronchial cell line and invertebrates

We next compared mouse hypercapnia gene signatures against transcriptomic datasets of normoxic hypercapnia in HBEC12, Caenorhabditis elegans18 and Drosophila melanogaster16. We need to mention that high CO2 exposure conditions in each dataset were somewhat different; 20% CO2 exposure for 24 hours in HBEC, 19% CO2 for 72 hours in Caenorhabditis elegans and 13% CO2 for 24 hours in Drosophila melanogaster. The PANTHER classification system categorized DEG into signaling pathways in each dataset. Despite different conditions of high CO2 exposure in each dataset, we found the DEG involved in Wnt signaling pathway overrepresented in the human bronchial cell line and invertebrates (Fig. 1d). Multiple gene components of the Wnt pathway were also detected in the DEG of mice, HBEC and invertebrates during hypercapnia (Fig. S2 and Table S2). These data suggest that the genes involved in the Wnt pathway are the highest prevalence group of hypercapnia-responsive genes that may be conserved across the tissues and organisms.

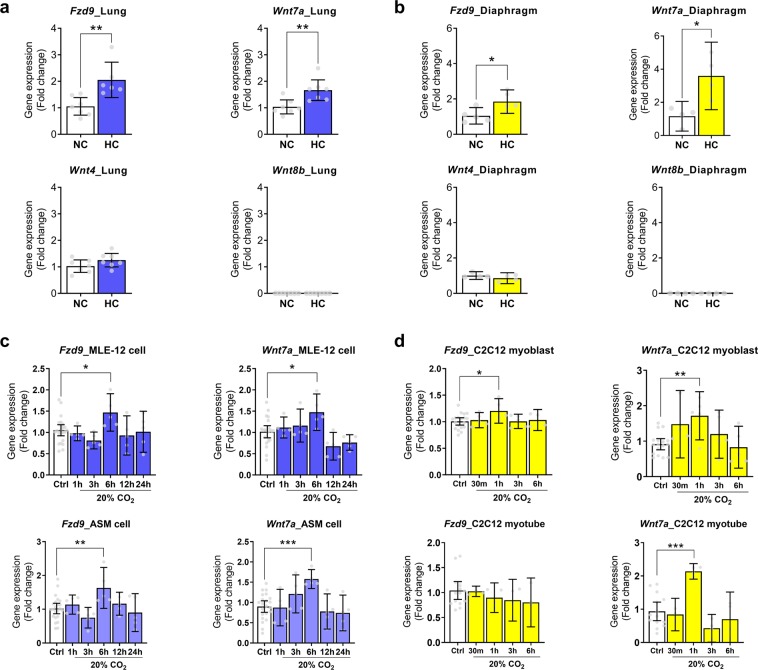

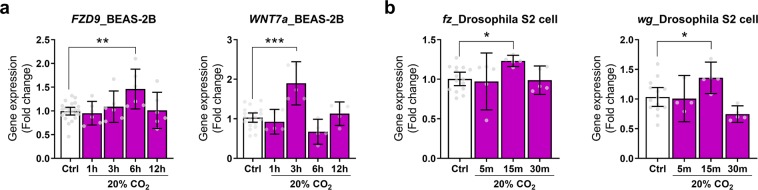

Validation of conserved Wnt pathway genes in the large-scale microarray analysis

To validate of our large-scale microarray data, quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using RNA isolated from different mouse tissues (lung and diaphragm skeletal muscle) and cells exposed to high CO2 conditions (Fig. 2). For in vivo experiments, we examined expressions of Fzd9, Wnt4, Wnt7a and Wnt8b for the gene network of “Wnt signaling pathway” (Fig. 2a,b). The relative expression levels of Fzd9 and Wnt7a exhibited the same regulatory trends as compared with the microarray analysis, suggesting that hypercapnia activates genes that regulate the Wnt signaling in mice tissues. We next examined expressions of genes validated in the tissues, Fzd9 and Wnt7a, in a panel of mouse cell types; mouse lung epithelial (MLE)-12 cells representing as an epithelial lineage, airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells as the smooth muscle cell lineage and C2C12 myoblasts and myotubes as skeletal muscle lineage exposed to high (~120 mmHg = 20%) CO2 and normoxia with an extracellular pH of 7.4. These cell lineages are one of the major cell components of the lung or skeletal muscle tissues and have been reported to show signal transduction pathways and the related-biological effects of hypercapnia as previously reported7,9,11. Fzd9 and Wnt7a expressions were tightly regulated and peaked at six hours after high CO2 exposure in the lung cells, and at one hour in the skeletal muscle cells but not in the myotubes (Fig. 2c,d). We also examined expression of FZD9 and WNT7a in an immortalized human bronchial epithelial cell line BEAS-2B (Fig. 3a) and major Frizzled and Wnt ligand genes (fz and wg) in Drosophila S2 cells (macrophage like lineage) (Fig. 3b). Consistent with the data in mouse cells, hypercapnia caused transient increases in particular in Frizzled and WNT ligand gene expressions in the human and fly cells. Taken together, our data suggest that normoxic hypercapnia activates genes that regulate the Wnt signaling pathway across different cells, tissues and species.

Figure 2.

Validation of mouse multi-tissue microarray analysis. (a,b) Validation in mouse tissues. Fzd9, Wnt4, Wnt7a, and Wnt8b expression in the lung (n = 6–7) (a) and diaphragm skeletal muscle (n = 4–5) (b) from mice exposed to normoxic hypercapnia for 7 days. NC, normocapnia; HC, hypercapnia. (c,d) Validation in mouse lung and skeletal muscle cells. Fzd9 and Wnt7a expressions in MLE-12 cells (Ctrl, n = 22–23; 20%CO2, n = 5 per group), ASM cells (Ctrl, n = 22–23; 20%CO2, n = 5 per group) (c), or C2C12 myoblast (Ctrl, n = 18–19; 20%CO2, n = 4–5 per group) or myotube (Ctrl, n = 14–15; 20%CO2, n = 3–4 per group) (d) exposed to high CO2 for up to 24 hours (c) or 6 hours (d). Ctrl, control conditions. All values are represented as mean with error bars shown as the 95% confidence interval. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test.

Figure 3.

Validation of the transcriptomic datasets of hypercapnia in a human bronchial cell line and invertebrates. (a) FZD9 and WNT7a expression in BEAS-2B cells exposed to high CO2 for up to 12 hours (Ctrl, n = 20–23; 20%CO2, n = 5–6 per group). Ctrl, control conditions. (b) Fz and wg expression in Drosophila S2 cells exposed to high CO2 for up to 30 min (Ctrl, n = 14–15; 20%CO2, n = 4–5 per group). All values are represented as mean with error bars shown as the 95% confidence interval. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test.

Discussion

Elevation of CO2 has been proposed to affect organismal pathobiology. In recent years, there is accumulating evidence on significant deleterious effects of elevated CO2 per se on cell, tissue and organismal functions7,9,11–18,21,22. However, little is known about the variation in the global transcriptional response to CO2 elevation among different cell types, tissues or species. Here, we provide a new systems-level understanding of high CO2-conserved effects across nematodes, flies, mice and humans regulating Wnt signaling pathway genes, which appears to be central to high CO2 gaso-signal.

Our data suggest that hypercapnia leads to changes in the expression of genes involved in a variety of biological processes in mouse tissues. Interestingly, the gene network diagram constructed from the hypercapnia-responsive genes among the tissues revealed a functionally similar group of genes that activate Wnt signaling pathway, which was not previously known to be regulated by high CO2. The Wnt pathway is a highly conserved signal transduction cascade in animals that has a critical role in many biological processes23–26. Wnt signals are also known to activate more than one type of signaling cascade or cross-talk with other signaling pathways, and result in integrated, context-dependent cellular responses23. We also observed hypercapnia-responsive Wnt pathway genes that were categorized into other signaling pathways (Table S2). The Wnt signaling pathway may cross-talk with various biological networks as an upstream regulatory signal in response to hypercapnia, which could help explain the significant effects of high CO2 on different cells and organisms3,7,9–18.

Alterations in expression of Wnt pathway genes may be of central importance in the systems-level understanding of organismal effects and pathobiology of hypercapnia. Despite different exposure conditions of hypercapnia in each microarray dataset, we observed multiple gene components of the Wnt pathway including Inositol trisphosphate receptor gated Ca2+ channel and cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) binding protein across species (Fig. S1). Furthermore, we found the hypercapnia-responsive transcription factors such as c-Myc, Oct-4 and c-Jun which are the target genes of the Wnt signaling across mouse tissues exposed to hypercapnia. In vitro experiments with the same levels of exposure suggest transient increases in expressions of Frizzled and Wnt ligand genes in cultured cells from different origins including epithelial, smooth muscle, skeletal muscle and macrophage-like lineage in mice, humans and Drosophila. Although the magnitude of hypercapnia and gene expression profile of the Wnt signaling pathway differ between each dataset, the biological interpretation of our data point to significant activation of Wnt pathway genes, suggesting an evolutionary role of elevated CO2 on Wnt signaling. Wnt signals can activate at least two distinct intracellular signaling, canonical or non-canonical pathways23. The canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway is characterized by cytosolic and nuclear β-catenin accumulation and the activation of certain β-catenin-responsive target genes. The non-canonical β-catenin-independent pathways include the calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII)-mediated Wnt/Ca2+ pathway and the small GTPase RhoA- and Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-dependent planar cell polarity pathway. Specifically, Wnt7a rapidly induces the local activation of CaMKII26 and directly interacts with Fzd9 to inhibit cell growth via activation of the JNK pathway27. Overexpression of Wnt7a increases expression of the Wnt-target transcription factor genes including c-Myc28,29 and c-Jun28. c-Myc can bind to the Fzd9 gene promotor and promotes Fzd9 expression30. Hypercapnia may activate the Wnt7a/Fzd9 signal, setting up a feedback loop via Wnt-target transcription factors that could enhance the Wnt pathway genes. It has also been suggested that Wnt signals activate a metabolic sensor AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in myotubes24 and muscle-specific RING finger protein-1 (MuRF-1) leading to muscle atrophy31. Interestingly, we have reported that CaMKII, RhoA, JNK, AMPK and MuRF1 are responsive to hypercapnia in physiological contexts. In mammals, hypercapnia impairs cell proliferation14 and alveolar fluid reabsorption via a Ca2+/JNK pathway4,9,17, leads to airway constriction via Ca2+/RhoA axis signaling7, AMPK/MuRF-1-dependent muscle atrophy11, and adipogenesis via CREB activation13. Hypercapnia is also known to induce Na,K-ATPase endocytosis in Drosophila melanogaster17 and lower fertility in Caenorhabditis elegans17 via activation of the JNK pathway. Together with these reports, our data suggest a linkage of Wnt signaling to the pathobiological changes induced by hypercapnia4,7,9,11,17.

Why elevated CO2 levels activate Wnt signaling in different tissues/cells and species is not completely understood. Wnt signaling pathway is one of the major pathways regulating tissue architecture during development and in homeostasis of adult tissues32. In the mammalian lung system, Wnt signal maintains stemness of alveolar type 2 cells and can trigger transdifferentiation into alveolar type 1 cells which are part of the gas exchange surface of the lung alveolus33. We reason that Wnt response during CO2 elevation (which occurs in human lung diseases) may represent an adaptive homeostatic mechanism against stress to preserve organismal function during noxious alterations in gaseous (CO2) levels. However, such a mechanism may well become maladaptive to cells, organs and organisms as observed in during prolonged hypercapnia7–18.

In summary, our transcriptomic analysis of multiple datasets revealed a previously unknown role of hypercapnia in the regulation of gene expression. We found a conserved genomic response to hypercapnia regulating Wnt pathway genes in lung and skeletal tissues and cells in mice, bronchial epithelial cells in humans as well as in flies and nematodes.

Methods

Reagents

All cell culture reagents were purchased from Corning Life Sciences. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Reagents for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) were purchased from Life Technologies. The mRNA Isolation Kit was purchased from QIAGEN.

Animals

Adult (9–11 weeks old) C57BL/6J male mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). All animals were provided with food and water ad libitum, maintained on a 14-hour light/10-hour dark cycle, and handled according to National Institutes of Health guidelines. All of the procedures involving animals were approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IS00000245 and IS00010662). For high CO2 exposure, animals were maintained in a Biospherix C-Shuttle Glove Box (BioSpherix) for 3 or 7 days. The chamber’s atmosphere was continuously monitored and adjusted with ProOx/ProCO2 controllers (BioSpherix) in order to maintain 10% CO2 and 21% O2, with a temperature of 20 °C–26 °C and a relative humidity between 30% and 50%. These settings resulted in arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) of ~80 mmHg and PaO2 of ~100 mmHg, whereas in animals maintained in room air PaCO2 was ~40 mmHg and PaO2 was ~100 mmHg10,11. The values of high PaCO2 are representative of CO2 levels encountered in patients with COPD and mechanically ventilated patients with the “permissive hypercapnia” modality7,22. The pH, PaCO2, and PaO2 values obtained after exposure to 10% CO2 for 3 or 7 days were very similar to the values achieved during renal compensation and distinct from acute respiratory acidosis10,11. None of the animals developed appreciable distress. At selected time points, animals were euthanized with Euthasol (pentobarbital sodium–phenytoin sodium) and trachea, whole lung, diaphragm and soleus were harvested. Then the tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA extraction.

Mouse multi-tissue microarray

Total RNA from skeletal muscle tissues was isolated with the miRNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Messenger RNA profiling was performed with an Agilent SurePrint G3 8 × 15 K mouse microarray containing 39,430 messenger RNAs (Sanger miRbase release 9.1), in accordance with the protocol described by the manufacturer (Agilent) and as previously described34. Results were compared by unpaired t test, and gene expression was considered to be significantly different between groups when p < 0.05. For lung transcriptomic analysis, we used the transcriptomic datasets previously described by us7. The lists of DEGs in each dataset were obtained by ≥1.4 fold-change with an adjusted p value ≤ 0.05. The identified DEGs were analyzed in the PANTHER classification system (http://www.pantherdb.org/) to determine enriched biological processes and categorize into signaling pathways. Gene signatures representing lung, diaphragm or soleus transcriptome changes in hypercapnia were further subjected to functional gene network analysis. Functional Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (FGSEA) was used to generate functional gene networks by metagrouping of individual gene term sets (referencing GO Biological Process and KEGG Pathways), based on function similarity. The GeneTerm Linker algorithm implemented in the “FGNet” package (R) was used to perform the analysis, which utilized nonredundant reciprocal linkage of genes and biological terms35. This methodology filters enrichment output results through reciprocal linkage between genes and terms to produce functional metagroups of key biological significance. Parameters set for this analysis included adjusted p-value < 0.05, minimum gene term support of 3. Genes were deemed “functional hub” genes if they belonged to more than one functional metagroup, suggesting a central role in regulation of biological processes. Networks generated utilizing this analysis were exported in GLM format for further analysis and visualization, using the “iGraph” package (R). Cytoscape 3.2.1 was used for analysis of edge weight, node connectivity, and betweenness within the networks. Transcription factors were not directly measured in our data but inferred from gene expression signatures based on unbiased predictive analysis of known upstream regulators of differentially expressed genes. This analysis was performed in GeneGO Metacore (Thomson Reuters). Venn diagrams were used to determine conserved representation of inferred transcription factors across different tissues and timed responses in hypercapnia.

Secondary analysis of available transcriptomic datasets of hypercapnia

Data from three studies investigating the transcriptomic response to hypercapnia in human bronchial epithelial cells (GSE110362), Caenorhabditis elegans18 and Drosophila melanogaster (GSE17444) were obtained. Differential expression analysis of each processed dataset was performed with ≥1.4 fold-change with an adjusted p value ≤ 0.05 in the PANTHER pathways classification system.

Cells lines and culture

MLE-12 cells (CRL-2110; ATCC) were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 µg/ml; culture medium).

Mouse ASM cell isolation and culture were performed as described elsewhere7. Briefly, the trachea from C57BL/6J mice was removed and transferred into culture medium. Connective tissue and airway epithelium were removed by firmly scraping the luminal surface. The trachea strips were cut into small pieces (~1 mm3) and cultured in culture medium at 37 °C in 5% CO2. ASM cells begin to migrate out of the fragments after 7 to 10 days. The cells were dissociated with 0.05% trypsin and subcultured in culture medium. Identification of mouse ASM cells was based on the morphology and expression of α-SMA. Mouse ASM cells of passage <6 were used in all the experiments.

C2C12 mouse myoblasts (ATCC, CRL1772) were cultured and differentiated as described elsewhere11. In brief, cells were allowed to grow in plates until they reached ∼90–95% confluence, and then culture media was changed to DMEM supplemented with 2% horse serum (differentiation media) for C2C12 myotube experiments. The differentiation media was renewed every 18–24 h, and cells were allowed to differentiate for 3 days.

Immortalized human bronchial epithelial cell line BEAS-2B were obtained from ATCC (CRL-9609) and grown in culture medium.

Drosophila S2 cells were obtained from the Dr. Silverman’s laboratory (University of Massachusetts Medical School).

CO2 medium and CO2 exposure for mammalian cells

For the different experimental conditions, initial solutions were prepared with DMEM/Ham’s F-12 medium/Tris base/MOPS base (3:1:0.25:0.25) containing 10% FBS or 2% horse serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin, as described elsewhere7,11. The buffering capacity of the medium was modified by changing its initial pH with Tris and MOPS base to obtain a pH of 7.4 at the various CO2 levels (pCO2 of 40 or ~120 mm Hg). In our prior work, the maximal effects of hypercapnia on signal transduction pathways was achieved at ~120 mmHg of CO2 with short (minute to hour) exposure conditions in lung cells7,9,17 and skeletal muscle cells11, the subsequent cellular experiments with high CO2 were performed under these conditions. Lower CO2 levels also activate the signaling pathways and have pathophysiologic effects but with more prolonged exposures. The desired CO2 and pH levels were achieved by equilibrating the medium overnight in a humidified chamber (C-Chamber, BioSpherix, Lacona, NY). The atmosphere of the C-Chamber was controlled with a PRO CO2 carbon dioxide controller (BioSpherix). In this chamber, cells were exposed to the desired pCO2 while maintaining 21% O2 balanced with N2. Before CO2 exposure, pH, pCO2, and pO2 levels in the medium were measured using a Stat Profile pHOx blood gas analyzer (Nova Biomedical, Waltham, MA). Experiments began by replacing the culture medium with the CO2-equilibrated medium and incubating in the C-Chamber for the desired time.

Maintenance of Drosophila S2 cells and CO2 exposure

Drosophila S2 cells were grown at room temperature and protected from light in Schneider’s insect medium containing 10% FBS (Valley Biomedical) and 0.2% Penicillin-Streptomycin (GIBCO). For cell attachment, plates were treated with 1 N HCl for 1 hour, washed 3 times with sterile water, 0.5 mg/mL Concanavalin A (Sigma) for 1 hour, washed once with sterile water. S2 cells were plated at a density of 2.0 × 106 cell per well in six-well plates with the medium and allowed to attach for 1 hour. For high CO2 treatments, initial solutions were prepared with Schneider’s insect medium/Tris base/MOPS base (4:0.25:0.25) containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. The buffering capacity of the medium was modified by changing its initial pH with Tris and MOPS base to obtain a pH of 7.2 at the CO2 level of ~120 mm Hg. The desired CO2 and pH levels were achieved by equilibrating the medium overnight in a C-Chamber protected from light and at room temperature. The atmosphere of the C-Chamber was controlled with a PRO CO2 carbon dioxide controller. Before CO2 exposure, pH, pCO2, and pO2 levels in the medium were measured using a Stat Profile pHOx blood gas analyzer. Experiments were started by replacing the culture medium with the CO2-equilibrated medium and incubating at room temperature and protected from light for the desired time.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR

To isolate total RNA from tissues and cells were homogenized directly in 700 µL of lysis/binding buffer provided by the miRNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). Complementary DNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using a qScript cDNA Synthesis kit (Quanta Biosciences, Beverly, MA) and mRNA expression level was determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using SYBR Green chemistry (Bio-Rad). Relative expression of the transcripts was determined according to the ∆∆Ct method using Rpl19 for mouse, RPL19 for BEAS-2B or RpL32 for Drosophila S2 cells as reference for normalization.

Statistical analysis

Statistical methods are described in the figure legends and in the relevant methods descriptions. Sample size (n) values used for statistical analyses are provided in the relevant figures. Exclusion criteria were pre-established. Individual samples may have been excluded on the basis of sample processing error during experimental work-flow. Statistical outliers were detected and removed based on Grubbs’ test criteria when appropriate. For qRT-PCR data analysis, normally distributed data were analyzed by parametric tests including an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test for two-group comparisons or a one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons with Dunnett’s post-hoc corrections for three or more groups. Variances were examined by F test or the Brown-Forsythe test. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 7.02, GraphPad Software). p values of < 0.05 were considered to be significant. All values are represented as means with error bars shown as the 95% confidence interval.

Supplementary information

Table S1: List of DEG commonly observed in more than two tissues in mice exposed to normoxic hypercapnia for 3 or 7 days.

Table S2: List of hypercapnia-responsive Wnt pathway genes in mice tissues, a human bronchial cell line, Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster.

Dataset S1: Processed data from mRNA microarray analysis of skeletal muscles isolated from C57BL/6J mice exposed to normoxic hypercapnia for 3 or 7 days.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Diego A. Celli (Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care, Department of Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University) and K.V. Pandit (Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine) for their technical assistance. This work was supported in part by the US National Institutes of Health (HL-071643, HL-147070, HL-107629 and HL-131745). M.S. was a David W. Cugell fellow. E.P.C. is funded by Science Foundation Ireland (15/CDA/3490).

Author contributions

M.S., E.L. and J.I.S. contributed to all study design and data interpretation and wrote the manuscript. M.A. and N.K. performed microarray experiments, and M.S., M.A., M.B.E. and S.B. analyzed the data. M.S. and L.C.W. executed animal experiments and analyzed the data. L.A.D., L.C.W., S.M.C.M., P.H.S.S., I.V., I.T.H., G.A.N., Y.G., K. S., E.P.C., C. T., A.B., C.J.G., G.J.B., G.R.S.B. and S.B. interpreted the data and wrote the paper. J.I.S., P.H.S.S. and G.R.S.B. provided funding and resources.

Data availability

The microarray data of mouse skeletal muscle tissues generated in this project can be found in Supplement (Data S1).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-54683-0.

References

- 1.Weir EK, Lopez-Barneo J, Buckler KJ, Archer SL. Acute oxygen-sensing mechanisms. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:2042–2055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haldar SM, Stamler JS. S-nitrosylation: integrator of cardiovascular performance and oxygen delivery. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:101–110. doi: 10.1172/JCI62854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cummins EP, Selfridge AC, Sporn PH, Sznajder JI, Taylor CT. Carbon dioxide-sensing in organisms and its implications for human disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014;71:831–845. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1470-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shigemura M, Lecuona E, Sznajder JI. Effects of hypercapnia on the lung. J. Physiol. 2017;595:2431–2437. doi: 10.1113/JP273781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laffey JG, Kavanagh BP. Carbon dioxide and the critically ill–too little of a good thing? Lancet. 1999;354:1283–1286. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02388-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.listed Na. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;342:1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shigemura Masahiko, Lecuona Emilia, Angulo Martín, Homma Tetsuya, Rodríguez Diego A., Gonzalez-Gonzalez Francisco J., Welch Lynn C., Amarelle Luciano, Kim Seok-Jo, Kaminski Naftali, Budinger G. R. Scott, Solway Julian, Sznajder Jacob I. Hypercapnia increases airway smooth muscle contractility via caspase-7–mediated miR-133a–RhoA signaling. Science Translational Medicine. 2018;10(457):eaat1662. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bharat A, et al. Pleural Hypercarbia After Lung Surgery Is Associated With Persistent Alveolopleural Fistulae. Chest. 2016;149:220–227. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vadasz I, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase regulates CO2-induced alveolar epithelial dysfunction in rats and human cells by promoting Na,K-ATPase endocytosis. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:752–762. doi: 10.1172/JCI29723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gates KL, et al. Hypercapnia impairs lung neutrophil function and increases mortality in murine pseudomonas pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013;49:821–828. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0487OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaitovich A, et al. High CO2 levels cause skeletal muscle atrophy via AMP-activated kinase (AMPK), FoxO3a protein, and muscle-specific Ring finger protein 1 (MuRF1) J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:9183–9194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.625715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casalino-Matsuda SM, et al. Hypercapnia Alters Expression of Immune Response, Nucleosome Assembly and Lipid Metabolism Genes in Differentiated Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:13508. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32008-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kikuchi R, et al. Hypercapnia Accelerates Adipogenesis: A Novel Role of High CO2 in Exacerbating Obesity. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2017;57:570–580. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0278OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vohwinkel CU, et al. Elevated CO(2) levels cause mitochondrial dysfunction and impair cell proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:37067–37076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.290056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nilsson GE, et al. Near-future carbon dioxide levels alter fish behaviour by interfering with neurotransmitter function. Nature Climate Change. 2012;2:201–204. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helenius IT, et al. Elevated CO2 suppresses specific Drosophila innate immune responses and resistance to bacterial infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:18710–18715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905925106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vadasz I, et al. Evolutionary conserved role of c-Jun-N-terminal kinase in CO2-induced epithelial dysfunction. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharabi K, et al. Elevated CO2 levels affect development, motility, and fertility and extend life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:4024–4029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900309106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor CT, Cummins EP. Regulation of gene expression by carbon dioxide. J. Physiol. 2011;589:797–803. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.201467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barreiro E, Sznajder JI, Nader GA, Budinger GR. Muscle dysfunction in patients with lung diseases: a growing epidemic. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015;191:616–619. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201412-2189OE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, et al. Insights into the Molecular Mechanisms of CO2-Mediated Regulation of Stomatal Movements. Curr. Biol. 2018;28:R1356–R1363. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nin N, et al. Severe hypercapnia and outcome of mechanically ventilated patients with moderate or severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:200–208. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4611-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sethi JK, Vidal-Puig A. Wnt signalling and the control of cellular metabolism. Biochem. J. 2010;427:1–17. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abiola M, et al. Activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling increases insulin sensitivity through a reciprocal regulation of Wnt10b and SREBP-1c in skeletal muscle cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai HL, et al. Wnts enhance neurotrophin-induced neuronal differentiation in adult bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells via canonical and noncanonical signaling pathways. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ciani L, et al. Wnt7a signaling promotes dendritic spine growth and synaptic strength through Ca(2)(+)/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:10732–10737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018132108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winn RA, et al. Restoration of Wnt-7a expression reverses non-small cell lung cancer cellular transformation through frizzled-9-mediated growth inhibition and promotion of cell differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:19625–19634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409392200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao L, et al. An integrated analysis identifies STAT4 as a key regulator of ovarian cancer metastasis. Oncogene. 2017;36:3384–3396. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong L, et al. A Conditioned Medium of Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Overexpressing Wnt7a Promotes Wound Repair and Regeneration of Hair Follicles in Mice. Stem Cells Int. 2017;2017:3738071. doi: 10.1155/2017/3738071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawlor ER, et al. Reversible kinetic analysis of Myc targets in vivo provides novel insights into Myc-mediated tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4591–4601. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajasekaran MR, et al. Age-related external anal sphincter muscle dysfunction and fibrosis: possible role of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathways. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2017;313:G581–G588. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00209.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nabhan AN, Brownfield DG, Harbury PB, Krasnow MA, Desai TJ. Single-cell Wnt signaling niches maintain stemness of alveolar type 2 cells. Science. 2018;359:1118–1123. doi: 10.1126/science.aam6603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Konishi K, et al. Gene expression profiles of acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009;180:167–175. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1596OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fontanillo C, Nogales-Cadenas R, Pascual-Montano A, De las Rivas J. Functional analysis beyond enrichment: non-redundant reciprocal linkage of genes and biological terms. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: List of DEG commonly observed in more than two tissues in mice exposed to normoxic hypercapnia for 3 or 7 days.

Table S2: List of hypercapnia-responsive Wnt pathway genes in mice tissues, a human bronchial cell line, Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster.

Dataset S1: Processed data from mRNA microarray analysis of skeletal muscles isolated from C57BL/6J mice exposed to normoxic hypercapnia for 3 or 7 days.

Data Availability Statement

The microarray data of mouse skeletal muscle tissues generated in this project can be found in Supplement (Data S1).