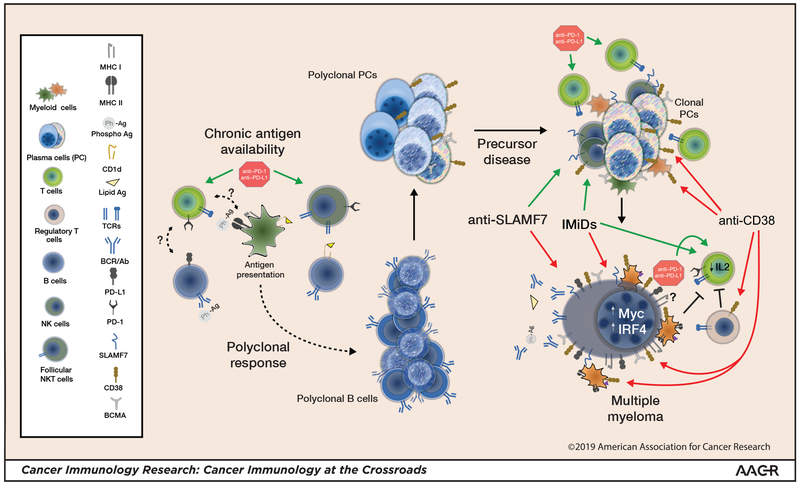

Figure 1: Myelomagenesis, myeloma, and modifying the immune response.

Lipid antigen or phosphoantigen (Ph-Ag)–reactive B cells give rise to phosphoantigen- and/or lipid antigen–reactive plasma cells. Follicular NKT cells, which are typically PD-1high , and possibly other helper T cells play a role. Ongoing chronic stimulation increases the potential for an emerging clonal myeloma precursor. T cell- and NK cell–mediated immune surveillance may limit myeloma progression. Frank progression to myeloma is associated with diminished T-cell and NK cell function and expansion of Tregs and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). IMiDs and mAbs lead to malignant plasma cell killing, which releases antigen and concurrently diminishes myeloma-driven suppressive mechanisms. Antigen release in the proper inflammatory milieu may elicit or expand an effector immune response. Anti–PD-1 could have pleiotropic effects, affecting both the effector response and follicular helper cell–mediated B-cell maturation. Combination strategies to shift the immune response toward an effector response could yield greatest clinical benefit. Green arrows: activation; Red arrows: inhibition; Blunted black lines: inhibition; (?): unknown effect.