Abstract

Objectives. To describe and control an outbreak of HIV infection among people who inject drugs (PWID).

Methods. The investigation included people diagnosed with HIV infection during 2015 to 2018 linked to 2 cities in northeastern Massachusetts epidemiologically or through molecular analysis. Field activities included qualitative interviews regarding service availability and HIV risk behaviors.

Results. We identified 129 people meeting the case definition; 116 (90%) reported injection drug use. Molecular surveillance added 36 cases to the outbreak not otherwise linked. The 2 largest molecular groups contained 56 and 23 cases. Most interviewed PWID were homeless. Control measures, including enhanced field epidemiology, syringe services programming, and community outreach, resulted in a significant decline in new HIV diagnoses.

Conclusions. We illustrate difficulties with identification and characterization of an outbreak of HIV infection among a population of PWID and the value of an intensive response.

Public Health Implications. Responding to and preventing outbreaks requires ongoing surveillance, with timely detection of increases in HIV diagnoses, community partnerships, and coordinated services, all critical to achieving the goal of the national Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative.

An estimated 92% of new HIV infections in the United States are transmitted by people who are either undiagnosed or diagnosed but not engaged in care.1 Because timely initiation of antiretroviral therapy enables rapid viral suppression among people with diagnosed HIV, identifying and intervening within transmission networks can effectively prevent HIV spread and reduce incidence. To achieve the ambitious goal of ending the HIV epidemic in the United States,1 prompt detection and response to clusters of recent and rapid transmission of HIV is increasingly important2 and requires integration of surveillance and prevention services and use of both traditional and novel approaches to ensure people living with HIV are diagnosed and linked to care. Molecular epidemiology has been described as transformative in public health as it allows identification of pockets of ongoing transmission of HIV that contact tracing alone may be unable to detect.2

We describe an outbreak of HIV that occurred among people who inject drugs (PWID) in northeastern Massachusetts. The successful identification and response to this outbreak involved stakeholders from across the HIV surveillance, prevention, and treatment community in Massachusetts and included one of the first uses of HIV molecular epidemiology to describe an outbreak and guide the control efforts (K. Buchacz, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], e-mail communication, June 11, 2019).

In August 2016, clinicians at a federally qualified health center in Lawrence, Massachusetts, notified the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH) of 5 HIV diagnoses among PWID. On average, less than 1 case of HIV infection per month among PWID had been reported in Lawrence during 2014 to 2015 from all health care providers. Subsequent investigation resulted in a focus on the cities of Lawrence and Lowell, former textile mill towns in the Merrimack Valley of northeastern Massachusetts, with populations of approximately 80 000 and 111 000, respectively.3 These cities have lower median incomes, higher poverty rates,3 and higher rates of both fatal and nonfatal opioid-involved overdoses4,5 than the Massachusetts statewide average.

Increases in opioid use, opioid-involved overdoses, and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections in Massachusetts had raised concern for potential introduction and transmission of HIV through unsafe injection drug use (IDU) practices.6 During 2011 to 2015 in Massachusetts, prevalence of opioid use disorder increased by approximately 50%, and the fatal opioid-involved overdose rate more than doubled7 to approximately twice the national average in 2014.8 During 2012 to 2013, the rate of fatal opioid-involved overdose per 100 000 population increased from 7.8 to 13.0 in Lawrence and from 8.3 to 23.3 in Lowell.5 Increasingly, opioid-involved overdose deaths in Massachusetts involve fentanyl, a potent synthetic opioid.7 Furthermore, the proportion of HCV cases identified among youths and young adults started to increase dramatically before 2011.6

Nevertheless, annual HIV diagnoses among PWID had decreased by 68% during 2006 to 2014.9,10 Recent outbreaks of HIV have occurred among PWID in Europe,11 and a 2015 HIV outbreak in Scott County, Indiana, also associated with the opioid crisis, occurred in a rural community in the United States.12 However, outbreaks had not previously been identified in urban areas of the United States where resources for HIV prevention and substance use disorder treatment are typically more accessible. A cluster of HIV infection among PWID in Seattle, Washington, identified in 2018, demonstrated the vulnerability of PWID, especially those experiencing homelessness, to HIV infection.13

In response to the regional increase in HIV diagnoses, MDPH conducted an outbreak investigation with support from the CDC that included case finding, laboratory testing, molecular analysis of HIV gene sequences, epidemiological analysis, and interviews with PWID and local stakeholders. Investigation goals were to describe the outbreak and determine why it happened in an urban Massachusetts location after a long period of increasing opioid use and HCV burden, but with limited previous evidence of significant HIV transmission, and to recommend control measures to reduce HIV transmission among PWID.

METHODS

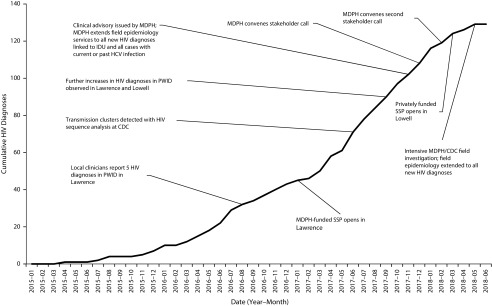

After the initial notification by clinicians in August 2016, MDPH used HIV and HCV surveillance data to examine all HIV diagnoses among PWID in northeastern Massachusetts. As a result of the initial investigation, MDPH initiated interventions, including enhanced outreach to PWID to encourage substance use treatment and to increase HIV testing. The Lawrence Board of Health authorized a syringe services program (SSP), which opened in January 2017. In May 2017, MDPH requested remote technical assistance from CDC. During fall 2017, further increases in HIV diagnoses among PWID were reported in both Lawrence and Lowell. In November 2017, MDPH issued a clinical advisory requesting that health care providers increase vigilance for HIV among PWID.14 MDPH held stakeholder calls in December 2017 and February 2018. On April 30, 2018, MDPH and CDC initiated an enhanced field investigation (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Cumulative HIV Diagnoses and Timeline of Investigation and Response to Outbreak of HIV: Massachusetts, 2015–2018

Note. CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; IDU = injection drug use; MDPH = Massachusetts Department of Public Health; PWID = people who inject drugs; SSP = syringe services program.

Case Definition and Case Finding

We included cases of HIV infection diagnosed during January 1, 2015, to June 30, 2018, that could be linked epidemiologically or molecularly to the investigation. Epidemiologically linked cases were HIV infections in PWID who received medical care, had experienced homelessness, resided or injected drugs in Lawrence or Lowell, or were injection or sex partners of these individuals. Molecularly linked cases were HIV infections with a partial HIV-1 polymerase (pol) gene nucleotide sequence linked at a genetic distance threshold of less than or equal to 0.015 substitutions per site15 to a sequence from 1 or more cases with a connection to Lawrence or Lowell.

MDPH collects demographic, risk, and clinical information on all people who receive a diagnosis of HIV infection; test results from ongoing HIV care, such as CD4+ lymphocyte counts and HIV viral loads are also reported,16 allowing longitudinal analyses. MDPH field epidemiologists interview people who received a diagnosis of HIV infection to assist in linkage to care and to identify and notify partners who may benefit from testing or other services.17 Until November 2017, MDPH limited field follow-up to those with acute HIV infection and as requested by a health care provider.

Laboratory and Analytic Methods

HIV pol gene nucleotide sequences were generated at CDC after polymerase chain reaction amplification, as described elsewhere12 or at commercial laboratories through similar gene amplification for genotypic testing for drug-resistance mutations. CDC’s laboratory analyzed samples through November 2017 (30 samples), after which MDPH rapidly implemented statewide HIV molecular surveillance. Commercial laboratories reported HIV pol sequences to MDPH for Massachusetts residents who had a drug-resistance genotype test conducted as part of routine clinical care during January 2016 to September 2018. The presence of mutations was established through a standard algorithm (https://hivdb.stanford.edu/hivdb/by-sequences). We analyzed sequences with Secure HIV-TRACE18 to identify molecular clusters with a pairwise genetic distance threshold of less than or equal to 0.015 substitutions per site (1.5%) and less than or equal to 0.005 substitutions per site (0.5%).15

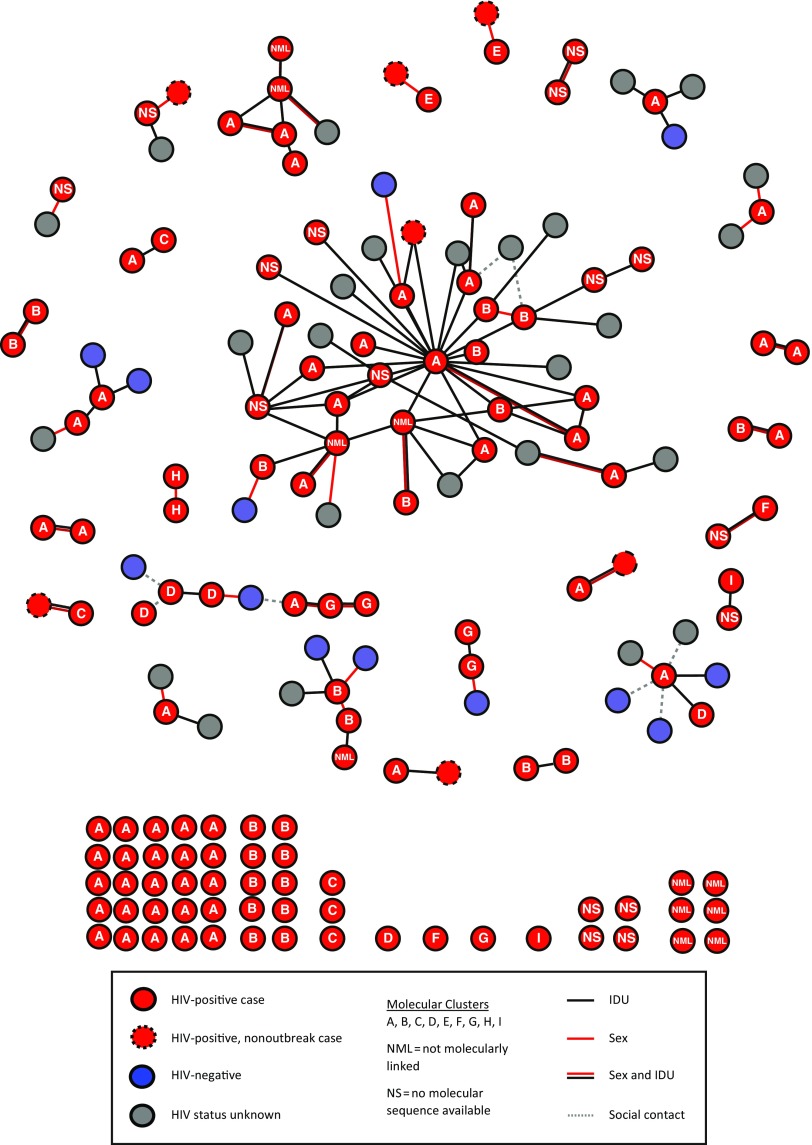

We determined the recency of HIV infection through antibody avidity testing by using the modified Bio-Rad HIV-1/HIV-2 Plus O EIA (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Redmond, WA) as described in detail elsewhere.18 We defined recent infection as an avidity index of less than or equal to 30%, indicating estimated infection within 221 days (95% confidence limits: 203.6, 238.7 days). We used MicrobeTrace (https://github.com/CDCgov/MicrobeTRACE/wiki) to construct diagrams of connections between cases and named contacts and of molecular links among cases to allow integration and visualization of both genetic and partner groups (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2—

Network Diagram of Needle Sharing or Sex Partner Interactions, as of September 30, 2018, Stratified by HIV Status and Molecular Cluster: Massachusetts, January 2015–June 2018

Assessment of Service Availability and Risk Behavior

To provide local context and to understand service availability, access, and HIV risk behaviors among PWID (including both drug use and sexual risk), we conducted semistructured interviews with stakeholders and both HIV-infected and non–HIV-infected PWID distinct from field epidemiology interviews. To be eligible for stakeholder interviews, participants needed to work with PWID in Lawrence or Lowell. Eligible PWID were aged 18 years or older, resided in Lowell or Lawrence, and reported IDU during the past 12 months.

We selected PWID for in-depth interviews by using a purposeful sampling technique to ensure variation based on sex, engagement in care, HIV status, and city of residence. Local stakeholders assisted investigators in identifying potential participants. Participants provided verbal consent and were reimbursed for their time.

RESULTS

As of June 30, 2018, the conclusion of the intensive field investigation, a total of 129 people met the case definition. Ninety-four (73%) had received a diagnosis of HIV infection when aged 20 to 39 years, 55 (43%) were female, and 87 (67%) were non-Hispanic White (Table 1). The most commonly reported exposure mode was IDU (n = 111; 86%), with smaller percentages reporting male-to-male sexual contact and IDU (n = 5; 4%), male-to-male sexual contact only (n = 1; 1%), heterosexual contact or presumed heterosexual contact (n = 7; 6%), and no risk identified (n = 5; 4%; Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). The initial CD4+ lymphocyte count was greater than or equal to 200 cells per cubic millimeter for 115 (89%) people, and the median earliest CD4+ count was 547 cells per cubic millimeter (Table A). Diagnoses peaked from April 2017 to January 2018 (Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Of 116 (90%) individuals positive for either HCV antibody (indicating past or current infection) or HCV RNA (indicating current infection), 99 received a positive HCV test result before receiving the HIV diagnosis. A positive HCV antibody or RNA-positive test result was first recorded by MDPH at a mean of 56 (median = 45) months before HIV diagnosis.

TABLE 1—

Demographic Characteristics of Individuals Linked to an HIV Outbreak During January 1, 2015, to June 30, 2018: Massachusetts

| Characteristics | No. (%) | Initially Molecularly Linked, No. (%) | Initially Epidemiologically Linked, No. (%) |

| Total | 129 | 36 (28) | 93 (72) |

| Age group at HIV diagnosis, y | |||

| 13–19 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| 20–29 | 50 (39) | 14 (39) | 36 (39) |

| 30–39 | 44 (34) | 8 (22) | 36 (39) |

| 40–49 | 23 (18) | 6 (17) | 17 (18) |

| ≥ 50 | 11 (9) | 8 (22) | 3 (3) |

| Sex at birth | |||

| Male | 74 (57) | 19 (53) | 55 (59) |

| Female | 55 (43) | 17 (47) | 38 (41) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 87 (67) | 25 (69) | 62 (67) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 4 (3) | 1 (3) | 3 (3) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 38 (29) | 10 (28) | 28 (30) |

| County of HIV diagnosis | |||

| Essex (includes Lawrence) | 45 (35) | 9 (25) | 36 (39) |

| Middlesex (includes Lowell) | 58 (45) | 14 (39) | 44 (47) |

| Other in Massachusetts | 24 (19) | 13 (36) | 11 (12) |

| Out of state | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 2015 | 7 (5) | 3 (8) | 4 (4) |

| 2016 | 36 (28) | 16 (44) | 20 (22) |

| 2017 | 65 (50) | 15 (42) | 50 (54) |

| 2018 | 21 (16) | 2 (6) | 19 (20) |

| Linkage to the investigation | |||

| Epidemiological only | 27 (21) | NA | 27 (29) |

| Molecular only | 29 (22) | 29 (81) | NA |

| Epidemiological and molecular | 73 (57) | 7 (19) | 66 (71) |

Note. NA = not applicable. Percentages may not add up to 100% because of rounding. No statistically significant differences in characteristics were identified for cases initially linked to the investigation through field epidemiologist interview compared with cases initially linked to the investigation through molecular surveillance. With Fisher exact test, all P values > .05.

During October 2017 to September 2018, viral load results were reported to MDPH for 113 (88%) cases, providing the most recent viral load test result taken within a year of analysis and allowing at least 3 months from latest possible time of diagnosis for viral suppression to be achieved. The most recently reported viral load during this period was less than 200 copies per milliliter (viral suppression) for 81 (63%) of 129, with a higher frequency of viral suppression among people who received a diagnosis during earlier years (Figure A).

Molecular Analysis and Recency Testing

Of 113 cases with available pol sequences, 102 (90%) were molecularly linked to 1 or more other cases at a genetic distance of less than or equal to 1.5%; of these, 93 linked to another case at a genetic distance of less than or equal to 0.5%. The linkages at a genetic distance of less than or equal to 1.5% formed 9 groups of 2 or more people, the 2 largest of which had 56 and 23 individuals, both including people from both Lawrence and Lowell. Of 129 cases, 36 (28%) without previously identified epidemiological links were initially linked by molecular analysis; by September 30, 2018, epidemiological links had been identified for 7 of these cases. As of September 30, 2018, 27 (21%) cases were only epidemiologically linked, 29 (22%) were only molecularly linked, and 73 (57%) were linked by both methods.

All cases in the 2 largest molecular clusters were HIV-1 subtype B. In the largest cluster, all pol sequences except 1 shared the nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase drug-resistance mutation K103N, which confers high-level resistance to nevirapine and efavirenz.

Of the 30 specimens tested for antibody avidity, 17 tested as recent (within 221 days) infections, and 13 were established infections. All people with results indicative of recent infection received HIV diagnoses within 3 months preceding specimen collection, and none were receiving antiretroviral treatment at the time of diagnosis.

Field Epidemiology

By September 30, 2018, field follow-up had been initiated for 120 (93%) people. Seventy-two interviewed individuals named 172 total contacts, representing 112 unique people. The 172 contact linkages formed 26 groups of 2 to 44 people. Seven groups included people from more than 1 molecular cluster (Figure 2). Needle sharing only accounted for 54% of partnerships; needle sharing and sex for 29%, and sex only for 17%. Ninety-eight (88%) named contacts had known connections to Lawrence or Lowell. Of 112 named contacts, 27 (24%) could not be contacted and were not tested for HIV infection, 13 (12%) tested HIV-negative, and 72 (64%) tested HIV-positive (Table B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Of these 72 people, 37 (51%) had received an HIV diagnosis before field epidemiology contact, 30 (42%) received HIV diagnoses because of field epidemiology contact, and 5 (7%) could not have a determination made based on available information.

In-Depth Interviews

Among 34 PWID interviewed, 20 reported injecting opioids, 4 stimulants, and 10 a combination of opioids and stimulants. Seven, all of whom used opioids, reported injecting more than 10 times per day. The increased frequency of injection associated with the introduction of fentanyl into the drug supply was prominent in interview responses. PWID were aware of the outbreak and of harm-reduction services in the area. PWID also reported frequent sharing of injection equipment and sharing of syringes when other options were unavailable. Sexual risk behavior for both women and men included exchanging sex for payment or drugs. All PWID interviewed had experienced homelessness within the past year.

We interviewed 19 stakeholders, including providers of substance use disorder services, HIV and emergency care, public health services, homelessness services, and law enforcement. Stakeholder interviews corroborated frequent injections associated with fentanyl use and common experiences of homelessness and incarceration among PWID. Prevention services in the region included an MDPH-funded SSP in Lawrence open 40 hours per week since January 2017, a privately funded SSP in Lowell open 4 hours per week since March 2018, and a privately funded mobile SSP that distributed injection equipment from a vehicle in both cities. SSPs distributed approximately 10 000 syringes in Lawrence in April 2018. Community health centers, hospital clinics, and private practices provided HIV testing, medication-assisted treatment, and HIV treatment in both cities; however, these services were not provided at emergency departments where PWID often presented for care19 or homeless shelters. The clinical advisory issued by MDPH in November 2017 had not reached all targeted stakeholders by their report.

Public Health Response

In November 2017, in response to the outbreak, MDPH extended field epidemiology follow-up to people with new HIV diagnoses attributed to IDU and HIV diagnoses among people with positive HCV RNA or antibody results reported in the state’s surveillance system. In May 2018, following a doubling of the team of field epidemiologists in Massachusetts, this was further extended to all new HIV diagnoses. Community involvement in response to the outbreak included consultative stakeholder meetings at the beginning and end of intensive field investigations that heightened stakeholder vigilance for HIV among PWID. SSP opening hours increased. An SSP in Lowell funded by MDPH following approval by the Lowell Board of Health was established in August 2018. HIV testing services were extended to emergency departments, homeless shelters, and jails. Total new HIV-related investment in the region by MDPH exceeded $1.7 million.

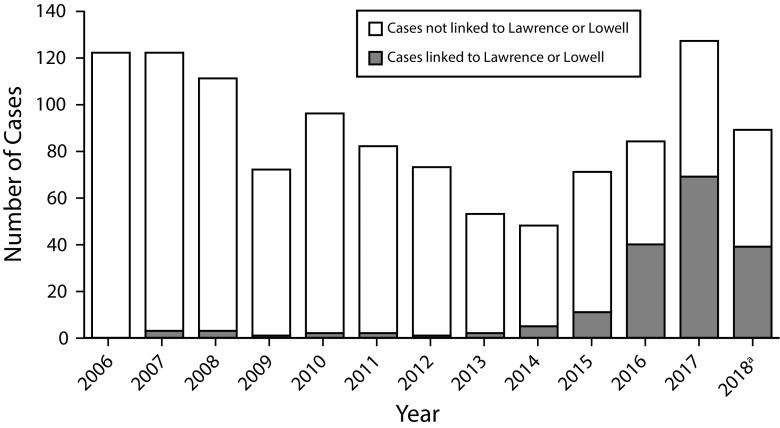

Following these interventions, MDPH surveillance recognized a substantial decrease in new IDU-related HIV diagnoses in the area. By June 4, 2019, the outbreak, including diagnoses since June 2018, had increased to 166 cases (35 only epidemiologically linked, 36 only molecularly linked, and 95 both epidemiologically and molecularly linked), including 7 outbreak-linked HIV diagnosis reports received in 2019, all between January and March). The outbreak-associated cases accounted for 52% of all HIV infection among PWID statewide in 2016 to 2017 and for all the increase in cases of HIV infection in PWID statewide (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3—

Diagnoses of HIV Among People Who Inject Drugs Statewide Showing Cases Linked to Lawrence and Lowell, Massachusetts: 2006–2018

a2018 data are preliminary.

DISCUSSION

This outbreak of HIV infection, primarily among PWID, occurred in an urban area with longstanding opioid-related problems.4,5 Unsafe injection practices were frequently reported. High-risk sexual behavior was also reported, and transmission of HIV occurred among people linked to the outbreak who did not report IDU. Molecular analysis supplemented field epidemiology, allowing characterization of the full extent of the outbreak and of networks of HIV transmission in circumstances in which interviews could not be conducted, and illustrated multiple introductions of HIV.

Beyond increasing the risk for overdose, fentanyl has been associated with more frequent injections because of its faster onset of effect and shorter duration of action.4 Participants in the qualitative interviews who used opioids reported frequent injection, sometimes more than 10 times per day. Having decreased from 2006 to 2014,10 annual new HIV diagnoses among PWID in Massachusetts increased beginning in 2015, shortly after fentanyl emerged in the drug supply.4,7 A large proportion of this increase related to the outbreak, and a number of cases reported in other parts of the state were linked to the outbreak (Figure 2).

Syringe distribution through SSPs was insufficient for the high frequency of injection associated with fentanyl use. Increasing access to sterile injection equipment in hard-to-reach populations requires novel approaches, including mobile SSPs and encouragement of secondary syringe exchange, and programs to address community concerns.20 SSP and medication-assisted treatment use decrease the risk for HCV infection21,22 and HIV23,24 transmission among PWID and help prevent outbreaks of HIV associated with IDU24 by reducing sharing of injection equipment and frequency of injection, respectively. Shortly after the intensive field investigation, the Lowell Board of Health authorized an SSP; SSP funding from MDPH followed. MDPH expanded HIV testing through mobile testing services at SSPs and homeless shelters, and engagement with hospital emergency departments and substance use disorder treatment centers. MDPH has hired additional field epidemiologists and expanded follow-up to all people with newly diagnosed HIV infection.

Laboratory testing indicates that HIV infection was being diagnosed early in the course of disease for many, but not all, patients in this investigation. The median earliest CD4+ lymphocyte count (547 cells/mm3) was higher in this outbreak than in Massachusetts overall during a similar time period (398 cells/mm3; K. Cranston, MDPH, oral communication, November 9, 2018). Of the 30 samples available for antibody avidity recency testing, 17 (57%) indicated recent infection. Furthermore, the high proportion of cases molecularly linked at a genetic distance of less than or equal to 0.5% indicated recent transmission.

Despite very high health insurance coverage in Massachusetts3 and all participants in qualitative interviews reporting having health insurance, challenges remain with engagement in and adherence to treatment and retention in care for people living with HIV. As of September 30, 2018, HIV viral suppression had been achieved in 63% of cases, and 12% had not had a viral load test within the previous year, compared with 79% viral suppression among all cases of HIV diagnosed across Massachusetts during 2015, as measured on January 1, 2018.25

Service providers cited homelessness and incarceration as common stressors for PWID. High levels of mobility and social instability may lead PWID to seek care in multiple locations, resulting in fragmentation of care or no care at all. Unpredictable release dates from incarceration and difficulty coordinating transition to care after release can produce interruptions in HIV care,26 which providers noted despite MDPH-funded linkage-to-care services associated with county jails.

Astute clinicians noticed the increase above baseline in HIV diagnoses among PWID and notified MDPH. The local knowledge of stakeholders was valuable in understanding the context in which the outbreak developed and in guiding investigation and control efforts including provision of care and other services. Community meetings held at the start and end of intensive field investigations facilitated collaboration and introduction of HIV testing in homeless shelters. Despite the issuance of a clinical advisory, some stakeholders were unaware of the increase in HIV diagnoses early in the course of the outbreak. This revealed opportunities for improvement in communication among MDPH, local health departments, and other stakeholders.

Limitations to this investigation and outbreak response include the limited field epidemiology resources that constrained contact tracing. Although the providers we spoke to stressed the wide penetration of fentanyl into the local opioid supply, we were not able to review toxicology results from case-patients, and field epidemiology interviews did not ask about types of drugs used where individuals reported IDU. Results of qualitative interviews cannot be generalized to outbreak cases or the population of PWID. The investigation and publicity about the outbreak could have increased awareness among PWID of the outbreak and local services. Although we explored temporal trends in volume of HIV testing and results of tests performed at the Massachusetts State Public Health Laboratory (data not shown), we lacked access to data from private laboratories and could not gauge the total volume of HIV testing over time. However, the number of positive HIV tests reported to MDPH from all clinical laboratories in the state and the proportion of positive tests performed at the Massachusetts State Public Health Laboratory remained consistent over the past decade, indicating that testing availability has been consistent. Furthermore, the median earliest CD4+ count was higher among those involved in this outbreak than among all cases of HIV diagnosed in the state, indicating that testing is accessed by PWID in Lawrence and Lowell.

To conclude, despite health insurance coverage and harm-reduction services, HIV emerged among PWID in the context of homelessness, incarceration, and other determinants of HIV risk.27 Because of more frequent injection, fentanyl may have increased the opportunity for HIV transmission. Similar environments exist in many other US cities, especially in Massachusetts and across New England where fentanyl is widespread.28,29

Longstanding community partnerships helped with detection and response to this outbreak and illustrate the importance of collaborations between public health and local stakeholders. Molecular surveillance helped characterize this outbreak, and its expanded use will aid future outbreak detection and characterization to enable prompt investigation and intervention. The decline in new outbreak-linked HIV diagnoses since the implementation of control measures demonstrates the value of a timely response to an increase in HIV diagnoses.

Prevention of future outbreaks will require the preemptive deployment of services, including SSPs, medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder,30 targeted HIV testing, and case management to minimize HIV transmission among PWID and maximize retention in care and viral suppression among people living with HIV. National efforts to eradicate HIV infection depend on this level of readiness and response, particularly in populations such as PWID with currently low rates of new HIV infection, but with the potential for viral reintroduction and rapid transmission.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Chris Bositis and Amy Bositis in Lawrence, Massachusetts, and Kerran Vigroux, Jaime Dillon, Judy Lethbridge, and The Community Opioid Outreach Program in Lowell, Massachusetts, for their work with people living with HIV and people who use drugs in northeast Massachusetts. We would also like to thank Wei Luo and Silvina Masciotra of the Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention at CDC for their work with recency testing of HIV samples related to this outbreak.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The investigation was approved by CDC as a nonresearch disease control activity in accordance with federal human participant protection regulations and CDC policies and procedures.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Fauci AS, Redfield R, Sigounas G, Weahkee M, Giroir B. Ending the HIV epidemic, a plan for the United States. JAMA. 2019;321(9):844–845. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oster AM, France AM, Mermin J. Molecular epidemiology and the transformation of HIV prevention. JAMA. 2018;319(16):1657–1658. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Census Bureau. American Community Survey Data Profiles 2012–2016 5 year estimate. Available at: https://www.census.gov/acs/www/data/data-tables-and-tools/data-profiles/2016. Accessed October 23, 2018.

- 4.Ciccarone D, Ondocsin J, Mars S. Heroin uncertainties: exploring users’ perceptions of fentanyl-adulterated and -substituted “heroin.”. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;46:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Data brief: opioid-related overdose deaths among Massachusetts residents, 2017. Available at: https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2018/02/14/data-brief-overdose-deaths-february-2018.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2018.

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C virus infection among adolescents and young adults—Massachusetts, 2002–2009. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(17):537–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massachusetts Department of Public Health. An assessment of fatal and nonfatal opioid overdoses in Massachusetts (2011–2015) August 2017. Available at: https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2017/08/31/legislative-report-chapter-55-aug-2017.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2018.

- 8.CDC WONDER. Multiple Cause of Death 1999–2016. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. 2015. Available at: https://wonder.cdc.gov. Accessed October 23, 2018.

- 9.Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Services. Massachusetts Integrated HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care Plan. September 1. 2018. Available at: https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2018/01/09/mass-hiv-aids-plan.docx. Accessed January 25, 2019.

- 10.Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Massachusetts HIV/AIDS epidemiological profile: people who inject drugs. 2017. Available at: https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2018/06/25/idu.docx. Accessed October 23, 2018.

- 11.Des Jarlais DC, Kerr T, Carrieri P, Feelemyer J, Arasteh K. HIV infection among persons who inject drugs: ending old epidemics and addressing new outbreaks. AIDS. 2016;30(6):815–826. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peters PJ, Pontones P, Hoover KW et al. HIV infection linked to injection use of oxymorphone in Indiana, 2014–2015. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(3):229–239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1515195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golden MR, Lechtenberg R, Glick SN et al. Outbreak of human immunodeficiency virus infection among heterosexual persons who are living homeless and inject drugs—Seattle, Washington, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(15):344–349. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6815a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massachusetts Department of Public Health Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Science. Clinical advisory: HIV transmission through injection drug use. November 27, 2017. Available at: https://www.mass.gov/lists/hiv-treatment-guidelines-and-clinical-advisories. Accessed October 23, 2018.

- 15.Oster AM, France AM, Panneer N et al. Identifying clusters of recent and rapid HIV transmission through analysis of molecular surveillance data. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;79(5):543–550. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Commonwealth of Massachusetts. 105 CMR 300.000: Reportable diseases, surveillance, and isolation, and quarantine requirements. Available at: https://www.mass.gov/regulations/105-CMR-30000-reportable-diseases-surveillance-and-isolation-and-quarantine. Accessed October 23, 2018.

- 17.Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Science. Guide to surveillance, reporting and control. 2018. Available at: https://www.mass.gov/handbook/guide-to-surveillance-reporting-and-control. Accessed October 23, 2018.

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Detecting and responding to HIV transmission clusters. A guide for health departments. June 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/funding/announcements/ps18-1802/CDC-HIV-PS18-1802-AttachmentE-Detecting-Investigating-and-Responding-to-HIV-Transmission-Clusters.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2019.

- 19.Nambiar D, Spelman T, Stoové M, Dietze P. Are people who inject drugs frequent users of emergency department services? A cohort study (2008–2013) Subst Use Misuse. 2018;53(3):457–465. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2017.1341921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benyo A. Promoting secondary exchange: opportunities to advance public health. Harm Reduction Coalition. 2006. Available at: https://harmreduction.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/promotingsecondaryexchange.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2018.

- 21.Platt L, Minozzi S, Reed J, Vickerman P et al. Needle syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy for preventing hepatitis C transmission in people who inject drugs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9:CD012021. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012021.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris MD, Shiboski S, Bruneau J et al. Geographic differences in temporal incidence trends of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs: the InC3 Collaboration. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(7):860–869. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janowicz DM. HIV transmission and injection drug use: lessons from the Indiana outbreak. Top Antivir Med. 2016;24(2):90–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strathdee SA, Beyrer C. Threading the needle—how to stop the HIV outbreak in rural Indiana. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(5):397–399. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1507252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Sciences. Massachusetts HIV/AIDS epidemiologic profile. The Massachusetts HIV Care Continuum. 2018. Available at: https://www.mass.gov/lists/hivaids-epidemiologic-profiles. Accessed June 27, 2019.

- 26.Hammett TM, Donahue S, LeRoy L, Montague BT. Transitions to care in the community for prison releasees with HIV: a qualitative study of facilitators and challenges in two states. J Urban Health. 2015;92(4):650–666. doi: 10.1007/s11524-015-9968-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health among adults with diagnosed HIV infection in 13 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, 2015. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. August 2017;22(3). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Accessed October 23, 2018.

- 28.Springer YP, Gladden RM, O’Donnell J, Seth P. Notes from the field: fentanyl drug submissions—United States, 2010–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(2):41–43. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6802a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drug Enforcement Administration National Forensic Laboratory Information System. NFLIS Brief: Fentanyl, 2001–2015. March 2017. Available at: https://www.nflis.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/DesktopModules/ReportDownloads/Reports/NFLISFentanylBrief2017.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2019.

- 30.Van Den Berg C, Smit C, Van Brussel G et al. Full participation in harm reduction programmes is associated with decreased risk for human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus: evidence from the Amsterdam Cohort Studies among drug users. Addiction. 2007;102(9):1454–1462. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01912.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]