Abstract

This systematic review examined the validity of generic coping-with-stress measures in the relationships between avoidance-type coping and psychosocial adaptation to chronic illness and disability. Major data bases were searched for studies on the association between avoidance-type coping and psychosocial adaptation to chronic illness and disability. Findings indicated that reliance upon avoidance-type coping is linked to reports of poorer psychosocial adaptation. The veracity of these findings must be treated cautiously owing to conceptual, structural, psychometric, and other issues. Users of generic coping measures should consider these concerns prior to empirically investigating the link between generic avoidance-type coping measures and psychosocial adaptation among people with chronic illness and disability.

Keywords: avoidant coping, chronic illness, chronic illness and disability, coping, denial, disability, measurement, psychosocial adaptation, scale

The role played by avoidant-type coping (ATC) strategies in influencing psychosocial adaptation to life stresses and traumas and, more specifically, to chronic illnesses and disabilities (CIDs) has been of interest to researchers and clinicians for over half a century (Kortte, Veiel, Batten & Wegener, 2009; Livneh and Martz, 2012; Penley et al., 2002; Suls and Fletcher, 1985). Although far from reaching a consensus among scholars, the term “avoidant coping” (or ATC) has alternatively been used to refer to coping responses, reactions, modalities, and strategies such as denial, wishful thinking, escape (social) withdrawal, distancing, distraction, minimization, and in general, any mode that indicated behavioral, emotional, and/or mental disengagement (Skinner et al., 2003; Zeidner and Endler, 1996). A more concise description was provided by Hagger and Orbell (2003), which states that avoidant coping addresses “cognitive or behavioral attempts to ignore or avoid the existence of the problem or illness” (p. 164).

The literature suggests that, when dealing with most stressful conditions, the use of ATC is largely ineffective in reducing physical and emotional distress, depression, and anxiety, when confronting stressful life events and health-related conditions (Adams et al., 2017; Iturralde et al., 2017; Kvillemo and Branstrom, 2014; Zeidner and Saklofske, 1996). Furthermore, the reliance on ATC strategies has also been typically linked to concurrent and future poorer indicators of psychosocial adaptation among individuals with a wide range of medical conditions including amputation, cancer, diabetes, heart disease, spinal cord injuries (SCI), multiple sclerosis (MS), traumatic brain injuries (TBI), rheumatoid arthritis, and pain, among others. Inconsistent with these findings, however, are sporadic reports of ATC, and in particular denial coping, being independent of psychosocial outcomes (e.g. Classen et al., 1996; Duangdao and Roesch, 2008; Pereira et al., 2018; Tomberg et al., 2005).

Since the early 1980s, with the advent of the first formal, theoretically derived, and quantitively scored coping measure (the Ways of Coping Checklist (WCC), Folkman and Lazarus, 1980), along with its more recent version (Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ), Folkman and Lazarus, 1988), efforts to measure coping have proliferated in the field of coping with stress and trauma to include, among others, scales such as: The Coping Responses Inventory (CRI; Billings and Moos, 1981; Moos, 1993), The Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced (COPE) Inventory (Carver et al., 1989) and its later abbreviated format (the Brief COPE; Carver, 1997), the Coping Strategies Inventory (CSI; Tobin et al., 1989), the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS), Endler and Parker, 1999), and the Coping Strategies Indicator (Amirkhan, 1990). Common to all these measures was the recognition of the importance of not merely addressing typically adaptive, positively valanced coping efforts (e.g. problem-solving, planning, seeking social support, and positive appraisal), but also the deployment of conceptually nonadaptive, negatively valanced coping modalities. Foremost among these latter coping efforts, normally depicted as (sub)scales are: (a) distancing, (b) escape, (c) problem avoidance, (d) wishful thinking, (e) social withdrawal, (f) self-distraction, (g) denial, (h) minimization, (i) behavioral disengagement (BD), and (j) mental disengagement (MD). These ATC scales, as well as all other existing coping scales, were developed (and, where pertinent, normed) in the context of generic life stressors that seldom addressed coping with the aftermath of the onset of severe or CIDs. A review of these scales indicates that respondents are being asked to report on coping efforts with stressful experiences that typically involve one’s family, friends, job, finances, school, natural disasters, and loss or death of a relative or a friend. Coping with CID is largely left unaddressed. Granted, several of the studies have requested that respondents consider how they have been coping with a particular medical condition, yet even in many of these studies no specific information is provided to respondents as to what they should specifically consider when contemplating their answers (e.g. pain, functional limitations, threat to life, treatment complications, and future implications; see also Manne, 2003). Furthermore, since in several of these instruments, respondents are requested to first define their own stressful event (e.g. chemotherapy effects, impaired mobility, and experienced pain), and since perceived stressors invariably differ across individuals in their severity level, duration, impact on various life domains, and personal significance or meaning, it is highly conceivable that their perceptions of coping, including ATC, would be differentially appraised and deployed. Finally, the psychometric soundness of these ATC scales has not been formally explored with CID populations, and due to the aforementioned concerns about their appropriateness for people with CID, may be compromised in the reported empirical literature.

In the absence of any firm confirmation that assessment of ATC by generic coping-with-stress scales presents a valid approach to investigating adaptation among people with severe and chronic medical conditions, the main purpose of this systematic review was to carefully examine the validity of such measures to explore the association between ATC and psychosocial adaptation to CID in these populations.

Method

To address the study’s aim, two separate methods were undertaken. First the conceptual, structural, and procedural features of the various coping scales were scrutinized by reviewing their manuals, their initial publications, and all available data from subsequently published materials. Second, the available quantitative data, yielded from the construction of these scales, as well as the reported psychometric features of these scales, including empirically reported studies seeking to establish their link to psychosocial outcomes among selected groups of people with CID, were also examined. The following section describes these methods.

Procedure

For the purposes of this review, 14 consecutive major database searches were conducted during a 3-year period (2015–2018). These included the following sources: PsychINFO, ERIC, MEDLINE, Social Work References Center, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. Reference lists of all studies eligible for inclusion in the review were also examined to identify any additional relevant articles. Terms (keywords) used in the search included the following: (a) Six ATC-related terms: “avoidant coping,” “denial,” “escape,” “disengagement coping,” “wishful thinking,” and “distraction”; (b) titles of the six primary coping measures examined in this study (WCC/WOC/WCQ, CRI, COPE, Brief COPE, CSI, and CISS); and (c) six types of CIDs: “cancer,” “spinal cord injury,” “heart/cardiac conditions,” “multiple sclerosis,” “amputation,” and “traumatic brain/head injury.”1 In each of the above combined searches, the presence of eight psychosocial adaptation outcome terms were then examined, namely, “depression,” “anxiety,” “distress,” “quality of life (QOL),” “well-being,” “life satisfaction,” “adaptation,” and “adjustment.” Searches in which these terms were not revealed were not further pursued. For example, a typical search was conducted in the following manner: Step 1: the domains of CID, ATC, and specific coping measures were crossed (e.g. “amputation,” and/or “avoidant,” and/or “WCQ”), yielding a certain list of plausible articles and Step 2: for each of the “hit” articles, from the previous search, Abstracts and, if needed, Methods/Measures sections were.

Inclusion criteria included the following: (a) published during the time period of 1983 (earliest available use of selected coping measures) to 2018 (date of final search), (b) published in the English language, (c) published in a peer-reviewed journal, (d) reported measurements of ATC and psychosocial outcomes in quantitative manner, (e) included samples of only adult (18+ years of age) respondents, (f) used only pre-selected, generic coping (with stress and trauma) measures/scales, (g) employed either cross-sectional or longitudinal research designs, and (h) were limited to “human subjects.” Exclusion criteria, therefore, encompassed studies which reported children- or young adolescent-based findings, qualitative or review papers, CID-specific only (e.g. heart disease, multiple sclerosis, and cancer) measures of coping (e.g. Levine et al., 1987; Pakenham, 2001; Watson et al., 1988), and coping which was assessed within the context of excluded disabling conditions.

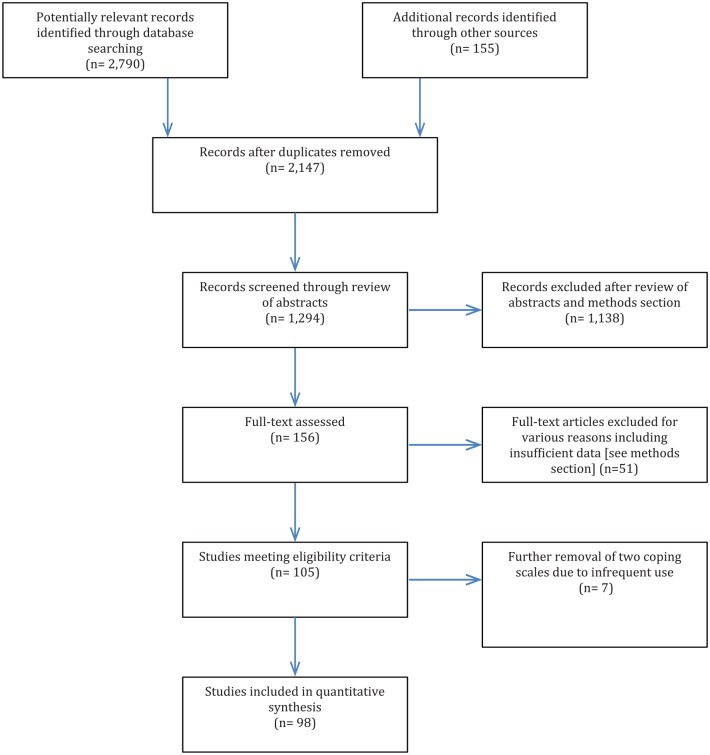

Using the above search terms 2945 studies reporting empirical findings on the association between measures of ATC and psychosocial adaptation outcomes to the above listed six types of CID were initially identified. A follow-up set of analyses (Figure 1) which removed duplicate articles, carefully reviewed abstracts (and when needed full texts), and limited inclusion to only adult populations, English language published refereed journals, and appropriately reported psychosocial adaptation outcomes (e.g. QOL, well-being, depression, and anxiety) within the earlier identified CIDs, cble studies to 156. These 156 articles, found to be eligible for inclusion, were subsequently carefully re-examined to determine their appropriateness for inclusion in the review. In total, 53 additional articles whose data and methods reflected unclear age groups, participant selection, cause of disabling condition, as well as ambiguous usage of ATC or psychosocial outcomes, resulted in a final sample of 103 articles. Finally, data derived from records of two of the coping scales (CSI and CISS) were also removed from further analysis due to infrequent use by researchers (n = 3 and n = 4, respectively), resulting in a final sample of 96 studies.2

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Data extracted from the eligible records included the following variables: date of publication, sample size, respondents’ age range and mean/median age, type of CID, type of coping measures employed (and its version), timing of assessment (in longitudinal research designs), time since injury/diagnosis (mean values/medians and ranges in weeks, months, or years), study research design, internal reliability (and if available test–retest stability) coefficients for the ATC measures/scales, type of employed outcome measures/indicators, correlation coefficients between predictor (ATC), and outcome (psychosocial adaptation) measures. Regarding the use of outcome measures, the widely heterogeneous range of measures was divided into four categories, namely, positively valanced (e.g. QOL, well-being, and life satisfaction), negatively valanced (distress, depression, and anxiety), mixed (both negative and positive outcomes included) and “other” (mostly trait-like constructs, such as hope, optimism, self-efficacy, acceptance, or performed activities such as community participation). Since the aim of this study was not meta-analytic in nature, and since no intervention-based effect sizes were sought, these indices were not obtained or calculated.

A thematic list of topics, issues, and concerns that emanated directly from each coping scale manual, the various published and abbreviated revisions of these scales, and the reviewed research (empirical) articles was carefully prepared. These pertained to the nature, structure, processes, and procedures employed by the researchers and in which ATC was associated with CID-linked psychosocial outcomes. More specifically, the list of topics was created using the following three sources: (a) data extracted from all available coping scales manuals (e.g. scale development, selection of items, and norming procedures, reported validity and reliability indices, item analysis); (b) previous comprehensive reviews of coping with the onset of CID (e.g. Chronister et al., 2009; Livneh and Martz, 2012); and (c) information typically provided in published work on coping with and psychosocial adaptation to CID (e.g. conceptualization of the relationship between coping and adaptation, research design, sample characteristics, psychometrics of employed scales, nature and meaning of findings, and reached conclusions). Accordingly, focus was placed upon the following: (a) the rationale underlying the use of the omnibus coping measure and, more specifically, the ATC (sub)scale; (b) available sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. age and gender) and medical features (e.g. duration of CID and severity level) of the recruited CID sample(s); (c) the psychometric data reported for the ATC scale(s); (d) the employed research design; (e) the veracity of the reported findings (i.e. the reported relationships between ATC and psychosocial outcomes); (f) the conclusions reached by the authors and their theoretical, clinical and research implications and applications; and (g) the limitations acknowledged by the researchers. No coding system was implemented in this review since all categories, and yielded quantitative data, were extracted based solely on previously established categories (e.g. age, gender, type and duration of CID), and required no subjective assessment by the researcher.

Measures

The rationale for including the pre-selected four generic coping measures stemmed from their high frequency use, established both from the extant literature (e.g. Kato, 2015), and following an earlier review by the author. It was found that almost 90% of the published research, on coping among people with CID, employed these measures. Two additional measures (i.e. the CSI and CISS) were used infrequently as measures of coping with CID, and were eliminated from further consideration, following an earlier search. Accordingly, this section reviews the selected measures with particular emphasis on their ATC (sub)scales.

The WCC/WCQ

The WCC and the WCQ (Folkman et al., 1986; Folkman and Lazarus, 1988) is a 66-item,3 8-scale instrument in which respondents are asked to specify a stressful situation that occurred during the past week. Respondents are then required to specify the extent to which they use each of the listed items when confronting that event. The measure includes two ATC scales, namely, distancing (6 items, α = .61; Folkman et al., 1986), and escape-avoidant (8 items, α = .72; Folkman et al., 1986). The first scale (distancing) describes attempts of cognitive detachment, refusal to think about the event, and engaging in positive, even if unrealistic, outlook. The second scale describes attempts of wishful thinking and BD from the stressful situation. A revised and shorter (42 items; five subscales) version of the scale (WCC-R) was introduced by Vitaliano et al. (1985) and has been widely used by stress and coping researchers.

The WCC/WCQ measures were derived from Lazarus and Folkman (1984) stress and coping theory which regards psychological coping with stress as a transactional endeavor, where the person and the environment within which he or she is anchored, are viewed dynamically, and where reciprocal relationships between the two are ongoing. Coping is viewed as a reflection of the individual’s cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage the demands of the person–environment transaction. Distancing and escape-avoidance exemplify efforts to regulate one’s emotions in the presence of stressful encounters.

The CRI

The CRI (Moos, 1993) underwent several modifications over the years. In its original form (Billings and Moos, 1981) it consisted of three primary scales, namely, active-cognitive strategies (11 items), active behavioral strategies (13 items), and avoidant-orients strategies (8 items) (Holahan and Moos, 1987). The most recent version (Moos, 1993), is comprised of two primary “meta-scales,” each further divided into four scales. The second “meta-scale” is termed Avoidance Coping Strategies and includes the following 6-item scales: (a) cognitive avoidance (α = .72), (b) acceptance/resignation (α = .64), (c) seeking alternative rewards (α = .68), and (d) emotional discharge (α = .62). Only the cognitive avoidance scale appears to reflect veridical avoidance-linked responses to stress. It focuses on mental efforts to avoid realistic thinking about the stressful or problematic situation. Respondents are required to first identify and describe the most important problem, or stressful situation, they have experienced in the last 12 months, and then to assess its impact, and then to rate each of the CRI 48 items, based on his or her behavior in connection with the problematic or stressful situation.

The CRI evolved from Moos and his colleagues (Holahan and Moos, 1987; Moos and Schaefer, 1986) integrative framework that adopts a multi-component conceptualization of coping with and adaptation to stressful situations. The model depicts a multi-panel recursive structure of human functioning, in which the central component is that of situation-specific coping strategies links the environment (e.g. existing external stresses) personal systems (e.g. personality traits), transitory conditions (e.g. life events), with outcomes (e.g. well-being indicators (Moos and Holahan, 2007)).4

The COPE Inventory and the Brief COPE

The COPE Inventory (Carver, 2013; Carver et al., 1989) and its abbreviated form the Brief COPE (Carver, 1997), were constructed by their authors partly based upon the earlier conceptualizations of Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) transactional model and its empirical applications (e.g. the WCQ), and partly based on their own behavioral self-regulation model (Carver and Scheier, 1982; Scheier and Carver, 1988). The 14-scale measure (a 15th scale was added later on), titled COPE, includes 4-item each, four scales which are purported to address ATC. The scales are denial (α = .71), BD (α = .63), MD (α = .45), and alcohol and drug disengagement (ADD; 1-item).5 The BD and MD scales were regarded by the authors as reflecting “dysfunctional” coping. The Brief COPE is comprised of 28 items (14 subscales each with 2 items) and includes four ATC subscales, namely, self-distraction, denial, behavioral disengagement, and substance use.

Results

Table 1 provides a descriptive view of the main empirical findings yielded by the literature search. The reported findings describe the: (a) types and durations of reviewed CIDs, (b) research designs used, (c) adherence to original form of the ATC scales, (d) employed psychosocial outcome measures, and (e) strength of association between ATC and psychosocial adaptation indices. The section concludes with empirical findings on the nature of the relationships between ATC and outcome measures of adaptation, and the psychometric soundness (e.g. reliability coefficients) of the adopted ATC scales.

Table 1.

Summary of the literature on the use of avoidant-type coping measures among people with CID.

| Variable | Coping scale |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WCC/WCQ | COPE | Brief COPE | CRI | Total number | |

| Type of CID | |||||

| Amputation | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 (4.1%) |

| Cancer | 10 | 13 | 4 | 6 | 33 (33.7%) |

| Cardio | 4 | 5 | 12 | 1 | 22 (22.4%) |

| MS | 12 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 17 (17.3%) |

| SCI | 6 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 13 (13.3%) |

| TBI | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 9 (9.2%) |

| Duration of CID | |||||

| 0–2 months | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 (5.1%) |

| >2 months–2 years | 6 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 18 (18.4%) |

| >2–10 years | 9 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 22 (22.4% |

| >10 years | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 10 (10.2%) |

| Not reported | 13 | 15 | 11 | 4 | 43 (43.9%) |

| Scale version | |||||

| Original | 20 | 23 | 15 | 6 | 64 (65.3%) |

| Modified/partial | 15 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 34 (34.7%) |

| Research Design | |||||

| Cross sectional | 26 | 19 | 21 | 7 | 73 (74.5%) |

| Longitudinala | 9 | 12 | 2 | 2 | 25 (25.5%) |

| Type of outcome used | |||||

| Positive | 5 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 17 (17.3%) |

| Negative | 22 | 15 | 6 | 6 | 49 (50%) |

| Mixedb | 6 | 7 | 10 | 3 | 26 (26.5%) |

| Otherc | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 (6.1%) |

| Direction of association | |||||

| ATC correlated with poor adaptation | 28 | 22 | 21 | 8 | 79 (80.6%) |

| ATC uncorrelated with poor adaptation | 7 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 19 (19.4%) |

| Magnitude of association between ATC and outcomesd | |||||

| r < .10 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 2 | 27 (10.1%) |

| .11 < r < .30 | 16 | 41 | 21 | 1 | 79 (29.5%) |

| .31 < r < .50 | 23 | 34 | 35 | 4 | 96 (35.8%) |

| r > .51 | 8 | 10 | 6 | 1 | 25 (9.3%) |

| β significant | 11 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 26 (9.7%) |

| β nonsignificant | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 (3%) |

| ATC scale’s alpha coefficient valuee | |||||

| α ⩽ .50 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 6 (5.3%) |

| .50 < α ⩽ .70 | 10 | 11 | 6 | 3 | 30 (26.5%) |

| α > .70 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 0 | 29 (25.7%) |

| α unspecified, unreported, or includes multiple values | 20 | 17 | 8 | 3 | 48 (42.5%) |

WCC: Ways of Coping Checklist; WCQ: Ways of Coping Questionnaire; COPE: Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced; CRI: Coping Responses Inventory; CID: chronic illness and disability; MS: multiple sclerosis; SCI: spinal cord injuries; TBI: traumatic brain injuries; ATC: avoidance-type coping.

Of these: T1–T2 (n = 14), T1–T3 (n = 7), T1–T4 (n = 3), and T1–T9 (n = 1).

Includes both negatively and positively valanced outcome measures.

Includes non-traditional, trait-like outcomes such as hope, optimism, self-efficacy, as well as seldom used measures (see “Discussion”).

Many of the studies reported correlations between different ATC scales/measures and several outcomes, yielding a total of 268 coefficient values. Also, several studies reported only β values and their level of significance. Finally seven studies failed to report any qualitative data (see “Results”).

Several of the studies reported more than one ATC measure, yielding a total of 113 coefficient values.

Type and duration of reviewed CIDs

Of the four coping scales reviewed, four were used with people who underwent amputation (4.1% of all CIDs), 33 were employed among cancer survivors (33.7%, with COPE and WCC/WCQ being the most widely used), 22 addressed coping among heart patients (22.4%, led by Brief COPE), 17 were used with MS samples (17.3%, led by WCC/WCQ), 13 studies employed samples of people with SCI (13.3%, roughly evenly distributed among WCC/WCQ, COPE, and Brief COPE measures), and 9 were used among TBI survivors (9.2%, COPE being most prevalent). Duration of CID onset, or diagnosis, was collapsed into five categories, four of which were directly tied to length since onset or diagnosis, and the fifth one encompassed all studies were no duration was reported. Of the 98 reviewed studies five (5.1%) first measured coping with the condition within 2 months since onset (COPE being used in three of these). In 18 (18.4%) studies, first coping measurement (reported as either mean or median) occurred during the time period of 2 months–2 years following CID onset (WCC/WCQ and COPE, each, reported six times in these studies). In 22 (22.4%) studies, measurement of coping (mean or median) was first attempted within 2–10 years following CID onset (9 for WCC/WCQ and 7 for Brief COPE). In 10 (10.2%) additional studies, mean or median duration of CID exceeded 10 years at first coping measurement (half of which were reported for WCC/WCQ). Finally, in 43 of the studies no data were provided on participants’ duration of condition (43.9%). These studies represented mostly samples of people with cancer and heart conditions, where researchers elected to provide, instead, data on condition’s level of severity (stage of disease for cancer patients, and the New York Heart Association (NYHA) cardiac severity level among heart patients).

Research designs and samples of respondents

Researchers relied mostly on cross-sectional research designs (73 of 98, 74.5%) when presenting their findings, with longitudinal research designs distributed as follows: (a) T1–T2 (15.3%); (b) T1–T3 (6.1%); (c) T1–T4 (3.1%); and (d) T1–T96 (a single study). Findings also indicated a differential use of coping scales among the six examined CIDs. For example, whereas coping among MS respondents was explored mainly with the use of the WCC/WCQ measures (70.6% of studies employing respondents with MS), coping among individuals with heart conditions was mostly examined with the Brief COPE (54.5%). For survivors of cancer, two scales were most often adopted, namely, COPE (43.3%) and WCC/WCQ (30.3%). Almost one-half (46.1%) of the studies focusing on SCI survivors employed the WCC/WCQ, while coping among TBI survivors was approached mostly (44.4%) with the use of COPE.

Adherence to scales’ original form

A review of type of coping scales employed further indicated that researchers adopted a rather liberal approach when employing their measures, frequently modifying, abbreviating or, otherwise, tailoring the measure to their own research needs, often offering no clear justification. In the 98 studies reviewed, authors relied on the originally published coping scales 65.3% of the time. Of these, the original (60-item) COPE scale was used 74.2% of the time, while the original CRI (48-item) and Brief COPE (28-item) scales were each used two-thirds of the time. The WCC/WCQ (66- to 68-item) original versions were employed only 57.1% of the time.

Use of outcome measures

Of the 98 studies reviewed, only one-half (49) adopted negatively valanced outcome measures. In total, 17 (17.3%) studies relied exclusively on positively valanced outcome measures, while 26 (26.5%) studies employed both sets of outcome measures. The “other” measures category included merely six (6.1%) studies.

Psychometrics of ATC scales and the strength of their relationships to psychosocial outcomes

Findings concerning the relationships between ATC and psychosocial adaptation to CID indicate that the adoption of ATC strategies is consistently linked to poorer indicators of psychosocial adaptation to CID. More specifically, in the preponderance of the studies reviewed (79 of 98; 80.6%), the anticipated trend was upheld (27 of 34, 79.4% for WCC/WCQ; 22 of 31, 71.9% for COPE; 20 of 22, 91.3% for Brief COPE; and 8 of 9, 88.9% for CRI), while in 19 (19.4%) studies no association between ATC and adaptation was found, or researchers reported either inconsistent or mixed findings. More specifically, a total of 268 correlation coefficients were extracted from the 98 reviewed studies. These represented all reported correlations between the sets of ATC measures/scales (e.g. BD and denial) and outcome measures (e.g. depression and QOL). For longitudinal studies, to reduce the preponderance of available data, median bivariate correlations were computed and used. Findings revealed the following: (a) in 27 (10%) of the studies, correlation magnitudes between ATC and psychosocial adaptation indices were lower than .10 (–.10 < r < .10), and roughly equally distributed between negative and positive values, where COPE (n = 10) and WCC/WCQ (n = 9) were most commonly reported; (b) in 36 cases (13.4%), magnitudes were in the range of .11 < r < .20, with the preponderance of these values (n = 21, 58.3%) reported in studies using the COPE; (c) 43 correlations (16%) yielded values in the range of .21 < r < .30, most of which were associated with COPE (n = 20) and Brief COPE (n = 14); (d) the largest group of correlations (n = 54, 20.1%) were reported in the range of .31 < r < .40, again, led by both Brief COPE (n = 25) and COPE (n = 17); (e) the group of correlations in the range of .41 < r < .50, yielded 42 findings (15.6%), reported mostly for COPE (n = 17), followed by WCC/WCQ (n = 11) and Brief COPE (n = 10); (f) in the range of correlations of .51 < r < . 60, 18 (6.7%) values can be found, and half of these (n = 9) were reported for COPE; and (g) seven correlations in excess of .61 (2.6%) were reported, where WCC/WCQ and Brief COPE, each accounted for three of these. In 34 cases (12.6%) β values were reported, of which 26 were statistically significant, while 8 failed to achieve significance. Finally, seven (2.6%) studies reported only non-quantitative, generalized statements, suggesting only that findings were “significant” or “higher than,” and these were grouped into a separate category. Table 1 provides a truncated version of the above findings.

Finally, reliability coefficients of the various ATC scales were examined. In total, 113 indicators of ATC were reported in the 98 reviewed studies (several of the studies employed more than one ATC indicator). Of these 113 indicators only 30 (26.5%) met the α ⩾ .70 internal reliability criterion typically favored in the psychometric literature. The distribution of the remaining α coefficients was as follows: (a) α < .50, six (5.3%) studies, half of which associated with the CRI; (b) .70 > α ⩾ .50, 30 (26.5%) studies, 11 and 10 of which, were linked to the COPE and WCC/WCQ, respectively; and (c) 46 (42.5%) studies in which α values were not reported at all by the researchers, and these were mostly prevalent among WCC/WCQ users (41.7% of unreported studies), followed by COPE (35.4%), Brief COPE (16.7%), and CRI (6.25%).

Discussion

The findings yielded by this review indicate that reliance upon ATC strategies, among people who sustained CIDs is linked to poorer psychosocial adaptation. As Table 1 illustrates of the 98 articles reviewed, 79 (80.6%) demonstrated a positive association between ATC and indicators of poor adaptation. This association was especially prominent in studies which employed the Brief COPE (90.9%) and CRI (88.9%) measures. The remainder of the discussion section is structured around those conceptual, procedural, and psychometric concerns that undergird the obtained findings and, accordingly, focuses first on conceptual (e.g. theoretical and structural) concerns that underlie the use of ATC in the study of psychosocial adaptation to CID. Second, the discussion examines those procedural (e.g. technical and process-related) issues that undermine several of the reported findings. Third, specific empirical, in this case psychometric (e.g. measurement procedures, (sub)scale reliability, and validity), weaknesses inherent in the employed coping measures are discussed.

Conceptual and structural issues

Inconsistent frameworks for conceptualizing the components of ATC

The theoretical undergirding (e.g. conscious vs unconscious motivation, internal vs external psychological processes, and situation-specific vs trans-situational coping) of what constitutes ATC, its operational definition, and its actual measurement present a highly discrepant picture. Whereas the two COPE scales differentiate among various fine-grain ATC components such a BD, MD, denial, and possibly substance abuse; and the CRI into cognitive avoidance, resignation, seeking alternative rewards, and emotional discharge; the WCQ collapses these and related coping strategies into broader avoidance categories, such as escape-avoidance and distancing. In the CISS (not examined in this article), for example, ATC is perceived in terms of actively seeking to distract oneself through the pursuit of other situations, tasks or social activities, rather than through passive means. Apart from these theoretical–structural conceptualizations, many of the studies, further rely on loosely based empirical findings (or occasionally, on theoretical grounds) derived by the researchers to create their own ATC (sub)scales, including wishful thinking (Moore et al., 1994; Pakenham and Stewart, 1997), detachment (McCabe, 2006; McCabe et al., 2004), denial (Livneh et al., 1999; Murberg et al., 2002; Tallman, 2013), avoidance (McCaul et al., 1999; Noor et al., 2016), distancing (Rochette and Desrosiers, 2002; Zabalegui, 1999), cognitive/behavioral escape/avoidance (Aarstad et al., 2011; Kennedy et al., 2000; Mytko et al., 1996), mental/behavioral/problem disengagement (Park et al., 2008); self-distraction (Schrovers et al., 2011); emotional-focused coping (Pakenham, 1999; Vollman et al., 2007), minimization (Kendall and Terry, 2008), and maladaptive coping (Paukert et al., 2009; Perez-Garcia et al., 2014; Rogan et al., 2013). Clearly, then, the theoretical and operational conceptualizations of ATC create a substantial obstacle in interpreting empirical findings associated with indicators of psychosocial adaptation.

Coping scales are structured differently and present inconsistent directions to respondents

Coping scales often differ in the instructions given to respondents on how to view the presented items (i.e. the encountered stressful event) and the time frames to be considered in responses. Although not restricted to only ATC, items on certain scales are phrased in past tense (WCQ and CRI), while others combine past and present tenses (COPE and Brief COPE). Likewise, scales differ in the specific time frame that respondents are asked to consider, ranging from past week (WCQ), to past 1 year (CRI), and to only “generally” (the COPE). Inherent in the use of differentially used time frames is the conceptual distinction between coping as a state or situationally determined construct (e.g. WCQ) and coping as a trait or a trans-situational construct (e.g. COPE). Scales also differ in terms of verb choice. Whereas some items, and at times parts of scales, are phrased in definitive actions (e.g. I accepted . . ., I worked on . . .), other items are presented in a more tentative or passive phraseology (e.g. I tried to . . ., I got used to . . .). In addition, whereas some scales are phrased in affirmative first-person format (I did . . ., I went . . .; WCQ, COPE), others rely on a question-like, second person scenario (Did you . . .; CRI). Finally, a disparity in structure (total number of content subscales used) and length (total number of items per subscale, ranging from 2 to 16) places disproportional respondent burden (time and energy) on participants, as well as requires scale-specific cognitive and attentive focus. Although, individually, these concerns may not pose a substantial limitation to the empirical foundation of ATC-to-psychosocial adaptation relationship, in combination they are likely to introduce unnecessary random error variance that may significantly affect the validity of these findings.

Procedural and technical issues

Use of a wide range and conceptually diverse psychosocial outcome measures

A wide range of loosely associated and conceptually discrepant outcome measures have been employed in measuring the influence of ATC strategies on psychosocial adaptation to CID. Among the outcomes adopted by CID researchers are some that are positively valanced, such as life satisfaction, well-being, post-traumatic growth, positive affectivity, acceptance, and perceived QOL (Elfstrom et al., 2005; Holland and Holahan, 2003; King et al., 1998; Tallman, 2013; Tuncay and Musabak, 2015). In contrast, other studies have elected to focus on negatively valanced outcome indicators, such as depression, anxiety, anger, psychological distress, negative affectivity, and symptom distress or severity (Arnett et al., 2002; Barinkova and Mesarosova, 2013; Bartmann and Roberto, 1996; Ben-Zur et al., 2000; Bose et al., 2016). Finally, a substantial number of studies preferred to use, as outcomes, more stable personality characteristics such as optimism, hope, neuroticism, helplessness, resilience, self-efficacy, and self-concept (Lynch et al., 2001; Miller et al., 1996; Murberg et al., 2004; Peter et al., 2014; Shen et al., 2004; Strober, 2017; Sumpio et al., 2017; Tan-Kristanto and Kiropoulos, 2015; Tomberg et al., 2005; Trivedi et al., 2009). Research findings, however, have consistently demonstrated that both positively and negatively measured psychological constructs tap different conceptual domains, and are, therefore, largely independent in nature (Diener and Emmons, 1984; Watson et al., 1988). As such, these outcomes are also expected to be differentially predicted by psychological variables, such as coping strategies, including ATC. In one study (Hudek-Knezevic et al., 2002), two derived ATC strategies were positively related to anger, depression and anxiety, among nonhospitalized (but not hospitalized!) cancer survivors. However, following an, multiple regression analysis (MRA), only anger was successfully predicted by both strategies, whereas anxiety and depression were independent of them, thus suggesting that both patterns of relationships, as well as setting (hospital vs community) play a role in determining how ATC is linked to different indicators of negative affectivity. In a sample of heart failure survivors, Burker et al. (2009) examined the relationships among three of COPE’s ATC strategies (i.e. MD, BD, and denial) and various facets of QOL (e.g. role limitations due to emotional problems, vitality, social functioning, psychological distress, and well-being) and found out that these associations present a rather complex, inconsistent and outcome-dependent picture. Finally, findings from a longitudinal study of heart disease survivors (Lowe et al., 2000), indicated that ATC was differentially associated with measures of anxiety, negative affect and positive affect, both in pattern of relationships and across time, again attesting to the complexity of relationships between ATC and psychosocial outcomes.

Use of a wide range of CID-triggered functional limitations, severity levels, and temporal progression

The types of disabling conditions and their associated functional limitations vary immensely in the reported studies, and therefore require the adoption of different coping modalities to minimize daily impact of condition. Medically associated factors, such as level of life-threat, chronicity, and onset of condition, its progress, and presence and level of experienced pain, could also differentially influence the use and adaptability level of ATC. Another concern relates to the unfolding of the medical impact, and therefore the coping strategies adopted, over time. Whereas there is only scarce empirical documentation to suggest that the use of ATC may be associated with better psychosocial adaptation, typically in the earlier stages following the experience of disabling conditions (Kennedy et al., 1995; Pollard and Kennedy, 2007), the bulk of findings suggest that the use of ATC people with CID, is linked, in the long run, to poorer psychosocial adaptation (e.g. Aarstad et al., 2011; Beisland et al., 2014; Carver et al., 1993; Kendall and Terry, 2008; Kennedy et al., 2000; King et al., 1998; Klein et al., 2007; Pakenham, 1999). Furthermore, the extended use of avoidant and denial coping may also worsen prognosis of life-threatening CIDs, such as cancer and heart disease, as well as directly interfere with prescribed medical treatment (Burker et al., 2005; Costanzo et al., 2006; Manne et al., 1994; Murberg et al., 2004). It has been argued that ATC possesses some clinical merit (i.e. associated with positive outcomes) when employed in the context of unmanageable and uncontrolled CIDs, and also relatively early in the adaptation process, where it serves to cushion the impact of traumatic experience. However, it is often linked to poor outcomes when used in the long run or when applied to manageable stressful situations (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984; Livneh and Martz, 2012; Suls and Fletcher, 1985).

Highly discrepant measured durations since CID onset or diagnosis

Duration of medical condition since onset or diagnosis varies appreciably among the various studies reported in the literature (See Table 1). More specifically, whereas in some studies, findings were obtained from participants’ experiences that were reported only several days or weeks following CID onset or diagnosis (Barone and Waters, 2012; Bartmann and Roberto, 1996; Ben-Zur et al., 2001; Bigatti et al., 2012; Bose et al., 2016; Bryant et al., 2000; Buckelew et al., 1990; Hack and Degner, 1999; Kennedy et al., 2012; King et al., 1998; Lowe et al., 2000; Moore et al., 1994; Sumpio et al., 2017; Tan-Kristanto and Kiropoulos, 2015; Terry, 1992), other studies based their findings on coping efforts that were reported many months or even years and decades following the disabling experience (Falgares et al., 2019; Goretti et al., 2009; Grech et al., 2016; Lequerica et al., 2008; Pakenham and Stewart, 1997; Peter et al., 2014). Finally, in many studies, data were averaged across a wide range of years since onset or diagnosis, that spanned up to 25 years among heart patients (King et al., 1998), 35–52 years in people with MS (Lode et al., 2010; O’Brien, 1993; Pakenham, 1999), 37–40 years among SCI survivors (Elfstrom et al., 2005; Lequerica et al., 2008), and 8–30 years among TBI survivors (Moore et al., 1994; Rogan et al., 2013). These extended time durations between the reported CID-triggered onset of stress and the time when (avoidant) coping was formally assessed are, therefore, subject to memory decay and contamination by intervening stressful life events (Gregorio et al., 2014). In addition, it must be recognized that in a large number of studies authors neglected to specify their sample’s condition duration or elected to report only clinical classifications in the form of disease stage or functional status severity (Table 1). It can be argued that the relationships between ATC and psychosocial outcomes, as well as the intricate relationships among coping modalities, changing sociodemographic characteristics, medically based variables, personality attributes, and environmental conditions, are all likely to be drastically altered in the course of a prolonged period of time.

A high degree of domain, content and item contamination exists between ATC and nonadaptive psychosocial outcomes

A substantial overlap is present in both the conceptual underpinnings and item content selected to represent measures of ATC and indicators of psychosocial adaptation, especially those of poor adaptation (e.g. anxiety, depression, and general distress). This item pool overlap invariably results in artificially created and spurious correlations between the two sets of items (i.e. ATC and measures of distress). Overlapping domains include dual references to such symptoms or reactions as: (a) sleep (e.g. “I slept more than usual” (WCQ escape-avoidance) and as an indicator of depression); (b) avoidance of family, friends, and people in general (e.g. “I generally avoided being with people” (WCQ escape-avoidance) and as an indicator of depression); (c) frustration, anger, and upset (e.g. “Take it out on other people when felt angry or depressed” (CRI avoidance/emotional discharge) and as an indicator of psychological distress); (d) resignation, giving up, and fatalistic outlook (e.g. “I just give up trying to reach my goal” (COPE behavioral disengagement) and as an indicator of depression); (e) catastrophizing and anticipating failure (e.g. “expect the worst possible outcome” (CRI avoidance/acceptance or resignation) and as an indicator of depression and anxiety); (f) crying, feeling depressed, and losing hope (e.g. “Did you cry to let your feelings out?” (CRI avoidance/emotional discharge) and as an indicator of depression and emotional distress); and (g) purposeful distraction (e.g. I’ve been . . . going to movies, watching TV . . .” (Brief COPE self-distraction) and as an indicator of denial and resignation). Clearly, the masking of many of these ATC responses as bonafide coping items inflates their association with nonadaptive psychosocial outcomes.

Studies frequently rely on cross-sectional rather than longitudinal research designs

The importance of longitudinal research designs to study the influence of coping strategies on psychosocial adaptation has been consistently stressed in the literature (Lazarus, 2000; Livneh and Martz, 2012; Park, 2010). Yet, most of the reported research relies on less temporally stable cross-sectional designs (Livneh and Martz, 2012; Manne, 2003; Table 1). Indeed, it could be argued that in contrast to longitudinal designs that afford the researcher a dynamic, interactive, and more fluid understanding of the relationships between ATC and psychosocial adaptation, cross-sectional designs offer only a static, time-bound and limited understanding of such relationships. This mere snapshot of the examined association between the two constructs prevents any attempt at drawing causal inferences. Among research efforts that did implement longitudinal designs, when studying ATC of people with cancer, heart diseases, multiple sclerosis, SCI and TBI, are those by Bussell and Naus (2015), Hanson et al. (1993), Kennedy et al. (2012), Kortte et al. (2010), Lode et al. (2010), Park et al. (2008), Rabinowitz and Arnett (2009), Tomberg et al. (2007) and Yang et al. (2008) (all employing a two-time period design: T1 and T2); Kendall and Terry (2008), Lowe et al. (2000), Stanton et al. (2002), and Stanton and Snider (1993) (employing a T1, T2, and T3 design), and Carver et al. (1993), King et al. (1998), and Sherman et al. (2000) (employing a T1, T2, T3, and T4 design). In one study, follow-up measurements extended over of 9-period (T1–T9) 2-year duration (Kennedy et al., 2000). It is of interest that in many of these longitudinal studies, findings indicate that the various facets of ATC relate differentially to indicators of psychosocial adaptation over time. This was evident among cancer survivors (e.g. Sherman et al., 2000), individuals diagnosed with heart failure (e.g. King et al., 1998; Lowe at al., 2000), those with MS (e.g. Aikens et al., 1997), spinal cord injured persons (e.g. Kennedy et al., 2000), and survivors of TBI (e.g. Kendall and Terry, 2008). Furthermore, in these longitudinal designs, which spanned from a few months to several years, no clear trend was established, that is, the temporal trajectories of association between ATC and psychosocial adaptation failed to depict a uniform pattern or suggest any clear clinically discernable trend.

Presence of demand characteristics, recall, social desirability, and self-awareness pitfalls

Although extending beyond limitations reflective merely of items representing ATC and nonadaptive psychosocial indicators, the presence of a wide range of negatively valanced items, nevertheless, poses a major obstacle in interpreting the veracity of ATC—nonadaptive outcomes link. More specifically, since data from measures of coping and psychosocial adaptation are derived almost exclusively by retrospective self-report means, and since these measures require the respondent to “admit” to negative (that is, socially frowned-upon) emotions, cognitive processes, practices, and personal traits, the likelihood of frank responding is greatly compromised. Furthermore, it is likely that throughout the crisis period following the onset or diagnosis of CID, respondents were functioning in “survival mode” style (Manne, 2003), that is, adopting an “automatic” or “reflexive” way of proceeding through life, without ever engaging in any deliberate and thoughtful appraisal of their condition and its probable consequences (Compas et al., 1997; Tennen and Affleck, 2009). Nor were respondents consciously weighing the different options available to them or contemplating existing resources upon which they can draw (Coyne and Gottlieb, 1996). Therefore, any present attempts to recall the remote past and its crisis-related ambience, during questionnaire completion time, are likely to reflect distorted images of that past and cannot be considered accurate representations of coping, including ATC. Finally, social desirability concerns are paramount in these studies, and in particular, for items and content domains that reflect the negative, undesirable nature of one’s thoughts and behaviors, as implied by ATC, as well as by indicators of poor adaptation. In this venue, respondents may be influenced by dominant sociocultural themes that advocate problem resolution, confronting life obstacles, demonstrating self-reliance and personal independence, and, in general, conveying a “fighting spirit” (Coyne and Gottlieb, 1996). To the extent that respondents are unduly influenced by such social pressures to conform to certain implicitly imposed norms, they may forgo any admission of deploying coping modalities that indicate personal weaknesses. In a study with far reaching implications, Krpan et al. (2011) compared coping responses of TBI survivors with a matched control group during a real-world stressful situation. Both groups completed the self-report WOC and a behaviorally based avoidant measure. Results showed that whereas for the control group scores on both measures of coping were positively associated, in the group of TBI survivors no such relationships were observed. The authors concluded, from these findings, that among TBI survivors, real-life measures of avoidant behavior may be more sensitive and accurate than are self-report measures of ATC. Under these circumstances, the accuracy of ATC measurement and the admission to nonadaptive emotions and behaviors must be regarded as suspect at best, if not misleading.

Psychometric and measurement issues

Studies often rely on researcher-generated or unstable factor analytic-derived “subscales” to predict adaptation

Another major obstacle to the reported findings’ veracity is a frequent reliance on presumably theoretically driven, but empirically unsupported, scale composition, or on unstable, sample-specific derived, and therefore ungeneralizable, coping scales or factors. Within the context of coping with CID, this domain spans three independent, but somewhat related, weaknesses. First, in certain studies, researchers derived their ATC scale purely on theoretical grounds or from reliance on findings yielded by previous studies even if these findings are only loosely associated with the present study’s sample composition (Bose et al., 2016; Eisenberg et al., 2012; Gould et al., 2010; Lode et al., 2009; McColl et al., 1995; Sumpio et al., 2017; Tan-Kristanto and Kiropoulos, 2015; Wonghongkul et al., 2000). Second, factor analytic (mostly exploratory FA) procedures used to create coping (including ATC) factors, have often resulted in inconsistent coping structure, with number of scales ranging from (depending on measure used) 2–6 subscales (Bose et al., 2015, 2016; Finset and Andersson, 2000; Kershaw et al., 2004; Nahlen and Saboonchi, 2010; Park et al., 2008; Perez-Garcia et al., 2014; Peter et al., 2014; Tomberg et al., 2007). Finally, within the CID literature, the empirically derived ATC factor(s) or scale(s) demonstrate a widely discrepant picture, with a different composition of both the original subscales included (e.g. wishful thinking, BD, MD, denial, social withdrawal, avoidance, and self-distraction), and the number and type of items extracted from these subscales (Bean et al., 2009; Bennett, 1993; Livneh et al., 1999; Lode et al., 2009; Perez-Garcia et al., 2014; Schrovers et al., 2011; Sumpio et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2008).

Lack of reported psychometric data from present study’s sample

Unreported psychometric data for ATC scales of the researcher-used (CID-derived) samples is a rather problematic and perplexing occurrence among many of the studies (Table 1). In these studies, the authors indicate psychometric (e.g. internal reliability and test–retest reliability) values reported only in the original (mostly non-CID based), scale-constructing, studies or report no values at all (Barone and Waters, 2012; Beisland et al., 2014; Bigatti et al., 2012; Buckelew et al., 1990; Burker et al., 2009; Goretti et al., 2009; Grech et al., 2016; Hanson et al., 1993; Jean et al., 1997, 1999; Keyes et al., 1987; Mohr et al., 1997; Montel and Bungener, 2007; Rochette and Desrosiers, 2002; Sherman et al., 2000; Tomberg et al., 2005; Trivedi et al., 2009; Warren et al., 1991). Under these circumstances, it is impossible to judge the soundness and utility of the reported findings since the statistical procedures typically applied in these outcome studies (e.g. bivariate correlations, multiple regression analyses, and path analyses) rely heavily on the scale’s psychometric soundness, and in the absence of more recent psychometric data, it is impossible to ascertain the empirical merit of these ATC scales and, more generally, the usefulness of the present findings. Furthermore, data on the scales’ temporal consistency (i.e. test–retest reliability) are typically missing from all, but exceedingly small number, of the reported studies (see also, Gregorio et al., 2014). This lack of temporal data renders the reported findings suspect since any changes reported in use of coping are not necessarily a reflection of changes in respondents’ ATC overtime, but might instead indicate fluctuations across time, stemming from the scale’s temporal instability.

Reported internal reliability values are often poor

When internal reliability coefficients, for ATC measures of the present CID-derived sample, are reported, they are, as typically regarded in the psychometric literature, of unacceptable values (Cronbach’s α < .70). Although this concern is prevalent among many studies that adopt coping measures, and not solely ATC, it nevertheless most common among the latter. In several studies (Table 1), coefficients are reported to be at astoundingly low values of .20 and .30 s (Bartmann and Roberto, 1996; Friedman et al., 1992; Hudek-Knezevic et al., 2002; Landreville and Vezina, 1994; Lequerica et al., 2008; Peter et al., 2014; Van der Zee et al., 2000), or below recommended values (.50 s and low .60 s; Barinkova and Mesarosova, 2013; Bennett et al., 1999; Bose et al., 2016; Hack and Degner, 1999, 2004; Kortte et al., 2010; Miller et al., 1996; Schrovers et al., 2011; Sumpio et al., 2017; Tallman, 2013; Tan-Kristanto and Kiropoulos, 2015) . Only a handful of the reported alpha coefficients reached values in the acceptable range of .70–.80, and hardly any indicated alphas that surpassed .80 (Ben-Zur et al., 2000; Danhauer et al., 2009; Dunkel-Schetter et al., 1992; McCabe et al., 2004). Furthermore, no studies were found where inter-item correlations were reported as a viable alternative to the measurement of internal reliability. Despite the frequent misinterpretation of the meaning and required values of Cronbach’s α in the psychometric literature, the reported, unacceptably low, values suggest that in these studies: (a) a high degree of random measurement error is present and/or (b) a single, unidimensional construct is very likely lacking and, therefore, no unique underlying construct (i.e. ATC) is present.

Study limitations

The findings reported in this study must be interpreted with caution because of several limitations. First, a single author conducted all literature searches. Despite careful efforts to methodically search, examine, review, and summarize pertinent findings from all published material, over a 3-year period, it is conceivable that some of the sources were not thoroughly searched or that counting all articles which met inclusion criteria, at each phase of the review, was not seamlessly accurate. Second, only six CIDs were reviewed leaving findings from other medical conditions (e.g. diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and sensory losses) unaccounted for. This limitation obviously restricts any attempt at generalizing the findings to these conditions. Third, only four primary coping measures were included in this review, thus limiting generalization of findings to other and equally important generic ATC measures, and to those constructed purposefully for specific CIDs (e.g. cancer, heart conditions, and MS). Fourth, the review was limited to English-only published journals and, therefore, missed findings published in non-English journals and possibly people representing both ethnically and geographically diverse backgrounds. Also, any published findings obtained from coping measures which are non-English in nature (e.g. Dutch, German, Hebrew, and Spanish) were not included in this review and, therefore, may not reflect the findings reported here. Fifth, no critical appraisal of risk of selection bias (i.e. the file-drawer concern) was attempted, partially due to the fact that the adopted selection criteria in this non-metanalytic review were rather liberal and more inclusive than those pursued in most published strict metanalytic studies. Finally, this systematic review, despite its intended extensiveness, did not strictly adhere to the recommended Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009 checklist (Moher et al., 2009). Although “Methods” section (including the suggested flow diagram) advocated by PRISMA was closely followed, “Results” and “Discussion” sections were structured somewhat differently to address the unique aims of this study and its focus on non-intervention-based, non-experimental assessment.

Recommendations for future research

Future research efforts should address several limitations inherent in this study. First, the findings reported in this review reflect only those yielded by generic coping scales-based ATC measures. A comparison to findings from CID-specific ATC scales is warranted. Second, since this study did not focus on reported effect sizes, future research may benefit from examining whether the existing methodological variations exert influence on the effect sizes of the association between ATC and psychosocial adaptation. Third, in this study, only six (although most extensively researched in the coping literature) CIDs were carefully examined. Investigating the ATC—psychosocial adaptation link among other types of CIDs should help in further elucidation this link. Fourth, the reasons for the differential use of coping scales among the examined typed of CID require further speculation. Are there conceptual or practical reasons as to why some coping measures were more frequently used among certain types of CID or was the observed uneven distribution purely random in nature? Fifth, a more fine-grained analysis of this data, taking into consideration, the influence of sociodemographic (e.g. gender and age) and CID-related (e.g. severity of CID and experienced level of pain) variable should also be undertaken. Sixth, an item-level analysis of ATC scales is recommended, to examine psychometric properties at that level. Indeed, investigating items for their empirical transparency (e.g. is the item a meaningful reflection of a psychosocial avoidant response or merely a camouflaged duplicate of medical symptomatology) and for their predictive utility of psychosocial adaptation is warranted. Seventh, based on the preliminary findings of this scope limited study, a full-scale meta-analysis of the association between ATC and psychosocial adaptation to CID is clearly warranted which also addresses the moderating role played by a number of demographic, psychological, medical, and environmental variables linking use of ATC and adaptation. Finally, more stringent reliability checks throughout the intensive research process of obtaining and analyzing large amounts of data, must be employed. To minimize conscious and unconscious biases, yielded by the use of a single literature, data, and theme extractor, additional and independent researches should be recruited and deployed.

Conclusion

The preponderance of the available body of empirical literature indicates that the deployment of ATC strategies, following the onset or diagnosis of CID, is a robust predictor of poor psychosocial adaptation (Burker et al., 2005; Desmond and MacLachlan, 2006; Penley et al., 2002; Zeidner and Saklofske, 1996). This study’s findings clearly support such a conclusion. Yet, the veracity of these findings must be viewed cautiously in lieu of a number of conceptual, structural, linguistic, procedural, and psychometric limitations, inherent in the majority of these studies, and in particular in their approach to conceptualizing and measuring ATC. In this article, therefore, an attempt was made to first describe, in some detail, the most commonly used coping measures that include ATC (sub)scales (e.g. escape, denial, BD, MD, and wishful thinking), followed by a systematic review-based search and discussion of the most daunting limitations that render interpretation of the findings on the association between ATC and psychosocial adaptation to CID largely suggestive, yet inconclusive at the present time.

These six medical conditions were specified since an earlier attempt at search, using the generic terms of chronic illness and disability yielded an unwieldly number of potential references (over 5000). The rationale behind selecting these CIDs was twofold: (a) focusing only on those conditions that yielded the highest number of “hits” for ATC within the context of adaptation to specific types of CID and (b) including CIDs that represented a wide range of medical facets, such as permanency (e.g. amputation and SCI), life-threat (e.g. cancer and heart conditions), neurological damage (e.g. MS and TBI), compromised functionality/mobility (e.g. SCI and lower limb amputation), and symptom unpredictability (e.g. MS).

Data derived from these two scales, and from an additional coping measure (The Coping Strategies Indicator; Amirkhan, 1990), on the association between ATC and psychosocial adaptation to CID, are available from the author.

WCQ versions that include anywhere from 65 to 68 items have also been reported.

A more elaborate 7-panel structure has been introduced more recently (Moos and Holahan, 2007).

For the Brief COPE Inventory (Carver, 1997) reported internal consistencies are: denial (α = .54), BD (α = .65), and self-distraction (the renamed MD scale; α = .71).

T1 to Tn notation refers to time of measurement since CID onset/diagnosis. For example, T1–T2, indicates initial (T1) measurement post CID onset/diagnosis, followed by a second measurement (T2, first follow-up).

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

*Indicates article is part of the systematic review.

- *Aarstad AK, Beisland E, Osthus AA, et al. (2011) Distress, quality of life, neuroticism, and psychological coping are related in head and neck cancer patients during follow-up. Acta Oncologica 50(3): 390–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RN, Mosher CE, Cohee AA, et al. (2017) Avoidant coping and self-efficacy mediate relationships between perceive social constraints and symptoms among long-term breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 26(7): 982–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Aikens JE, Fischer JS, Namey M, et al. (1997) A replicated prospective investigation of life stress, coping, and depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 20(5): 433–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amirkhan JH. (1990) A factor analytically-derived measure of coping: The Coping Strategies Indicator. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59(5): 1066–1074. [Google Scholar]

- *Arnett PA, Higginson CI, Voss WD, et al. (2002) Relationship between coping, cognitive dysfunction and depression in multiple sclerosis. The Clinical Neuropsychologist 16(3): 341–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Barinkova K, Mesarosova M. (2013) Anger, coping, and quality of life in female cancer patients. Social Behavior and Personality 41(1): 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- *Barone SH, Waters K. (2012) Coping and adaptation in adults living with spinal cord injury. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing 44(5): 271–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bartmann JA, Roberto KA. (1996) Coping strategies of middle-aged and older women who have undergone a mastectomy. The Journal of Applied Gerontology 15(3): 376–386. [Google Scholar]

- *Bean MK, Gibson D, Flattery M, et al. (2009) Psychosocial factors, quality of life, and psychological distress: Ethnic differences in patients with heart failure. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing 24(4): 131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Beisland E, Beisland C, Hjelle KM, et al. (2014) Health-related quality of life, personality and choice of coping are related in renal cell carcinoma patients. Scandinavian Journal of Urology 49(4): 282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Ben-Zur H, Gilbar O, Lev S. (2001) Coping with breast cancer: Patient, spouse, and dyad models. Psychosomatic Medicine 63(1): 32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Ben-Zur H, Rappaport B, Ammar R, et al. (2000) Coping strategies, life style changes, and pessimism after open-heart surgery. Health & Social Work 25(3): 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bennett P, Lowe R, Mayfield T, et al. (1999) Coping, mood and behavior following myocardial infarction: Results of a pilot study. Coronary Health Care 3(4): 192–198. [Google Scholar]

- *Bennett SJ. (1993) Relationships among selected antecedent variables and coping effectiveness in postmyocardial infarction patients. Research in Nursing & Health 16(2): 131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bigatti SM, Steiner JL, Miller KD. (2012) Cognitive appraisals, coping and depressive symptoms in breast cancer patients. Stress and Health 28(5): 355–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billings A, Moos R. (1981) The role of coping responses and social resources in attenuating the stress of life events. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 4(2): 139–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bose CN, Bjorling G, Elfstrom ML, et al. (2015) Assessment of coping strategies and their associations with health-related quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure: The Brief COPE restructured. Cardiology Research 6(2): 239–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bose CN, Elfstrom ML, Bjorling G, et al. (2016) Patterns and the mediating role of avoidant coping style and illness perception on anxiety and depression in patients with chronic heart failure. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 30(4): 704–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bryant RA, Marroszeky JE, Crooks J, et al. (2000) Coping style and post-traumatic stress disorder following severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury 14(2): 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Buckelew SP, Baumstark KE, Frank RG, et al. (1990) Adjustment following spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation Psychology 35(2): 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- *Burker EJ, Evon DM, Losielle MM, et al. (2005) Coping predicts depression and disability in heart transplant candidates. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 59(4): 215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Burker EJ, Madan A, Evon DM, et al. (2009) Educational level, coping, and psychological and physical aspects of quality of life in heart transplant candidates. Clinical Transplantation 23(2): 233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bussell VA, Naus MJ. (2015) A longitudinal investigation of coping and posttraumatic growth in breast cancer survivors. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 28(1): 61–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. (1997) You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 4(3): 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. (2013) Manual for the COPE Inventory: Measurement Inventory Database for the Social Sciences. Available at: www.midss.ie

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. (1982) Control theory: A useful conceptual framework for personality–social, clinical and health psychology. Psychological Bulletin 92(1): 111–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Carver CS, Pozo C, Harris SD, et al. (1993) How coping mediates the effect of optimism on distress: A study of women with early stage breast cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65(2): 375–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. (1989) Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 56(2): 267–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronister JA, Johnson E, Lin CP. (2009) Coping and rehabilitation: Theory, research, and measurement. In: Chan F, da Silva Cardoso E, Chronister JA. (eds) Understanding Psychosocial Adjustment to Chronic Illness and Disability: A Handbook for Evidence-Based Practitioners in Rehabilitation. New York: Springer, pp. 111–148. [Google Scholar]

- Classen C, Koopman C, Angell K, et al. (1996) Coping styles associated with psychological adjustment to advanced breast cancer. Health Psychology 15(6): 434–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor J, Osowiecki D, et al. (1997) Effortful and involuntary responses to stress: Implications for coping with chronic stress. In: Gottlieb BH. (ed.) Coping with Chronic Stress. New York: Plenum Press, pp. 105–130. [Google Scholar]

- *Costanzo ES, Lutgendorf SK, Rothrock NE, et al. (2006) Coping and quality of life among women extensively treated for gynecologic cancer. Psycho-Oncology 15(2): 132–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Couture M, Desrosiers J, Caron CD. (2012) Coping with a lower limb amputation due to vascular disease in the hospital, rehabilitation, and home setting. ISRN Rehabilitation 2012: Article 179878. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC, Gottlieb BH. (1996) The measurement of coping by checklist. Journal of Personality 64(4): 959–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Danhauer SC, Crawford SL, Farmer DF, et al. (2009) A longitudinal investigation of coping strategies and quality of life among younger women with breast cancer. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 32(4): 371–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond DM, MacLachlan M. (2006) Coping strategies as predictors of psychosocial adaptation in a sample of elderly veterans with acquired lower limb amputations. Social Science & Medicine 62(1): 208–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA. (1984) The independence of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 47(5): 1105–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duangdao KM, Roesch SC. (2008) Coping with diabetes in adulthood: A meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 31(4): 291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Dunkel-Schetter C, Feinstein LG, Taylor SE, et al. (1992) Patterns of coping with cancer. Health Psychology 11(2): 79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Eisenberg SA, Shen BJ, Schwarz ER, et al. (2012) Avoidant coping moderates the association between anxiety and patient-rated physical functioning in heart failure patients. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 35(3): 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Elfstrom ML, Kreuter M, Persson LO, et al. (2005) General and condition-specific measures of coping strategies in persons with spinal cord lesion. Psychology, Health & Medicine 10(3): 231–242. [Google Scholar]

- Endler NS, Parker JD. (1999) Manual for the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS) (2nd edn). North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Falgares G, Lo Gioco A, Verrocchio MC, et al. (2019) Anxiety and depression among adult amputees: The role of attachment insecurity, coping strategies and social support. Psychology, Health & Medicine 24(3): 281–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Finset A, Andersson S. (2000) Coping strategies in patients with acquired brain injury: Relationships between coping, apathy, depression and lesion location. Brain Injury 14(10): 887–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. (1980) An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 21(3): 219–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. (1988) Manual for the Ways of Coping Questionnaire. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, et al. (1986) The dynamics of a stressful encounter. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 50(5): 992–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Friedman LC, Nelson DV, Baer PE, et al. (1992) The relationship of dispositional optimism, daily life stress, and domestic environment to coping methods used by cancer patients. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 15(2): 127–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Goretti B, Portaccio E, Zipolli V, et al. (2009) Coping strategies, psychological variables and their relationship with quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Neurological Science 30(1): 15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Gould RV, Brown SL, Bramwell R. (2010) Psychological adjustment to gynaecological cancer: Patients’ illness representations, coping strategies and mood disturbance. Psychology and Health 25(5): 633–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Grech LB, Kiropoulos LA, Kirby KM, et al. (2016) Coping mediates and moderates the relationship between executive functions and psychological adjustment in multiple sclerosis. Neuropsychology 30(3): 361–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorio GW, Brands I, Stapert S, et al. (2014) Assessments of coping after acquired brain injury: A systematic review of instrument conceptualization, feasibility, and psychometric properties. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 29(3): E30–E42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hack TF, Degner LF. (1999) Coping with breast cancer: A cluster analytic approach. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 54(3): 185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hack TF, Degner LF. (2004) Coping responses following breast cancer diagnosis predict psychological adjustment three years later. Psycho-Oncology 13(4): 235–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagger MS, Orbell S. (2003) A meta-analytic review of the common-sense model of illness representations. Psychology and Health 18(2): 141–184. [Google Scholar]

- *Hanson S, Buckelew SP, Hewett J, et al. (1993) The relationship between coping and adjustment after spinal cord injury: A 5-year follow-up study. Rehabilitation Psychology 38(1): 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH. (1987) Personal and contextual determinants of coping strategies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 52(5): 946–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Holland KD, Holahan CK. (2003) The relation of social support and coping to positive adaptation to breast cancer. Psychology and Health 18(1): 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- *Hudek-Knezevic J, Kardum I, Pahljina R. (2002) Relations among social support, coping, and negative affect in hospitalized and nonhospitalized cancer patients. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 20(2): 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Iturralde E, Weissberg-Benchell J, Hood KK. (2017) Avoidant coping and diabetes-related distress: Pathways to adolescents’ type 1 diabetes outcomes. Health Psychology 36(3): 236–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *January AM, Zebracki K, Chlan KM, et al. (2015) Understanding post-traumatic growth following pediatric-onset spinal cord injury: The critical role of coping strategies for facilitating positive psychological outcomes. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 57(12): 1143–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Jean VM, Beatty WW, Paul RH, et al. (1997) Coping with general and disease-related stressors by patients with multiple sclerosis: Relationships to psychological distress. Multiple Sclerosis 3(3): 191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Jean VM, Paul RH, Beatty WW. (1999) Psychological and neuropsychological predictors of coping patterns by patients with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Clinical Psychology 55(1): 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T. (2015) Frequently used coping scales: A meta-analysis. Stress Health 31: 315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kendall E, Terry DJ. (2008) Understanding adjustment following traumatic brain injury: Is the goodness-of-fit coping hypothesis useful? Social Science & Medicine 67(8): 1217–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kennedy P, Lowe R, Grey N, et al. (1995) Traumatic spinal cord injury and psychological impact: A cross-sectional analysis of coping strategies. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 34(4): 627–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kennedy P, Lude P, Elfstrom ML, et al. (2012) Appraisals, coping and adjustment pre and post SCI rehabilitation: A 2-year follow-up study. Spinal Cord 50: 112–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kennedy P, Marsh N, Lowe R, et al. (2000) A longitudinal analysis of psychological impact and coping strategies following spinal cord injury. British Journal of Health Psychology 5(2): 157–172. [Google Scholar]

- *Kershaw T, Northouse L, Kritpracha C, et al. (2004) Coping strategies and quality of life in women with advanced breast cancer and their family caregivers. Psychology and Health 19(2): 139–155. [Google Scholar]

- *Keyes K, Bisno B, Richardson J, et al. (1987) Age differences in coping, behavioral dysfunction and depression following colostomy surgery. The Gerontologist 27(2): 182–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *King KB, Rowe MA, Kimble LP, et al. (1998) Optimism, coping, and long-term recovery from coronary artery surgery in women. Research in Nursing & Health 21(1): 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Klein DM, Turvey CL, Pies CJ. (2007) Relationship of coping styles with quality of life and depressive symptoms in older heart failure patients. Journal of Aging and Health 19(1): 22–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kortte KB, Gorman P, Gilbert M, et al. (2010) Positive psychological variables in the prediction of life satisfaction after spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation Psychology 55(1): 40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]