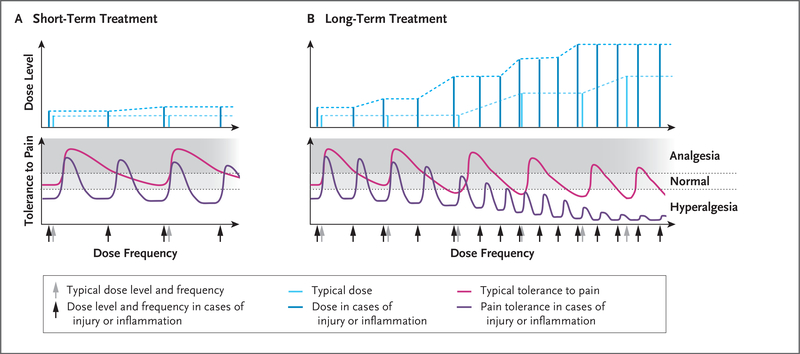

Figure 4. Short-Term and Long-Term Opioid Therapy and Effects of Inflammation or Injury on Pain Threshold.

In Panel A, short-term opioid administration (light blue) provides sufficient analgesia with no or minimal opioid tolerance (pink). In cases of inflammation or injury, as compared with uninjured states, the analgesic potency of the opioid (i.e., the threshold for pain) is decreased, resulting in hyperalgesia; short-term administration of higher doses (dark blue) provides sufficient analgesia but for a shorter duration (purple), requiring more frequent doses (dark blue). Panel B shows that in an uninjured patient with long-term exposure to opioids, the analgesic potency decreases (pink) and the duration of opioid-induced analgesia also decreases with each dose, requiring an increase in dose frequency. Long-term opioid administration will result in induction of antinociceptive mechanisms, resulting in hyperalgesia; even higher doses of opioids (light blue) do not restore complete analgesia (pink). During opioid-induced hyperalgesia in an injured patient, exaggerated pain sensitivity occurs at the injured and uninjured areas. Any cause of systemic inflammation or neuroinflammation (e.g., infection, cancer, diabetes, stress, or chemotherapy) decreases the analgesic potency and the duration of analgesic effects and leads to earlier development of opioid-induced hyperalgesia; even high doses (dark blue) result in minimal analgesia (purple) because of decreased analgesic potency.